Howmet TX Gas Turbine Race Car

The World's Most Successful Gas Turbine Race Car

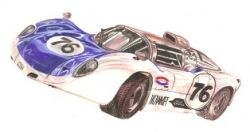

The Howmet TX was one of the world's first and most successful turbine race cars. It was - and after more than 40 years still is - years ahead of its time in beauty, engineering and audacity.

During 1968, two Howmet TX cars ran in 15 races, with a total of four wins. In addition, it placed second or third in three other races. The Howmet ended the season at the prestigious Le Mans 24-hour race, although both vehicles failed to finish. While it never raced again, it set six speed records for turbine cars in 1970 before its retirement.

Virtues and Vices Give Birth to a Race Car

Driver Ray Heppenstall teams up with the Howmet Company

It was a mixture of human virtues and vices that coalesced to give birth to one of the most amazing, albeit short-lived race cars of history.

While America was building a vehicle that would carry man to the moon in the late 1960s, the racing industry was applying innovation and competitiveness to the sport in a way never previously experienced. The audacious spirit of the engineers reaching to the moon was no greater than that of entrepreneur-turned-race-car-driver Ray Heppenstall.

It was in 1963 that race car driver Ray Heppenstall first talked to Howmet about building a turbine race car. In the previous decade Howmet had transformed itself from a mining company to a manufacturer of specialty metals and alloys. One division focused on aluminum and another on surgical implants. Both would eventually play a role in the later development of the race car, but the implant side of the business was the first connection. Because of their expertise in working with alloys needed for surgical implants, Howmet had branched into the field of high-temperature, precision blades needed for turbine engines. Such super-powered engines were found in jet planes, helicopters and even electric generators - but certainly not cars. The car's name would reflect this audacity - the Howmet TX - for Turbine Experimental.

Understanding the Gas Turbine Engine

They're more at home in aircraft or tuna boats.

A turbine is the name for a set of blades mounted on a wheel, which is turned by the pressure of air, steam, water, or hot gasses. Turbine engines are fundamentally different than internal combustion engines. Overall, they are simpler in design and can contain up to 80 percent fewer parts. This means they can weigh less, have fewer moving parts and require less maintenance than a piston engine.

A gas turbine engine has three components. At the front, or intake of the engine, a set of blades called a compressor forces air into an ignition chamber. There, fuel is introduced and the resulting explosion creates rapidly expanding gases, which turn a set of turbine blades at the rear of the engine. The result is rotary energy from the turbine shaft, as well as thrust from the exhaust gases and excess heat. A portion of energy created by the rotating turbine shaft is used to turn the upstream compressor blades.

Race Car Resources on Amazon

Check out these items that touch on the Howmett TX and other classic race cars of this era.

TX Development Part of Howmet's Public Relations Efforts

Car was part of efforts to impress investors.

Howmet's transformation from mining company to specialty metal manufactuer did not produce positive results in the same manner as a turbine engine produces energy. Instead the changes had lead to reduced profits and a dramatic drop in stock price - from $29 to $15 per share. The company had potential, but was undervalued, which attracted the attention of Pechiney, a French aluminum company. Pechiney began buying shares and eventually soon acquired 46 percent of the company. By 1965, 42-year-od John J. Burke, an aerospace executive, became president of the company. Heppenstall recalls that Burke "saw the handwriting on the wall" and undertook a two-fold campaign to revive the company's fortunes and enhance the corporate image.

Burke sold off unpromising parts of the company and avoided any new acquisitions in order to bolster the stock price, but his public relation efforts were equally significant. He shortened the company name to Howmet from Howe Sound, a name related to an inlet along the Pacific coast of British Columbia where the company had originally had copper mining interests in 1906. "We all got completely fed up with explaining to people that we didn't make stereo sets, tape recorders, or any sort of hearing aid," Burke said.

The Howmet TX race car was another part of the plan to impress investors. During its five-month career, the race car was featured on network television 21 times, including twice on NBC's Huntley Brinkley Report. The company's investment in the Howmet TX project was a modest $160,000, but in the end, the two-part plan worked. Howmet's stock price soared, reaching nearly $100 per share in 1968 before a stock split. Burke conveniently moved up to chairman of the board as a Pechiney executive became president, exercised his stock options reported to be worth $10 million, and retired. Whether seen as virtue or vice, the pursuit of profit at Howmet made executives like Burke rich, rewarded stockholders, and also created an auto racing legend.

Moving Beyond Planes, Continental Aviation Helps Build a Turbine Car

TX's turbine originally designed for military helicopter

it was engineering virtue that drove the involvement of Continental Aviation and Engineering (now Teledyne Continental). The company was identified as the ideal supplier for a turbine engine. They had recently lost a bid with U.S. government to develop a turbine engine for a light observation helicopter. As a result, they had 10 leftover engines. Howmet took two of the engines, one for each of two matching cars to be built. As a military engine, the blueprints were actually classified, and eventually after the car finished its racing career, the engines were returned to Continental. The engine was "a neat little package," according to Heppenstall. It weighed 170 lbs and developed 330 HP. The FIA, the international governing body for racing, had developed a formula for measuring equivalency compared to traditional combustion engines. Using mathematical calculations rather than measurements, the FIA rated the engine at 2960cc, thus identifying the engine's size just under three liters.

