Defence Procurements, Policy, Procedure, Process and Practice: An Industry Perspective

An invaluable article that provides in-depth research and insights into the defence Procurement Process, Procedures and Practice and provides an industry perspective. The writer contends that the way forward is to promote the Buy and Make Indian procedure to be the default procedure. Buy Global acquisitions should be the last resort as the MoD and the Indian regulatory framework leak like a sieve in the monitoring of offset contracts and no real capacity is being built through this process.

On the other hand in Buy and Make Indian categorisations, foreign OEMs will have no choice but to engage with Indian industry, both DPSUs and Private, to win projects in India. Since these are competitive no Indian Prime will ever accept loading the commercials with ToT costs as that would be lose-lose for both foreign OEM and Indian Prime. Therefore, the Non-recurring Expenditure burden would have to be mostly borne by the foreign OEM and hence the induction of technology would be cheaper and faster. Forming JVs with Indian partners will build Indian capacity and open the route for India to become part of the global supply chain for the aerospace and defence industry. This would also promote Indian industry to innovate, something it cannot do as a mere offset partner.

This is a project of strategic importance for the aerospace sector of our country. This project can lay the foundations for a flourishing and genuine indigenous aerospace industry in India of the future. This one project would determine if India is to remain a screwdriver technology nation under the licensed production route or build genuine capability through Joint Ventures / Consortia under the Buy and Make Indian Route with 50 per cent indigenous content and only 10 per cent proprietary technology with OEM. So far the lead players, apart from TATA Group, would be Mahindra & Mahindra and L&T. There are a large number of other players such as GMR, Punj Lloyd, Axis, TAAL etc. who have specific strengths and would partner with the Prime Contractor in some way or the other. In addition, many vendors in the SME segment are already supplying world class products to HAL. Of course, engines would have to be imported but given the numbers creating a final assembly and engine test bed in India, purely as a business proposition is also attractive

In 1801, the East India Company set up a Gun and Shell Factory at Cossipore. Thus were sown the seeds of the Indian defence industry. From these very humble beginnings today, India has 39+1 Ordnance Factories and eight DPSUs which have been the primary source of indigenous procurement for the Indian Armed Forces. Despite substantial investments in capacity building, partnering and license production agreements with foreign OEMs, defence procurements continue to hover around the 70 per cent (imported) and 30 per cent (indigenous) ratio. Matters are further compounded by the large order book position of the OFBs and the DPSUs resulting in very large waiting period for the induction of scarce and highly important acquisition assets. Consequently, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) has initiated various processes to involve the Indian private sector as well as global players into the acquisition process. This article presents an overview of the defence procurement, procedure, process and practice.

Licensing Industrial licenses are granted under Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951 (65 of 1951) (IDR Act). The Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 divided industry into three parts:

Schedule 1: Basic industries which are the preserve of the state, including defence and heavy engineering.

Schedule 2: Industries in which private industry was allowed to operate.

Schedule 3: All other industries

.

Defence production has been kept under licensing regime to regulate the operation of defence industries including export of defence equipment. Until 1991, defence production was the exclusive preserve of the state and vide Gazette Notification (Part II) No. 412 dated 25.07.1991, the government initiated the liberalisation process and made fundamental changes in the IDR Act. Thus, defence and aerospace industries were kept, both in Schedule 1 (Industries reserved for public sector) and Schedule 2 (Industries requiring compulsory licensing). When the defence industry was opened for private sector participation through Press Note 4 of 2001 and Press Note 2 of 2002, the defence and aerospace industries were removed from Schedule 1 through notification No. S.O. 11(E) dated 03.01.2002. Subsequently, in 2004 the government of India set up a committee under Mr Vijay Kelkar to recommend measures to bring about improvements in defence acquisitions and production. Some of these recommendations were approved and the defence and aerospace industry remained no more the monopoly of public sector but still needing industrial license.

Licenses are granted on the basis of the classification of the product. However, as per the existing practice there is inadequate common understanding of what is a defence product that falls under the ambit of licenses. Presently, defence products classification codes are drawn from the following sources:

ITC (HS) code

Applications for industrial license require a clear definition of the defence items to be manufactured, assembled or integrated. The basis for items requiring industrial license is the Indian Trade Classification (Homogeneous Series) (ITC (HS) of DGCIS, Ministry of Commerce. Accordingly, following defence items are included under compulsory licensing regime:

Code: Item Description

87.10 : Tanks and other armoured fighting vehicles

8801 to 8805 : Defence aircraft, spacecraft and parts thereof

890601 : Warships of all kinds

9301 to 9307 : Arms and ammunitions; parts and accessories thereof

The ITC (HS) classification does not include many defence items.

NIC codes

The National Industrial Classification (NIC) is an essential Statistical Standard for developing and maintaining comparable database according to economic activities. Economic units engaged in the same or similar kind of economic activity are classified in the same category of the NIC. Industrial licenses require applicants to furnish the NIC Codes in their applications. Unlike the other sectors where product classification is fairly elaborate the defence industry classification codes are at best vague. It is quite difficult for an applicant to determine the precise code that would best reflect the activity that the applicant wishes to engage in the defence and aerospace sector. The following classification illustrates the vagueness of the definition:

• 301: Building of ships and boats

• 30112: Building of warships and scientific investigation ships etc.

