A Basic Guide To Animal Migration

Travelling The World

Formation Flying

Hazards Of Travel

During their annual migration, Burchell's zebras must risk crossing the crocodile infested waters of the Mara River in Kenya's Masai Mara game reserve.

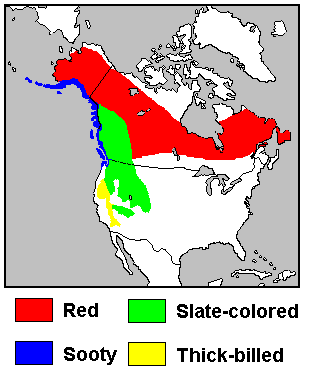

Leapfrog Migrations

How Ocean Animals Navigate

Illegal Immigrant

Suez Canal

Introduction

In basic terms migration is the periodic movement of animals to and from different areas, usually along well-defined routes. In long lived species, individuals make repeated annual migrations throughout their lives once they are sexually mature. In short lived species, such as the monarch butterfly, which produce several generations within a season, the migration therefore, is undertaken by a succession of different individuals as the butterflies breed along the route.

But what compels an animal to migrate in the first place? Many migrate to find the best location in which to lay eggs or rear young. This is often related to the need to avoid the lack of food in one area and exploit an abundance of food elsewhere. Such movements are usually in response to predictable changes in the environment, for example the different seasons in temperate latitudes, where weather conditions vary from harsh to favourable, and the wet and dry seasons in the tropics.

So, we know why animals migrate, but how do they know when the time to migrate has arrived? Well, all migratory animals rely on a series of instinctive triggers, which can include lengthening days as spring arrives, an increase in reproductive hormones and fat deposits, and growing restlessness. Many animals have an innate, near annual rhythm that tells them when to migrate. Once they are in good condition, favourable weather may be the final trigger to move. Physiological changes are often necessary before setting off. For example a birds’ heart, flight and skeletal muscles enlarge, while other organs may diminish in size. While migratory fish that move between fresh and salt water display changes in their levels of salt tolerance, whereas amphibians that move between terrestrial and aquatic habitats alter the permeability of their skin.

But how do migrating animals always seem to find their way? Well, they use various cues to aid them in navigation. Compass cues indicate direction and might include the sun, stars, or the Earth’s magnetic field. Visual cues or landmarks, such as coastlines and mountain ranges, are used by animals to pilot their way towards their goal. Distinctive odours are also used to home in on breeding or roosting sites. True navigation relies on a mental map to determine their position relative to their destination. In some species, young birds migrating for the first time travel with the adults in flocks, but in many the adults leave first and the young follow on later. They are born with the information for the distance and direction of their journey.

In the Animal Kingdom there are two kinds of migrants. A full migrant is basically when all of the individuals in a species migrate. A partial migrant on the other hand is when certain individuals within a species elect to remain resident in parts of their range. Whether or not an animal migrates can depend on local climate. For example, in Finland most European robins migrate south to escape the harsh winter, whereas in the British Isles, where winters are milder, most robins remain all year round. Migration can also depend on the stage an animal has reached in its life cycle. An immature American or European eel, for example, has no need to migrate to breeding grounds; it will make the journey from inland waterways to the Sargasso Sea when it is ready to reproduce. Migration may also depend on an animal’s circumstances. Older, more experienced common blackbirds in possession of a territory remain resident while younger, less experienced birds migrate.

Migrations as you can imagine are often long and hazardous journeys. Some birds choose to travel over land even though it is a longer journey, while others go over the sea by the shortest route, where there are fewer predators and where, also they can benefit from tailwinds. But birds migrating over open sea risk winds blowing them off course (resulting in birds stopping in places they are not normally seen) or storms forcing them to land on water. There may be also an increased risk of predation at journey’s end: in autumn, the Eleonora’s falcon preys on exhausted songbirds that have flown over the Mediterranean to North Africa. Migrating over land can have its hazards too, such as crossing inhospitable places like deserts.

Animal migration though does have an added dimension, especially when you consider the extraordinary growth of the human species over the last few thousand years. In that comparatively short time, humans have moved around the world for various purposes, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Goats were introduced to many oceanic islands to provide food for passing ships. In many cases, they have since caused significant environmental damage by stripping the land bare of vegetation. People have also taken animals, such as cats, to new places as pets, where they then kill local fauna. Additionally many species have been introduced in an effort to control others. For example, cane toads were imported to Australia to eat pests of sugar cane, but instead they eat almost anything else.

