- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

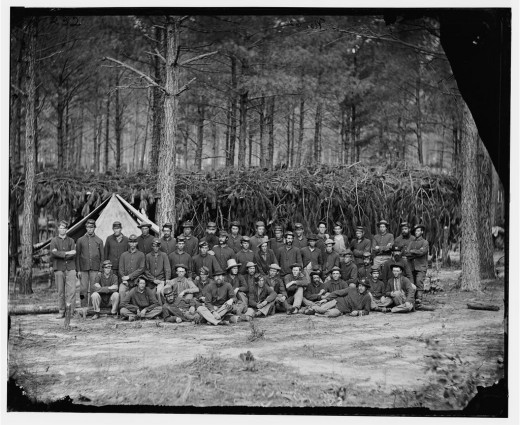

American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life on Campaign 3

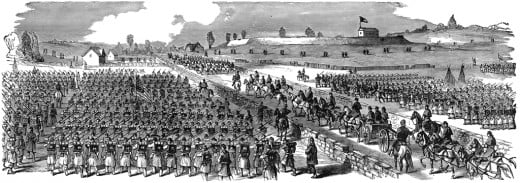

Army On The March

An Army on the march can be thought to consist of distinct Groups or Bodies:

1) The Advanced Guard

2) The Main Body

3) The Rear Guard

The Advanced Guard

The Advanced Guard was a force that was detached from, and in advance of, the Main Body, (to be described later) but acted with reference to it. “Advanced Guard” was a term used for any body of troops that was separated from the Main Body, whatever might have been its strength and composition, and whether it maintained a position or was on a march. Its purpose was to place itself between the Main Body and the presumed location of the enemy in order to keep the enemy ignorant of the Army’s strength, intentions, and position, all of which was critical to the survival of the Army.

For a large Army, the Advanced Guard was to be composed of all Arms (Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery). The strength of the Advanced Guard was to be significantly proportionate to that of its Army. It needed a good degree of strength as the Advanced Guard might have been needed to resist the enemy alone for a lengthy period of time and must have dispersed some of its strength to occupy advanced posts along its front and on its flanks in order to keep watch for, and anticipate, enemy movements. The proportion of the Advanced Guard to its Army varied from 20% to 33%.

If the Army was large, and the countryside was such that many advanced posts were required (mountainous and/or heavily forested regions, many road networks, etc), the larger 33% proportion was necessary, as perhaps a third or half of the Advanced Guard’s strength was required to occupy these advanced posts. In a small force (perhaps Brigade-sized) of two or three thousand men, 20% was usually the most that could be spared for an Advanced Guard, and might consist of only one or two Arms.

To reiterate, the purpose of the Advanced Guard was to keep the enemy uncertain as to the Army’s strength and movements. To do this, it must have been constantly between the enemy and the Main Body, and been strong enough, in offense or defense, to thwart enemy attempts to gain information on the Army or foil enemy attempts to assume threatening or observatory positions. An old military axiom, "a sword opportunely drawn frequently keeps another back in its scabbard“ was used to accurately describe the role of the Advanced Guard.

The Main Body

The Main Body was the remaining force of the Army that was not detached for duty as Advanced Guard or Rear Guard. Generally this group was the largest of all three groups, and supported either or both of the other groups as was deemed necessary for continued security and/or survival of the Army.

The Rear Guard

Last on the order of march was the Rear Guard, if utilized. As the name implies, the Rear Guard was the force charged with protecting the Army’s rear areas. The Rear Guard was usually formed if the Army tried to stay ahead of the enemy, either in retreat or in advance. In case the enemy was close upon the rear of the Main Body, the Rear Guard was there to meet and delay them. If the Army advanced directly upon the enemy, however, a Rear Guard was not often thought to be necessary, except perhaps if there was some concern about unaccounted-for enemy forces that could make a dash upon the Army’s rear.

