Methods of Mural Painting

Permanence and suitability to architectural surroundings are chief factors in the mural painter's choice of the medium to be used for a particular work. This choice will otherwise be dictated by the style of painting which the artist finds most adaptable to the expression of his idea. New media develop as the artists of a period find the established methods inadequate for their needs, and for this reason they are best studied in their historical contexts.

A widening knowledge of the history of art has brought about the appreciation of many little known styles and techniques of earlier times. Prehistoric man painted on the walls of caves in Altamira and the Dordogne. Of a much later time are the Buddhist paintings done on the walls of the cave temples of Ajanta in and prior to the 7th century A.D. In early Egypt and in Crete most murals were painted using flat color and linear silhouette, the earliest known being the famous Geese of Meidum belonging to the Egyptian Old Kingdom (2900-2750 B.C.). Of all the ancient works studied by painters of the modern era, probably those of the Egyptians, Greeks, and Pompeians have been most influential in forming Western mural styles.

Prehistoric cave painters made their drawings directly on the rough sandstone with natural earth pigments, much as pastel is used today: in most cases preservation is due to the accidental formation of a transparent film of limestone deposited by water seepage over their surfaces. Early painters mixed adhesive gum with their pigments, probably gum acacia or gum arable in the case of Egyptian mural works.

Cretan painting, such as that in the Palace of Knossos, around 1500 B.C., presents some of the earliest known examples of the use of fresco, which was to become one of the most important media employed in architectural decoration during many centuries. In this manner of painting the pigment is ground in water or lime water and applied to a surface of fine plaster before the plaster has become completely crystallized. The pigment is bound to the plaster surface through the interlocking of slowly forming crystals of lime carbonate, as the lime oxide returns to its original form upon exposure to the carbon dioxide of the air. An area of about a square yard is prepared and completed at a time, this being considered a day's work by the frescanti. Succeeding sections of plaster will show a fine indentation where they join; the indentations are planned to follow the edges of color planes in the design.

The traditional palette of the fresco painter is limited to the natural earth colors, such as yellow ochre and terra verte; the burnt earths, such as Venetian red; and a few other lime-fast colors, such as cobalt blue. Few organic dyes or synthetic colors are fast in the presence of lime. Pigments prepared by grinding potters' glazes or frit pigments found some use as early as Egyptian times. True fresco becomes more luminous with age, due to the increasing transparency of the plaster surface as the lime crystals become completely carbonated.

The process described above is that of true fresco, which requires that when a mistake has been made, the outer coat of that particular section of plaster must be removed and renewed. Retouching has sometimes been done with the use of fresco secco, or dry fresco, in which the binder is albumen or casein distemper; but it has seldom proved permanent. The Italians distinguish true fresco as "buon fresco."

True fresco and dry fresco both were practiced by the Greeks, Romans, and Pompeians, although the Roman artists preferred the harder materials of mosaic and stone inlay. True frescoes also appear in early Christian and Byzantine churches; but they rise to their greatest heights in works of the Italians of the Renaissance, beginning with the painter Cimabue. This fine fresco work followed a period in which mural painting had for a time been superseded as wall decoration by the mosaics of the Byzantines, as seen in Saint Sophia, at Ravenna, and at St. Mark's in Venice; and by the stained glass of the Gothic north.

Two great schools of art developed at this time in northern Italy, producing murals done in both fresco and tempera. These were of the school of Giotto and his followers, whose works may be seen in the lower church of St. Francis at Assisi, in the churches of Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella at Florence, and in the Arena Chapel at Padua; and the school of Siena. Artists of both schools traveled widely and influenced art in other regions. The work of the Sienese remained essentially medieval in character, while the art of the Florentines, followers of Giotto, changed to meet the needs of the new and spreading doctrine of humanism. Masaccio's mural painting, The Tribute Money in the Bran-cacci chapel of the church of Santa Maria della Carmine at Florence, signaled a further development in style from Giottesque painting; and during the 15th century other distinctive styles developed in Umbria, Rome, and northern Italy.

As men's attention became diverted from the medieval preoccupation with extra-worldly matters to an examination of the world around them, painting kept pace with scientific observation. Artists, reimbued with the Greek ideal of man as the center of all things, painted and anatomized the human figure, developed theories of vision which became laws of light and shade and mathematical perspective. Piero della Francesca of Umbria, in his magnificent frescoes at Arezzo depicting the Visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon, demonstrated his scientific knowledge of architectural geometry and anatomy in common with Greek idealization of the human figure, which had become the Florentine goal in painting. Luca Signorelli, in his murals of the Last Judgment in the Cathedral at Orvieto, exhibits knowledge of the anatomy and movement of the human figure rather than concern with religious symbolization.