One interesting case study of the human impact on animal migration was the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which connected the northern end of the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. For a long time the Bitter Lakes, which was part of the canal was so salty that few animals could survive in it. However, over time the salinity has gradually decreased, allowing Red Sea species to travel northwards into the eastern Mediterranean. This movement is known as Lessepsian migration after the engineer of the Suez Canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps. Thus far, at least 300 species are known to have made this human assisted migration.

Below, I shall briefly profile some of the most famous animal migrations known on the planet today:

Record Migrations

Record

| Animal

| Distance/Number

|

|---|---|---|

Longest Round Trip

| Sooty shearwater

| 40,400 miles

|

Longest non-stop flight

| Bar-tailed Godwit

| 7,200 miles

|

Highest journey

| Bar-headed goose

| 33,380 feet

|

Longest aquatic journey

| Grey whale

| 12,400 miles

|

Largest land migration

| Blue wildebeest

| 1.3 million

|

Largest air migration

| Desert locust

| 69 billion

|

A Flutter Of Butterflies

Monarchs In Mexico

Mass Migration: Monarch Butterfly

One of the most conspicuous of all insect migrations is that of monarch butterflies in North America. In autumn, they move south to avoid the cold temperatures of more northerly parts of the continent. They overwinter in milder climates in a state of reproductive diapause, meaning they do not breed during this time. In spring, these striking butterflies move north in search of their food plant, milkweed (plants of the genus Asclepias, which produce milky sap). As they move, females lay eggs and die, and the new generations continue the journey. By the time they have reached the most northerly parts of their range, the butterflies will be second, third, or even fourth generation descendants of those that left in the south.

The migration of the Monarch butterfly appears to be triggered by changes in day length and temperature. Also, it seems that there must be a genetic component to the species that allows flight routes to be inherited by offspring, as no individual butterfly ever makes the journey twice. The overwintering populations of monarch butterflies in Mexico are threatened by destruction of their forest refuges for timber; intact forest is vital to maintain the microclimate needed for the butterflies’ survival. Gaps in the forest cover can leave the butterflies susceptible to cold and rain. In recent years several sanctuaries have been established for the protection of monarch butterflies.

The Monarch Butterfly Migration

The Salmon Run

Heading Upstream: Chum Salmon

Unlike many typical freshwater fish, salmon are anadromous, meaning that they live mostly in the sea but return to fresh water to breed. Chum are one of five species of salmon that frequent the North Pacific Ocean and the rivers that border it in countries including Canada, Japan, Korea and the USA. After spending between one and three years at sea, chum salmon travel inland as far as 2000 miles up the Yukon River through Alaska into Canada. The annual ‘salmon run’ occurs during autumn, with spawning taking place between November and January. Around two weeks later, the adults die, contributing valuable nutrients to the ecosystem. Their eggs remain protected in the gravel riverbed over winter and hatch in early spring. The fry stay in the river for a year or more before travelling downstream to the sea between March and July.

As with most animal migrations today, the impact of our own species must be considered. Unfortunately as most of us are aware, salmon is a very popular food fish, which has consequently prompted a boom in commercial salmon farming. However, the industry is threatening wild salmon populations by exposing them to parasites. Sea lice are crustaceans that occur naturally on the salmon’s skin, but the rearing of thousands of adult fish in close proximity in pens cause’s parasite numbers to rise far beyond normal levels found in the wild, lowering the fitness of the fish. Young wild salmon migrating downstream from their spawning grounds pass the salmon farms on their way to the ocean and become infested with parasites as they go.

