Lichtenstein's Magnificent Crystalware and Shiny Fruit

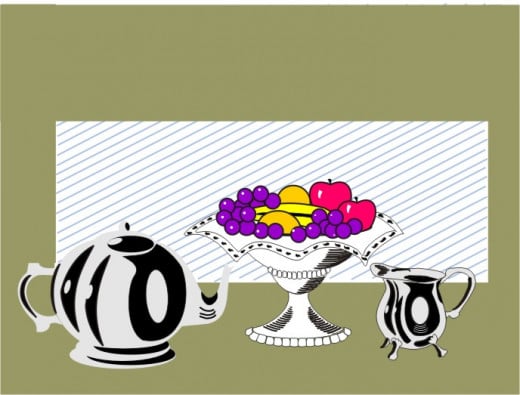

The Final Picture

History of the Still Life

The still life is a genre of painting that depicts inanimate objects, vases filled with flowers and bowls of fruit, carafes of wine and plates of food, books and jewellery, musical instruments, rich fabrics and so on, in intriguing ways. Still lifes have been found on the walls of the excavated Pompeii and other Roman villas, which indicates the probable age of the genre. It lay dormant in the west for the thousand years between the fall of the Roman empire and the early years of the Italian Renaissance. In 1504, Leonardo da Vinci painted The Last Supper, the fresco of Christ and his Apostles seated around a table laid with food and wine. One century later, Caravaggio painted the Supper at Emmaus, (1601, National Gallery, London), in which Christ and his Apostles sit around a table laden with fruit and other foods. However, the later artist brought the still life into a new dimension, making the food glow with almost Cabbalistic significance in the eerie light that surrounds the human and supernatural subjects. This painting seemed to mark a new lease of life, indeed, a golden age for the still life. The aim of the genre was not realism or even beauty. The fruit in basket of the Caravaggio painting is over-ripe, and seems about to fall off the table and into the lap of the viewer. The genre attained true popularity by the middle of the seventeenth century when Dutch artists like Willem Kalf (1619-1693) were painting vases of flowers and scenes of domestic luxury, with fruit, wine and lobsters in silver dishes and crystal goblets. Again, the aim of the genre was not always luxury or beauty. Indeed, the still lifes of Jan van Huysum (1682-1749) seem quite sinister. His humungous earthenware vases bore flowers that were never in season together – no hothouses in the seventeenth century. At this time in history, Holland saw the triumph of the free market and secularism over the intense religiosity of southern Europe. However, wise artists in the north of Europe noted that secular “freedom” came with a price. In time, all temporal things pass away and the consumer luxury so sought after in this world would be of no use in the next.