Two fresco painters who emerged from the Florentine group executed works in Rome in the first half of the 16th century which may be said to have exerted more influence upon the art of the Western World than any other paintings until comparatively recent times. One of these was Raphael Sanzio, whose Umbrian studies under Perugino are thought to account for his rich use of color. Raphael's Vatican frescoes known as the Stanse have long been models for students of classic work. Michelangelo Buonarroti, who considered himself primarily a sculptor, became a prisoner of war in the attack of Pope Julian's forces upon the Florentine Republic and was ordered, in spite of his protest, to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in fresco. As an architect, engineer, and sculptor, Michelangelo was in disagreement with the round-vaulted ceiling. He used his Florentine knowledge of space drawing to destroy its architectural effect. Instead we see a series of flat, bas-relief sculptural panels symbolizing the Creation, divided by painted beams, supported in turn by painted pilasters. The power and magnificence of the work is unquestioned. It remains a tour de force of the art of fresco, but it is also a great monument to a rebellious spirit, by which the mural painter demonstrated his refusal to approve the architecture of which his work was a part.

The style of Florentine painting was developed in terms of the use of fresco and tempera; both media encourage careful, planned work with reliance upon clearly drawn outlines, in a color range somewhat more limited than that of oil paint. The tempera medium was much used for smaller works of both Sienese and Florentine schools, executed upon wood panels first coated with gesso, a preparation of plaster and glue, employing egg yolk as a binder.

Early Flemish painters of northern Europe adopted as binding media linseed oil (oil of flax-seed) and varnishes prepared from pine pitch, in creating miniatures and small paintings to harmonize with the rich wood-paneled interiors of their region. Wall spaces which in the southern countries would call for large mural decorations here were needed for light-giving stained glass. The deep, enamel-like brilliance of underpainting and overglazing was well suited to their purposes.

It is believed that Domenico Veneziano, a Florentine traveler, introduced the northern craft of oil painting to the Florentines; but not until the sensuous Venetians rebelled against Florence's intellectual abstraction did the rich effects of oil painting become exploited in the mural decorations of Italy. Titian, a successful fresco painter early in his career in the Scuola del Santo at Padua, later became a virtuoso in the oil paint medium. His Assumption for the church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice, is the first oil painting to contain human figures as large as those in the biggest frescoes. Unfortunately Titian's murals for the Palace of the Doges were destroyed by fire; they were considered by contemporaries to be his greatest.

Titian's vigorous and glowing work was carried forward by Jacopo Robusti, known as Tintoretto. The careful, craftsmanlike processes which characterized the methods of the Florentines could not compete with the free, direct painting and the ease of correction of errors offered by the oil method.

Many baroque palaces of the time were richly decorated after the Venetian manner. Paolo Cagliari, known as Veronese, excelled in creating scenes of pompous splendor; his ceiling for the Doges' Palace, and various paintings for the church of San Sebastiano were typical examples of the mural work then most acceptable. Peter Paul Rubens, basing his style upon the works of Veronese, Michelangelo, and Raphael, carried the international baroque manner through all of Europe's capitals. Among his mural commissions were the decorations for the Luxembourg Palace for Marie de' Medici and the ceiling of Whitehall in England. In Spain, Domenikos Theotokopoulos, called El Greco, executed somber, emotionally intense decorations which combined Byzantine abstraction with Venetian breadth. His Burial of the Count of Orgaz in the Church of Santo Tome at Toledo, is one of his best known works.

The French baroque style may be represented by the frescoes done in the Church of Val de Grace by Pierre Mignard, who headed the official French Academy under Louis XIV.

Mural painting enters a lighter phase in the rococo period which followed. Representative of his times as a mural decorator was Francois Boucher, whose work appears in yersailles, in the Bibliotheque Nationale at Fontainebleau and in the chateau of Madame de Pompadour at Bellevue.

Neither the neoclassic period nor the era of romanticism which followed were good ones for mural work; but Jacques-Louis David among neoclassicists and the romantic Theodore Chas-seriau, who influenced Puvis de Chavannes, left enough impression upon later muralists to deserve mention.

