Aesthetically Teaching Part II: Don't Forget the Watercolors

“I am so totally going to Walmart after class and buy me some watercolors.”

The unit is on the argument of whether or not art has a place within society. Plato argued it disrupted our sense of reality with our copies of copies. He believed we ought to be in the business of truth seeking. I walk into my Composition 122 classroom, arms full of another bag of tricks.

“You’re really taking this art thing far, aren’t you?” my husband asks.

“It’s directly related to the textbook!” I defend.

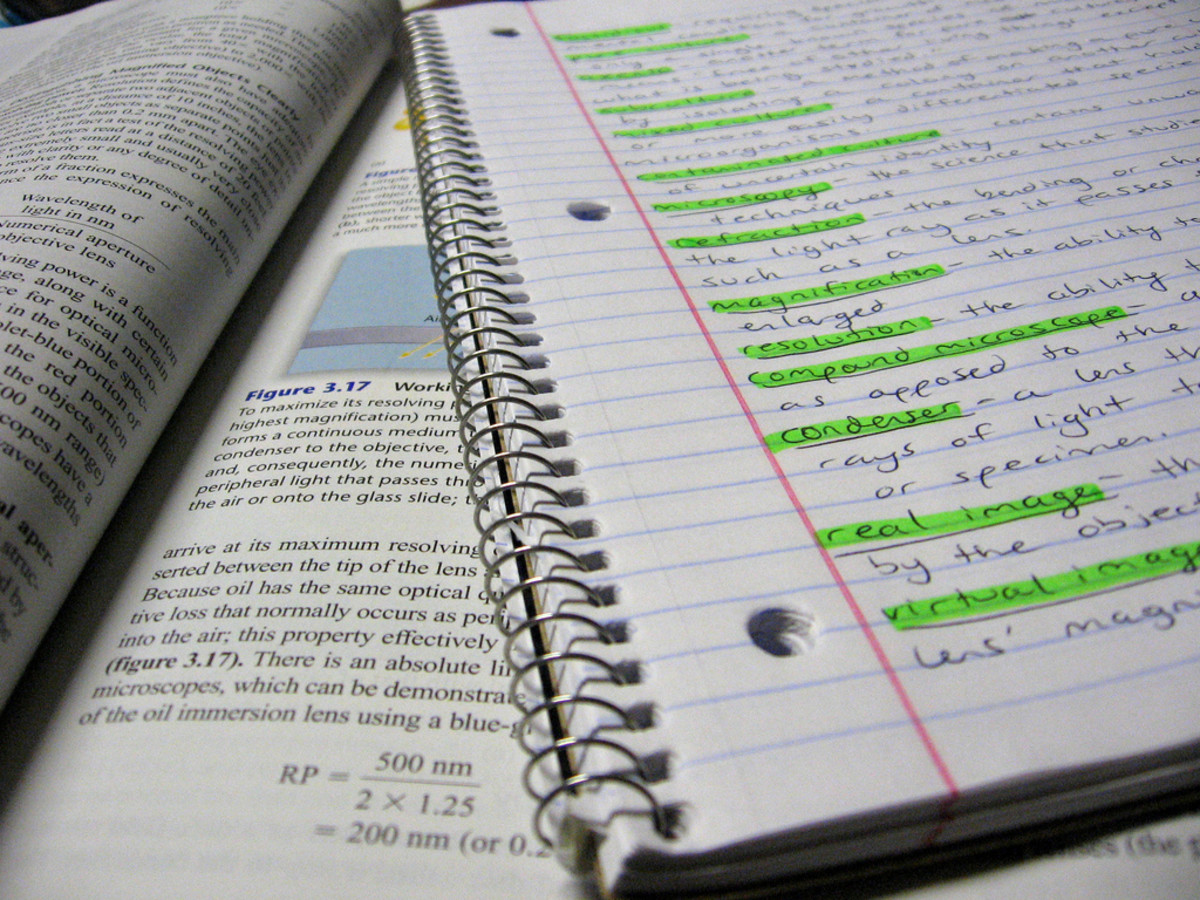

Last week I found my gears spinning on this idea of aesthetic teaching. An actual conscious approach and label for the way I conduct my classes. I think back to all the crazy things I have done for the sake of metaphor and connection making. My house is filled with labeled boxes and Ziplocks—Rock metaphor; Purposes of Argument; Photographic claims of Fact, Value, Policy; Equality & Collaboration . . .For many instructors, a college classroom is a place of lecture and discussion only. For me, it is inconceivable to teach a unit on the argument of art vs truth without including a little bit of hands-on art. But it’s not just this unit. All units lend themselves to a mix of hands-on, traditional lecture, collaborative discussion, and so on.

I start out at the board with a poorly drawn cave and proceed to explain Plato’s famous Cave Allegory: There are people chained within the cave, facing the back wall. They are aware of those around them, but they cannot move from their places nor look behind them. Walking in a circular fashion behind them are people whose only purpose in life is to walk. They are holding objects above their heads. The light from the mouth of the cave filters in. The people chained to one spot watch the back wall, and as is the way with all emergent civilizations, they begin naming the recurrent patterns in front of them. They are seeing the shadows of the objects that are being held by those behind them, but they are not aware of why they are seeing what they are seeing. Bunny. Fish. Bear. Language emerges.