• 303: Manufacture of air and spacecraft and related machinery

• 3030: Manufacture of air and spacecraft and related machinery

• 30301: Manufacture of airplanes

• 30302: Manufacture of helicopters

• 30303: Manufacture of gliders, hang-gliders, dirigibles and hot air balloons and other non-powered aircraft

• 30304: Manufacture of spacecraft and launch vehicles, satellites, planetary probes, orbital stations, shuttles, intercontinental ballistic (ICBM) and similar missiles

• 30305: Manufacture of parts and accessories of the aircraft and spacecraft of this class (major assemblies such as fuselages, wings, doors, control surfaces, landing gear, fuel tanks, nacelles, airscrews, helicopter rotors and propelled rotor blades, motors and engines of a kind typically found on aircraft, parts of turbojets and turbo propellers for aircraft, aircraft seats etc. and other specialised

parts of spacecraft)

It is evident that definition of defence items requiring industrial license is nebulous and open for interpretation.

Industrial Licenses for defence products are granted by Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP). So far about 178 licenses have been accorded by DIPP but it is well known that there are many more suppliers of “defence products”. There is also the issue of making a distinction between prototypes and development projects and serial production. The first apparently does not require a license but serial production does.

Domestic sale of defence equipment

The sale of defence equipment, which itself is a very subjective definition as has been seen above, either by NIC Codes or following ITC (HS) Codes, is governed by Para 15 of DIPP Press Note 2 of 2002. For domestic sales it has been said that the customer can only be the MoD and only after approval of the MoD can sell to even other ministries and entities be made.

In Buy and Make Indian categorisations, foreign OEMs will have no choice but to engage with Indian industry, both DPSU and Private, to win projects in India. Since these are competitive no Indian Prime will ever accept loading the commercials with ToT costs as that would be lose-lose for both foreign OEM and Indian Prime. Therefore, the Non-recurring Expenditure burden would have to be mostly borne by the foreign OEM and hence the induction of technology would be cheaper and faster. Forming JVs with Indian partners will build Indian capacity and open the route for India to become part of the global supply chain for the aerospace and defence industry. This would also promote Indian industry to innovate, something it cannot do as a mere offset partner

Exports of defence products

The base document governing exports is the Foreign Trade Policy. Export of dual-use items and technologies is either prohibited or is only permitted under a license. In Foreign Trade Policy, dual-use items have been given the nomenclature of Special Chemicals, Organisms, Materials, Equipment and Technologies (SCOMET). Export Policy relating to SCOMET items is given in Appendix 3 of Schedule 2 of ITC (HS) Classification and Paragraph 2.49 of Handbook of Procedures Vol-I, 2009-14. Appendix 3 of Schedule 2 of ITC (HS) Classification contains a list of all dual-use items and technologies export of which is regulated. Category 5 and Category 7 of the SCOMET List refers to the defence electronics and the aerospace sector. It is relevant to note that Export licenses are controlled by DGFT.

Partnerships and collaborations

Norms for JVs are issued by DIPP vide Circular 01/2012. The cap on equity participation in the defence sector is 26 per cent and the issue is under debate. Only permission for about 26 JVs (up to March 2012) have been accorded so far with leading industrial houses denied JVs on grounds best known to the government but clearly the public perception is that this denial is to protect the DPSUs from professional competition. That FDI in the defence sector has not succeeded despite the potential of over US$ 100 billion over the next two plan periods indicates something for the wise. As per DIPPs FDI statistics, issued in April 2012, the defence sector has received only US$ 3.8 million since the FDI norms were announced and ranks amongst the bottom three of sectoral FDI.

Procedures

Background and context

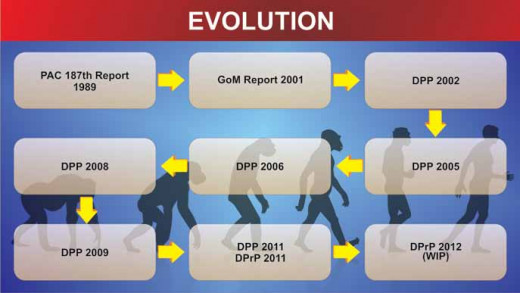

The Public Accounts Committee, Lok Sabha, in their 187th Report (1989) recommended that government should draw up comprehensive guidelines with regard

to negotiations and implementation of defence contracts. Based on the above recommendation of PAC, (and Expert Committee Report of 1986), the Ministry of Defence issued guidelines for all procurement cases involving an outlay of Rs 10.0 crore or more on 28 February 1992. It is commonly referred to as Defence Procurement Procedure 1992 (DPP-1992). This section traces the evolution of the defence procurement procedures.

DPP-1992

DPP-1992 laid down the steps to be followed for defence procurements. Though DPP-1992 was a creditable effort as it covered all activities pertaining to procurement, it suffered from several inadequacies which became apparent in its implementation over the years.

The MoD has also taken some brave baby steps in opening up complex projects under the Make category to the private sector. Of particular note are the Tactical Communications System (TCS) and the Future Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) projects. For the TCS project two contenders, a consortium of Larsen & Toubro, Tata Power SED and HCL Infosystems Ltd and Bharat Electronics Limited, are in contention for the Indian Army's Tactical Communications Systems (TCS) Project. The project is worth Rs 10,000 crore. This is the first project under the 'Buy Indian, Make Indian' clause introduced in the Defence Procurement Policy (DPP) 2011, The FICV is by far India’s biggest-ever land systems contract for production of 2,600 FICVs to replace ageing BMP-2 vehicles.