Mural painting in England and Germany paralleled French work to some extent and included experimentation with fresco, oil, and tempera media and also spirit-fresco, a kind of wax painting, and water-glass. In Germany the names of Peter von Cornelius, Peter yon Hess, Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and Wilhem von Kaul-bach come to the fore. In Engand a revival of mural decoration was carried forward in Victorian times by Thomas Gambier Parry, Charles West Cope, Sir Edward Poynter, and Frank Brangwyn, whose murals, executed for the San Francisco Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915, are now set into the walls of the Veterans' Memorial Theater in San Francisco. These last are excellent examples of the influence of Impressionist light painting upon the art of the mural.

Most innovations have represented attempts to reproduce the quality of classic fresco without bowing to its limitations. Since the end of the Renaissance period, with the increasing separation in interests of painter and architect, a great majority of mural decorations have been executed for buildings already in use, making fresco inconvenient. In addition, reinforced concrete construction is chemically inimical to fresco unless elaborate precautions are taken to insulate the fresco plaster from metal or concrete. Oil paint as a medium is sensitive not only to free alkali from plaster, but also to moisture; careful priming is necessary. Also to be considered is the fact that many modern buildings are relatively impermanent ; a work of art which is an integral part of the structure is difficult to save when it is torn down. It is little wonder that the French method of marouflage has been used by modern muralists for many years: affixing to a wall a canvas previously painted in the studio. This practice has indeed often obscured the difference between easel and mural painting; many a mural has been executed by an artist who may never have seen the building in which it would go, and who might be only vaguely aware of the color and scale of the rooms or walls involved. This is said to be true of the murals done by Puvis de Chavannes for the Boston Public Library, and of the abstractions more recently contributed by Fernand Leger to the auditorium of the United Nations building in New York City.

The first true mural paintings executed in the United States were those done by John La Farge for the Trinity Church in Boston in 1876. With the work of this painter and his group began the development of American mural painting as a consciously distinct art. Associated with La Farge in this enterprise and others were William Morris Hunt, Edwin Austin Abbey, Henry O. Walker, Kenyon Cox, John Singer Sargent, and Edwin Blashfield. In his book, Mural Painting in America (1913), Blashfield stresses the debt of American mural painters to the training of Paris and the continued study of Renaissance masters, as well as modern influences like their favorite, de Chavannes.

These painters borrowed not only the style, but also the systems of symbols used by classic and European muralists. Greek and Roman deities or Biblical personages sometimes appear incongruous as symbols for forces of the modern world. Figures from American history in classic garb or in classic nudity appear in many mural paintings of the time. Only in later years did costumes of the period become acceptable in monumental works.

After admitting the neoclassic and eclectic nature of this first American school of mural painting, Blashfield goes on to say: "The style of Perugino and Pinturricchio is very beautiful, and may be used to great advantage in America, but it is not final; no style is." With public approval of the work of this group, which appeared in the 1891-1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, their style became established in spite of Blashfield's wise prediction. So long as America's leading architectural firms were dominated by the official style of the French Beaux-Arts Academy, mural painting in large public buildings conformed to the classic-baroque tradition, even after most easel painters had long since discarded it.

As European styles of painting changed, so did those of America, and American mural painting responded, although slowly. Romanticism, with emphasis on emotion, is reflected in the works of John Singer Sargent. Impressionism, characterized by concern for atmosphere and light, is well represented in American mural painting by the works of the followers of the Englishman, Frank Brangwyn. But Cubism and Expressionism often involving obscure personal symbolism and formal ideas not yet understood by the public were for some time confined to the field of easel painting.

