An Overview of Australian Labor Regulation

I. Introduction

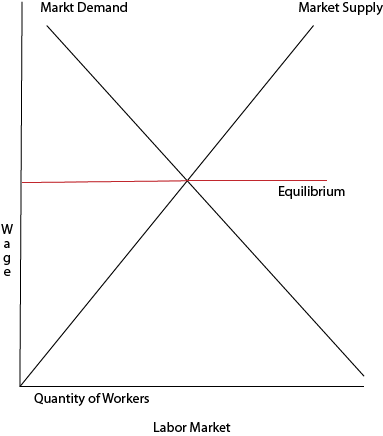

The labour market composed of supply and demand components. On one hand, the supply side encompasses potential workers who are willing to provide their labour, knowledge, time and skills. The differences among different types of labour are determined by the differences in their inherent capability, education, training and other market influences (Acemoglu, 2002). On the other hand, the demand side includes employers and their corresponding job requirements. Like other types of markets, legislation and regulations are needed to facilitate the exchange and alleviate market inefficiencies. However, unlike other markets of goods or materials, the nature of the labour market can be quite sophisticated and intricate since people are the product traded on the market (Mortensen, 1986). Human capital is one of the three most important factors in production – land, human and capital –, and it is a highly valuable goods because it contributes to firm’s profitability (Robbins & Coulter, 2012).

In Australia, throughout the history of the Australian industrial system, various forms of protection have been set up by the government in terms of minimum standards to protect the workers, who are often considered the vulnerable with little or no bargaining powers as compared to their employers and thus are in need of help and support from the state. Some examples can include minimum wages, unionism, minimum safety standards, agreements such as 'no disadvantage' or 'better off overall test' (BOOT) for workers, etc (Naughton & Pittard, 2013). Some exemplary statutes designed specifically to protect and ensure fair treatment and minimum protection for workers in Australia are Anti-Discrimination Act (NSW) 1977, Sex Discrimination Act (Cth) 1984, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act (Cth) 1986, Fair Work Act 2009, Independent Contractors Act 2006, Occupational Health and Safety Act (NSW) 2000, Fair Work Act 2009, etc.

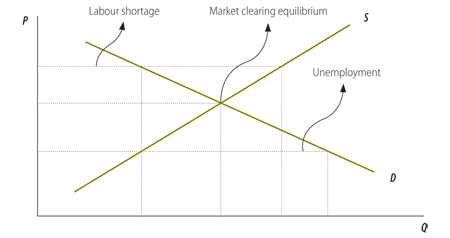

Ever since Adam Smith coined the term “the invisible hand” in his famous book “The wealth of nations” referring to the idea that the market has its own mechanisms to adjust the use and allocation of resources, interference with the market’s operation by the government’s rules and regulation has been frown upon (Smith, 1776). On the one hand, it is argued that since regulations in the labour market were associated with higher unemployment rate and lower workforce participation rate, it is better not to meddle with the free market (Botero, et al., 2004; Besley & Burgess, 2004). On the other hand, it is also disputed that labour market regulations are necessitated in a world where conditions were unfavourable to workers; hence, to protect their well-being and enable smooth workflow, some degree of regulations needs to be put in place (Campell, 1998; Gordon, 2014). In this essay, I would like to make the case that although labour market regulation does affect economic performance, it is necessary to maintain some levels of legislation in the labour market to maximise the economic outcomes.

II. Overview of Australia’s current legal labour framework

As in many other countries, Australian labour law originated from the common law, in which the relationship between the workers and firms are managed through a complicated framework of statutes and regulations, consisting of legislation, regulations and industrial instruments such as awards and corporate agreements. Over the years, reforms have been made to these sets of rules and regulations to better address the development of Australian labour market. Irrespective of these changes, Australian labour laws help to protect the employee and impose significant legal obligations on employers (Stewart, 2015).

In 2009, the Fair Works Act replaced the Workplace Relation Amendments Act and became the main guiding statute for the labour regulation in Australia. The Fair Works Act lays out some minimum entitlements which employers must meet for the sake of their employees including maximum hours of work (no more than 38 hours per week plus reasonable overtime hours), annual leave, personal leave, parental leave (12 months unpaid parental leave), community service leave, flexible work arrangements, public holidays, notice of termination and redundancy pay, and fair Work Information Statement. Failure to comply with the National Employment Standards violates the Fair Work Act and can lead to penalties of up to AUD51,000 per violation and other potential punishment. The National Employment Standards stipulated by Fair Works Act inherits on the Workplace Relation Amendments Act and some components of traditional Australian work values and labour rights while includes some advanced features such as a modern award system (Pittard, 2011). The Acts provides a safety net for workers within the context of increasing globalisation although it still runs the risk of becoming quickly outdated (Murray & Owens, 2009). In addition, employers and employees can negotiate collectively for an enterprise agreement which provides for terms and conditions exceeding the minimum terms and conditions of employment required by the state government.