DPP-2002

Defence Procurement Procedure 2002 was promulgated in December 2002 subsequently amended in June 2003, included procurement on ‘Buy’ and ‘Buy and Make’ through Transfer of Technology (ToT). These categorisations for acquisitions were defined as follows:

- Acquisition covered under the Buy Decision

- Acquisition covered under the Buy and Make Decision

- Acquisition covered under the Make Decision

Acquisition structure (As envisaged by DPP-2002)

Defence Acquisition Council (DAC)

DAC is the highest body headed by the Raksha Mantri (Defence Minister) which oversees the entire acquisition process for the Armed Forces. It approves the long-term perspective plans, the services capital acquisition plans, accords the acceptance of necessity (AON), approves quantity of procurements (QV), categorises the source of procurement and when required nominates the production agency in each case of capital acquisition. Its members include the service chiefs and departmental heads of the Ministry of Defence. The first Defence Acquisition Council was constituted in August, 2001.

Defence Procurement Board (DPB)

The Defence Procurement Board is the Tier II authority which approves the Annual Acquisition Plans and recommends the AON, QV and categorisation of acquisitions related to procurement on capital account. The Defence Secretary is the Chairman of this Board. Its Members include representatives from the various Departments in the Ministry of Defence, the three Wings of the Armed Forces and the Chief of Integrated Defence Staff.

Defence Production Board

Defence Production Board oversees indigenous manufacture and it derives its powers from the direction given by the DAC in respect of the categories of “Make” and “Buy and Make”. It is expected to closely monitor the “make” projects, advise the DAC on policy issues regarding licensed production, ToT and new development projects. Its membership is very similar to the Defence Procurement Board with the exception that the Chairman OFB and some CMDs of the DPSUs are also included.

Defence R&D Board

The Defence R&D Board has been constituted essentially to monitor and report on indigenous R&D proposals flowing out of the “Buy & Make” and “Make” decisions of the DAC. The Chairman of this Board is the Scientific Advisor to RM and Secretary, R&D.

The Acquisition Wing of MoD / DoD

The Acquisition Wing is the main secretariat that provides the necessary inputs to the Defence Procurement Board. This wing is headed by the Director General (Acquisitions) and is assisted by Financial Adviser (Acquisition), Acquisition Managers, Technical Managers and Financial Managers. The Acquisition Wing essentially deals with cases, which have been categorised as “Buy” or “Buy & Make”.

Shortfalls of DPP-2002

Though the DPP-2002 was a major step forward in streamlining defence procurements interactive discussions and consultations between the various stakeholders threw up a series of shortcomings. These included a necessity to compress the acquisition time frame, open tendering for non-sensitive equipment, introduce joint qualitative requirements (QRs) for equipment of tri-services nature, identifying the L1 vendor based on the DCF in multi-currency multi-stage payments scenarios and lack of offsets to leverage benefits from defence acquisitions from foreign OEMs.

DPP-2005

The DPP-2002 (version June 2003) required that the procedure be reviewed every two years. Based on experience gained, suggestions received from Central Vigilance Commission and Comptroller and Auditor General and Ministry of Finance and in order to meet the twin objectives of greater transparency and accountability in all acquisition process and reduction in acquisition time cycle, the government brought forward a new Defence Procurement Procedure 2005 which came into effect from 1st July 2005. Under the DPP-2005 the categorisation of cases was further elaborated as Acquisitions covered under the ‘Buy’ decision, the

‘Buy & Make’ decision (purchase followed by licensed production / indigenous development) and the ‘Make’ decision (indigenous production and research and development). The other salient features of DPP-2005 are removal of the essential and desirable features and making the Staff Requirements more broad-based,

inclusion of offsets, requirement of Integrity Pact, changes in the RFP response process and prescribing a time frame for procurement activities. It also introduced a shipbuilding procedure.

DPP-2006

In the DPP-2006 a noteworthy addition was a procedure for the development of a system based on indigenous research and design categorised as ‘Make’ which provided the requisite framework for increased participation of Indian Industry in the defence sector. Accordingly, the categorisation of capital acquisitions was further detailed as follows:

- Buy Decision: Acquisitions covered under the ‘Buy’ decision. Buy would mean an outright purchase of equipment. Based on the source of procurement, this category would be classified as ‘Buy (Indian)’ and ‘Buy (Global)’. ‘Indian’ would mean Indian vendors only and ‘Global’ would mean foreign as well as Indian vendors. ‘Buy Indian’ must have minimum 30 per cent indigenous content if the systems are being integrated by an Indian vendor.

- ‘Buy & Make’ decision: Acquisitions covered under the ‘Buy & Make’ decision would mean purchase from a foreign vendor followed by licensed production / indigenous manufacture in country.

- Make Decision: Acquisitions covered under the ‘Make’ decision would include high technology complex systems to be designed, developed and produced indigenously.

- Upgrades: All cases involving upgrade to an in-service weapon system

- The major highlights of DPP-2006 were refinements to compress the acquisition procedure further, increasing transparency by listing proposals on the websites, refinement of the field trials procedure, prescribing the offset procedure and establishing of the defence offset facilitation agency and a new fast track procedure that covers acquisitions under ‘Buy’ category or outright purchase.

The underlying principle for formulating a separate procedure for the ‘’Make’’ category of procurements is to enhance the indigenisation component in acquisitions. To genuinely promote indigenous research and development in the defence sector, DPP-2006 provided for cost sharing, normally in the ratio of MoD (80 per cent) and industry (20 per cent).

