How to improve communication - it is important to give and receive feedback effectively

What is feedback?

Feedback is an essential skill in interpersonal communication and the quality of an individual's interpersonal communication can be a determinant in their success or lack of it, in all kinds of relationships.

The term feedback originates from the rocket industry of the late 1940s and early 1950s, when scientists were in the process of perfecting the rockets that would eventually take Neil Armstrong to the moon in 1969. The term was used to describe the circular wireless communication between the telemetry instruments on the ground station with the telemetry instruments on the rocket or launch vehicle. In very simple terms the ground station would be monitoring the progress of the rocket and, based on the information from the on-board sensors would send the rocket new instructions. When these instructions were carried out the sensors on the rocket would report back to the ground station the effect of any changes made. This report was termed "feedback."

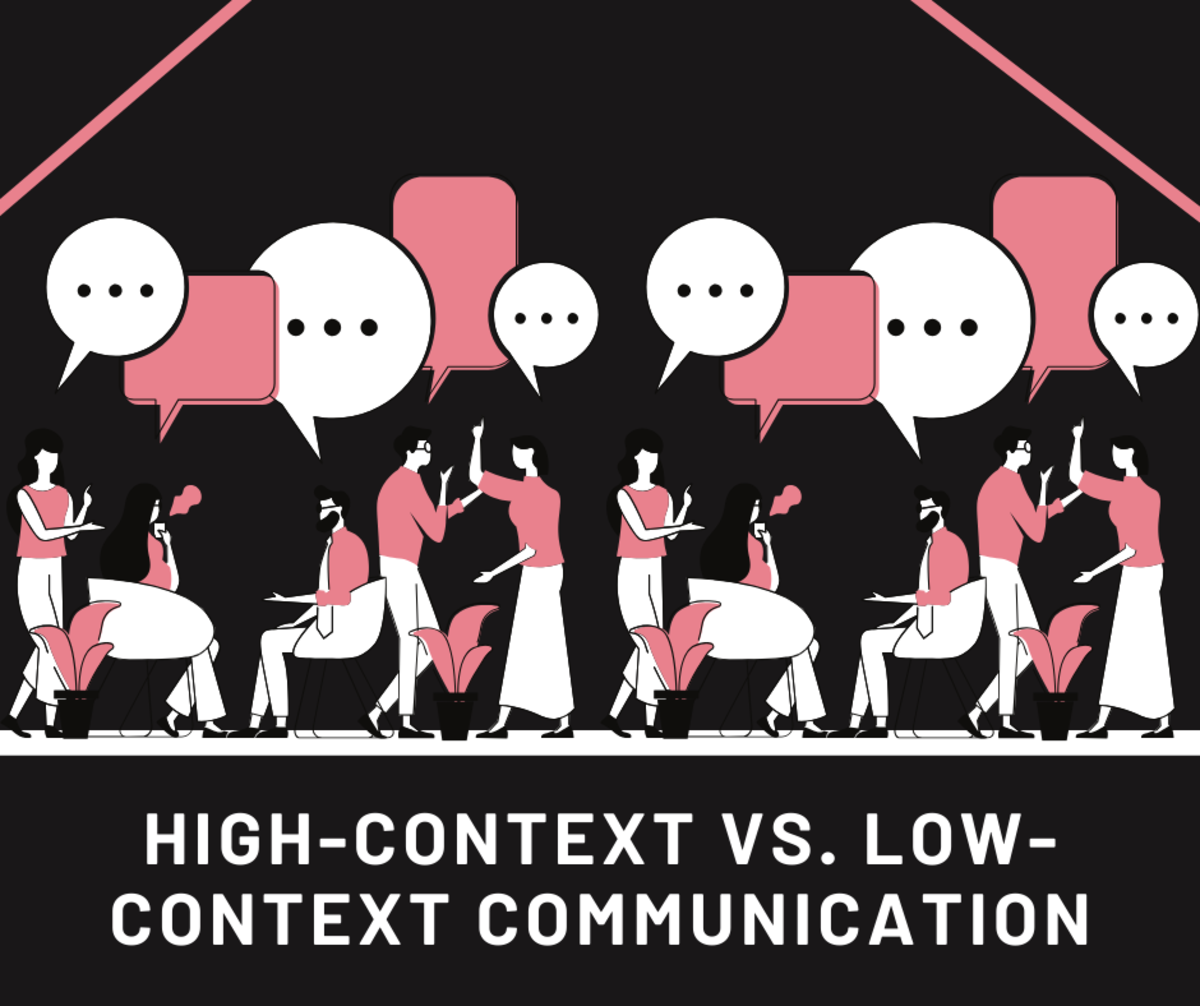

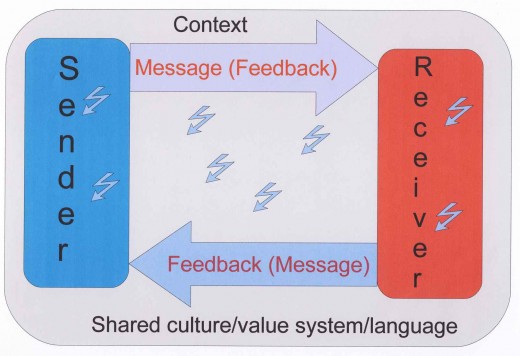

In a similar way, in two-way interpersonal communication the term "feedback" denotes the way a message from a sender impacts on the receiver, as can be seen in the very basic communications model.

The importance of giving effective feedback

The importance of giving effective feedback comes from the concept of self-esteem, which in turn is the value we place on our own self-images. We all carry around within ourselves a picture of who we are - I have a picture of who this person called "Tony" is, and this picture is made up of all the responses I get to what I do and say in my everyday life. I say things to my wife and she responds, I say something to my child and she does something (not always what I might want her to do!), I communicate by email to a colleague and (I hope) get an answer. These responses are all clues to how the other person is experiencing me, and from these clues, these sometimes very subtle messages, I build up a picture of who I, Tony, am.

How people send me these messages has an impact on my self-perception - if they respond to me as if they thought I am an idiot, and it happen often enough, then perhaps I will start to see myself as an idiot, and depending on my opinion of idiots, I might start to think less positively about that self-image I have of myself.