The Continental engines were installed into a conventional tubular space-frame chassis built by Bob McKee, a well-known sports car constructor. In order to harness the turbine's power, a special design was required to transfer power to the wheels. To achieve this, the free turbine design was implemented. The result functioned something like an automatic transmission. Exhaust gases were routed to a second turbine where the output shaft could spin at a variable speed depending on quantity of exhaust flowing into it. McKee built a transaxle that geared down the resulting energy and connected directly to the rear wheels, without a clutch. Reverse gear was provided separately by an electric starter motor. In the end, the gas turbine produced 57,000 RPM which was reduced to 6,700 at the driveshaft. It ran on JP-5 jet fuel from a 32-gallon tank between the driver's compartment and the engine.

The 'Wastegate' Solves a Key Turbine Problem

Spilling energy with a butterfly solves problem with accelerator lag time.

One of the key challenges of adapting turbine power to a race car is time lag between a change in the throttle and the resulting change in the engine’s power output. Continental engineers explained to Heppenstall that from the time you put your foot on the accelerator until the time you began to accelerate there would be a three-second turbine lag. “As a driver, I shuddered at the thought of this,” Heppenstall said, “Then they explained to me that there's a similar three-second delay on deceleration. I said ‘No. No. No.’”

Fortunately, there was an engineering solution, and one that Heppenstall had previously seen while glancing at report of turbine installed in a Pontiac Chieftain by Allison, another manufacturer of turbine engines. It involved installing a wastegate manifold. This was essentially a butterfly valve that opened to dump excess gases, or closed to increase power. This allowed the turbine to run at a constant speed for efficiency, although – as typical for turbine engines – fuel mileage was poor.

Using the wastegate approach, the first third of the throttle pedal’s movement was designed to control the fuel to the turbine, while the final two thirds of the pedal opened or closed the wastegate.

Testing the Howmet TX on the Streets of Detroit, Michigan

The police officer who tried to pull Heppenstall over clocked it at 105 MPH.

The engine was mated to the chassis at a Continental in Detroit, there but a test track was not readily available. Instead, on a Saturday morning, with a dealer plate hung on the back of the car and a chase car behind him, Heppenstall took a test drive around the plant on the city streets. The chase car was quickly lost in traffic, but was replaced by a police car. Heppenstall turned off onto a residential street and accelerated smoothly for a city block with no sensation of speed. Due to the noise of the turbine engine, the lack of visibility through the back window due to heat deflection, and without any mirrors, Heppenstall was unaware the police car was chasing him with its siren wailing. "The cop pulled up alongside me and wanted me to stop," Heppenstall said. "I refused, signaling him to follow me back to the Continental plant, where I stopped and awaited his consternation."

The officer "wanted to know what I thought I was doing," Heppenstall said. "I said I just finished the car and had no test track to go to, but wanted to see if it worked. He said, 'Fine, but if you want to go out on the road again, give us a call and we'll give you an escort.'" The Howmet was equipped with a tachometer, but not yet a speedometer; however, the officer was able to tell him that he clocked 105 MPH.

The Car that Doesn't Understand Running Slow

TX's virtue turns to vice as car crashes when wastegate fails.

“The real problem is the car doesn't understand running slow,” Heppenstall said of the Howmet TX at its premier in Daytona. Unfortunately, this was truly the car’s vice. In fact, problems with the wastegate providing too much power were the cause of several crashes. The wastegate needed to open and close dependably in red hot conditions, but on lap 34 at the 24 Hours of Daytona race in February 1968, the wastegate failed to open as driver Ed Lowther entered a corner. The Howmet hit a retaining wall and had to retire. The wastegate trouble reoccurred at the BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch in April. On lap seven the wastegate stuck and driver Dick Thompson went off the road hitting a bank.

Turbine Power Packaged in Beauty

Aluminum and Curves Make a Sexy Car

Surprisingly, the Howmet TX's raw power came packaged with the virtue of beauty. The skin of the car was crafted primarily from aluminum at a time when fiberglass was beginning to gain in popularity. he choice of metal was essential to emphasize Howmet's strengths in the aluminum industry. The curved windshield with its single wiper blade had been pulled by Heppenstall from a Porche 906. It featured gull-wing doors, wing mirrors, and was fitted with Halibrand cast-alloy wheels. The result was a sleek automobile standing only 37 inches tall with curves that look perpetually modern.

Where is the Howmet TX Today?

Several originals remain in the hands of collectors, but the dream lives on for all.

Today, the original two cars, designated chassis #1 and chassis #2, are owned by collectors, as is a replica built by McKee from the spare, never-raced chassis #3. Self-made engineer and driver Ray Heppenstall died in 2004.

Yet although the summer of 1968 is long past, the virtues and vices that created the Howmet TX are still alive. While those forces and human nature endure, race fans can look forward to the day that another car will capture their imagination to the extent that the Howmet did in 1968. Until then, we remember the Howmet TX, the world’s most successful turbine race car.