DPP-2008

The DPP-2008 came into effect from September 01, 2008. Some of the salient features of the DPP-2008 were to provide early information to vendors of impending defence procurements, following up verbal communications with written reports of trials, encoring the Integrity pact on DPSUs and their sub-vendors, vetting of the Staff Requirements by all concerned directorates and promulgating the trial methodology in the RFP itself. Particularly Staff requirements were addressed in detail since it was observed that most proposals had to be retracted either because there were no vendors who met the SRs / Trials or a single vendor situation ensued. Various corrections included posting the RFI on the website, preparation of compliance table of SQRs, vis-à-vis technical parameters of available equipment in as much details as feasible, at the stage of formulation / approval of SQRs, review of reasons for single vendor situation etc. The DPP-2008 delegated financial powers to the Services and the Defence Secretary to approve cases up to Rs 50 crore and Rs 75 crore and also included service officers as Chairman of Contract Negotiation Committees to reduce the workload on the Ministry and fast track approvals. Offsets were also reviewed and the criteria for Indian Offset partner revised, offset banking introduced and fast track acquisitions exempted from offsets.

Subsequently, the 2009 Amendment to DPP-2008 introduced a new category called ‘Buy & Make (Indian)’. Under this new category, Indian companies could partner with foreign OEMs for technical and other production arrangement. The key advantage would be that Indian companies would be the prime contractor and the foreign OEMs were bound to provide technology as mentioned in the Capability Development Document. This was a breakthrough concept that had the potential to transform Indian defence industry provided foreign OEM pressure and the penchant of some services for Buy Global acquisitions could be repulsed.

DPP-2011

The DPP-2011 was introduced in September 2011. The categorisation of the acquisitions was refined and elaborated as follows:

- Acquisitions Covered under the ‘Buy’ Decision: Buy would mean an outright purchase of equipment. Based on the source of procurement, this category would be classified as ‘Buy (Indian)’ and ‘Buy (Global)’. ‘Indian’ would mean Indian vendors only and ‘Global’ would mean foreign as well as Indian vendors.

- Acquisitions Covered under the ‘Buy & Make’ Decision: Acquisitions covered under the ‘Buy & Make’ decision would mean purchase from a foreign vendor followed by licensed production / indigenous manufacture in the country.

- Acquisitions Covered under the ‘Buy & Make (Indian)’ Decision: Acquisitions covered under the ‘Buy & Make (Indian)’ decision would mean purchase from an Indian vendor including an Indian company forming joint venture / establishing production arrangement with OEM followed by licensed production / indigenous manufacture in the country. ‘Buy & Make (Indian)’ must have minimum 50 per cent indigenous content on cost basis.

- Acquisitions Covered under the ‘Make’ Decision: Acquisitions covered under the ‘Make’ decision would include high technology complex systems to be designed, developed and produced indigenously.

Upgrades were retained as hitherto. Other Salient features of DPP-2011 included a further detailing of the Buy and Make Indian procedures, expansion of the hipbuilding procedure to include private sector projects, dilution of the offset requirements to include not just product specific direct offsets but also sector related opportunities in the internal security and civil aerospace sector and a list of eligible offset products and services.

DPrP-2011

Another initiative to make the acquisition process smarter and surer the MoD also issued its first ever Defence Production Policy in January 2011. Though it was an implicit admission of public sector inadequacy, the Policy seeks “to build-up a robust indigenous defence industrial base by proactively encouraging larger involvement of the Indian private sector”. The policy aims at achieving “substantive self-reliance in the design, development and production of (equipment) required for defence in as early a time frame as possible” by creating “an ecosystem conducive for the private industry to take an active role, particularly for small and medium enterprises (SMEs).” The new policy pledges to simplify the “Make” category of the DPP, which makes Indian companies / consortiums compete against each other to develop complex defence systems.

Procedures - a work in progress

Thus, the Defence Procurement Procedure is still a work in progress and is seeing refinement basis, the lessons learnt and the inputs provided by a variety of stakeholders. The key challenge is that every stakeholder in the acquisition business brings his own perspective and interests to the fore. MoD needs to see through these interests and keep the aim of the procedure and the policy directions of the defence production policy foremost whilst contemplating any further revisions. The figure below summarises the evolution process.

Process

This section addresses the procedural issues relating to defence procurement.

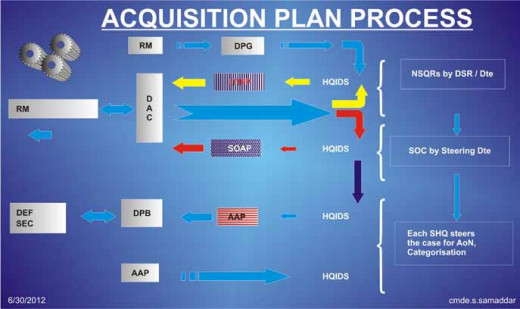

STEA

The basis of all force planning decisions is the Strategic Technological and Environment Assessment (STEA) report. This is prepared by the Headquarters Integrated Defence Staff in coordination with the Services and DRDO.

