- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Endangered Species

African Forest Elephants: Rumble In The Jungle

The Third Elephant Species

Introduction

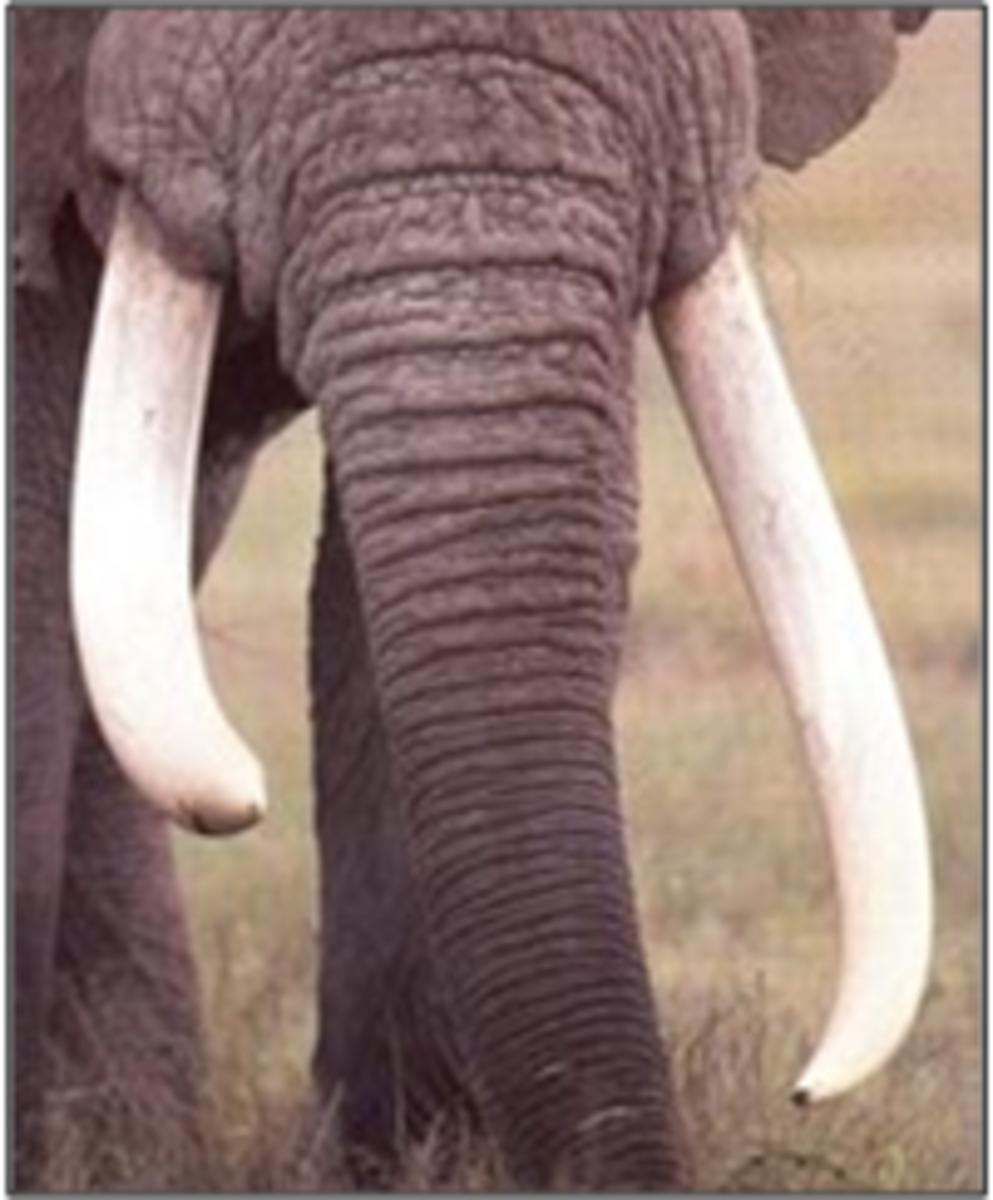

Deep in the dense and dark rainforest's of Central Africa, lives one of the largest animals that walk the Earth today. Despite their size these beautiful and majestic creatures are notoriously hard to spot. At first glance, they look like slightly smaller versions of the iconic savanna elephants often seen marching solemnly across the plains in the shadow of Kilimanjaro. But in fact, the African forest elephant is a unique species of proboscidean. Normally, they do not grow larger than 12 feet tall at the shoulder, and are further distinguished by their rounder ears. Their tusks are straighter and thinner than the savanna elephant, and also possess a pinkish hue that unfortunately makes them highly prized amongst ivory collectors.