As a detached force, the Rear Guard was, thus, an Advanced Guard by definition. It needed to interdict any enemy forces seeking information on the Army, or otherwise to put the Army at a disadvantage. It needed to be of sufficient strength to fight alone against enemy forces for extended periods of time, and to occupy outposts to warn of enemy activities against the Army. It needed to field forces from all Arms, or as many Arms as was possible, to better achieve these objectives. Since this force was meant to guard the most vulnerable part of the Army (its rear), it was referred-to specifically as Rear Guard, rather than Advanced Guard.

The Rear Guard conducted its operations in a direction other than the Army’s route of march. Therefore, the distance between the Rear Guard and the Main Body increased every moment, leaving the Rear Guard more and more isolated. The Rear Guard, thus, needed to be alert against being outmaneuvered or surrounded by enemy forces, and needed to fight alone for a longer period of time before reinforcements (if any) could arrive. Often, a “running fight” could ensue, wherein the Rear Guard would need to deploy, fight, retreat, re-deploy, fight again, retreat again, etcetera.

Chain Of Order

The army moved in an established order. Units that held lead positions the first day assumed the last positions the next day, and moved up the chain of order each succeeding day. While commanders could, and sometimes did, vary the positions of the units and the orders of march due to circumstances, this order was typical:

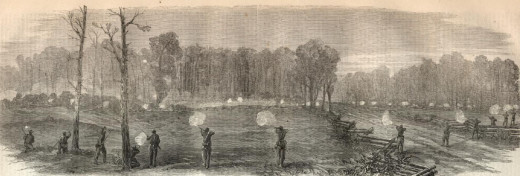

Cavalry

The army was usually preceded by Cavalry, which was present (or needed to be present!) to some degree on all sides of the army. Its greatest concentrations were in areas nearest to the expected locations of the enemy and to the areas where the army needed suitable forces of guards (ie. around the wagons). The Cavalry possessed its own artillery, which gave it greater firepower. This enabled the Cavalry to fight more effectively, for longer periods of time, in engagements with the enemy. When the enemy was encountered, the Cavalry spread the alarm to the rest of the army.

