Pricing Products: Four Major External Considerations

There are many factors external to a company that influence, greatly, what price will be attractive enough to entice interested buyers. Factors related to internal costs (fixed and variable) should always set the lower limits of pricing decisions, but external forces, including market and consumer demand, should set the upper limits.

Consumer, business, and industrial buyers all must weigh the price charged for a product or service against the benefits that ownership will deliver. In other words, a seller's freedom to set prices varies, and it is limited externally by circumstances present in the type of market in which the offering is being made.

In this article, I will examine major external variables that must be considered when making pricing decisions, including:

- Different types of markets

- Consumer price sensitivity

- Pricing strategies driven by consumers and competitors

- Other important economic variables

Pricing in Different Types of Markets

The seller’s pricing freedom varies with different types of markets. If there were such as thing as "pure competition," the market would comprise many buyers and sellers trading in a commodity of uniform quality (sugar, wheat, crude oil, soybeans, copper, iron ore, etc.). In such a market, no single buyer or seller would have much effect on prevailing market prices.

In a market characterized by "monopolistic competition," every company has at least some monopolistic power, because every company is free to set its own price. There are many buyers and sellers, and no single market price. Because of product differentiation (which may be marginal--toothpaste, is a good example), companies can differentiate their offers to buyers, giving the seller some degree of control over price setting. This type of competition is believed by many to be the best form, because it combines ideals of perfect competition with the best characteristics of a monopoly.

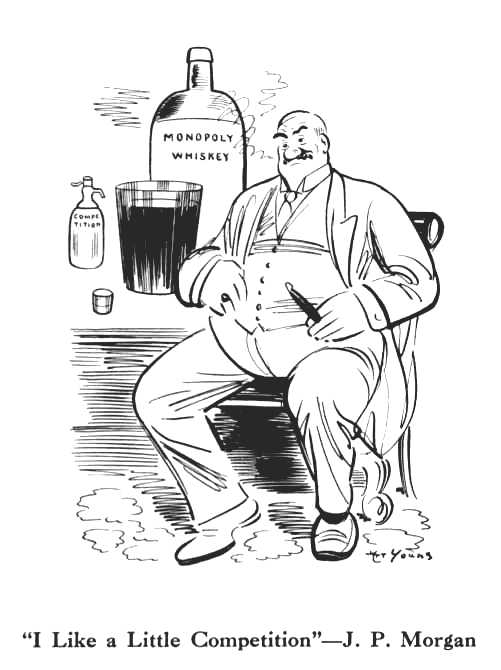

In a pure monopoly, there is just one seller. A regulated monopoly is under government control, and, as a company, is permitted to set prices allowing a fair return on investments. But, when a monopoly is not regulated, the company is free to set its prices levels based on what a market will bear. Pricing decisions are still made with care, however, for a number of reasons, including fear of government control, speed at which a market is penetrated, and not wanting to attract the attention of potential competitors.

In markets ruled by "oligopolistic competition," there are a few powerful sellers dominating the market, although there can be lots of small companies also operating in it as well. The major market share is split among dominating firms, and it is difficult for new companies to enter the market. The airline and petroleum industries provide good examples of oligopolistic competition.

In such markets, key competitors control scarce resources, there are high advertising/promotion (due to strong brands/loyalty), R&D, and set-up costs. These things create great barriers to entry and delays in the ability to start earning profits for the firms that do manage to enter the market. Predatory (deliberately lowering prices) and limit pricing (low price, high volume output) practices are also used, sometimes, to force rivals out of the market, and/or to discourage new entrants.

Ultimately, sellers in all market types must be "buyer oriented" when making pricing decisions. The ultimate consumer of the product/service will make the final determination about what pricing level is acceptable for each market offering.

Consumer Price Sensivity

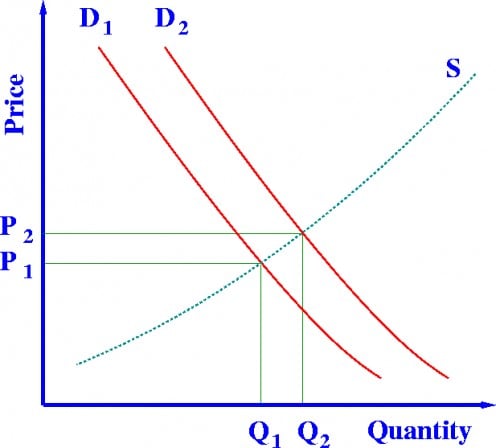

Every price a company might charge for a market offering will lead to a different level of consumer demand. The problem for marketers is to figure out how much effect a change in price might have on demand for a particular product or service.

Usually, demand and price have an "inverse" relationship. Raising price usually lowers demand, and raising demand usually lowers prices, except in the case of what is called "prestige" products and services. When it comes to market offerings with a "prestige" cachet, raising prices can also raise demand. With many of these products/services, the more things cost, up to a point, the more prestigious they are (designer handbags are a good example of this). With these market offerings, the normal demand/price relationship does not apply. But, if prices become too high, even with prestige pricing, there will eventually be a decrease in demand.