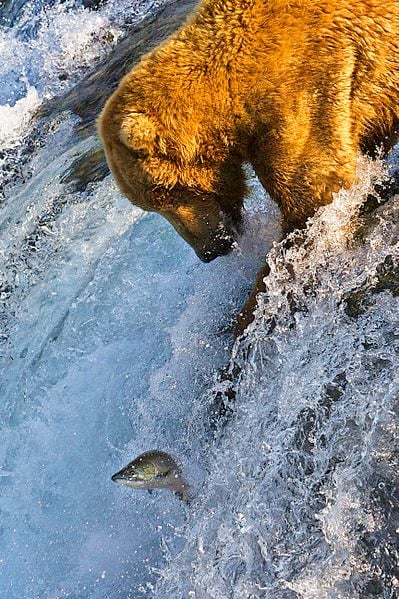

Grizzly Bears Vs. Salmon

Landfall

Mission Accomplished

Long Distance Swim: Leatherback Turtle

This giant of the ocean makes lengthy annual migrations. Using ocean currents to help it on its way, the leatherback turtle feeds in the rich, temperate waters of the northern and southern Atlantic and Pacific oceans in spring and summer, but it returns to more tropical climates to find beaches on which to lay its eggs. Although only females venture onto land, males also migrate, coming close inshore to mate with the females. Satellite tagging has revealed extensive migrations: one record setting leatherback was tracked swimming 12,774 miles from a beach in Indonesia across the Pacific to the west coast of the USA and part of the way back again. Leatherbacks are prone to eating plastic refuse, mistaking it for jellyfish, and can choke to death as a result. They are also sometimes caught in fishing nets.

As previously mentioned we know exactly how far leatherbacks can swim through the method of satellite tracking. But how did human scientists accomplish this in the first place? Well, they fitted female turtles with tags that are mounted on harnesses that are designed to disintegrate gradually and fall off the turtle. They are usually fixed to the females once they have finished nesting and to males that are accidentally caught at sea by fishermen. For up two years, a tag can relay information about a turtle’s whereabouts via satellite to a computer. In addition to location information, the tag transmits data such as the depth and duration, which give clues about behaviour such as foraging.

David Attenborough And Leatherback Turtles

Communal Feeding Grounds

An Epic Journey

Longest Non-Stop Flight: Bar-Tailed Godwit

This large wading bird is a long distance globetrotter, capable of flying non-stop from breeding ranges in the Arctic regions of Europe, Asia and western Alaska across the Equator to feeding grounds in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. During the northern hemisphere summer, bar-tailed godwits are resident on the coastal tundra of the far north, where they lay between two and four eggs in cup shaped nests in the grass. After rearing their young, the birds fly to ‘refuelling stations,’ such as estuaries, to feed and bulk up their bodies before flying south to the southern hemisphere. Then, as the southern hemisphere winter approaches, the birds moult into their russet-coloured breeding plumage and put on weight in advance of their northward migration. Some bar-tailed godwits overwinter in Europe, so are closer to their breeding grounds and require less energy to get there. Although their feeding rate is the same as birds that migrate from Africa, they spend less time feeding before they begin their journey.

In 2007, biologists fitted satellite transmitters to 13 bar-tailed godwits on their feeding grounds in New Zealand. They were about to witness the longest non-stop flight ever made by a bird. A female nicknamed E7 left the mouth of the Plako River on the 17th March and flew 6340 miles non-stop to Yalu Jiang, China, arriving on the 24th March. She spent five weeks there before leaving on the 1st May and travelling to Alaska, stopping occasionally en route. E7 arrived at her breeding grounds at Manokinak on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta on the 15th May, where she stayed until the 17th July, before moving to another site in the delta. On the 29th August, she departed and smashed her own record by flying non-stop to New Zealand, a distance of 7200 miles, in just over 8 days.

Running On Snow

New Life

Endurance Test: Caribou

Caribou undertake one of the most arduous annual migrations of any terrestrial mammal. Herds may numbers and complete a 3000 mile round trip, visiting spring calving areas and summer and winter foraging grounds. They are forced to move on by the seasonal availability of the tundra plants on which they feed. In summer, the herds take refuge from flies and mosquitoes in windy coastal areas; in winter, they move into subarctic boreal forests, where snow cover is less than on the open tundra. Caribou herds have been recorded running as fast as 50 mph while migrating. Groups are largest during the spring migration and smaller during autumn, when mating occurs. Caribou are also called reindeer, particularly in Europe and Asia, where many are partially domesticated and are tamer than wild animals. Reindeer from herds in Eurasia have been introduced to North America, where they may mix with the native caribou.

Native peoples of the Arctic and subarctic have a close association with reindeer, stretching back thousands of years, relying on them for food, skins and transport. They live a nomadic life, moving with the semi-domesticated herds as they make their way between the coast and inland areas. Reindeer are rarely bred in captivity, but they have been tamed for milk production and to pull sleighs. Reindeer are a particularly aspect of the Nenet culture in Siberia, where they are used to transport people and belongings across the snow covered pastures. Reindeer herding is also an important part of the Sami culture in northern Scandinavia (Lapland). Native peoples in North America and Greenland have a long history of hunting wild caribou for their meat and hides.