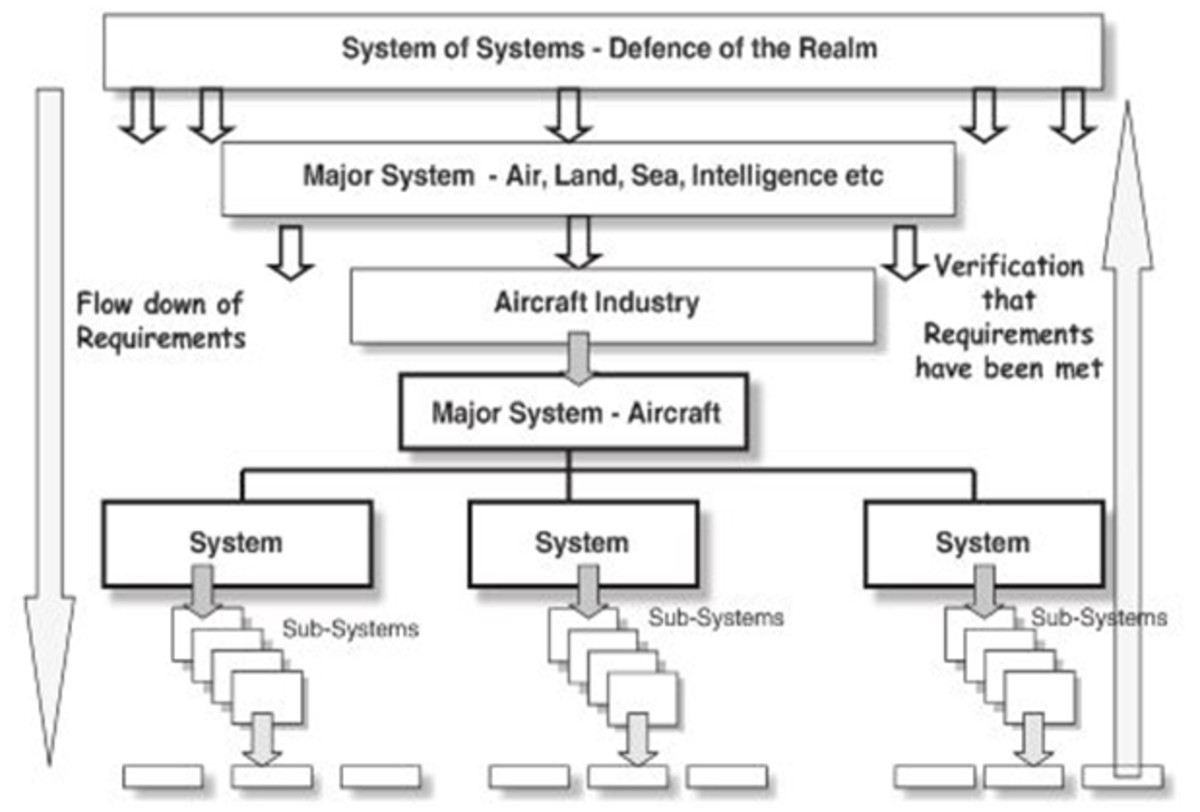

Self-reliance in today’s context means a mixture of global buy and localised “buy or make” decisions at the component, parts and sub-system level of a complete system. This is how major defence systems are planned and executed globally, which can synergise the competitive advantage of each participating partner for the common benefit of reduced costs, faster deliveries and most importantly, superior quality and system performance. Self-reliance is as much an exercise of global strategic sourcing as it is of localising operational facilities of industry / production

The planning system

The output of the STEA report is the preparation of the Defence Planning Guidelines (DPG). On the basis of the DPG, the MoD prepares and approves 15-Year Defence Capability Plan. From the above plan flows 15-Year Long Term Integrated Perspective Plan (LTIPP) for the three services. It is prepared by HQ Integrated Defence Staff in consultation with Service HQ and approved by the Defence Acquisition Council (DAC) under the Defence Minister. 5-Year Services Capital Acquisition Plan (SCAP) is extracted from LTIPP and duly approved by DAC. Both LTIPP and Services Capital Acquisition Plan (SCAP) spell out services’ requirement of equipment in medium and long terms. Based on the SCAP the Annual Acquisition Plans covering a period of two years is then prepared. These are approved by the Defence Procurement Board (DPB). The graphic below depicts the planning process for defence acquisitions.

Foreign Technology Collaboration Agreement provides an opportunity for OEMs and Indian companies to enter into technology Collaboration Agreements under the automatic route

The acquisition process

“Buy” and “Make”

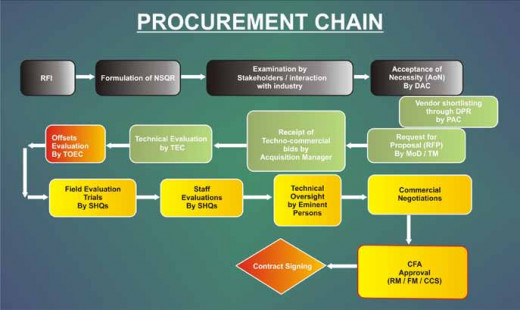

The acquisition procedure differs for “Buy”, “Make” and shipbuilding categories. For the Buy Procedure the following flow chart illustrates the process. Essentially the process comprises the following major milestones as illustrated below:

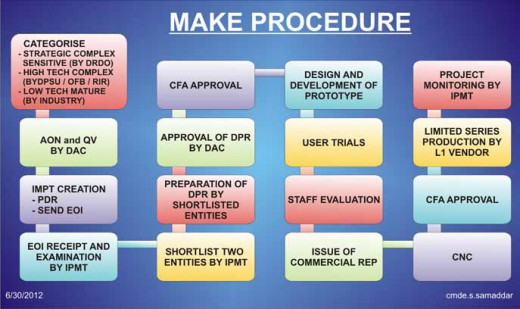

Acquisition process - make procedure

As per DPP-2011 “the acquisition process for this procedure would commence with the issue of Defence Planning Guidelines.” The process is diagrammatically depicted below.

Fast track procedure

Fast Track Procedure for meeting urgent operational requirements was first promulgated vide MoD ID No: 800/SS (A)/2001 dated 28 September 2001. The objective of this procedure is to ensure expeditious procurement for urgent operational requirements foreseen as imminent, or for a situation in which a crisis emerges without prior warning. The acquisition under FTP can be categorised as Procurement of equipment already inducted into Service and Procurement of new equipment.

