- HubPages»

- Arts and Design»

- Crafts & Handiwork»

- Paper Creations

How Is Paper Made?

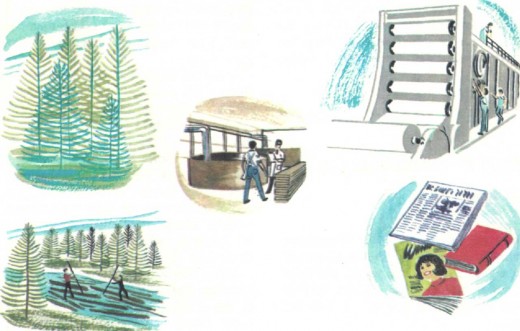

Paper is made of millions of tiny fibers. The fibers are cellulose, a substance from the cell walls of plants. The cellulose used in paper today comes mostly from trees.

When the bark of a tree log has been stripped off, the wood is ready to be turned into pulp. Pulping is done either by grinding up the wood or by cooking it with chemicals. Some pulping methods use both grinding and cooking.

The wood pulp is then screened and washed to clean out impurities and chemicals. It may then be bleached to make the paper whiter, so that printing or writing shows up better on it.

In the next step, the pulp is beaten in a large mixing machine and mixed with water. The beating frays the fibers, which helps them mat together. Starch, clay, or other materials may be added to improve the surface of the paper for printing and writing.

The pulp then goes into a machine called a Jordan refiner, where the fibers are trimmed evenly. At this stage the pulp consists of 99 per cent water and 1 per cent fiber. It is now ready to go into the paper-making machine.

In this machine, water drains out of the pulp through a screen, and suction pumps remove more water. The screen vibrates to make the fibers interlock and mat together. The wet mat then passes under a roller that presses it down into a smoother sheet.

The sheet goes through a series of pressing rolls, which squeeze out water and make the paper dense and smooth. Then it travels through a series of heated drums called driers. At this time a coating can be applied to make the paper smooth and shiny. Paper comes off the machines in large rolls. It is trimmed to take off the rough edges and cut to the desired width.

The History of Paper

Paper was invented by the Chinese, though our word (which is similar in other languages) derives from its predecessor, the papyrus of the ancient Mediterranean.

The Egyptians wrote on papyrus as far back as the third millennium B.C., and it was the main writing material of the Greco-Roman world for a thousand years. The tall sedge Cyperus papyri, from the stems of which it was made, grew in the marshes of Lower Egypt, and in less quantity in northern Palestine. Nowadays this plant grows chiefly in the Sudan and Abyssinia; and also in Sicily, near Syracuse, where it is still made into a special kind of paper.

