Making Buddhas: Tibetan Silk Applique Thangkas

A unique Tibetan textile art

This lens will introduce the rare and precious art of Tibetan applique thangkas, explain its history and techniques, and encourage further research into this little-known sacred art form.

Sacred and inspiring Buddhist images rendered in precious silk satins and brocades. Stitched with a special blend of patchwork, appliqué and embroidery techniques unique to the Himalayan region. These artworks are a rare form of thangka.

What is a Thangka?

Thangkas are religious pictorial scrolls, an important artistic form in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

Their non-rigid, rollable shape makes them easily portable (relatively easily, as we'll find when we look at the giant thangkas that require large teams of people to carry). This portability makes thangkas easy to transport and store - essential qualities in a semi-nomadic culture whose religious practices involve a wide array of meditative, instructional, and ritual practices.

The pictures on thangkas usually depict idealized figures which symbolize the expansive qualities of enlightened mind, such as wisdom, compassion, energy, and fearlessness. Some thangkas also illustrate scenes from the life of the Buddha, portraits of respected lamas, iconographic explanations of our experience as living beings, or occasionally even historic events or locations.

Within the context of Tibetan Buddhist culture, these pictorial scrolls serve a variety of purposes:

* They are teaching tools. The wheel of life, for example, is like a blackboard diagram (or a PowerPoint presentation) which can support a Buddhist teacher in explaining our entanglement in the cycle of craving and suffering -- the cycle of birth, aging, illness, death, and rebirth.

* They are objects of veneration and focal points for offering and devotion. Once consecrated, it is believed that the spiritual essence enters into the cloth and outlined forms. Eleanor Olson, in her 1950 article on Tibetan appliqué work, wrote that "the great value of the hangings, as of all Tibetan religious arts, lies in their capacity to evoke a divine presence and to lift the consciousness of the worshiper above the plane of worldly existence." I would say that these works of art can provide the energy and inspiration for practitioners become free of the mental bonds that normally limit and blind them.

* They are supports for forms of meditation involving visualization. In this case, the practitioner does not meditate while gazing upon the thangka but uses the image as a model for his own mental generation of the form and its qualities.

Every aspect of the image - the colors, implements, garments, and gestures -- conveys meaning, and together they communicate the meaning of entire religious texts. The sacred figures are drawn to scripturally defined proportions and display the 32 major and 80 minor marks of an enlightened being. Though not visible to the unawakened, these marks and symbols convey the harmony and serenity of enlightened mind and can generate the aspiration for awakening.

Types of Thangkas

Technically, thangkas are constructed in a variety of materials and methods. The major types of thangkas include the following:

* Painted - the most plentiful and probably the oldest tradition

* Embroidered - produced in China from at least as early as the 13th century

* Tapestry - the Chinese 'cut silk' technique known as kesi or k'ossu

* Stitched Appliqué -- the subject of this article

* Glued appliqué -- a technique which seems to have originated in Eastern Tibet

These days in Tibetan markets, one also finds inexpensive machine-woven images or prints of paintings framed in brocade.

History of Tibetan Painting

An examination of the history of stitched appliqué thangka begins with the history of painting in Tibet, as well as with an understanding of the general role of appliqué in Tibetan culture. It then moves into the complex relationships of cultural exchange among various Asian cultures in the 12th to 15th centuries and beyond.

Art seems to have been integral to the development of Buddhist culture in Tibet. Many great religious masters from the 12th century on were also artists, and most Tibetans known to have painted between the 12th and 15th centuries are known only because they were otherwise famous as religious masters.

The field of art and craftsmanship, which emphasized schema for proportioning sacred images, was one of the five major fields of study of Mahayana scholars. Even non-scholarly masters were knowledgeable about art because it played such an integral part in Buddhist ritual, life, and architecture.

Later, thangka painting became more of a craftsman profession, carried out by laypeople, rather than by lamas or yogis in meditative states. But the work itself, even if not a formal meditation, is a kind of virtuous practice – honoring the deity and bringing it into physical form for others' benefit, working with devotion in service of the donor, the practitioner, and the deity.

