- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Paleontology»

- Prehistoric Life

A Muddy, Bloody Trail

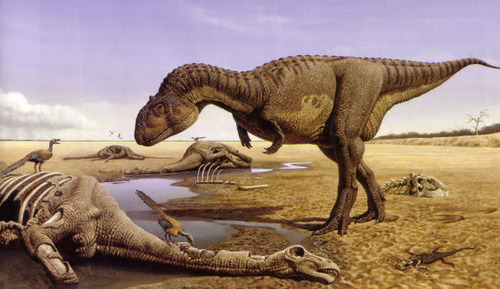

Of all the topics discussed in the study of meat-eating dinosaurs, the T. rex predator-or-scavenger question has arguably gotten the most media attention over the past twenty-some years. With all the focus on this iconic dinosaur, though, the same question is rarely asked of other large, carnivorous theropods. Like T. rex, we often see them depicted chasing startled ornithopods or grappling with towering sauropods. Yet how do we know that Allosaurus risked life and limb for a taste of Stegosaurus meat, or that giant carcharodontosaurs dared to go after titanosaurs many times their size?

The safe answer would be that the whole hunter-scavenger question is a false dichotomy: Like all living flesh-eating vertebrates--including vultures and hyenas--T. rex and its brethren would have gladly fed on unspoiled carcasses whenever they came upon them; but when fresh carrion wasn't available, they did hunt large, often dangerous prey. Is there support in the fossil record for this reasonable conjecture, though? The bones of large theropods (with a few notable exceptions) are generally uncommon in dinosaur bonebeds and clues about their feeding behavior are rarer still.

Fortunately, we are lucky enough to have found clues of this kind in four large, clearly carnivorous theropods that are not T. rex. Each of these monsters hails from a different family and bonebed, and most of them shared their habitat with other potential predators.

Allosaurus

Time: c. 156-150 million years ago

Location: Western and Southwestern United States, as well as Portugal

Profile: Often dubbed the "lion of the Jurassic", like the lion it may have been a keystone predator--an unfussy hunter so ecologically vital that its ecosystem would collapse without it. Not every feature of its body points to it being a perfect killing machine, though. Its lightweight jaws left something to be desired, with a bite force on par with modern leopards, despite belonging to an animal ten times their size. And depending on which source you consult, it was either fast enough to catch whatever it wanted or had to rely on ambush tactics to compensate for its bulk. Still, its arms were long and tipped with six-inch, hook-like claws that would have been formidable weapons.

Rivals for Prey: Allosaurus shared its habitat with the smaller horned theropod Ceratosaurus and the similarly-sized megalosaur Torvosaurus. However, both of these animals are rare in Jurassic bonebeds (in contrast to Allosaurus, which is the large theropod known from the most specimens).

Evidence: Deep gashes and bite marks matching those of Allosaurus claws and teeth have been found in the skeletons of many of the large local herbivores. In most cases the intent behind these marks is ambiguous, but one Stegosaurus plate have a U-shaped chunk taken out of it matching the muzzle of Allosaurus. More striking, though, was a punctured Allosaurus tail vertebrae with a hole in it that was the right size and in the right position to have been caused by a Stegosaurus tail spike. Both of these events were recreated in 2011 BBC documentary Planet Dinosaur (above).

Baryonyx

Time: c. 130-125 million years ago

Location: Western Europe

Profile: Baryonyx is the poster-child for fish-eating dinosaurs, with long, crocodile-like jaws for snatching fish and large, hooked claws for tearing them open. It is also the spinosaur known from the best fossils.

Rivals for Prey: On the modern Isle of Wight, Baryonyx lived alongside Neovenator and Eotyrannus, while in Spain, it lived at the same time as the humpbacked carcharodontosaur Concavenator.