Practice

Self-reliance

Self-reliance in Defence is of vital importance for both strategic and economic reasons and has therefore been an important guiding principle for the government since Independence. Accordingly, government have, over the years assiduously built-up capabilities in Defence R&D, Ordnance factories and Defence PSUs to provide our Armed Forces with weapons / ammunition / equipment / platforms and systems that they need for the defence of our country. Self-reliance must be the final objective. However, Self-reliance does not mean that every item of a system is sourced only from indigenous vendors. Self-reliance in today’s context means a mixture of global buy and localised “buy or make” decisions at the component, parts and sub-system level of a complete system. This is how major defence systems are planned and executed globally, which can synergise the competitive advantage of each participating partner for the common benefit of reduced costs, faster deliveries and most importantly, superior quality and system performance. Self-reliance is as much an exercise of global strategic sourcing as it is of localising operational facilities of industry / production.

A second model that has been adopted since the beginning of opening up the defence sector has been the licensed production model. In this model, DPSUs were nominated as the licensed production agency for equipment procured from the OEM. From a business point of view of the OEM it is hardly in the interest of the OEM to develop the potential and capacity of the Indian DPSU, accorded the license production, lest it compete with the OEM in future projects. Lessons are evident from the fact that much of the aircraft and military vehicles contracts with DPSUs have not really resulted in an indigenous capability. The recent BEML TATRA case is a concrete example where even the drive system could not be replaced from Right to Left after more than 20 years of service life of the vehicle. Therefore, neither the Joint Venture route or the licensed production route has helped in building the Indian defence industry

Essentially, full systems or platforms are targeted to be delivered by Indian industry. This requires substantial investment in land and equipment, infrastructure and human capital with no guarantee of assured orders by the GoI, which in the case of the DPSU is immaterial. Indigenous design and development for weapons and systems that are sunrise technologies have a substantial lead time and there is no need to shy away from procuring these technologies rather than reinventing the wheel over a period when the technology has moved on and has already matured and newer technologies have arrived. In any event the key differentiator is not technology but basic science and engineering ability.

Instead of developing niche capabilities in sunrise technologies at the component, parts and assembly level on one side and seek to establish a leadership position in system integration on the other side is the mantra for success. The Buy and Make Indian categorisation is the best vehicle to implement such a production policy model since it allows both indigenous sourcing and global procurement but final integration and delivery by the Indian prime.

For Make projects, a new model for indigenous production with Public and Private industries participation simultaneously needs to be considered. Both sectors of Indian industry should be asked to develop a prototype of a new system based on QRs set by the User but within a time frame with well identified milestones and exit options. The selected prototype could be from a PSU or a Private industry or both. Whichever prototype is finally selected, that would then go into production, with the winning proposal being given a 60-75 per cent share and the other participant company a 25-40 per cent share of production. Modalities of such a process should ensure a level playing field for public and private industry.

The defence industrial base is already an MoD responsibility as per Sl 13 and 14 of the Second Schedule of the Allocation of Business Rules for Department of Defence Production. However, based on the complex nature of the subject with multifarious agencies as stakeholders single handedly building a ‘robust indigenous defence industrial base” is a tall order for MoD. The issues and contradictions between the ITC (HS), NIC Codes, SCOMET List, various press notes of DIPP, Formation of JVs and FTCAs, as mentioned above and in addition various issues of indirect taxation such as Customs, Excise and Other taxes and Offset stipulations, requires a larger discussion to truly galvanise the defence industrial base. For instance, on the lines of concessions to SEZs to promote exports the MoD could take

up the case for tax and other concessions for defence industries - however very specifically defined and restricted to licensed companies. For determining the license requirements for entering the defence business a negative list may be more suitable.

An additional issue that impacts the competitiveness of defence procurements is Offsets. The GoI policy that Offsets would be applicable to defence procurements under Buy Global as well as Buy Indian where indigenous content is less than 50 per cent must be supported. However, enabling mechanisms must also be placed in position. Foremost amongst them is the FDI in defence and the FTCA norms, the yardstick for determining indigenous content or value addition by an Indian industry / service partner, whether it is at the parts, components, assembly, services level and how is the content to be measured are metrics that have not been adequately defined. Further, the components of costs that go into a defence product are not elaborated and there is no means of verification whether the claimed 50 per cent

contribution by Indian or Foreign vendors is authentic or not.

Immediate opportunities: An industry perspective

In recent years the mega missed opportunity for growth of a national helicopter building capacity in India in the private sector has been the orders placed for the (80+76) Mi17 helicopters by the IAF without exploring a Buy and Make Indian induction model. Now, the Indian defence industrial base, particularly the aerospace sector, is at an extremely fortunate moment wherein several aerospace projects are under consideration of the Ministry of Defence. Most notable of them are the IAFs AVRO Replacement Project and the C-130J inductions; and, the Indian Navy’s Medium Range Maritime Reconnaissance project, the amphibian aircraft project and the Multi Role Helicopter (NMRH) Projects.

The Indian Air Force (IAF) issued a Global RFI for acquisition of 56 Medium Transport Aircraft in January 2010. This proposal was first shared with Indian Industry on July 1, 2011. During deliberations at MoD, based on the industry presentations prepared by the Industry associations, the MoD it seemed to industry had a sense that the Project would be open to Buy and Make Indian Categorisation, based on the submission of a detailed project report by Indian industries by end October 2011. This would mean Buy 16 aircraft from a Global OEM and Make 40 aircraft by the Indian Partner. Given the SRs there were not more than 3 serious vendors who could offer a fly away aircraft. The total value of the immediate acquisition could be of the order of about US$ 2-3 billion. If we add up the PLM, spares and upgrades over the lifetime of the aircraft - the usual multiplier is 2.5 times - then the programme would be worth about US$ 7-8 billion over about 20 years. The MoD has also indicated that these aircraft may also be considered for the AN-32 replacement programme and can also be exported to other Air Forces. There are additional opportunities for revenues through sales to foreign air forces also. Needless to say maintenance, repair and overhaul would be carried out by Indian industry. Thus a sustainable revenue stream could be generated to make a viable business case for Indian industry to support Buy and Make Indian categorisation.

