- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

1816: The Year with No Summer

As the morning of April 10, 1815 dawned, Napoleon Bonaparte was re-establishing his empire having just escaped exile on Elba. Americans were celebrating the recent victory over Britain in the war of 1812. Unrest in the Balkans threatened to upset the Ottoman Empire. Dutch explorations in Africa were delving into the Congo. And farmers in Indonesia were keeping a wary eye on Mt. Tambora, an active volcano that had been lazily erupting lava for the past five days.

By the end of the day, the noxious gases and ash spewing from the mountain had intensified but it was not until 7 p.m. that the full fury of the volcano was unleashed. Multiple plumes of fire erupted from the mountain, along with ash, pyroclastic bombs and liquid lava, which engulfed the village of Tambora. The level 7 Volcanic Explosivity Index eruption could be heard over 1,000 miles away and radically changed the Earth's climate for the next year. Today, Tambora shows signs that it is beginning to reawaken.

A World Record

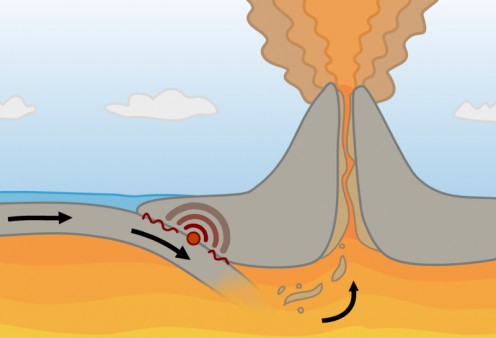

The 1815 eruption of Mt. Tambora is the largest, most powerful volcanic eruption in recorded history. It was four times as powerful as it's more famous cousin, Krakatoa, erupting with the force of 800 megatons. The eruption blew roughly 5,000 feet off the top of the mountain and filled the air with pyroclastic ash and debris that blackened the sky 600 miles in all directions. The force of the explosion also created a tsunami.

Everything on the island was destroyed, including the town of Tambora. Trees were uprooted and became enmeshed with debris and vegetation, washing out to sea in rafts that floated as far away as Calcutta, India. As many as 11,000 people were killed by the initial explosion. The tsunami also resulted in about 4,600 deaths. The real damage was caused by the volcano's after-effects.

After the Heat, the Cold

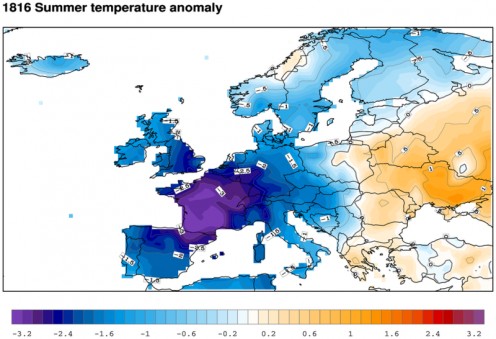

The eruption of Tambora had immediately devastating effects for Indonesia but the entire planet felt the wrath of the explosion. The eruption threw millions of pounds of ash into the upper stratosphere, which was circulated around the globe over the course of the following year. It caused intense optical effects with sunrises and sunsets which were described as "acutely brilliant and colorful" in cities such as London, New York and Beijing. But it also interfered with normal climatic changes, preventing some of the heat and light from the Sun from passing through the atmosphere. The result was abnormally cold weather in 1816.

The areas bordering the north Atlantic were hardest hit by the changes, including Europe, the northeastern United States and eastern Canada. Persistent frost and snowfall into June killed crops and prevented replanting. Lakes and rivers stayed frozen through July and August as far south as Pennsylvania and Maryland. In Ireland and Germany, food prices rose dramatically. Flooding and cold killed rice crops and game animals in China. In the following winter of 1817, New York's Upper Bay froze solid enough for horse-drawn sledges to be driven across it.

The persistent cold and famine after the Mt. Tambora eruption was the worst catastrophe of the 19th century. Some 65,000 people perished and the budding global economy was nearly broken. Food riots broke out in a Europe still recovering from the Napoleonic wars. The full cause for the famine was not understood until much later, once geologic science became full-fledged.

Mt. Tambora Today

Indonesia is the most volcanically active country in the world, with some 155 active centers of volcanism. It's also one of the fastest growing populations in the world, currently at 222 million people. Sumbawa Island, on which Mt. Tambora is located, itself has a population of 1.3 million. Since 2004 active archaeological excavation has uncovered the "Pompeii of the East" in Tambora city, buried by the lava flow of the eruption.