However, I am invested in my self-image, I like it and want to keep it. So if someone responds negatively to my communication, I might perceive that as an attack on me and will try to defend myself - I will tend to build a wall between me and the other person so that their attacks (or what I perceive as their attacks) on me can be warded off. Now I don't know about you but I have never been very successful at communicating through walls. So building that wall of defence around my self-image tends to reduce the effectiveness of my communication with the other person, and this can become a vicious cycle in which I eventually cannot communicate with that person at all, or at best, we are reduced to hurling insults at each other across the barricades.

This happens in social life and in politics also - I'm sure you can think of examples for yourself, either what you have experienced yourself or have seen. Just watch most news broadcasts and you will see what I mean - debate is reduced to shouting slogans across the barricades, sometime literal and sometimes figurative, but always real in their consequences.

When we get into this kind of defensive mode it becomes very difficult to hear each other for the noise. Our communication is thereby seriously compromised.

In many situations this would not perhaps be too serious - if the person we are communicating with is not likely to cross our paths ever again (perhaps that's what you hope for!) or if for some or other reason we do not have much investment in the relationship, then we might not feel inclined to invest anything in making the communication more effective.

The power is in the gap

But usually we are communicating for a reason - we are talking to a boss, an employee who reports to us, a colleague, a child or even a spouse (yes, some people do talk to their spouses!), and then it is in our own best interests to ensure that the communication is understood by both parties. For example, when asking an employee to do a certain task, we would want that employee to understand very clearly what we are asking them to do, and so it is important, indeed very important, that we keep the lines of communication as clear as possible and try to avoid having the employee put up those defenses.

Another, very common example, is in the performance management situation where a manager is giving performance feedback to an employee. This frequently ends disastrously for both, and leads to employees becoming very cynical about the whole performance management process.

The reason for these interviews becoming so fraught is that bosses often become accusatory when giving performance feedback - "you didn't do what I told you to do," and also tend to attack the employee as "lazy" or "stupid" or even, I have heard before, "uncommitted."