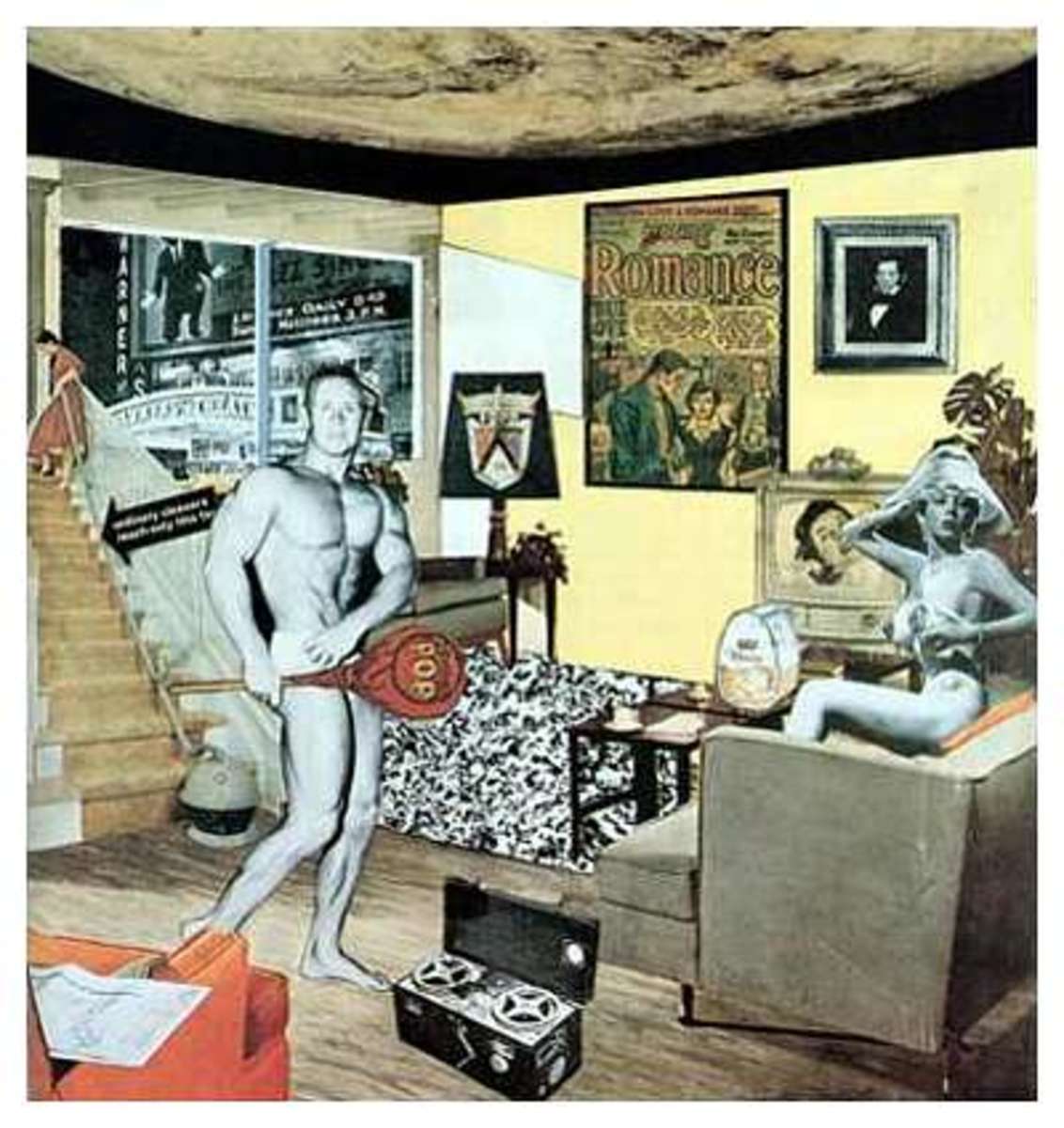

The genre faded from view for several decades and then regained popularity in the nineteenth century, when impressionist artists like Paul Cezanne painted bowls of fruit alongside other domestic objects; The Black Marble Clock (1869-71). Painters like Georges Braques and Juan Gris made “cubist” still lifes while later artists like Giorgio Morandi seemed almost to send up the genre with numerous images of groups of empty pots and vases, for example, his Natura Morta (1956).

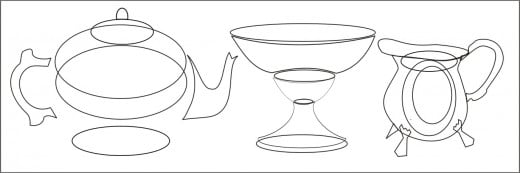

The Outlines

Getting Started

It was only a matter of time before I attempted to paint my own still life masterpiece and I turned to the masters for inspiration. Of course, all my efforts to be another Cezanne or Morandi ended in the waste bin, a stack of ruined drawing boards and a sea of wasted paint. Turning to computer software and my favourite absent teacher, Ray Lichtenstein, was a no-brainer. Since pop art grew from the consumer culture of the twentieth century, it was inevitable that Lichtenstein was going to create his own version of the still life. In images like Still Life with Crystal Bowl (1973), he captures the essence of brightly-coloured, shiny pieces of fruit nestling in a crystal dish, but using his own definitive drawing schema rather than the layers of dense oil paint evoking light and shade that were employed by the masters. It was time to investigate how he did it.

My first step, as always, was to make a rough sketch of the image I wanted. I decided on Lichtenstein’s crystal bowl of fruit, nestling between a silver teapot and a silver jug of milk. Drawing these items of tableware is surprisingly easy using computer software. Simply reduce them to “ovals” around which you draw the basic outlines.

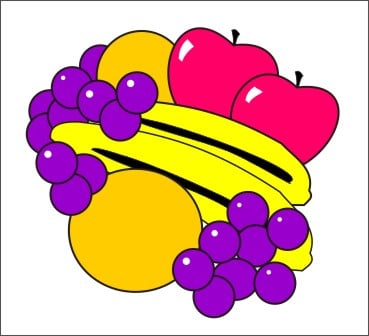

The Fruit

Growing the Fruit

The fruit is the simplest component of the image, and I decided to copy Lichtenstein’s schema directly. When creating your fruit, remember to outline each piece in his characteristic black lines, not too difficult when using computer drawing software. Also, do not make the “round” fruits, like oranges and grapes, exact spheres since these shapes are extremely rare in the natural world. Squishing them into more realistic shapes is a piece of cake when drawing the shapes with the ellipse tool. Decide where you want the light to originate from and add small white patches on individual fruits. This light source will be relevant when finishing the silver and glassware. Remember that “matt” fruits like oranges and bananas do not shine. With the fruit in order, I was ready to tackle the silverware.

Making Progress

On Reflections

Depicting glass and silverware is a little more difficult; a craft that artists like Willem Kalb dedicated his lifetime to perfecting. I observed carefully how Lichtenstein built up reflections on his own surfaces. When trying to create gleaming silver and winking glass, remember that these materials reflect shade as well as light. Also, reflective surfaces in the same surroundings are bound to reflect similar patterns. One feature of computer drawing software is the ease with which the artist can copy a pattern on one surface and transfer it directly to another. When transferring reflective patterns from the teapot to the jug – or vice versa – remember to modify them in accordance with the planes of the new surface. Do not forget that handles and spouts also cast shadows. I built the top and lid of the teapot from a series of ellipses.

Creating mouldings around the perimeter and base of the fruit bowl proved a challenge. However, I managed to put two rows of beading in place, plus little reliefs along the upper edge. I created shadows with rows of curved hatchings along the base and sides.

Finally....

No Lichtenstein image is complete without the background and I decided on a panel of sky-blue hatchings, the making of which I describe in my feature, Draw Like Lichtenstein Using Computer Graphic Software. Finally, I placed the entire arrangement on a surface of dark green, a colour not already in the image. Already, I am twitching to move my “still life” skills to the next level, and work at them until I create an entire pictorial banquet, several courses complete with knives, forks, tureens and cruet sets. This effort will be fodder for future features, of course.

Sources

Lichtenstein Posters by Jurgen Doring and Claus van der Osten, Prestel Publishing

The National Gallery Companion Guide by Erika Langmuir, National Gallery Publications, 1974