Forest elephants live virtually exclusively in the sprawling mass of flora that covers the Congo Basin; they rarely need to leave it as it provides all the food and security they require. One notable exception though, is the frequent occasions they enter large clearings in the forests known as bais. They are attracted to these comparatively small open patches because they provide the one thing that the forest cannot- salt. This precious mineral is contained in volcanic rocks that lie close to the surface. They arch their heads downwards and blow into muddy puddles to churn up the salt rich mud; they then take a huge mouthful which gives them their valuable salt fix. It’s thought that the elephants require salt to aid in neutralising the toxins that are ingested with leaves and bark; essentially it helps to settle their stomachs. It’s also thought that the salt help with both growth and fertility.

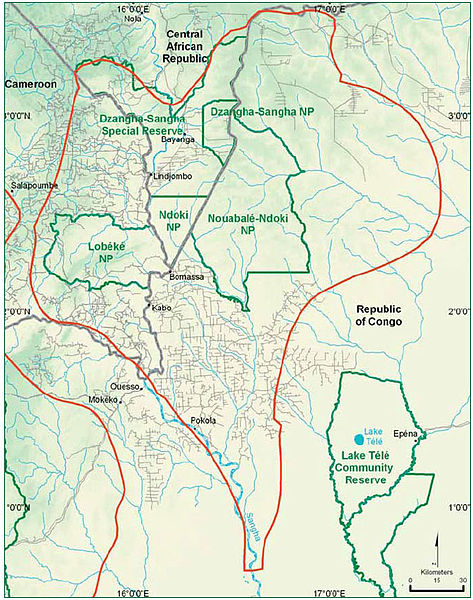

Where is the Dzanga Bai?

Elephants in the Dzanga

The Dzanga Bai

One of the most famous forest clearings in the Congo Basin is the Dzanga bai; it’s by no means the only place where precious salt can be found, but it is one of the biggest and most productive, with as many as 3000 elephants visiting each year to congregate as well as collect the salt.

Forest elephants revere salt so much that there is little they won’t do in order to gain access to the best mineral deposits, bullying is commonplace in the bai. Forest elephants are generally active throughout both the day and night, never sleeping for more than a few hours, due to their need to keep a sharp eye out for predators such as leopards and humans. Although it should be noted that compared to their savanna cousins, they have a rather easy ride when it comes to predators, which is why calves born with disabilities stand a far greater chance of survival in the depths of the rain-forest.

Forest elephants not only travel to bais such as Dzanga to gather salt, but to also meet up with family members whom they may not have seen in months, it’s impossible for forest elephants to congregate in large herds in the forest for obvious reasons, so the bais provide the only opportunity for herd style socialisation, most of which occurs under the cover of darkness. When two individuals greet each other, they make low rumbling noises before gently touching trunks. Such is the importance of Dzanga bai that the local Baka Pygmies call it the ‘village of the elephants.’

Forest elephant families seem to have this uncanny ability to coincidentally arrive in a bai at the same time. But in actual fact, these meetings are carefully planned, as low rumbles can travel for over a mile through the densest areas of vegetation. They essentially have the ability to invite members of their family to meet in a bai over a considerable distance. Some of these calls are so low in frequency that they are totally inaudible to our ears.

Dzanga bai is located within the supposedly safe confines of a National park, but unfortunately poaching continues with 1 in 10 of the elephants that frequent Dzanga being taken every year. It’s saddening but apparently a pair of forest elephant tusks can fetch as much as $190,000 on the black market, so it’s understandable why many local people in particular are tempted to risk being shot by the rangers in order to drag their families out of poverty.

Mother and Baby

Young Elephants at Play

An Irritating Neighbour

Life in the Forest

Forest elephants have an enormous influence on both the shape and richness of the forest, which they exert through their secret wanderings. The most obvious way they do this is by engineering elaborate pathways through the dense vegetation. Over time, their huge feet have manufactured wide highways that link up different food resources, including the bais. These elephant highways are very useful to other animals, including a cousin of ours, the Western lowland gorilla; another endangered denizen of the jungle. The gorillas use the elephant paths as signposts that lead them to succulent fruit which they enjoy as much as the elephants.

As the forest elephants move through the gloom they deposit unharmed seeds in their very own pre-packaged fertiliser, thus creating extensive avenues of their favourite trees. In certain areas, where elephant activity is especially high, grasses and sedges often replace trees, which is a very important part of both the elephant and gorilla diet. It’s no understatement to say that if not for the elephant then the lives of the gorillas would be very different and presumably much harder.

However, the relationship between proboscidean and ape isn't amicable at all, as the elephants don’t particularly like having to share their clearings with them and indeed any other animals, and will regularly chase off anything that hinders their daily routine.

During the dry season, the bais take on a whole different character, because this is the time when the big bulls start to show off; females and younger bulls alike often grow tense when the larger bulls arrive to engage in the annual ritual of sizing each other up, to see where exactly they stand in elephant society. The younger bulls often get quite feisty as they instinctively copy their older compatriots, engaging in ground shaking pushing matches. For the younger bulls there is still an element of playfulness in their feistiness, but for the bigger and older bulls its serious business and injuries regularly occur, often as result of one elephant being stabbed by the other with their formidable tusks.