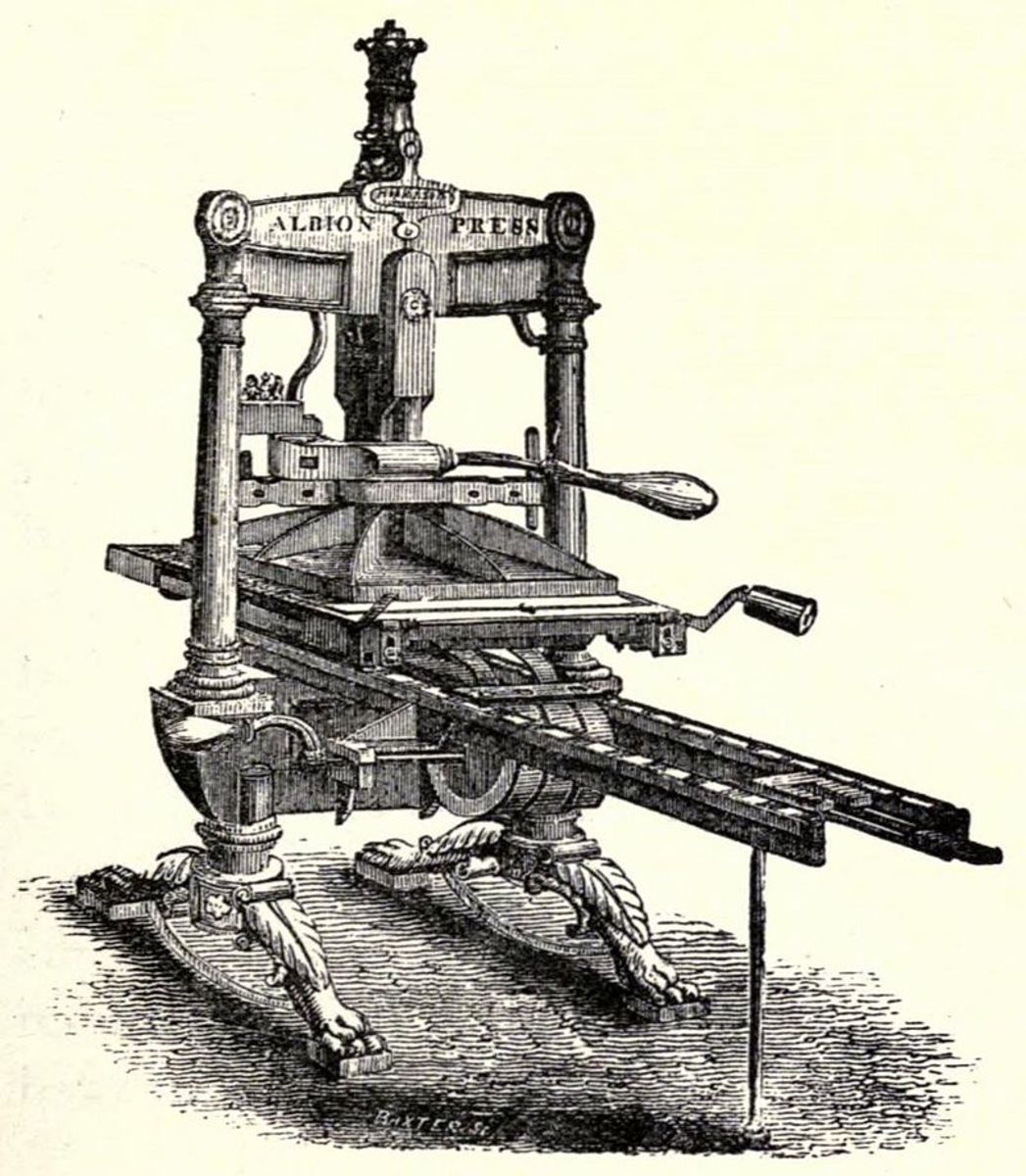

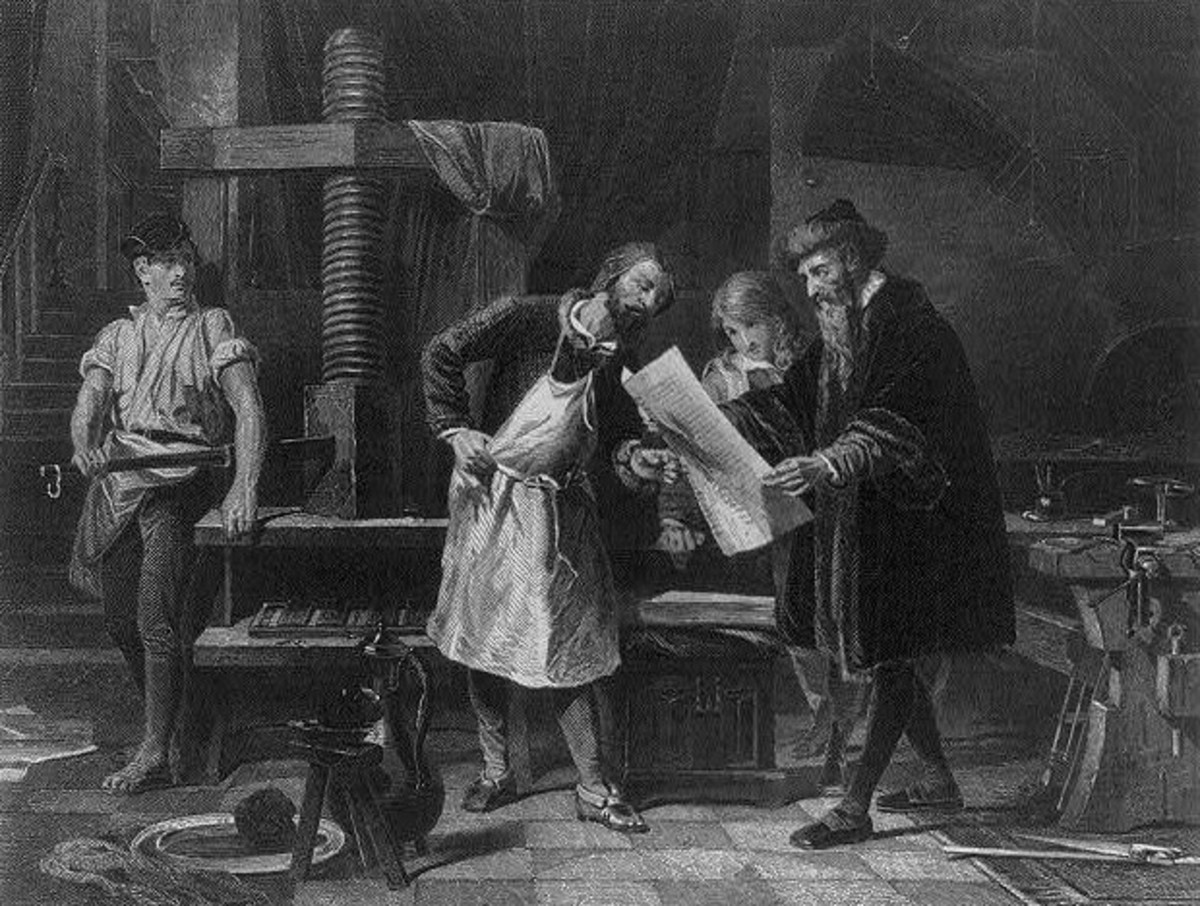

Though supremely important in ancient civilization and human history, papyrus had its drawbacks. Compacted in small sheets with the fibers criss-crossing at right angles, it was brittle; and the supply of the plant was limited geographically. Parchment or vellum, which became the literary writing material par excellence of the Middle Ages, also had its drawbacks and advantages. It was tougher and more durable than the fragile papyrus, the leaves could receive writing on both sides, and ink could easily be removed for corrections. There were not geographical limits to the supply of the raw skin from which parchment is prepared; but it was a costly material. Yet it served learning in the western world for well over eleven hundred years - from the time of the earliest vellum codices of the third or fourth century A.D. to the invention of the printing press in Europe about 1450, or rather to the spread of printing on paper in the second half of the fifteenth century.

Paper long preceded printing both in China and in Europe, and it would be fair enough to say, no paper, no printing and no printing press.

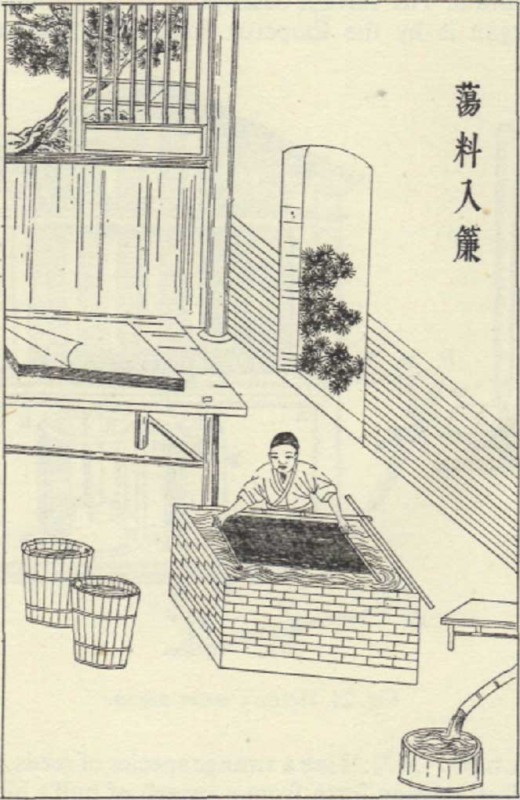

Traditionally, paper was invented by Ts'ai Lun, chief eunuch to the Emperor Ho Ti, in A.D. 105. Scraps of rag paper of about A.D. 150 were found in China by Sir Aurel Stein. The earliest extant documents on paper were discovered in 1899 in the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas near Tun Huang, in Kansu province. They are written in Sogdian, the language of a part of the ancient Persian empire. Until recently they were assigned to a period not later than the middle second century A.D., but it has been proved that they belong to A.D. 313 or 314. The good-quality paper of these documents is made entirely from rags of fabric woven of Chinese hemp (Bochineria nivea).

