3 Reasons for the Writing Crisis and How Elementary Teachers Can Help

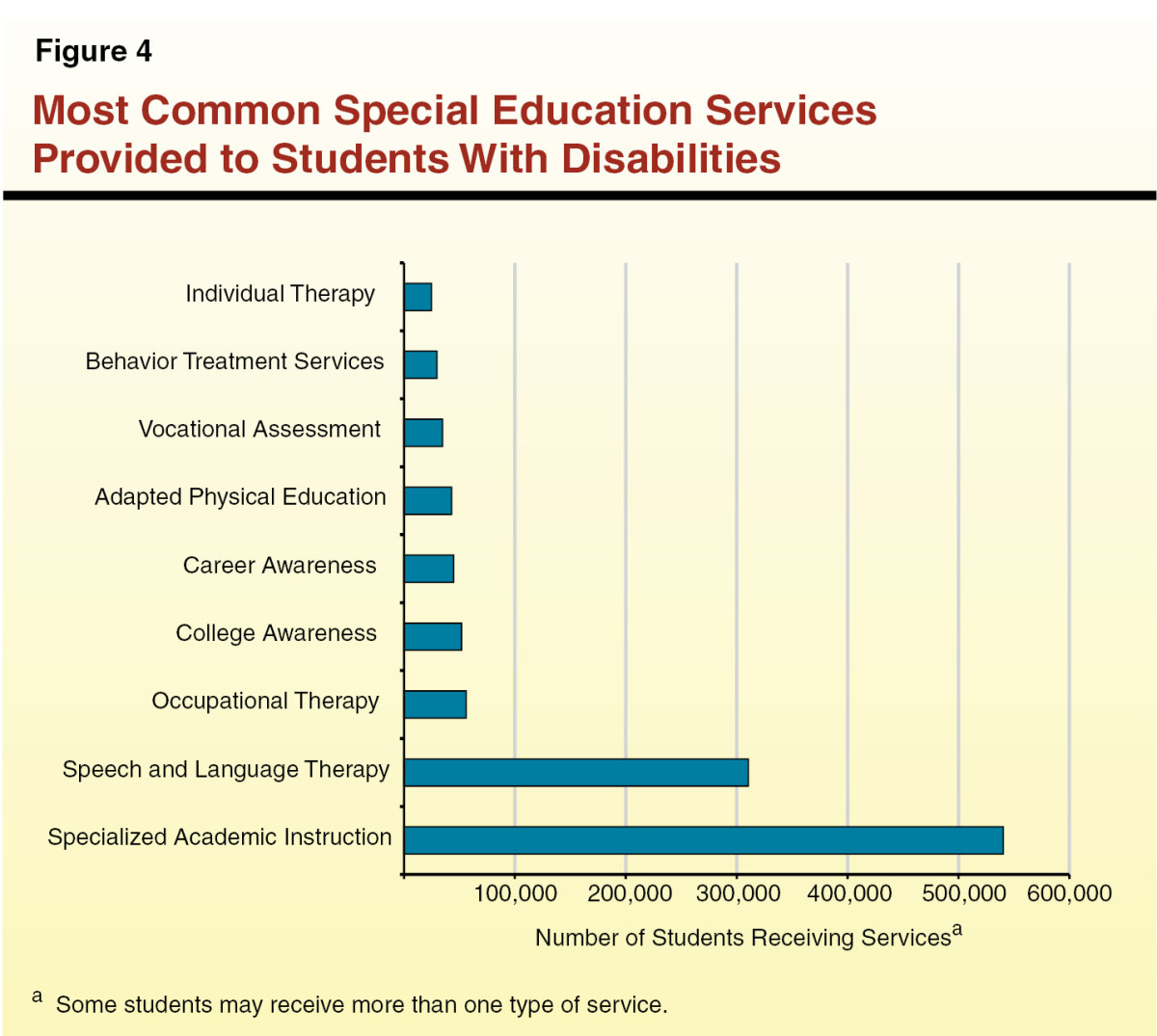

According to the most recent data reported by the National Center for Educational Statistics, only approximately one quarter (24%) of U.S. students are writing at a proficient level. Dr. Steve Graham, an education professor at Arizona State University who specializes in writing instruction, says this is problematic because students who have poor writing skills are less likely to do some of life's most important things, such as graduate from high school, attend college, or attain a white collar salary. At an increasing rate, professors and bosses are lamenting the dearth of writing skills of college students and employees. This phenomenon is a writing crisis. Writing instruction begins in elementary school, so it would make sense to examine the three most harmful and three best instructional practices for teaching elementary school students to write well.

