A Teacher's Response to Behavior and Information Processing in the Adolescent Brain

The human brain hasn’t fully developed until a person is in his twenties. This development includes some major benchmarks and subsequent instabilities during the adolescent years. Naturally, these changes affect every aspect of a teenager’s life, including his education. It is imperative that secondary educators take into consideration the growth spurts and changes in their students’ brains that attributes to a variety of cognitive, emotional, and social processing abilities, and teach accordingly.

Prefrontal Cortex

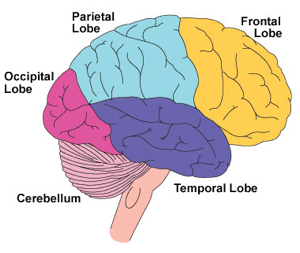

The brain is the most complex part of the human body. Each part has a significant responsibility and role, yet in adolescence, several parts of the brain are still under development. The prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for “higher cognitive abilities such as alertness, attention, planning, working memory, and regulating appropriate social behavior” and controlling impulses is still under development during these years (Hall 25). Therefore, teenagers tend to lack judgment as well as executive skills. Executive skills are those skills that help control behavior, organization, and scrutinize thinking, emotion, and actions in order to be more resourceful and socially appropriate.

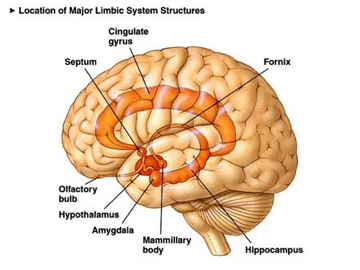

The prefrontal cortex is the largest part of the brain yet is the slowest to develop. Instead of using the prefrontal cortex, teenagers use the amygdala, which is responsible for emotions like fear, rage, and other “gut reactions”, leading to an increase in emotional instability (Caskey 37). A study by Deborah Yurgelun-Todd conducted at Boston’s Mclean Hospital showed a group of 11-17 year old students pictures of people with looks of fear on their faces. By using brain scan technology she discovered that students under the age of 14 used their amygdala more than the frontal regions and misread the expression as “sadness, anger, or confusion” instead of fear (Spano 38).

This translates into information processing and school success in that students may have difficulty interpreting information and making proper judgments about material.

Limbic Cortex

Along with the prefrontal cortex, the limbic cortex, which regulates emotion, attention, and memory is also under development. When a teenager forgets to complete homework, it might not be from defiant carelessness, but merely from the fact that his brain hasn’t fully developed and he is incapable of remembering. In addition, teenage years can beget awkwardness, as the parietal lobes, responsible for visual, auditory and spatial ability, go through a growth spurt in puberty and are “immature until age 16” (Spano 38).

Teenage years can also be awkward because of all the emotional turmoil. It is possible that the spikes in emotional instability aren’t solely from raging hormones, but from an uncompleted brain. The limbic cortex, frontal lobes, and temporal lobes, all used to regulate emotion, are not finished developing yet, so emotions are unstable. Teenage drama isn’t merely a cultural issue, but a developmental one. Unfortunately, the uncomfortable changes in the teenage years surely affect a students’ schooling and his ability to process information.

Connecting Neurons

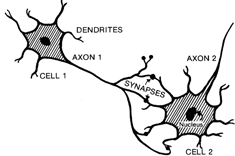

The brain is a complex system of neurons communicating with each other through electrochemical signals. There are three parts to a neuron: the dendrites, the cell body, and the axon. The dendrite acts as the receiver for the incoming signals, which then are sent to the cell body. The cell body processes the information and responds to it before sending out an “action potential” through the axon. This signal goes to synaptic terminals “where the information is converted into chemical signals” and sent on to other neurons.

Around the axon is a fatty cell called myelin that insulates and protects. During adolescence, myelin production increases in order to aid the communication between neurons and make it more efficient. This extra boost of myelin in neurons connecting the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system demonstrates that these areas are still under much development and are working on ways to make connections more efficient (Hall 26).

Pruning

Coupled with the increase of myelin in making efficient connections, the adolescent brain also undergoes a process called pruning. In the first time since infanthood, a teenager’s brain overproduces gray matter, which plays a pivotal role in the central nervous system and carries many cell bodies. The pruning process is straightforward in that those connections that aren’t used essentially “wither away” (Spano 37). The functions and thought processes that your brain doesn’t use in adolescent years will disappear. On the contrary, those “that are used repeatedly become strengthened and stabilized into functional circuits” (Caskey, 37).

Therefore, it is essential that good habits are cultivated amongst adolescence lest the connections responsible for acceptable behavior and higher order functioning become nonexistent. Teens using alcohol and drugs can suffer long term effects, as the pruning process is effected by their abuse. Essentially, teenagers may be capable of controlling how their brains function for the rest of their lives if they are cognizant of the development going on inside their skulls.

