Definition of Patent

In the United States, a patent is a property right granted by the federal government to an inventor "to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States or importing the invention into the United States" for a limited time in exchange for public disclosure of the invention. Parsing this definition of a patent is instructive.

Note: The author is a retired patent attorney who spent 15 years helping his corporate clients protect their intellectual property.

"A Property Right"

Property rights are laws created by governments that define how owners can control, benefit from and transfer their property. By having strong property rights, governments encourage the creation of wealth because people work harder to generate new property when they know their property will be protected from unlawful use by others. In the United States, Congress has created patent laws that define how inventors can control, benefit from and transfer their inventions. These laws have encouraged Americans to make new inventions.

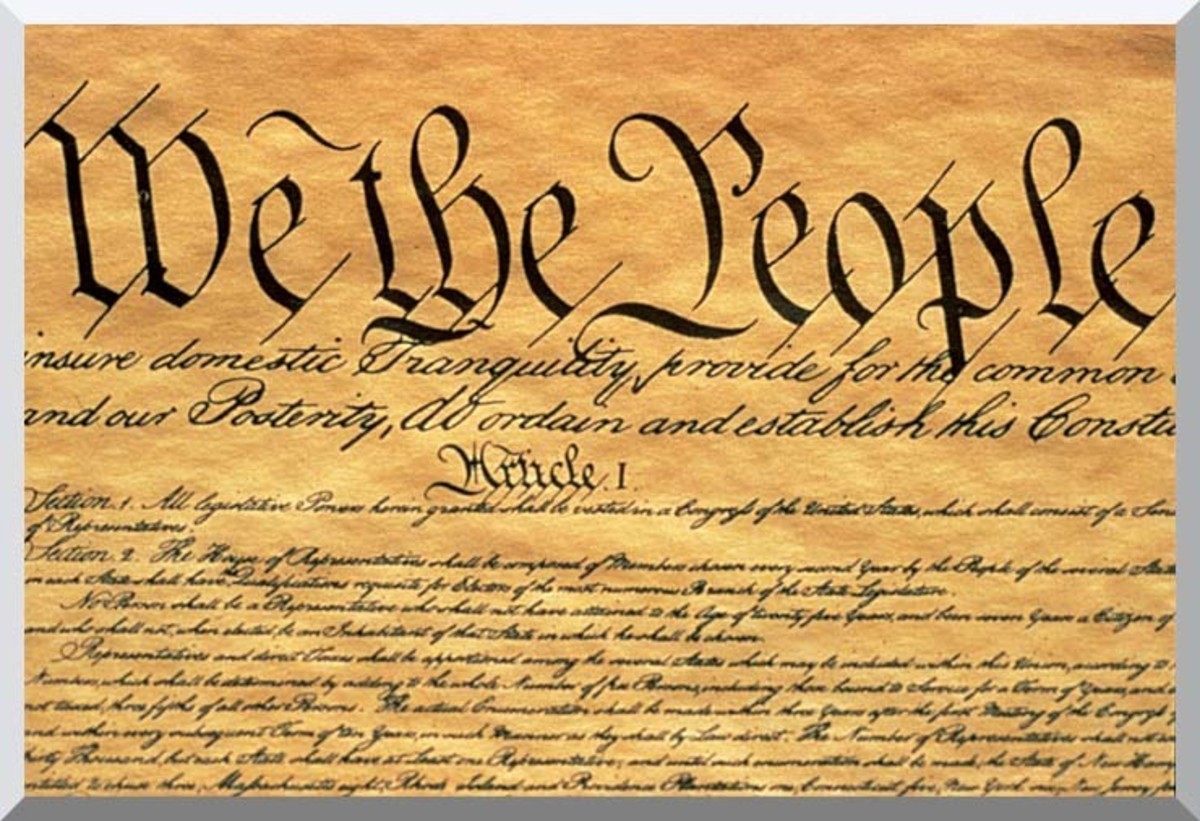

"Granted by the Federal Government"

In the United States, only the federal government has the power to grant patents. This power was assigned to the federal government by the U.S. Constitution, and any attempt by one of the 50 States to grant a patent would be pre-empted.

Inventorship Hypothetical

Assume A conceives of an inventive machine, and B conceives of a feature for that machine. A and B instruct C to build a prototype using A and B's blueprints. In this example, A and B are co-inventors of a patent claiming A's machine with B's feature, while C is not an inventor because he only helped A and B reduce their invention to practice without making any mental contribution.

"To an Inventor"

Patents are granted to the inventor. The inventor is the person who conceived of an invention. Multiple people can be co-inventors, as long as each contributed towards the conception of the invention and they collaborated. A person who merely helped implement an invention at the inventor's instructions is not an inventor. The inventor can sell (i.e., assign) his rights in the patent to another party. The assignment must be in writing. Employers usually require their employees to agree to assign any patented inventions they might make during the course of their employment to the employers as a condition of employment.