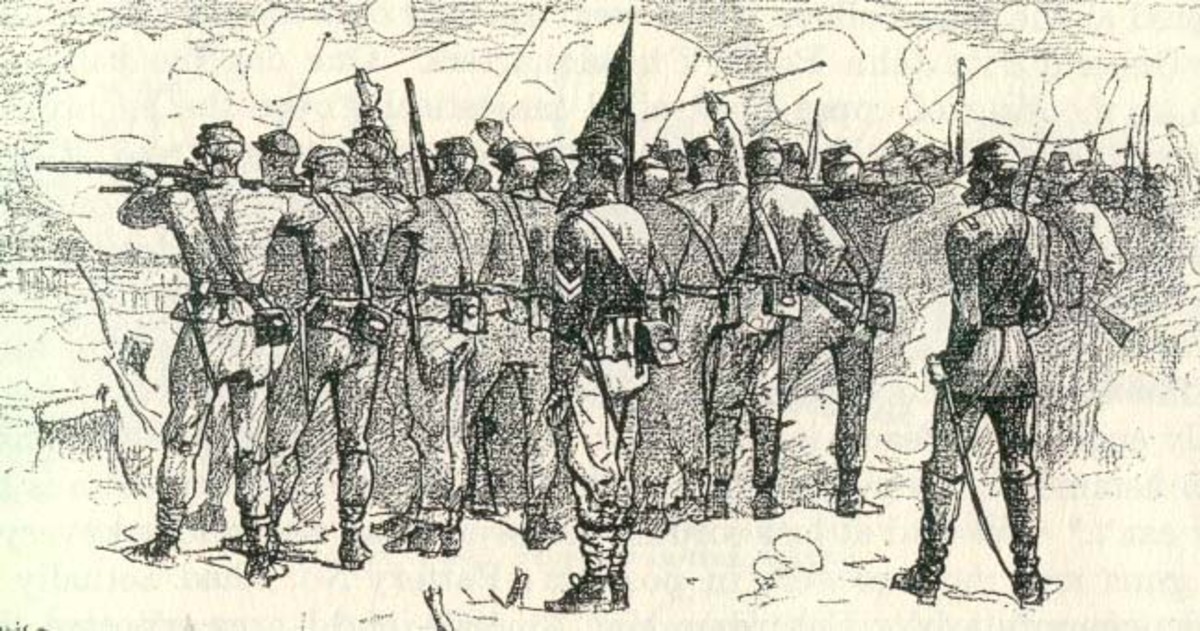

Infantry Skirmishers

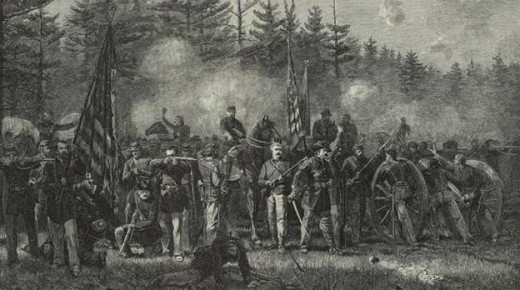

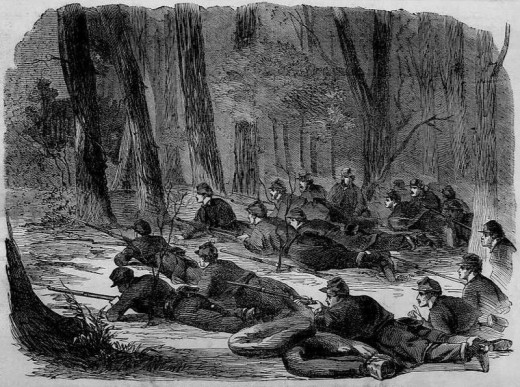

Behind the Cavalry were infantry Skirmishers (often referred to as Sharpshooters). Similar to guards in camp, the Skirmishers were deployed in dispersed order, and were well to the front in order to keep a lookout for enemy forces and to give sufficient alarm. Skirmishers were also out at one or both sides of the army and were known as Flankers. If the enemy appeared at a flank, the Flankers became the advanced skirmish line for the army. Skirmishers were also sometimes deployed at the rear of the army, to keep watch in case the enemy somehow appeared in that direction.

For the infantry, two Companies of each infantry Regiment, other than the Color Company, were designated the Skirmisher Companies. When not detailed as Skirmishers, or after they were driven-in or recalled, these Companies regrouped into line of battle and rejoined their Regiment. If occasions called for it, entire Regiments, not just two Companies of each, were detailed as Skirmishers.

Order of March - Regiments / Battalions of Brigade

The first unit in the order of march was an infantry Regiment, less the already-mentioned two Skirmish Companies already deployed. The Regiment marched by the flank, and the commanding officer and staff of the Regiment rode their horses in front of all.

Next in the line of march was the Regiment’s supply wagons. Each wagon was covered by a canopy of canvas, and was pulled by a team of six mules and driven by one mule driver. Each wagon also had a toolbox under the front seat, a feed trough (for the mules) that hung from the rear, and buckets for water and axle grease that hung near the back wheels. The supply wagons carried fodder for the mule teams and officers’ horses, large shelters like Sibley or A Tents if used, clothing, tools like axes and picks, officers’ baggage, extra rations and ammunition, medical supplies, and any other impedimenta thought necessary by the officers. The men needed to carry their own baggage on their persons though, early in the War, there were often enough wagons for transportation of knapsacks at times.

The number of wagons per Regiment varied during the War. Several were allowed at first (probably 10 or more, as at least 1 per Company was acceptable), which dropped to between three and six by mid-War, to even one or none in the last year. Some crafty officers managed to keep more wagons than were allowable under the regulations, however.