One lucky individual breaks free from his chains. He sees the objects and realizes the shadows he helped label are only imitations of the real objects. He is awe-struck. But what’s this? (Dramatic pause for effect) Is that a light of some kind? He crawls out of the cave and is momentarily blinded by the sunlight. Disoriented, he stumbles about. What? What is this? Why . . . that there looks a lot like the shadow of the bear . . . and look here, could that be a fish? For Plato, this was the highest level of understanding. This was Plato’s Forms. The newly enlightened individual feels compelled to share his knowledge. He runs back into the cave. But light to dark, he finds he is again blinded and stumbling in his excitement. By the time he reaches the others below he is almost incoherent. They dismiss his ramblings as senile nonsense. Copies of copies, is what Plato believed art to be. The shadows were like paintings of trees—the object being held behind those chained represented the phenomenal tree. The one we can feel with our hands. But why is it, Plato pondered, that no two trees are alike and yet we call them both trees? Is there a perfect Form of a tree upon which our phenomenal tree was created?

I tell my students the movie The Matrix was also based upon this concept, that the Trilogy takes Neo through the cave. He becomes physically blinded by the end of the Trilogy so he can see the reality of The Matrix—the Forms. Next, I move on to color, and we examine paint blotches. What they identify as purple, red, and pink are truly lavender, burgundy and peony. Finally, I bring up the word “chair.”

“Define it.”

“Something you sit on,” the gentleman in the back with the unkempt hair offers.

I sit on the desk. “Have I turned this into a chair?”

“It has four legs,” the young woman to the right revises. Now we are moving.

“What are you sitting on? Look down.” They all agree they are sitting on chairs, but they sit upon computer chairs with only one leg and multiple fingers with wheels attached.

“It has to have a back,” another shouts out.

“How ‘bout a stool?” I ask.

“No, it’s a stool.”

“How do you know?”

“It’s higher . . .”

I pull out six different pictures of chairs. We all agree that they are chairs, but no two are alike. Plato would say this is because no one chair is a perfect representation of the concept of chair, but in order for man to understand “chairness” there must exist somewhere the perfect Form of chair.

The room feels heavy. The mental exertion is weighing on them. It’s time to move on to poetry and bring this randomness back to the theme of argument. Language is imperfect, but in order to communicate with one another, we must rely on the illusion of concepts. Warrants are those implicit concepts which are not verbally conveyed but are no less powerful. If I understand that the word “midnight” carries with it the concept of darkness, and the concept of darkness carries with it an emotion of foreboding, I can manipulate my audience with use of its term. I can make them feel without asking them to. “Midnight.” I read them a poem by Louise Gluck.

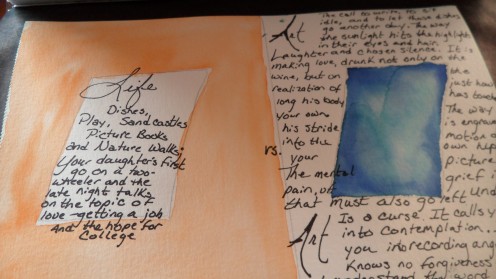

“Think of two words that define you,” I ask. “Are you both a student and a wife? A father and a husband? An adult and a child?”

I pull out the remaining props—watercolors, sketchpad, paintbrushes, a filled water bottle, egg coloring cups, paper towels, and thin-tipped permanent markers.

“Take a sheet of the sketch paper. Draw a line down the middle. On the two sides of the paper, draw a shape—it can be a square, a circle, a heart—anything. Make those objects the same size. On one side, paint the object. On the opposite side, paint around the object and leave the object blank. Now for the words. Write within the blank spaces. Make your dichotomies come alive. I will not read them if you don’t want me to, but humor me. Be good sports.”

Slowly they begin. They look childish and shy. “I’m not an artist,” I hear them whisper.

It’s the kind of day where I give them permission to leave early—instead, fifteen minutes past the end of class, my room is full of grownup students, ages 18-27, watercoloring their images onto the small pages of sketch paper. I feel grateful for their willingness to push through the awkwardness of the moment.

Aesthetic teaching does not mean you have to haul along markers and paint to every class, but it does mean finding ways to bring concepts to your students on a personal level. Lecture is still valuable. Discussion is even more so—but see what beauty you find when you go that one step further. Admittedly, not everyone in the class was touched by the activity, and that’s okay. Those few who weren’t might find my next activity more meaningful. But as the two girls at the front exchanged happy chatter and planned their trips to the store for watercolors of their own, I knew something had gone right.

Brief Bio:

Jenn Gutiérrez holds an M.F.A in English and Writing. Previous work has appeared in journals such as The Texas Review, The Writer’s Journal, The Acentos Review, Antique Children, and Verdad Magazine. Her 2005 debut collection of poems titled Weightless is available through most online book outlets.