Going by the available data, precedence and the DPP timelines the anticipated schedule of activities would be that if the Buy and Make Indian categorisation were to be adopted the first “Built in India” aircraft would only be due for delivery after about 7 years from date of award of contract. The common refrain is that Indian industry has no capacity to undertake such an assignment. Of course, this is true and Indian industry will continue to have no capacity unless the opportunity is provided to build this capacity. Not all capacity needs to be built through organic and internal accruals only. Once the potential of the opportunity is identified Indian industry will stream out and look towards inorganic growth through acquisitions of companies abroad, hiring of the best talent for the job at hand from across the world and through them mentoring a tier 2 HR base, expanding the local source base for parts, components and assemblies and so on at a pace no DPSU can match. 7 years is a long time in the private sector to ramp up indigenous capability.

This is a project of strategic importance for the aerospace sector of our country. This project can lay the foundations for a flourishing and genuine indigenous aerospace industry in India of the future. This one project would determine if India is to remain a screwdriver technology nation under the licensed production route or build genuine capability through Joint Ventures / Consortia under the Buy and Make Indian Route with 50 per cent indigenous content and only 10 per cent proprietary technology with OEM.

Going by the discussion and involvement of industry so far the lead players, apart from TATA Group, would be Mahindra & Mahindra and L&T. There are a large number of other players such as GMR, Punj Lloyd, Axis, TAAL etc. who have specific strengths and would partner with the Prime Contractor in some way or the other. In addition, many vendors in the SME segment are already supplying world class products to HAL. Of course, engines would have to be imported but given the numbers creating a final assembly and engine test bed in India, purely as a business proposition is also attractive.

Building IAF Capability alone is not enough - national capacity building ranks higher as a strategic requirement. Therefore a holistic view of the aircraft requirements may be taken. Remembering that Engine costs comprise about 20 per cent of aircraft costs, it is core technology and from a perspective of encouraging an engine manufacturer to locate a manufacturing plant in India we need to look at aircraft acquisitions holistically. The facts are that there are already the C-130Js, inducted and more are on order, the AVRO replacement options being the CASA295 and the SPARTAN 27J, the amphibian aircraft programme of the Navy with the US-2, the Navy’s MRMR programme where the SPARTAN 27J is again a contender. All of them use the same engine or a variant thereof. Going by public domain information the engines to be ordered are more than 400. This is adequate to relocate a manufacturing plant in India. Therefore, categorisation of aircraft induction cases need to be seen in a wider perspective of not just acquisitions but through which service capability, lowered life cycle costs and most importantly national capacity are built. If there is an additional cost or single vendor situations then it must be balanced against the national capacity being built and after due checks and balances the appropriate decision in the overall national interest taken. Single vendor acquisitions are possible under the DPP-2011 and these provisions must be utilised if they build a national capacity.

The government must come forward and demand that Indian industry undertake this project and if concessions and incentives are required to make the project see the light of day then those must be made available in the national interest. For no other reason than pure legitimacy of the conflicting positions all that the IAF has to do is to issue a Capability Definition Document to the large industrial houses and seek a written Detailed Project Report. This report once evaluated by an unbiased committee can draw its own conclusion about whether Indian industry can or better has a well defined road map to deliver on the project. In any event the IAF is not the authority to certify the capability or otherwise of the Indian industry and they can well learn some easy lessons from the Indian Navy which has trusted Indian industry to build first class warships and submarines in India. It would be real shames to the IAF were the Navy to categorise the much more sophisticated Multi Role Helicopter (MRH) project for acquisition under the Buy and Make Indian categorisation.

Regrettably the Defence Acquisition Council in its meeting of July 24, 2012 categorised the Rs 12,000 crore project as Buy Global with 16 aircraft delivered on “fly away condition” the next 16 to have an indigenous component of 30 per cent and the balance 24 with 60 per cent indigenous content. In other words, by cost the OEM would get a share of (16+70 per cent x 16+40 per cent x 24) 36 aircraft and the Indian partner 20 aircraft. The Global OEM is to identify an Indian partner - a pretty tough task as the business proposition for an Indian company, to be interested, is unattractive. As any aircraft manufacturer can understand, including the HAL, obtaining 60 per cent indigenous content in a transport aircraft is close to impossible, unless a prohibitive cost is paid.

The Navy’s MRH project is the second and possibly final opportunity for Indian Private sector defence industry to build an alternative and highly sophisticated helicopter building facility in India. As per the RFI issued for this project almost a 100 helicopters are to be acquired by the Indian Navy for multi-role requirements. The contenders are possibly limited to at the most three vendors. The numbers are attractive for Indian industry and the project itself may be of the order of US$ 10-12 billion and another US$ 15 billion for maintenance, repair and overhaul over the next 25 years. The helicopters also have potential civil and commercial applications.