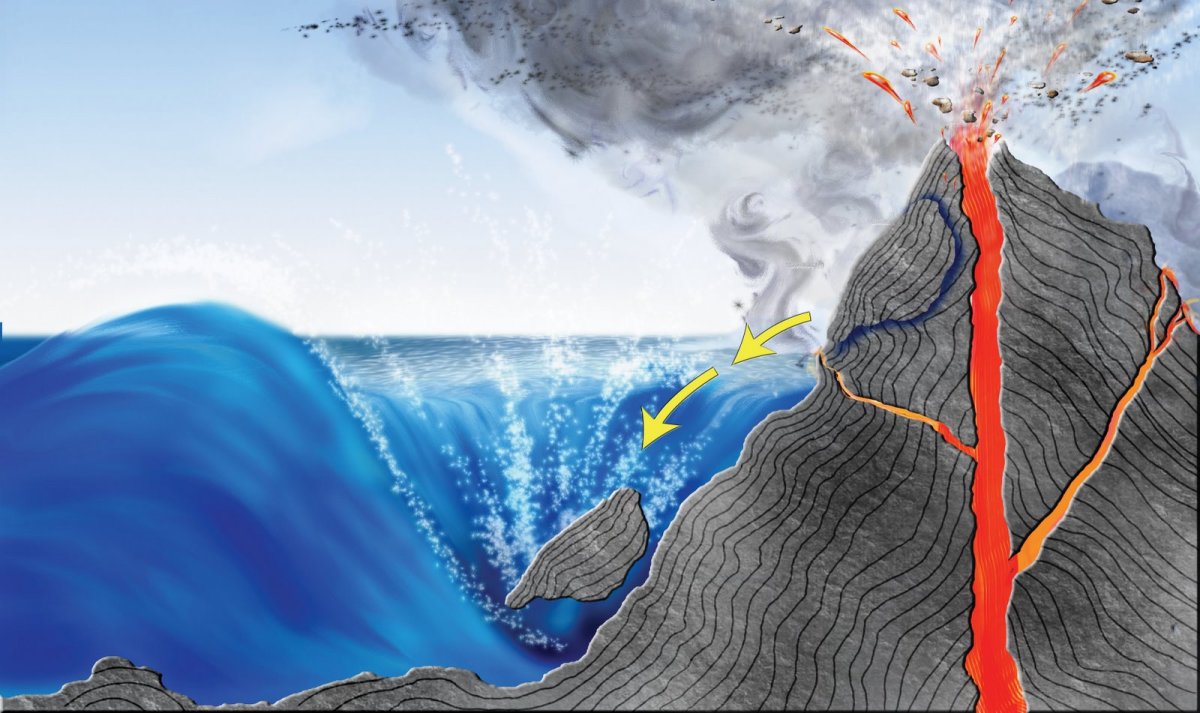

One problem with the exponential population growth, however, is that Mt. Tambora is still an active volcano. Only 200 miles north of the Java Trench, an intensely active subduction zone, Mt. Tambora is fed by the southern plate on which Australia sits being forced under it's own plate, creating abundant magma under the surface of the ocean. The last eruption of Mt. Tambora was in 1967 but it was a smoke, ash and steam eruption; nothing like the level 7 VEI of 1815. In the face of this seeming dormancy, farms and towns have returned to the island. The people who live in it's shadow are well aware of the mountain's power however, and are starting to become alarmed at the rumblings that started this year.

In April, the number of earthquakes in the area increased by 5000% percent, to over 200 a month. These quakes have now subsided. Hundreds of people evacuated and are only just now returning to their homes. Geologists note it takes longer than 200 years to build up the kind of pressure seen in the 1815 eruption, but the fear and respect of the volcano is a deeply instilled cultural tradition for the residents of Sumbawa.

As for the rest of the world, little is known or remembered about this incredible event. Krakatoa, another volcano in the Indonesian chain, erupted with a category 6 VEI in 1888. That eruption destroyed and sank the island but had much fewer casualties and sponsored no world-wide famine. It is more famous though, because the telegraph was in place around the world and news of the volcano traveled everywhere - much like the ash from Mt. Tambora.