Elephants in general have the longest gestation period of all mammals; an incredible 22 months which means that it can take a long time for a population to recover after decimation. Moreover, females only produce one calf every three to four years, but this lengthy time interval allows the mother to devote all of her attention to her offspring. Elephants, being intelligent creatures like humans have to learn many of the complex tasks that elephants normally do, such as using their long and dextrous trunks to eat, drink and wash. A calf also needs to learn which foods are safe to eat and also the importance of salt and how to extract it.

Calves weigh about 230 pounds at birth, and right from their first breath can stand and move around freely, which is absolutely essential to avoid predation. The calf suckles using its mouth, holding its trunk over its head. Its tusks start to emerge at around 16 months old and will continue to suckle from its mother until it’s between 4 and 5 years old, before it is finally weaned off.

For females living in a family group, that contains males as well, the arrival of a new calf is always a source of great interest and happiness. They take it in turns to guard and watch out for the newborn. If a predator should approach for example, they all form a defensive circle, keeping the infant at the centre for protection.

Elephants Under Threat

More on Forest Elephant Conservation

- Update Your Browser | Facebook

Support the ongoing work of Andrea Turkalo on Facebook. - African Forest Elephant – Saving Wildlife - Wildlife Conservation Society

African forest elephants, found mostly in Gabon and the Congo, are endangered due to habitat destruction and illegal hunting. The WCS is studying the habitat needs and ecology of the African elephant and working to expand protected areas. - The Elephant Listening Project

The Elephant Listening Project applies new techniques for recording and analyzing forest elephant vocal communication. Low frequency (infrasonic) elephant calls travel long distances and the team use them to study the elephants in depth. - Current ELP Team

Meet the team behind the Elephant Listening Project including Andrea Turkalo- a renowned elephant expert and conservationist featured in the BBC documentary.

Conservation and Future

The numbers of forest elephants entering clearings such as the Dzanga are actually increasing, and while this may seem good on first impression, it’s actually as a result of intense commercial logging in the forest, due to a decrease in revenue from offshore oil fields. At present there is more money in logging, thus putting forest elephants under great peril. The intensive logging disrupts the character of the forest and also severely disrupts the extensive path networks, thus forcing them to seek the comparative safety of the bais more and more.

A further problem exists with the fact that ivory is now very much back in demand, particularly in Southeast Asia where it is believed that the ivory possesses medical properties. Unfortunately for forest elephants their tusks are in even greater demand due to the fact they are pinker and denser than their savanna cousins, resulting in a rose ivory, which is especially prised for carving.

As mentioned earlier, the price of rose coloured ivory is astronomical, enough to grant a successful poacher and his family a happy and prosperous lifestyle. Inevitably much of the human threat to the elephants comes from within; even the proud Baka Pygmies who have lived alongside forest elephants for millennia have become increasingly tempted by the lure of a better life. Unfortunately, many pygmies have been forced to give up their traditional hunter gatherer lifestyle as resources in the forest have dwindled. Instead they have been forced into a life of misery, toiling in the fields of Bantu farmers who offer them nothing except alcohol which inevitably leads to the breakdown of their society. You can totally understand why a pygmy or indeed any human living in poverty would take up the challenge of collecting rare rose coloured tusks in exchange for nearly $200,000. I would probably do it, although my heart would be heavy in the process.

The Dzanga National Park does its best to confiscate weapons and generally deter poachers, but you get the impression that they are fighting a losing battle. After all, the Dzanga is located in one of the most violent and politically unstable areas of the world; the ongoing conflicts in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo means that the area gets flooded with weapons of all kinds.

Forest elephants are vulnerable enough in the forest, but they are at even greater risk in the open bais, where they have little defence against the automatic weapons possessed by the poachers. One little shining light of hope for the elephants comes in the form of elephant expert Andrea Turkalo, who is the forest elephant equivalent of Dian Fossey, a tough and determined woman from New York who arrived in the Congo two decades ago without any form of scientific training. All she had was a passion to both understand and protect the forest elephant. In that time she has become one of the foremost elephant experts alive today, to the point where she understands their vocalisations in the same way that you or I might understand a language. Records indicate that poaching decreases whenever Andrea is in the vicinity of the Dzanga, so she resolves to never leave the area unless absolutely necessary.

I hope that the likes of Andrea and the people of Dzanga National Park can keep their forest elephants safe, but the fate of the third largest land mammal hangs precariously in the balance. They inhabit a huge area, covering some 2 million square miles, and yet there may be as little as 125,000 left, with the number continuing to fall each year. If they pass into extinction, then the Congo rainforest will never be the same again in more ways than one, and it may have knockdown effect on other animals including the gorillas and human societies such as the Baka. Let’s hope that that never happens.