III. The necessity of regulation in stipulating minimum labour standards

If the market conditions are perfect, i.e. firms and workers are completely free to enter and exit these markets, free market is the most effective mechanism to allocate workers and their wages. This argument is based on Adam Smith’s invisible hand theory which states that when individuals seek to maximise their own interests, they also maximise the society’s interests. This implies that any interference of the government with the free competitive labour markets will distort the market signals of price and produce a less optimal outcome (Borjas, 2016). Unfortunately, there exist several inherent inefficiencies in the labour market.

First, the labour market is rife with asymmetric information which leads to adverse selection on market. In order to ensure market efficiency, it is necessary that all employers know the true quality of a potential employee, and all job seekers know all available job opportunities. When these conditions are not met, adverse selection happens, causing the labour market to collapse (Özdurak, 2006).

Second, political interests can interfere with market operation. It is argued that political parties are subject to and respond to the demand of their voters. Once the party is elected and in charge of the government, it has the authority to determine government spending, labour regulation, types of unemployment benefits, and other related labour issues. For instance, a study by Lucifora and Moriconi (2012) reveals significant evidence that political turnover and political polarization are correlated with a more heavily regulated labour market, lower unemployment benefit replacement rates, and a smaller tax break on labour.

Third, the very existence of externalities casts doubt on the idea of letting the market alone rule the labour market. For example, it can be argued that low level of education and training of labour force creates negative externalities, thus, government’s intervention is called for to mitigate the situation (Acemoglu & Angrist, 2000).

In short, under perfect market conditions, free market is the best tool to mediate the labour market. However, because of market anomalies, government interference through legislation, regulation and other fiscal policy might be necessary to achieve certain stabilising goals.

IV. The mechanisms of regulation in maintaining minimum labour standards

With its current framework, Australian labour law can guarantee minimum protection for employees through various mechanisms. First, the labour law created an effective award system to set a universal floor ascertaining that the minimum needs such as food, shelters, etc. for employees are covered. Awards are extended beyond just minimum wages, but also includes matters such as working hours, working schedules, breaks, and allowances. These regulations protect employees’ security by restricting the ability of employers to under-compensate workers or by making dismissal costly. An analysis by Pittard and Naughton (2013) stated that:

The new-style awards are no longer the outcome of an adversary process. Modern award making is a 'top down process', where a Full Bench of FWC is given the taskof developing an award framework, which together with the NES constitutes a safetynet of terms and conditions.

The award minimum standards were decided through an intensive process involving the negotiation between employers, unions and government, and other relevant parties, and the final determination was by the independent statutory body. It also made it illegal if these minimum pay and conditions are overwritten by agreement of the parties. However, one criticism against the award system is that it makes labour become costlier, increasing the non-wage labour costs of employers. For example, employing three different state panels of administrative employment data, Meer and West (2013) found that minimum wages significantly impede job growth with employers trying to take advantage of their current employees rather than hiring new ones. The negative impacts are particularly more pronounced regarding new job creation for younger workers (Meer & West, 2013). Furthermore, after investigating the relationship between formal qualifications, job roles and pay rates in Australia’s modern awards, Oliver and Walpole (2015) criticise that since the relationship between qualifications and award is rather weak, especially across industries, the current award system in Australia does not promote further skills attainment among most of the award-dependent workforce.

Second, regulations oversee the formations of various unions, coalitions or organisations that can enhance the collective bargaining powers of workers. Among those parties, unions can be considered one of the most powerful organisations. Unions were first established in Australia by free works at the beginning of the 19th century. With the foundation of the Australian Council of Trade Unions in 1927 and the creation of the arbitration system, unions gain their popularity and members among Australian workers. The unions have empowered workers to obtain various achievement such as lower work hours, equal pay, gender equality, and immigrant protection, etc (Bramble, 2008). Moreover, unions also facilitate the monitoring and enforcement of compliance with minimum standards. Enforcement strategies adopted by unions include direct dealing with employers such as negotiation, formal use of the legal system, provision of education and information to workers, public ‘naming and shaming’ of non-cooperative employers, industrial action, and other forms of available leverage or pressure(Landau, et al., 2014).While reviewing the roles of non-state actors in imposing the minimum labour standard, Hardy (2011) argues that trade unions can be very effective in pushing employers to comply with labour standards due to their prevalent presence in workplaces (as indicated by their number of members, delegates and organisers), their relative independence from employers, and experience in understanding the nature of issues of a particular organisation or industry. Nonetheless, unionisation poses the threats of decreasing profitability for company, thus in turn hindering investment and lowering employment (Hirsch, 2003). Unionism is also deemed to correlate negatively to economic growth (Pantuosco & Seyfried, 2008).