Early Tibetan painting styles were primarily influenced by Indian and Nepali -- particularly Newari -- styles. The mid-15th century marks the beginning of what's recognized as a truly Tibetan style of painting; Menla Dhondup, whose style became known as Menri, moved away from the Newari-influenced solid-color (often red and orange) backgrounds filled with decorative patterns toward simplified Chinese-style landscapes dominated by blues and greens.

The imagery in Tibetan thangkas displays a blend of Chinese and Indian influences with characteristically Tibetan elements. Olson, for example, cites the skimpy, flowing, draped garments of the goddesses and tantric deities – attire completely alien to Tibetan culture and climate – as evidence of the Indo-Nepalese influence. On the other hand, scenic and decorative details are often of Chinese origin. Uniquely Tibetan design elements are few, but the “wild vigor and the intensity of religious feeling which often infuse even the traditional imported forms are unmistakably Tibetan,” she notes.

Around the same time Menla Dhondup was developing his style, if not a bit earlier, we find the first accounts of large appliqué thangkas being made at Gyantse. Menla Dhondup himself directed the creation of a 28x19 meter cloth thangka of Buddha Shakyamuni at Tashilunpo in 1468 and a smaller thangka of Tara in 1469. And his son sketched a Buddha figure for a large brocade thangka around 1506.

Appliqué in Tibetan culture

Appliqué is the most characteristic and refined textile work of Tibet. The most impressive examples of this indigenous craftsmanship were the tents and awnings used by monks and laypeople at weeks-long religious festivals, picnics, and other gatherings. One can easily imagine how the colorful decorations enlivened the stark landscape and supported the revelers in their gleeful celebrations. Appliqué also embellished ritual dance costumes and ceremonial garments, saddle blankets and throne covers.

Cultural ping-pong as Fabric Thangkas evolve

Understanding the development of fabric thangkas requires delving into the complex commercial, political, and religious relationships between the Tibetan, Chinese, Tangut, and Mongolian states through several historical periods. My own knowledge of these cultures and their interrelationships is quite limited, but I will attempt here to share with you the skeleton of understanding I have gained through reading the few articles that have been written on the subject by historians of Tibetan art. Please forgive me if I don't provide precise dates and chronology. I will develop this section further as I learn more.

As already noted, Tibetan paintings display a blend of Chinese and Indian influences with characteristically Tibetan elements. Such influences and, more importantly, interactions extended their effect to the development of textile art as well.