In the absence of wagons, the army used mules with supplies strapped onto their backs. Mules were excellent beasts of burden, at least when they behaved. The mules were again led by Mule Drivers, one per mule if possible

Next in the march were the horse-drawn Regimental ambulances. Horses were a bit less irritable than mules (which had the habit to kick), so horses were the better choice to draw wagons that transported wounded and injured men. Each ambulance was accompanied by three men, one of which drove the wagon, and the other two were litter (aka stretcher) bearers. There were two types of ambulances: two-wheeled, drawn by one horse each, and four-wheeled, drawn by teams of two horses each. Like supply wagons, the number of ambulances per Regiment also varied during the war. One to three ambulances was the most common allotment.

Two litters were in each ambulance. Each litter was tightly stretched canvas or cloth over a flat, wooden frame with a long wooden pole on each side. A wounded man, unable to walk with aid, was lifted by the bearers onto a litter. The bearers then lifted the now occupied litter, by the poles, to their shoulders and brought it to the ambulance. The litter and occupant were then inserted into the ambulance. Each ambulance was designed to transport two wounded men on litters. In times of dire need, as many as six wounded men were crowded into a four-wheeled ambulance, which meant not every man could lie down. Under the driver’s seat was kept items such as bedding, food, plates and utensils, candles, and kettles or buckets. These were all for the comfort of the wounded men when the ambulance was in transit to, or arrived at, the treatment centers.

The following Regiment in the Brigade was next in the line of march, with the same organization as the one that preceded it.

Brigades of Division

After all Regiments in the lead Brigade had passed, the supply wagons and ambulances assigned to the Brigade (varied in number) followed. In the early days of the war, artillery was also assigned to infantry Brigades. In those days, the artillery followed the last infantry Regiment of the Brigade, and Brigade supply wagons and ambulances followed the artillery.

After the first Brigade came the next Brigade of the Division, with the same organization as its predecessor.

Divisions

After the last Brigade in the Division had passed, the next in the order of march was the Artillery assigned to the Division. The artillery was cannon, and they were organized as Batteries of four to six cannon each. Two Batteries were the normal artillery allotment per Division. The cannon were hitched to limbers, which were two-wheeled carts, drawn by teams of six horses each. Horses were used instead of mules because horses were generally better behaved while under fire. Along with each cannon was a caisson, a wooden box that carried the ammunition. The caissons were also hitched to limbers and drawn by six horses. The artillerymen not assigned as mounted drivers to their cannon or caisson, were to march behind and beside their cannon. However, they often took turns to hitch rides on the caisson.

Behind the Divisional Artillery came the ambulances and supply wagons assigned to the Division, which varied in numbers.

Next up was the succeeding Division, similar in organization to the first.

Corps Artillery

When Corps formations were used, artillery assigned to the Corps, if any, followed the last Division. This was the Corps’ Artillery Reserve or Brigade, which normally contained two to six Batteries. Corps Artillery Brigades in the Union Army, when first created in 1864, were not widely utilized due to the continued and common practice to disperse artillery to the Divisions. When used, the Artillery Brigades comprised the artillery previously assigned to the Divisions in the Corps.

Next in the order of march came the Corps ambulances and supply wagons, which varied in number.

Artillery Reserve

After the last Corps, the army’s Artillery Reserve (if created) followed. The Artillery Reserve normally comprised four or more Batteries and was under the direct orders of the army commander or his chief of artillery.

Any remaining ambulances and supply wagons trailed behind the Artillery Reserve.

Provost Guard

Behind the remaining ambulances and supply wagons of the Army followed the Provost Guard. The Provost Guard was the de facto “police” of the army. They handled duties like the round-up of unauthorized stragglers and deserters, prisoner incarceration (Union and Confederate), and detention of the army’s law-breakers.

Headquarters and Specialty Units

In among the Army, often somewhat near the headquarters of the Army commander, were specialized units, like engineers, pioneers, sharpshooters, and the headquarters guards.

If natural barriers were expected, or fortifications were needed right away, the engineer units of the army were among the advance units. They constructed ways over or around these barriers or erected fortifications before most of the Army arrived, which thus reduced delays. Otherwise, they usually stayed nearby the army commanders, who could have been nearly anywhere in the order of the march. They were lightly, if at all, armed since their construction duties were hampered by most weaponry. Pistols and short swords were their primary weapons as they were small enough to carry and not get in the way so easily.