It is important for marketers to learn as much as possible about price elasticity. How responsive will consumers in your industry be to changes in price? To provide a foundation for answering this question, let's take a look, using the following table, at what things can determine or influence the price elasticity of consumer demand.

Levels of Consumer Price Sensitivity

When the product/service is:

| Buyers are usually:

|

|---|---|

Unique, high quality, prestigious, or exclusive

| Less price sensitive

|

Hard to find

| Less price sensitive

|

Cannot easily compare the quality of subsititutes for the product/service.

| Less price sensitive

|

Everyday, mundane, similar in quality across the board

| More price sensitive

|

Easy to find, carried by many different retailers

| More price sensitive

|

Easy to find and compare prices/quality of substitutes for the market offerings

| More price sensitive

|

Pricing Strategies Driven By Consumers and Competitors

Ultimately, a company's approach to pricing will be based on either costs or value. Internally driven, cost-based pricing is focused on what it takes to recover the cost of producing, distributing, and promoting the product, before profit can be made. Externally driven, value-based pricing is the exact opposite. It uses customer perceptions of product value to set its target price.

Consumer Perceptions

Value-based pricing uses buyers’ perceptions of value, not the seller’s cost, as the key to pricing. Value-based pricing means that the marketer cannot design a product and marketing program and then set the price. Price is considered along with other marketing mix variables before the marketing program is set. When using value-based approaches, pricing setting begins with analyzing consumer needs and value perceptions with regard to the product/service. Then, price is set to match consumers’ perceived value.

A company using value-based pricing must find out what value buyers assign to different competitive offers. Measuring perceived value can be difficult. Sometimes, companies ask consumers how much they would pay for a basic product and for each benefit added to the offer. Or, a company might conduct experiments to test the perceived value of different product offers.

More and more, marketers have adopted value pricing strategies—offering just the right combination of quality and good service at a fair price. In many cases, this has involved introducing less expensive versions of established, name-brand products.

If demand is elastic, rather than inelastic, sellers will consider lowering their prices.

In setting its prices, the company must also consider competitor’s costs and prices and possible competitor reactions to the company’s own pricing moves.

Value-based pricing approaches help the company to flex its pricing muscle. That is, it allows a company a certain amount of freedom from price competition wars with competitors, because it provides a way to justify setting higher prices and margins, without losing market share. Instead of focusing or competing strictly on price, it attempts to build the value of market offering. This sometimes calls for "value-adding" strategies that help to differentiate one product/service from competitive market offerings. Once value is added, in the eyes of the consumer, price is no longer the only thing differentiating one offer from another. That means a company's product/service is not simply competing on price, and the offer can sustain higher margins.

EDLP (Every Day Low Pricing)

At the retail level, an important type of value pricing is called "everyday low pricing (EDLP). This pricing approach involves charging, every day, a constant low price, allowing for none or few temporary price discounts. Giant retailer, Wal-Mart, uses (and practically "owns") this concept. EDLP is in direct contrast to the high-low approach used by many retailers. In high-low pricing, a retailer charges higher prices daily, but runs frequent promotions lowering prices on specific items, temporarily.

Competition-Based Pricing

One form of competition-based pricing is going-rate pricing, in which a firm bases its price largely on competitor’s prices, with less attention paid to its own costs or demand. The firm might charge the same as, more than, or less than its major competitors. For example, in oligopolistic industries that sell a commodity such as steel, paper, or fertilizer, firms normally charge the same price. The smaller firms simply follow the leader.

Competition-based pricing is also used when firms bid for jobs. Using sealed-bid pricing, a company bases its price on how it thinks competitors will price rather than on its own costs or on consumer demand. The firm wants to win a contract, and winning the contract requires pricing at levels that are less than what other firms will charge.

Other Important Economic Considerations

Many things going on in the economy can exert a strong impact on a company's pricing strategies. Since economic conditions will affect the strategies of other players in the distribution channels, a firm has to make pricing decisions while keeping in mind things that might involve/affect others (such as retailers, wholesalers, governmental policies, and social concerns).

Governmental policies, and the potential for government intervention, for example, can affect price floors in the interest of borrowers and sellers. In addition, the costs of raw materials, competitors' prices, and consumer demand relative to supply are factors external to the control of companies that must be taken into consideration.

During tough economic times, such as recessions and/or periods of high unemployment, consumers will spend less and demand lower prices. Times such as these usually mean sellers must lower prices in order to entice consumers to purchase.

The ultimate pricing decisions a company makes will fall somewhere between being too low to produce a profit and too high to produce demand. The lower limit for pricing decisions will be set based on what it costs to produce/deliver the product, and the upper limit of price, on consumer's perceptions of the product’s value. Placed firmly between these two extremes are competitor’s prices and other external and internal factors. The company must take all these things into consideration as it seeks to find the best price.

The Author

Dr. Middlebrook is a former college professor of marketing and mass communications. She spent nearly twenty years behind the desk teaching courses in advertising, marketing, public relations, and journalism. In addition, she worked, for many years, as a consultant and as an employee in corporate marketing and communications.

This article is a companion to another I created that examines internal considerations companies need to be concerned about, and to look at, before making pricing decisions.

© 2013 Sallie B Middlebrook PhD