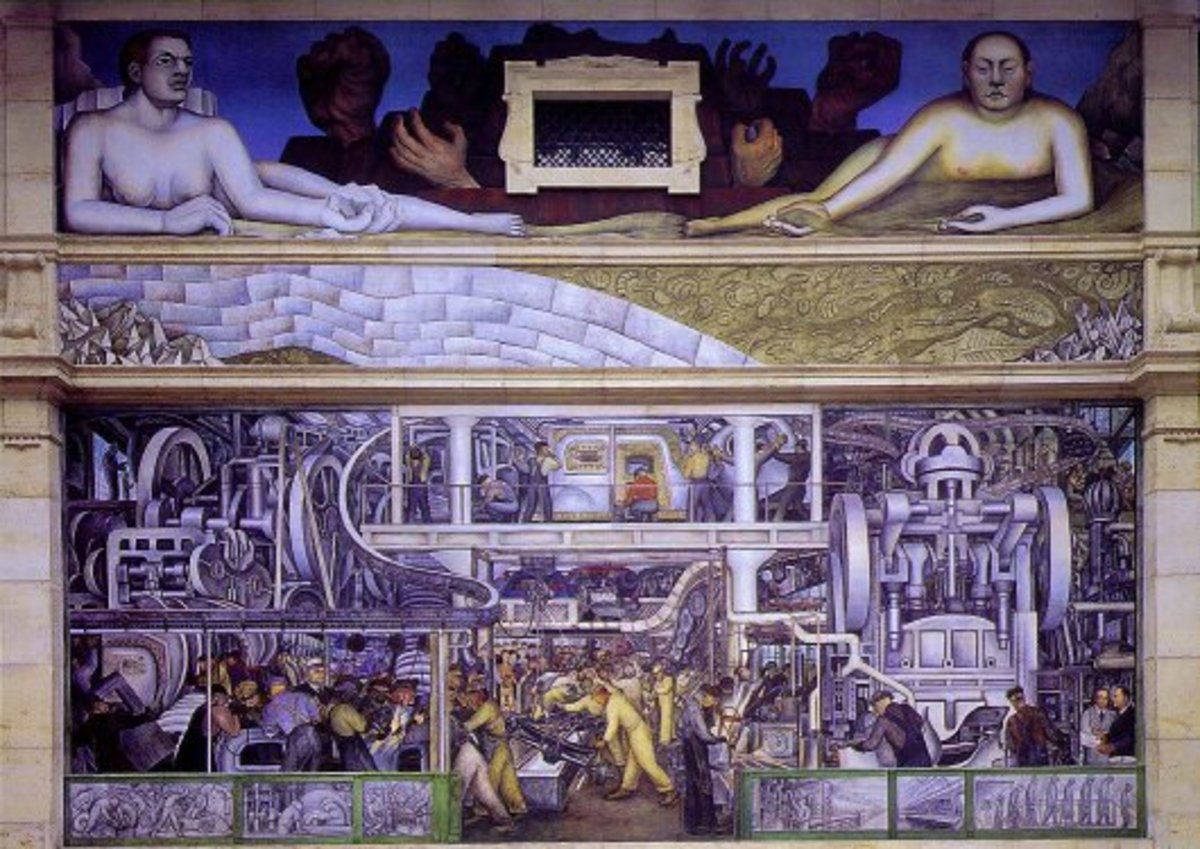

In the 1920's, attention was once more focused upon monumental mural painting by a group of artists for whom the Mexican revolution provided both theme and opportunity. The first important murals done by Diego Rivera appeared in the Mexican National Preparatory School, executed in encaustic. Here also Jose Clemente Orozco painted his first great frescoes. Work by David Alfaro Siqueiros, also done at this time, represented a successful attempt to combine fresco with encaustic. In spite of his unquestioned powers, Siqueiros' work displays a revolutionary violence and indifference to the accepted limitations of true mural work as to technique, form, and content.

These ambitious works ware only the first of a tremendous series of monumental decorations by Mexican painters. Rivera and Orozco also executed commissions in the United States, among which are those by Orozco at Detroit and at Pomona College in California, and by Rivera in the Stock Exchange of San Francisco. Rivera's projected frescoes for Rockefeller Center in New York City were never completed because of a disagreement with his sponsors regarding a representation of Lenin in the design.

This fresh impetus given to mural painting by the work of the Mexican painters strongly influenced many artists of the United States for the duration of the government art projects set up in the 1930's under the Roosevelt administration. An unexampled flow of many kinds of art work was produced, much of which took permanent form as mural decoration in public buildings throughout the country. On the Pacific slope, notably, muralists made use of rediscovered antique methods of architectural decoration, such as mosaic in its many forms, and the unique cut stone work, or opus sectile, to be seen in the Alameda County Court House, Oakland, California. .

The Public Works of Art Project of the Treasury awarded commissions through competitions in which a large number of competent artists participated. Among the works thus produced are the murals by Anton Refregier for the Rincon Branch of the Post Office at San Francisco. These consist of a series of casein paintings which may well be accepted as a norm of modern mural style. They present various symbols of the social progress of the State of California in a manner which is both contemporary and eclectic in the best sense.

Under the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration appeared many other works, such as the highly praised murals by Philip Guston, Maintaining America's Skills, for the New York World's Fair.

Although government art sponsorship lasted for only eight years, by this encouragement so many artists received training in mural painting, and understanding and public demand were so increased, that opportunity for the contemporary muralist in the United States has been greatly expanded. Almost no public building of any pretensions is now planned without considering the desirability of integrated architectural decoration, whether sculpture, mosaic, inlaid stone or true mural painting.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2010 Longtail