Exclusion Hypothetical

Assume X owns a patent on ice cream. After Y buys ice cream from X, he adds bananas to create a banana split, which he patents. When Y opens a store where he makes his own ice cream and uses it to sell banana splits, X sues for patent infringement. Y's defense is he's only practicing his own patented invention. Will Y win? No. Y's patent does not give him the right to do anything. It does not even give him the right to make the banana splits he invented! In contrast, X's patent gives him the right to exclude others from making ice cream. Thus, he can stop Y from selling his banana splits.

"To Exclude Others"

A patent does not give its owner the right to do anything. Rather, a patent gives its owner the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing the patented invention.

The exclusionary nature of patent rights is widely misunderstood. There have been situations where a company spends good money to buy a patent from another party based on plans to make and sell a product incorporating the patented invention only to learn they cannot actually sell that product because doing so would infringe on somebody else's patent rights.

"From Making, Using, Offering for Sale ... Selling ... or Importing"

A patent is a piece of intangible property giving its owner a bundle of rights for the invention covered by the patent, including:

• the right to exclude others from making the invention;

• the right to exclude others from using the invention;

• the right to exclude others from offering for sale the invention;

• the right to exclude others from selling the invention; and

• the right to exclude others from importing the invention.

These rights are independent. For example, a patent owner can allow one company to make the invention and another company to import the invention.

United States Hypothetical

Assume M owns a U.S. patent on an invention used in a phone. N opens a factory in France to manufacture a competing phone which uses the patented invention. N's manufacturing does not infringe M's U.S. patent since it occurs outside the United States. M would need to obtain a French patent to stop N's manufacturing. But if N starts to import its phones into the U.S., then M could use its U.S. patent to stop the imports.

"Throughout the United States ... or ... Into the United States"

Patents are territorial since they are property rights granted by a sovereign government. Thus, for example, the rights granted by the U.S. government for U.S. patents apply to activities with a connection to the United States, such as making the invention in the United States or importing the invention into the United States. Patents granted by other sovereigns are similar.

Invention Hypothetical

Assume a U.S. patent shows a diagram of a cell phone on its cover sheet, and 100 pages of text and 20 drawings describing the phone's complicated electronics. It also includes a single sentence describing a touch screen. If the patent's only claim reads "A cell phone, comprising: electronics; and a touch screen coupled to the electronics", then the "invention" covers a cell phone with a touch screen. This patent would not cover a competing cell phone that copies the complicated electronics if that phone does not also have a touch screen.

"The Invention"

The "invention" covered by the patent is defined by one or more claims appearing at the end of the patent. Just as a deed defines the metes and bounds of a piece of land, the claims define the metes and bounds of a patent. The interpretation of a patent's claims requires a careful review of the patent's specification, drawings, claims and prosecution history in light of the prior art. This interpretation is often a complex exercise performed by a patent attorney.

Limited Time Hypothetical

If a patent issued on June 1, 2010 from an application filed on July 1, 2007, its term will end on July 1, 2027 provided all of its maintenance fees are paid on time. If the July 1, 2007 application claimed priority from a non-provisional application filed on May 1, 2005, then its term will end on May 1, 2025.

"For a Limited Time"

Under current law, the term of a U.S. patent is 20 years from the earliest U.S. application (except provisionals) from which priority is claimed. However, if the application was pending or the patent was in force on June 8, 1995, the term is the longer of 17 years from the issue date or 20 years from the filing date of the earliest U.S. or PCT application (excluding provisionals) from which priority is claimed. Patents expire earlier if their maintenance fees are not paid on time.

The exception is design patents, which have a term of 14 years from issuance.

Public Disclosure Hypothetical

Assume an inventor applies for a patent for his new recipe for chocolate chip cookies. However, in order to maintain a competitive advantage over anyone who might use his recipe, he fails to describe a special ingredient that makes his cookies taste better. Result? The patent will be invalid because the inventor failed to disclose his best mode for making the cookies. Since he failed to uphold his end of the contract, the government will not grant him monopoly rights.

"In Exchange for Public Disclosure of the Invention"

A patent is a contract between the inventor and the government. The inventor agrees to describe his invention to the public in exchange for the government's grant of monopoly rights. The inventor benefits from the exclusive rights, and the public benefits by being taught the details of the invention. In the application for a patent in the United States, the inventor must provide a written description of the invention, must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the invention, and must describe the best mode of which he's aware for practicing the invention.

Disclaimer: The author has retired from the practice of law. This cursory article is for information purposes only, is not legal advice, and does not establish any attorney-client relationship. The author encourages any reader with questions about patents to contact an attorney.