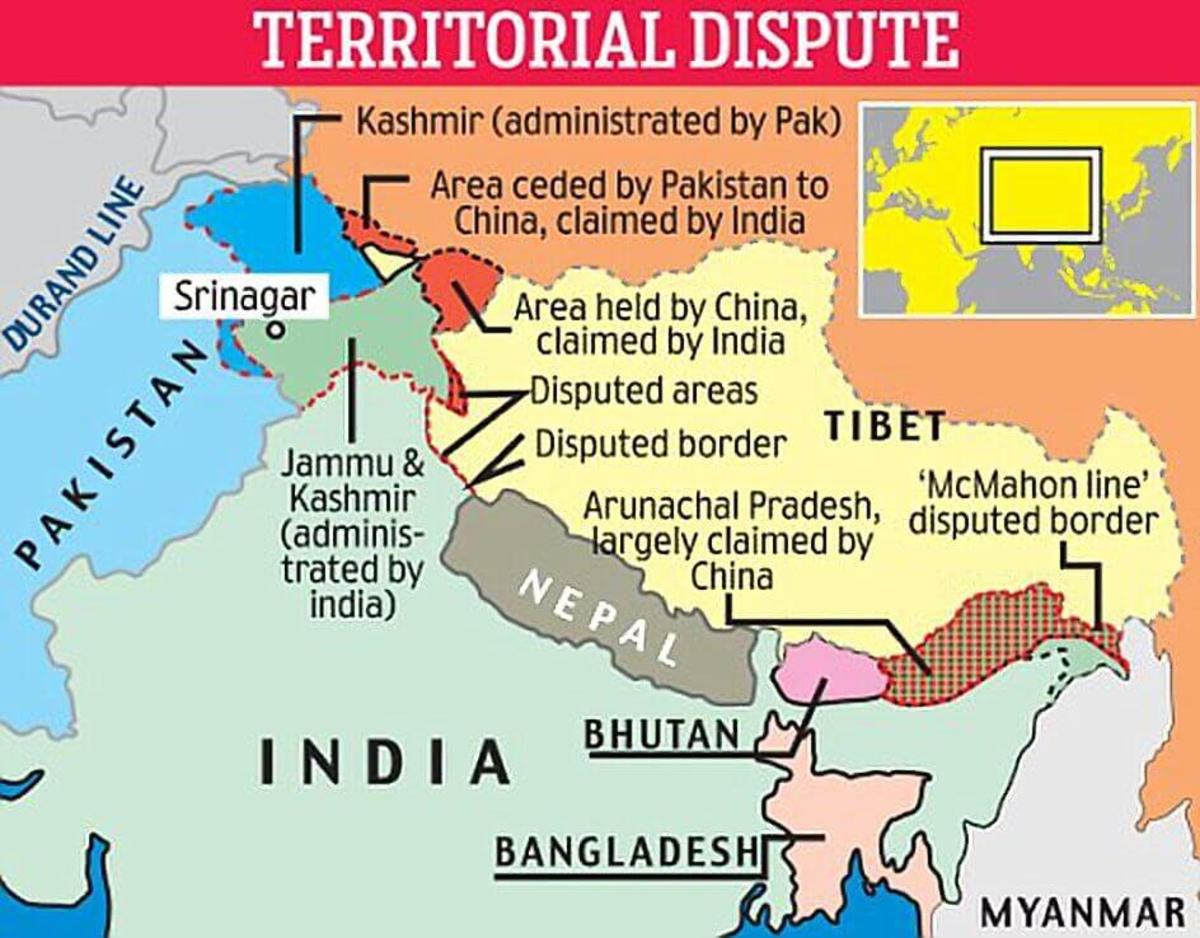

Over the centuries, power in central and eastern Asia changed hands many times. At times the Mongolians held sway over the whole region. Other times, the Chinese or Manchurians held control, and from 982-1227 the Tangut empire was an important force in northwestern China - between Tibet, China, and Mongolia. During several periods, the nation which held temporal power looked to Tibetan lamas for religious guidance and blessings.

Chinese silk played an important role in managing and expressing these relationships. The only indigenous weaving materials in Tibet are wool and yak hair, which are used in the production of clothing, shoes, and nomad tents. Silk came into Tibet as imperial tribute and commercial trade from at least as early as the Tang Dynasty (618-906). A sino-Tibetan treaty of circa 760 records an annual tribute of fifty thousand 'pieces' of silk from the Chinese emperor to the Tibetan court at Lhasa. (Valrae Reynolds, May 1995)

Silk was used as a currency. The price of a horse, for example, is recorded as having been anywhere from twenty to forty bolts of silk, depending on the quality of the horse and the time period. (Valrae Reynolds , May 1995 and April 1997). An exhibition of textiles at The Cleveland and Metropolitan Museums of Art in 1997-1998 was titled "When Silk was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles." The title clearly recognizes the monetary role that silk played and the great value it had.

The Tanguts may have acted as intermediaries between Tibet and China, continuing trade after the collapse of the Tibetan empire in the 9th century (Valrae Reynolds, April 1997) and building strong relationships with Tibet's religious teachers.

In an article on patronage and religious practice in China and Tibet, Valrae Reynolds describes the flourishing of artistic activity in the 11th to 13th centuries as religious teachers founded monasteries with the support of "princely" families. From documents of this period, it emerges that "one of the popular ways to gain religious merit was to donate fine silk for the use of an esteemed teacher of a Buddhist monastery." In this way - through tribute, commerce, and investment -- satins, damasks, and brocades patterned in gold, silver, and a multitude of colors filled the treasuries of Tibet.