The Koreans and the Japanese learned paper-making from the Chinese in the seventh century; the Arabs in the eighth century learned the craft from Chinese prisoners, and Samarkand (now in Soviet Uzbekistan) was the first Muslim city where paper was produced. About A.D. 800 Baghdad and Damascus became important centers of paper manufacture. There are many Arabic paper manuscripts extant, belonging to the ninth century, and made of pure rag (from linen and flax). About 1100 paper was being made in Cairo, and soon after in Fez, in Morocco. At the same time, the Moslems introduced the craft into Spain, where paper-mills were soon working prosperously in Valencia, Toledo and Jativa: in the last-mentioned city a paper-mill is said to have existed in 1134.

The earliest known European document on paper is a deed of Countess Adelaide, wife of Roger I, the Norman conqueror of Sicily, dated 1102. It is written in Arabic and Greek, and preserved in the state archives at Palermo.

In Italy the earliest paper-mills were set up in the later twelfth century at Fabriano in the province of Ancona; where even now the mills are among the most important in the world. It is said that the craft was introduced into Fabriano by people returning from the Crusades. About 1200 Master Polese da Fabriano set up a mill in Bologna. In the early fourteenth century there were about forty mills at Fabriano; water-marking was first invented there. The craft soon spread to France (1248), Germany (early fourteenth century), Switzerland (1380), England (1450), the Netherlands (about the same time). In the fourteenth century paper became the main literary writing material in Europe, and in the course of the next century it gradually superseded parchment.

Paper was made by hand in separate sheets. In 1798 or 1799 a machine was devised by the Frenchman L.N.Robert for making it in a continuous web. In England the first machine for continuous paper-making in bulk was set up in Hertfordshire in 1803 by Henry Fourdrinier (1766-1854), aided by the notable engineer and inventor Bryan Donkin. The substance which the Imperial Eunuch had invented nearly seventeen hundred years before now proved itself more than ever one of the chief vectors of modern civilization, for good and all.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2009 Longtail