Third, the government also has punitive, enforcement and compliance measures to punish non-compliance behaviours. For instance, in recent years, enforceable undertakings, which refer to legally binding agreement between the relevant authority and proposed company, have also become a commonly-used measure by the authority. According to Hardy and Howe (2013), through enforceable undertakings, there are three stages to reaching long-lasting corporate compliance:

First is management commitment to comply - which itself is frequently prompted only by the shock of the crisis of enforcement. The second stage is learning how to comply - often by appointing a person at a high level in the organisation to be responsible for implementing and operating a compliance programme. The third stage is the ongoing institutionalisation of compliance in everyday operating procedures and corporate culture.

Although some praised enforceable undertakings as a feasible alternative to traditional punishment measures, other critics raise concerns regarding the accountability and effectiveness of this enforcement tool (Hardy & Howe, 2013).

Does your workplace unionise?

V. Conclusion

In conclusion, due to the complex nature of the labour market, in addition to free market mechanisms, government regulations are needed to ensure minimum labour standards to protect the vulnerable workers. However, there are always tensions influencing governmental enforcement of such standards between government and employers, and between the main political parties over industrial and economic issues (Goodwin & Maconachie, 2011). In addition, as described, there is no perfect regulation solution, and each solution has its own advantages and disadvantages. Hence, it is recommended that the government acts with caution when interfering with the market mechanisms.

What is the Fair Work Commission?

References

Acemoglu, D., 2002. Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(1), pp. 7-72.

Acemoglu, D. & Angrist, J., 2000. How Large Are Human-Capital Externalities? Evidence from Compulsory Schooling Laws. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, Volume 15, pp. 9-59.

Besley, T. & Burgess, R., 2004. Can Labour Regulation Hinder Economic Performance? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, p. 91–134.

Borjas, G., 2016. Labor Market. 7th ed. s.l.:McGraw-Hill.

Botero, J. et al., 2004. The Regulation of Labor. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4), pp. 339-1382.

Bramble, T., 2008. Trade Unionism in Australia: A History from Flood to Ebb Tide. s.l.:Cambridge University Press.

Campell, D., 1998. Labour Standards, Flexibility, and Economie Performance. In: Advancing Theory in Labour Law and Industrial Relations in a Global Context. s.l.:Royal Netherlands Academy.

Goodwin, M. & Maconachie, G., 2011. Minimum labour standards enforcement in Australia : caught in the crossfire?. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 22(2), pp. 55-80.

Gordon, B., 2014. Designing labor market regulations in developing countries. IZA World of Labor.

Hardy, T., 2011. Enrolling Non-State Actors to Improve Compliance with Minimum Employment Standards. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 22(3).

Hardy, T. & Howe, J., 2013. Too Soft or Too Severe? Enforceable Undertakings and the Regulatory Dilemma Facing the Fair Work Obmudsman. Federal Law Review, 41(1).

Hirsch, B., 2003. What Do Unions Do for Economic Performance?. IZA Discussion Papers .

Landau, I., Cooney, S., Hardy, T. & Howe, J., 2014. Trade Unions and the Enforcement of Minimum Employment Standards in Australia, s.l.: s.n.

Meer, J. & West, J., 2013. Effects of the Minimum Wage on Employment Dynamics. NBER Working Paper No. 19262.

Mortensen, D., 1986. Job search and labor market analysis. In: Handbook of Labor Economics. s.l.:s.n.

Murray, J. & Owens, R., 2009. The Safety Net: Labour Standards in the New Era. In: Fair Work: The New Workplace Laws and the Work Choices Legacy. s.l.:Federation Press.

Naughton, R. & Pittard, M., 2013. The Voices of the Low Paid and Workers Reliant on Minimum Employment Standards. Adelaide Law Review, pp. 119-139.

Oliver, D. & Walpole, K., 2015. Missing links: connections between qualifications and job roles in awards. Labour & Industry: a journal of the social and economic relations of work, pp. 100-117.

Özdurak, C., 2006. Asymmetric Information in Labour Markets. s.l., s.n.

Pantuosco, L. & Seyfried, W., 2008. The Effect Of Public And Private Unions On State Economic Activity: Evaluating The Benefits To Organized Workers, Policymakers, And Companies. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 6(2).

Pittard, M., 2011. Reflections on the Commission’s Legacy. Journal of Industrial Relations, pp. 698-717.

Robbins, S. & Coulter, M., 2012. Management. 11th ed. s.l.:Pearson Education, Inc..

Smith, A., 1776. The Wealth of Nations. s.l.:s.n.

Stewart, A., 2015. Stewart's guide to employment law. s.l.: Federation Press.