Evidence: The type (original) specimen of Baryonyx was found with the bones and scales of the ancient fish Lepidotes in its gut. The same specimen, however, had another partially digested meal in it as well: The bones of a juvenile Iguanodon. Though it grew about the same size as adult Iguanodon (roughly thirty-three feet long and a few tons) and was larger than any of the other theropods it shared its habitat with, there's no way of knowing from these bones alone whether the Baryonyx killed this local herbivore or just lucked upon its remains.

Was Baryonyx a hunter or scavenger of dinosaurs?

Acrocanthosaurus

Time: c. 120-112 million years ago

Location: Southwestern and possibly Eastern United States

Profile: Acrocanthosaurus is the second-largest meat-eating dinosaur from North America, as well the northern-most carcharodontosaur known to science. While its arms were proportionately shorter than those of its Jurassic predecessor, they were heavily muscled and the animal on the whole had a much more robust build. Like Allosaurus, however, the jaws of Acrocanthosaurus were more suited for cutting than crushing, and the movements of its arms were much more restricted than one would expect.

Rivals for Prey: Fossils of Deinonychus--the dromaeosaur that the Velociraptors in Jurassic Park are based on--have been found nearby those of Acrocanthosaurus. However, the latter had a huge size advantage over the former, and would have been more than capable of stealing kills from Deinonychus, or even making a meal out of it.

Evidence: This giant is not known from as many fossils as Allosaurus or even T. rex. Yet sets of large theropod trackways from about 115 million years ago that have been unearthed near Glen Rose, Texas, are a perfect match for Acrocanthosaurus feet. What makes these tracks special, however, is that they closely follow those of a large sauropod, most likely a contemporary brachiosaur like Paluxysaurus. Whether the Acrocanthosaurus was merely stalking the towering herbivore from far behind or actually managed to get close enough to take bite out of it, this monster was pursuing live meat.

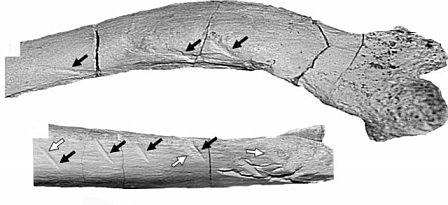

Majungasaurus

Time: c. 70-65.5 million years ago

Location: Madagascar

Rivals for Prey: None on dry land. Though it lived alongside Mahajangasuchus, a crocodylomorph resembling modern alligators, Majungasaurus was over twice its size.

Profile: Of the abelisaurs, Majungasaurus is the one known from the best fossils. Like other members of the family, it had a short, high skull, shorter legs than most theropods, and laughably short arms. While these features might not add up to a promising-looking hunter, Majungasaurus is the largest carnivore known from Late Cretaceous Madagascar and would not have needed much speed to catch up with the island's largest herbivore, the saltasaur Rapetosaurus. It also had a small horn between its eyes, though this was more likely a display ornament than a weapon.

Evidence: Though bite marks matching Majungasaurus jaws have been found on the bones of Rapetosaurus, it is far better known among dinosaur enthusiasts as the first confirmed cannibal among dinosaurs, based on similar bite marks on their own bones. It's not clear whether the animal hunted one of its own kind or just fed off of its carcass: The gauge marks made by Majungasaurus teeth could indicate either the tearing flesh from bone or a struggling victim.

SOURCES

Barrett, Paul. National Geographic Dinosaurs; National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., 2001

Highfield, Roger. "How Allosaurus Used Its Head When It Came to Hunting." The Telegraph, 22 Feb 2001

Holtz, Thomas R. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-To-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages; Random House Inc., New York, NY, 2007

www.prehistoric-wildlife.com

Switek, Brian. "Watch Out For That Thagomizer!" Smithsonian Magazine, Mar 30 2011

Switek, Brian. "Fearsome Dinosaur Had Ridiculously Short Arms." Smithsonian Magazine, 24 Jan 2012

Switek, Brian. "In the Steps of a Hungry Acrocanthosaurus." Smithsonian Magazine, 28 Jun 2012