When the Mongols took over, consolidating control of all of China after 1279, they adopted many aspects of the destroyed Tangut court's religious connection with Tibetan lamas - giving lamas great power over religious and cultural affairs and promoting artistic ventures incorporating Tibetan Buddhist themes and styles.

The use of silk to create fabric images grew out of these Tangut-Mongol-Tibetan-Chinese interconnections. At some point, copies of Tibetan Buddhist paintings began to be produced using the Chinese textile techniques of embroidery, tapestry (kesi) and brocade.

Valrae Reynolds of the Newark Museum notes that these silken images held "greater cachet than the paintings they were copied from... infinitely more prestigious than the painted 'originals'."

Michael Henss explains that these "pictorial embroideries, tapestries, and brocades fall in between established art historical domains in two ways: they cannot be classified as paintings, nor are they textiles in the usual sense; Chinese by technique and origin, but Tibetan by subject and composition, presented by the imperial court to Tibetan religious officials and visitors, to their monastic enclaves in China and monasteries in Tibet, they did not attract academic interest in the field of Chinese art history or - until a few years ago - in the field of Tibetan Buddhist art." He also asserts that "There are good reasons to regard the multinational Buddhist Tangut state of Xixia (c.982-1227) as the production centre of the earliest Lamaist woven images of around the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries..." (Michael Henss, Nov 1997)

Fabric Images are Produced in Tibet itself

The prestige of fabric images in Tibet started with the imported Chinese textile artworks based on exported Tibetan paintings. At the same time, from the late Yuan period (1279-1368) through the early Ming and into beginning of 15th century when Buddhism was in imperial favor and Tibetan religious leaders had great influence, the Chinese were commissioning a great number of paintings from Tibet. Michael Henss writes that "From the historical background, the regular flow of Tibetan art to China and Chinese art to Tibet between the late thirteenth and the late fifteenth centuries seems still to be underestimated."

At some point, Tibetans were inspired to create their own fabric thangkas using their native appliqué techniques.

Henss points out, "Whereas all tapestry, embroidery, and brocade thangkas were made in China, the giant silk appliqués which came into use for outdoor ceremonies perhaps as early as the fourteenth century, obviously under the influence of such large Chinese banners as those still existing in the Jokhang, are made in a genuinely Tibetan style.

I must admit that I'm still a bit confused about the chronology of the trading and development of the interconnected art forms during the 13th to 15th centuries. I clearly have more to learn, and there is also a need for further research in this area. Valrae Reynolds, in an article examining the Sino-Tibetan appliqué thangka of Tsong khapa in the Newark Museum's collection, writes, "The historical evolution of appliqué techniques prior to the fifteenth century and the relationship between Chinese, Central Asian, and Tibetan appliqué production both need to be examined as the three areas certainly influenced each other over a very long period."

Imperial patronage of the Tibetan monasteries diminished in the second half of the fifteenth century resulting in a decline in Chinese production of Tibeto-Buddhist silk images. This seems to have coincided with the development of the Tibetans' own form of silk image production - appliqué thangkas. So it seems that the Tibetans were inspired by the Chinese textile copies of their paintings to begin creating their own textile versions.

It's not completely clear from my reading of this history whether creative inspiration or economic necessity was the primary motivating factor but Tibet gradually became its own manufacturing centre for textile thangkas, mainly in the appliqué tradition. This production increased and spread throughout the region particularly in the later seventeenth and eighteenth century. In this later period, appliqué thangkas were produced not only in Tibet, but also in Mongolia, Bhutan, and Ladakh.

The Sunning of the Buddha

Compared with painting, textile in general and appliqué in particular is better suited to large works. The fabric is supple and can be carried, rolled, and otherwise manipulated without cracking or creasing. The giant images which could be created with appliqué permitted the development of festive, ritual viewings of these great thangkas. Thousands of people could (and still can in limited locations) witness the annual or biannual (or even less frequent) “sunning” of the Buddha. Monastery walls and hillsides provide support for hundred-foot-high Buddhas. Enormous blessings are believed to be gained by viewing these monumental images, and one can certainly imagine that the awesome experience of grandeur would, in itself, be enormously inspiring.