Here are the three least effective practices for teaching writing to elementary students and what teachers should do in their place to begin solving the writing crisis.

Using worksheets to teach grammar

Far too many people look back and remember their school days filled with fill-in-the-blank worksheets to practice punctuation, capitalization, subject-verb agreement, and other grammatical skills. The problem with this is that virtually all academic research conducted on how best to teach grammar indicates that teaching it outside the context of authentic texts is not optimal. Not only that, but this approach is tedious and unmotivating for students. Instead of using worksheets, most researchers agree that the best way to teach students grammar is within the context of real reading and writing tasks rather than in isolation in workbooks. Dr. Lucy Calkins from the Teachers College at Columbia University and founder of the Reading & Writing Project advocates for the use of ONE mini-lesson at the beginning of a particular block of writing instruction. This mini-lesson should address only one single grammatical, strategic, or stylistic skill, followed by plenty of practice applying that one skill while engaging in authentic writing.

Too many teachers have contracted the red pen syndrome

Imagine a young six-year-old first grader has finished writing her first story. She was meticulous as she drew each unicorn, she incorporated dialogue and even remembered to put a period at the end of each sentence. Later in the day, the teacher hands back her story. When the girl looks at her story, she notices that the teacher has circled the first letter of each sentence with ink. She has also crossed out what was supposed to be the words "castle" and "princess" and written them correctly under the misspelled words. At the top of the paper, the teacher has written (still in red ink), "9/10: did not capitalize". What kind of messages are this teachers' practices sending to this little girl? All she knows from this exchange is that she made some mistakes but still did pretty well. Multiply this transaction by the number of times teachers have handed stories back to their students per year, and the inevitable result is that students begin to believe writing is about being correct in their mechanics. This will likely distract from what the student has to say, and will almost surely ruin the joys that writing can be.

Feedback is one of the most powerful influences on learning and achievement, but this

impact can be either positive or negative.

— John Hattie & Helen TimperleyDr. Peter Elbow, Professor of English Emeritus at the University of Massachusettes at Amherst, argues that when teachers mark each error in a student's writing, the unintended and dire consequence is that students will not want to write at all, due to the fear of being wrong. He advocates instead for the use of freewriting in classes so students can focus on ideas. Obviously, this does not mean students should not receive instruction in grammar, but as previously mentioned, teachers should give feedback on the specific skill the class was working on for their mini-lesson that particular day. Keep in mind that not all feedback should focus on what students need to fix or what they did wrong because it is equally important to give praise for any useful strategies or skills students employ in their writing.

Not giving students enough time to write each day

The United States Department of Education recommends that elementary students write for a minimum of 30-60 minutes during each school day. University of Tennessee Professor Dr. Richard Allington claims that most teachers come nowhere near meeting this goal. He argues that this is because too many teachers engage students in activities that have no effect on achievement. These activities include worksheets, computer programs, and whole group lecturing. Teachers should curtail most, if not all of these activities, in favor of giving students ample time to write.

Calkins recommends that each writing block be about an hour long, with no more than ten minutes devoted to teaching a mini-lesson and five minutes for students to share their writing with the class at the end of the. The remaining time should be devoted to allowing students to practice independent writing.

Many times motivation can play a role in how long students are able or willing to write. Some students will sit and fiddle with their pencils, distract others, ask to go to the restroom, or do just about anything to avoid writing. How can teachers expect these students to write for a full thirty minutes if they resist touching the pencil to the paper, and what can they do to increase motivation for reluctant writers? One of the practices Allington and other experts recommend for increasing writing motivation is allowing for self-selected writing, which means students make choices about their topics, within reason.

The writing crisis will not be solved overnight, but it will persist until more teachers abandon these three unhelpful instructional practices by focusing on authentic writing experiences rather than worksheets, positive and targeted constructive feedback rather than correcting every little error and allowing much more time for writing in the classroom. If teachers do not adjust their writing instruction, students will suffer the consequences throughout their lives.