The note that Offsets will build Indian industry is false since by definition offsets utilise only existing capabilities and thus do not nurture growth. Offsets can never build capability since Indian vendors will remain subsidiary to foreign primes. Similarly, licensed production has been a bane to Indian industry and is a luxury business model that only DPSUs can adopt since there is no visibility post the licensed numbers have been delivered. The chart below depicts the deficiencies in following the licensed production route. The key differentiator is that in Buy and Make Indian projects Indian companies dictate the terms whilst in Buy Global and Licensed production cases the foreign OEM is supreme. It does not make any business sense for the OEM to empower his Indian partner with such capability that it may become its own competition in the future. It also does not make any business sense to the foreign OEM to encourage import substitution since every such substitution results in lower revenues for itself. The Su-30 and the AJT are examples of licensed production in India the success or lack of it, in these projects building genuine capability in India, is clearly evident. It is also evident that LP can only be supported by DPSUs where financial feasibility is never a consideration. The private sector would model a business case quite differently.

The MoD has also taken some brave baby steps in opening up complex projects under the Make category to the private sector. Of particular note are the Tactical Communications System (TCS) and the Future Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) projects. For the TCS project two contenders, a consortium of Larsen & Toubro, Tata Power SED and HCL Infosystems Ltd and Bharat Electronics Limited, are in contention for the Indian Army’s Tactical Communications Systems (TCS) Project. The project is worth Rs 10,000 crore. This is the first project under the ‘Buy Indian, Make Indian’ clause introduced in the Defence Procurement Policy (DPP) 2011. The FICV is by far India’s biggest-ever land systems contract, for production of 2,600 FICVs to replace ageing BMP-2 vehicles. In a four corner contest only two companies would be down selected as “Development Agencies,” who will each design and build a prototype of the futuristic vehicle. The final design would be selected after trials. In both projects bulk of the development cost would be borne by the MoD. These projects will genuinely build Indian defence industry and such projects must find greater encouragement for categorisation as make projects.

Finally, we need to understand that in practice the human resource base to genuinely develop the Indian Defence industrial complex is minimal. Not enough interest exists in this strategic sector and the academic institutions are not yet up to speed in having the right infrastructure and tutors / mentors to take the education campaign forward. This is an area where the DRDO has to work with the IITs / NITs to develop the right faculty and the lab and test facilities to bring up the HR base in this country. Secondly, acquisitions are a matter of complex study and expertise. At the moment this is being undertaken by tenure based generalists from the armed forces and the civil services. It needs no emphasis that these sub-optimal and acquisition projects worth US$ 250 billion cannot be left to the good sense of tenure bureaucrats and service officers. We can have the best procedure but ultimately that procedure has to be executed by humans and quite obviously talent and skill can make or break these projects.

Factor

| Licensed Production Model as (Buy and Make with ToT)

| JV / Sub-contract Model (Buy and Make Indian)

|

|---|---|---|

Prime Contractor

| OEM

| Indian JV / SPV

|

Accountability for Product Support

| OEM

| Indian JV/ SPV

|

National Vision

| Short Term – no capacity building as driven partner

| Long Term – genuine capacity building through participation as driving partner

|

Business Model

| Royalty and License Fee

| Joint Revenue Generation for Growth and profit sharing through dividends with investments

|

Termination

| One Off and at discretion of OEM

| Not possible due contractual and business commitments

|

Brand Ownership

| OEM

| Joint with Indian Industry Partner (IIP)

|

Valuation

| As an OEM Product. “Manufactured Under license from OEM”

| Branded as a Joint “OEM-IIP” Product

|

Sustenance

| Short and dependent upon Product life cycle

| Longer sustenance and for more products, including Design and Engineering to meet India specific requirements

|

Relationship

| Confined and limited to immediate Business opportunity on pure financial terms

| Larger and more comprehensive, stable and sustained relationship

|

Indigenisation

| No scope as LP may be competitor to OEM. Offsets may not go to LP. ToT extremely limited and contractually driven

| 50 per cent indigenous content and in the interest of both companies to be cost and technologically competitive to do utmost to reduce production cost and increase technical features for second sale to exiting customer or open new markets

|

Precedence

| Su30MK; AJT

| LPD: Radars for the Indian Navy

|

Conclusion

These policy guidelines are a novel initiative in capturing the requirements of the services and industry to work together in creating a defence industrial complex that India can be proud of. As the MoD and the Hon’ble Raksha Mantri have stated in several forums transparency together with expeditious procurement is the mantra to equip our armed forces with the best possible equipment. Towards adhering to transparency the DAC / DPB Agenda and minutes should be placed on the MoD website just as is the case with DIPP and FIPB. The Buy and Make Procedure allows the best chances for expeditious procurement since this system alone ensures that only technically qualified vendors are shortlisted even before the RFP is issued.

The way forward is to promote the Buy and Make Indian procedure to be the default procedure. Buy Global acquisitions should be the last resort as the MoD and the Indian regulatory framework leak like a sieve in the monitoring of offset contracts and no real capacity is being built through this process. On the other hand, foreign OEMs will have no choice but to engage with Indian industry, both DPSU and Private, to win projects in India. Since these are competitive no Indian Prime will ever accept loading the commercials with ToT costs as that would be lose-lose for both foreign OEM and Indian Prime. Therefore, the Non-recurring Expenditure burden would have to be mostly borne by the foreign OEM and hence the induction of technology would be cheaper and faster. Forming JVs with Indian partners will build Indian capacity and open the route for India to become part of the global supply chain for the aerospace and defence industry. This would also promote Indian industry to innovate, something it cannot do as a mere offset partner.

Article By Team

- Defence and Security Alert

Defence and Security News Magazine in India by Defence and Security Alert (DSA) - Committed to Defence and Security Worldwide.