Terminology - What to Call it

The lack of clear terminology to describe this artwork can be a source of confusion. Though no weaving is involved in the creation of these thangkas, they have been referred to as Tibetan tapestries. In fact, Eleanor Olson, in her 1950 article, recounts the visit of a Tibetan trade mission to the US led by Tsepon W.D. Shakabpa in 1948 in which “tapestries” were listed by the mission as among the products Tibet hoped to export to the US. These “tapestries” were Tibetan appliqués, not Chines kesi works.

People often ask me, “What is the name of the artwork you do? What is it called?” In Tibetan, it is known as gos sku which means fabric image, or gos thang which can be translated as something like “fabric pictorial scroll.”

I have long objected to the use of the term “appliqué” to describe this art form. My objection stemmed from the fact that , though some parts of the scenery are applied to the ground or sky, there is generally no base cloth to which pieces of the image are applied. Instead, images are pieced in a kind of patchwork where adjacent pieces of fabric are united, not by normal seams, but by an overlapping of edges and by the repeated couching of outlining cords.

Recently, however, I have started to use the term “appliqué” in order to be understood, since it is the term of consensus in the field, and because at least one expert in the sewing and quilting world told me that the term could be applied to any work in which one piece is laid on top of another, even if that “on top” is only a slight overlap and not a true applying of a smaller piece onto a larger ground. I'm not completely convinced but, in order to participate more fully in a conversation in which the term “appliqué” is generally used, I have decided to be flexible in using it myself.

Technique - How are they Constructed?

I will briefly describe here the technique extant today among Tibetans in India and Nepal. This is the technique which was taught to me by T.G. Dorjee Wangdu and Tenzin Gyaltsen and which was taught to them by their teachers from Tibet, including the former Namsa Chenmo (personal tailor to the Dalai Lamas), Gyeten Namgyal.

The images are a mosaic or patchwork of silk pieces outlined, cut, and arranged like a jigsaw puzzle, using a drawing as a guide.

To begin the process, an artist makes a line drawing of the figure on cloth or paper. Proportional conventions written in scripture and passed down for centuries guide the artist in drawing the sacred figures of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Adherence to these proportions is believed to be important for the spiritual value and efficacy of the image. But just as is the case with thangka paintings, this does not imply that all thangkas look alike no matter who produces them. The proportions are a context in which to create an original drawing of the figure. They function as guides to the anatomy of sacred beings, allowing an artist to bring his or her own vision of the Buddha forth while maintaining integrity with textual descriptions. The cloth or paper on which this drawing is made does not become part of the finished piece. Rather, it is used as a template or map on the basis of which to build a picture out of silk.

Each distinctly colored area of the image is formed by a separate piece of colored silk. As explained in the historical sections above, in the beginning the silk satins, damasks, and brocades came from China. Later, Russian and Indian brocades were also used. Now, Tibetan artists in exile in India and Nepal use silk materials handwoven in Varanasi, India.

Individual portions of the drawing are copied to the fabric with the help of tracing papers or other transfer methods.

The artist wraps horsehair with silk thread to create colored cords and then couches those cords to the fabric surface along the drawn lines. Couching is a sewing technique whereby a cord or thick thread is fastened to the surface of a cloth with another thread. In this case, the thread used to fasten the cord is the same as the thread used to wrap the horsehair. This results in invisible stitches which blend into the colored cord. As all the outlines and contours of the drawing are defined by these cords, the picture takes on a textured, three-dimensional quality.

The artist cuts the pieces out around the cords and turns the edges under, so that a horsehair cord rests at the edge of each piece forming a raised outline. Then, using the line drawing as a guide for the assembly, the artist places the pieces in their relative positions and glues them together by slightly overlapping adjacent pieces. He or she then carefully hand stitches the pieces together.

Certain small features such as eyes, mouths, and fingernails are embroidered. The eyes -- considered to be the most difficult aspect of the work and traditionally the last skill taught to students after years of apprenticeship -- are embroidered in a distinct spiral pattern, creating a realistic effect.