The use of these kinds of words is analogous to playing the man and not the ball in soccer. These words tend to impute motives to the other person, motives that, in the way the statements are made, are assumed to be less than honourable.

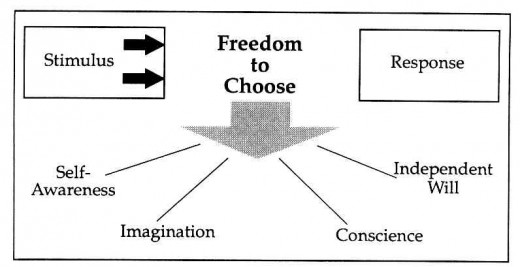

Stephen Covey, in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People , notes that "Between stimulus and response is our greatest power - the freedom to choose." It is that freedom of choice, the opportunity to think through how we should respond to any given situation, that can lift a communication event from disaster to growth.

We can choose how to respond to the message we receive, and in choosing that "how" can make the communication effective.

The "rules" for giving feedback

The first thing to do is to become aware of our prejudices and our habitual responses, because these can cloud our perceptions and give a destructive flavour to our responses. For example, if I am a manager and am about to have a performance discussion with one of my reports, I need to prepare myself by going over everything I know about this person's performance and what I feel about them. I need to be aware of any negative thoughts or perceptions I might have about this person and find ways to overcome them, or at least endeavour to bracket them, to put them aside for the duration of the interview.

In the interview itself I need to give the person feedback on their behaviour, their performance against set targets or standards, without accusing them of "lack of commitment" or any such motives.

In this way the person's defensiveness will be reduced (it can most likely never be totally eliminated - we all have fears when we get into potentially difficult situations) and the communication will be smoother and more effective.

So the first rule for giving effective feedback is to be specific about what (the performance against the agreed standard) and also why the standard is important, why a lack of performance in this case is not acceptable to you, as manager, or to the team. What the effect is of non-performance on the team or on you.

In fact, if you cannot be specific about this, it would be better not to raise the issue at all, because raising it in a vague way doesn't give the other person anything to respond to and they will become very defensive.

The second rule of giving effective feedback is to only give feedback that the other person can act on, something they can do something about. If it is an issue out of their control, giving them feedback on it will be a waste of time and will leave them very puzzled and defensive about it.

The third rule of giving effective feedback is to try always to tell the other person of the effect of their behaviour on you. This is related to the first rule and is applicable especially in no-work-related communication events.

The final rule of giving effective feedback is to avoid, as far as possible, what is called "you language." This is again related to the first rule, and helps to avoid the "playing the man not the ball" situation alluded to above.

There is a sort of formula which can be used to think about when having to give feedback in any situation, and that is to plan the feedback in this sort of form: "When you do/say ... (describe thebehaviour specifically) I feel .... (describe your feelings, not what you think about the situation)."

This will obviously not work in all situations but if used in the planning of your response (which happens in the gap between the stimulus and your response) it can greatly increase the effectiveness of the feedback you give.

The skills of receiving feedback

The skill of receiving feedback is also important for personal effectiveness as we are all frequently at the receiving end - especially from spouses!

To receive feedback effectively is similar in some ways to the effective giving of feedback - the effectiveness comes from the gap between the stimulus and our response.

The first rule is to keep breathing! Seriously, the expression that something we hear is so shocking to us that it "takes our breath away" is not too fanciful. So to concentrate on our breathing when receiving feedback is important. This also helps to keep us "centred" and not falling apart.

Secondly, to remember that whatever is being told to us is the perception of the teller and might have more or less relevance to ourselves. It is not the whole truth" but their "truth."

Thirdly, we can choose to hear the feedback positively. By this I mean that we can hear it as a suggestion for growth, a pointer to how we can become more effective.

Just as it is important when giving feedback to make use of the gap between stimulus and response, so in receiving feedback it is vital to remember the power that is in that gap.

Effective communication leads to personal effectiveness

That power is the power to make our communication more effective, by becoming more aware of it, of how we communicate.

And the more effective your communication, the more likely you are to be personally effective.

Copyright notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2009