Pioneer units cleared trees and brush and any enemy obstructions in front of the main line. They were armed with axes primarily, and often worked with, or alongside, the engineers. Pioneers were often detailed to lead attacks so that they could break up enemy barriers meant to sow disorder in the ranks of the assault force. This prompted others to refer to them, in these cases, as The Forlorn Hope due to the likelihood of severe decimation without the ability to defend themselves.

Sharpshooters were highly trained marksmen needed to eliminate specific and high priority targets, such as enemy leadership and other personnel, over long distances. They were armed with heavy, long range rifles, often with attached scopes for better visibility of their targets. Sharpshooters fought in dispersed formations, very similar to that of skirmishers.

Headquarters guards were units detailed to protect the Army and Corps commanders. These guards saw no combat unless their headquarters came under direct attack or the man they guarded ordered them into action. The size of the headquarters guard could have been as small as a Company or as large as a Regiment, and were either Infantry or Cavalry. Artillery wasn’t considered effective for headquarters guard duty since artillery wasn’t flexible or agile in close quarters combat or in maneuverability as were the other two arms.

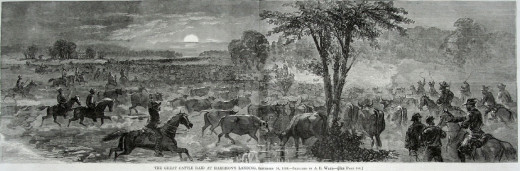

Beef On The Hoof

In the fields adjacent to the roads were often large herds of cattle. This was the army’s “beef on the hoof”; its source of fresh beef for the troops. To expect fresh meat to last beyond a couple of days was not realistic, and the Army was often quite some distance from the supply depots. In order to provide the men with food beyond the normal three day allotment of rations, cattle herds came about. Butchering was done on the march as needed. Units, usually Cavalry, needed to be detailed to guard and drive these herds in order to try to prevent marauding enemy cavalry from driving off the herd for its own uses.

Refugees

Refugees often trailed an army. Fugitive slaves were especially prevalent in this group, as they saw their “attachment” to the army as protection from slave-catchers. This was especially the case during the march of Sherman’s armies across Georgia and north through the Carolinas. The refugee slaves grew so numerous that they proved to be an impediment to the Union forces. Other refugees were displaced white families that begged for food from the troops or scavenged whatever the army cast off during its march. I will go into more detail about refugees in the next article.

Afterword

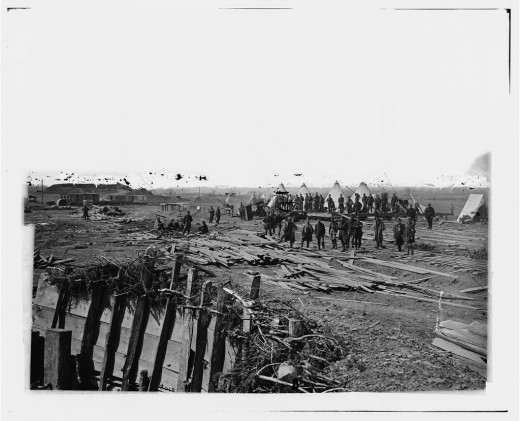

To use one road for the entire army would have caused delays and traffic jams for hours at a time, if not days. Whenever available, other roads were also used. These alternative roads needed to be within a short distance of the main roads to keep the units in supportive distance of each other. This was no easy task given the haphazard road network in nineteenth century America! Frequently, these alternative roads were viable for a certain distance before they diverged too far from the main roads, which forced commanders to merge their units along the march. Nevertheless, an Army on the march was a magnificent spectacle. It often spanned many miles / kilometers of continuous road and kicked up large clouds of dust in dry weather. In wet weather, armies churned roads into quagmires where wagons and their teams almost buried themselves.

The next article in this series is called American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life On Campaign IV.