Finally the completed picture is framed in a silk brocade border similar to the borders in which painted thangkas are also framed.

Because all work is done by hand to precise standards, a single artist will require several months to complete one thangka. Often, a team of artist-tailors work together to produce a thangka, particularly when that thangka is large or especially detailed.

In general, appliqué thangkas are less detailed than their painted counterparts, especially when they are of similar size. Most appliqué thangkas portray a single deity, usually of the peaceful variety. This is due to the nature of the material and the technique. We see relatively few small appliqué thangkas of wrathful or elaborate tantric deities, because inherent characteristics of the fabrics make it extremely difficult to render small details accurately below a certain size.

Discrepancies in Descriptions of Technique

Eleanor Olson wrote in 1950, “In many of the hangings the pieces, after being joined, are outlined by a thin, delicate cord whipped over with colored silks used not only to define the pattern but to delineate as well certain details such as features and folds in the skin.” (emphasis mine). I would guess that her assumption that the cords were applied after pieces were joined was an error derived from seeing only finished pieces, rather than works in production. In my experience, the cords which define and delineate, are always applied before the pieces are joined.

Some descriptions indicate or imply that early fabric thangkas were constructed by placing pieces of brocade onto a cotton backing on which the image was drawn. And Diana Myers and Françoise Pommaret write of the appliqué thangkas in Bhutan, “Once the component sections are ready , they are stitched one by one to the background cloth until the thangka is complete.” (p. 155) If these descriptions are accurate, then there exists (or existed) a different technique than that used later in Tibet and currently by Tibetans in India and Nepal. I do not yet know whether these mentions of a background cloth stem from a misunderstanding or whether they point to the existence of a variation of Tibetan appliqué in which pieces are attached to a backing. It is also possible that such a background cloth, though not necessary in smaller thangkas, is (or was) used in giant thangkas in order to give stability to the large expanse of assembled pieces.

Another variation that certainly exists is that of paper-backed cut-and-glued appliqué. I don't know how far back this tradition dates, but it is probably of more recent origin than the stitched appliqué and seems to have originated in the eastern Tibetan region of Amdo. Today, it is carried on by Tibetans in and from the area of Regong Monastery and elsewhere by Leslie Nguyen Temple. Olson was aware of it in 1950, because she wrote, “In other instances each separate unit is made up of silk sewn over a paper foundation cut to the shape required and without any additional outline... Occasionally details are painted.” Though she indicates that the silk was stitched to the paper shapes, these days it is glued and the details are painted or drawn. I am not qualified to comment any further on the specifics of this technique.

Social Structures of Appliqué Thangka Making

In Mongolia the stitching of appliqué thangkas was largely performed by women, according to N. Tsultem and D. Sandagdorzh's introduction to the book Mongol Zurag. They write that the "pictures-appliques" in that country were "made by women under the guidance of famous artists ..." In Bhutan and Tibet, however, though cloth was woven by women, cutting and stitching for religious and government purposes was men's work. Stitching of appliqué thangkas, therefore, was done almost exclusively by men -- both monks and laymen.

Olson notes that "The craftsmen are usually laymen, although, as in the case of Tibetan paintings, the responsibility for the composition rests with lamas who may draw the outlines or sketch the general plan, always according to the prescriptions of liturgical treatises. When a banner is completed a lama intervenes again to consecrate it."

In Lhasa before 1950, there was a tailors' guild, as well as a painters' guild, and a guild of artisans such as carpenters, gold and silver smiths, etc. These guilds were established in the 17th century by the 5th Dalai Lama. In the early 20th century, there were 700 tailors in the guild, including an elite group of the 130 most highly skilled, who fulfilled the government's tailoring needs. Registration was compulsory, and undeclared tailors received corporal punishment from members of the guild who sought them out and identified them by the needles stuck in their lapels and threads sticking to their wool clothes. (Gyeten Namgyal, A Tailor's Tale, p.31)

Though expert tailors tended to specialize in particular products, they were generally proficient in all fields of tailoring: clothing, ritual costumes, applique thangkas, and brocade frames for painted thangkas. They were experts in the qualities and behaviors of the various fabrics they employed as well as in the most efficient use of these fabrics. With the most precious or antique brocades, special attention was given to achieving the best result with the least possible material.