The Teacher's Responsibility

It is our responsibility as teachers to cater to our students’ needs in order for them to learn to their highest potential. Therefore, we must take into consideration the emotional, social, and cognitive development occurring for secondary students when planning lessons. First, it is important to educate ourselves about teenage brain development and keep up to date with the latest research.

Secondly, sharing our findings and teaching students about their brain, specifically the pruning process and what portions are still under development, will bring awareness to the importance of their choices. Not many students are aware that the choices they make as a teenager actually molds their brains for the rest of their lives. In a lesson regarding brain development, teachers can discourage harmful choices while promoting healthy ones. Students will also need opportunities to rehearse and practice those good decisions.

Teachers can even do little things in the classroom to help students process information to the best of their cognitive ability and encourage healthy brain development. Clusters of teachers should adopt curriculums, or present material that allow for connections across subject areas. This way, the neural connections made in the brain will not be isolated by subject but will combine together to create one big network with more easily accessible information across subjects.

It is also important for teachers to nurture curiosity in the classroom. Perhaps inquiry learning should be adopted, as well as other ways that students can discover meaning for themselves. Because working memory and organizational skills may be lacking, teachers should maintain firm due dates, keep a record of daily class activities (which is especially useful for students coming back from an absence), provide a unit organizer so students can keep track of what assignments they have done, and use the same format for assignments. Any extra boost of organization implemented by the teacher will greatly increase the success of a secondary student going through the chaos of brain development.

Modifying Habits and Behavior

Fortunately, habits and behaviors can be modified with the right amount and type of support. Students showing weak executive skills, often leading to defiance and inconsistency or refusal to do work so not to look incompetent, need extra support from all adults in their lives. Richard Guare, Ph.D. and Peg Dawson Ed.D. of the Center for Learning and Attention Disorders in Portsmouth, NH suggest that direct instruction and environmental supports in school should be implemented. These can be homework clubs or extra time with a “coach” who will work with the student to make plans to help organize assignments.

At home, they suggest that parents and child make a contract, mediated by a therapist, to set clear expectations of behavior at the home, including completion of chores and an incentive program. Controversially, they also recommended that students consult with a physician about medication to suppress impulsivity of certain students to “impact task initiation, [sustain] attention and working memory” (Guare 7). However, this should be a last resort if natural methods are not effective.

It is obvious that as certain areas like the prefrontal cortex, the limbic system, and temporal lobes develop, the life of a teenager seems to go in various directions. As teachers, we can make our students aware of the pruning process happening and encourage them to make good choices while we stand in the gap with all the support we can give.

In Summary

The human brain isn’t fully developed until a person reaches his 20s. Adolescents undergo a pruning process where unused connections wither away and used ones are enforced and strengthened. Along with this process, several areas of the brain have not reached their maturity. They include:

- Prefrontal cortex: higher cognitive abilities like alertness, attention, planning, working memory, and regulating appropriate social behavior, as well as self control and judgment

- Limbic cortex: emotion, attention, and memory

- Temporal lobes: language and emotional maturity

- Parietal lobes: visual, spatial, auditory and tactile abilities

As teachers, there are several things we can do to help our students learn to their highest potential considering their brains haven’t fully developed:

- Educate yourself on adolescent brain development

- Share information with your students about what their brains are going through and how their choices actually affect the connections made in their brain for the rest of their lives.

- Discourage harmful choices and promote healthy ones, especially involving drug and alcohol use.

- Give opportunities to rehearse and practice good decisions.

- Nurture curiosity in the classroom.

- Adopt cross discipline curriculums and material that will strengthen connections in your students’ brains.

- Increase support: Direct instruction, Environmental support, Coaching, Home support, Therapy

- Modify behavior by helping students use skills, perhaps with an incentive system.

- Maintain firm due dates.

- Keep a record of daily class activities.

- Provide unit organizers.

- Use the same format for all assignments.

Works Cited and Additional Readings

Caskey, Micki M. and Barbara Ruben. “Research for Awakening Adolescent Learning.” The Education Digest. (Dec 2003): 36-38. Academic Search Premier. Web. 15 May 2010.

Guare, Richard Ph.D., and Peg Dawson Ed.D. “Executive Skills in Children and Teens – Parents, Teachers and Clinicians Can Help.” The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter. 20.8 (Aug 2004): 5-7. Academic Search Premier. Web. 15 May 2010.

Hall, Megan and Georgia Brier. “From Frustrating Forgetfulness to Fabulous Forethought.” Science Teacher. (Jan 2007): 24-27. Academic Search Premier. Web. 15 May 2010.

Spano, Sedra. “Adolescent Brain.” Youth Studies Australia. 22.1 (2003): 36-38. Academic Search Premier. Web. 15 May 2010.