We know that in the 15th century, appliqué thangkas were designed and their construction supervised by well known master thangka painters.

Also in early 20th century Lhasa, drawings were made by painters and then interpreted in stitched silk by teams of tailors. Gyeten Namgyal recounts the difficulty painters had in understanding the demands of a different medium. The drawings they made were often overly detailed for the fabric work. I experienced this myself the first time I asked a highly skilled thangka painter to create a drawing for an appliqué thangka.

Today in India and Nepal, tailoring and appliqué workshops headed by a master tailor are staffed by male and female apprentices. Most are young Tibetans, either born in exile or recently arrived from Tibet. The majority are young women. These workshops produce big (though not GIANT) appliqué thangkas on commission for monasteries and Buddhist centers and make the brocade frames for hundreds of painted thangkas belonging to institutions and individuals. They also make clothing for monks and create other ritual textile items. Drawings for appliqué thangkas are still commissioned from thangka painting masters.

In Lhasa today, there is at least one Tibetan festival tent factory making appliqué thangkas. In collaboration with Temple Art Studio, they are restoring the lost giant thangka heritage of Tsurphu Monastery.

Even today in Tibet, the giant thangkas serve a special purpose when they are brought out periodically for the "sunning of the Buddha." It is a great blessing to gaze on the giant image. Viewers, patrons, and makers alike gain great merit -- positive energy for spiritual growth -- from their participation.

Smaller appliqué thangkas serve the same function as their painted counterparts -- as focal points on personal and temple altars -- but, being so much rarer, they are still particularly precious.

Note

Note:

Though I've attempted to be as thorough and accurate as possible and to document the sources of my information (when it doesn't come from my own experience making thangkas and living around Tibetans for several years), this is not a polished scholarly article, and I'm sure it does not meet academic standards. (We are on Squidoo, after all!) I am responsible for any errors or omissions and am eager to correct them to the best of my ability over time. Please feel free to write me with suggestions or contributions. I hope my writing can increase awareness, understanding, and appreciation for the precious art of fabric thangka.

Bibliography

Fisher, Robert E., "Art from the Himalayas," Asian Art: Selections from the Norton Simon Museum, edited by Pratapaditya Pal, pp. 58-59

Henss, Michael. "The Woven Image: Tibeto-Chinese Textile Thangkas of the Yuan and Early Ming Dynasties," November 1997, Chinese and Central Asian Textiles: Selected articles from Orientations 1983-1997, pp. 206-219

Jackson, David and Janice. Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials, London, Serinda Publications, 1984

Jackson, David. A History of Tibetan Painting: The Great Tibetan Painters and Their Traditions, Verlag Der Osterreichischen Akademie Der Wiss, 1996

Landaw, Jonathan and Weber, Andy. Images of Enlightenment: Tibetan Art in Practice, Ithaca, Snow Lion Publications, 1993

Myers, Diane K. and Bean, Susan S. From the Land of the Thunder Dragon: Textile Arts of Bhutan, London, Serinda Publications and Salem, Peabody Essex Museum, 1994

Namgyal, Gyeten as told to Kim Yeshi, "A Tailor's Tale," Chö Yang: The Voice of Tibetan Religion & Culture, No. 6, 1994, pp. 28-63

Nguyen Temple, Leslie and Terris, website www.tibetcolor.com

Olson, Eleanor. "Tibetan Applique Work," Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club, Vol. 34, 1950

Reynolds, Valrae. "Fabric Images and Their Special Role in Tibet," MARG Vol XLVIII, Edited by Pratapaditya Pal, Mumbai, Marg Publications

Reynolds, Valrae. "A Sino-Mongolian-Tibetan Buddhist Appliqué in the Newark Museum," April 1990, Chinese and Central Asian Textiles: Selected articles from Orientations 1983-1997, pp. 81-87

Reynolds, Valrae. "The Silk Road: From China to Tibet - and Back," May 1995, Chinese and Central Asian Textiles: Selected articles from Orientations 1983-1997, pp. 146-153

Reynolds, Valrae. "Buddhist Silk Textiles: Evidence for Patronage and Ritual Practice in China and Tibet," April 1997, Chinese and Central Asian Textiles: Selected articles from Orientations 1983-1997, pp. 188-199

Reynolds, Valrae. "From a Lost World: Tibetan Costumes and Textiles," March 1981, Art of Tibet: Selected articles from Orientations 1981-1997, pp. 4-20

Tsultem, N. and Sandagdorzh, D. Mongol Zurag, Ulan-Bator, State Publishing House, 1986

Van der Wee, L.P. "Tibetan Applique Hangings in European Collections," The Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club, Vol. 58, 1975

Threads of Awakening: my artist website - Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo's website

Please visit the informational pages of my website to learn more about Tibetan textile art:

- The tradition of silk applique thangka

Brief intro to the history and tradition of fabric thangkas - Threads of Awakening home page

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo's online hub for her work in the sacred Tibetan tradition of sewing sacred beauty - Stitching Buddhas Virtual Apprentice Program - Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo's teaching programs

Virtual apprenticeships in the Tibetan art of sewing sacred beauty. Your spiritual path. Your creative practice. Connected through ancient tradition. And delivered through modern technology.

Online Articles related to Tibetan Applique Thangkas

- Tibetan Applique Work (pdf)

"Tibetan Applique Work," article by Eleanor Olson for the Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club, Vol. 34 (1950), 23 pages (from the Online Digital Archive of Documents on Weaving and Related Subjects) - Tibetan Applique Hangings in European Collections (pdf)

"Tibetan Applique Hangings in European Collections," article by L.P. Van der Wee, The Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club, Vol. 58 (1975), 16 pages (from the Online Digital Archive of Documents on Weaving and Related Subjects) - Conservation of a Pang Khebs

How a lama dance costume at the Victoria and Albert Museum was restored - The Great Applique Tangka of Drepung Monastery

Article by Nancy Jo Johnson, 1999 - The Giant Thangkas of Tsurphu Monastery

by Terris Temple and Leslie Nguyen - Threads of Awakening: Buddhism in Art

by Alicia Doyle in Your Health Connection, March 2013 - Meditation with Needle and Thread

by Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo in Spirituality & Health, Jan-Feb 2011 - Oxnard Artist Specializes in Tibetan Appliqué

by Alicia Doyle, Ventura County Star, July 2012 - Endangered Tibetan art form blossoms in Italy

by Barbara Cornell, Reuters, Dec 2008 - Intersections: the work of Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo

by Leanne Jewett in Fiber Art Now, Fall 2012 - Virtual Buddhist Art Apprenticeships: Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo's Online Ancient Tibetan Spiritual Art F

by Meher McArthur on KCET Artbound, Dec 2012

Some Examples of Tibetan Applique in Museum Collections

This is a very incomplete list. There are also fine examples of Tibetan applique in the Newark Museum collection, among others.

- Future Buddha Maitreya Flanked by the Eighth Dalai Lama and His Tutor, 1793-94, Norton Simon Museum

The Norton Simon Museum of Art holds one of the world's finest and most prestigious collections. Search its collection online, featuring detailed information and color images of nearly 1,000 works of European, American and South Asian art. - Mongolian "silk paintings"

Introduction to the Art of Mongolia by Terese Tse Bartholomew, September 7, 1995, on Asianart.com - Phagspa Lama

Phagspa Lama Uran Namsarai (d. 1913) Silk applique H: 61 3/8 (155.0) W: 44 3/8 (112.6) on asianart.com

Related YouTube videos

Books on Tibetan Art - Mostly painting and sculpture

There's been very little written to date on this unique Tibetan textile art, but books on Tibetan painting, sculpture, and iconography can put it in context.