- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life On Campaign 5

Route of March

Eventually, somewhere along the march, came the need to deviate a little from the standard walk along a well-maintained road. Poor roads and paths, water bodies, and rough country created needs for alternative methods of travel.

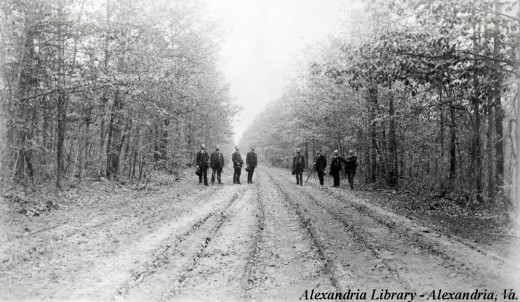

Roads

Roads in the mid-19thcentury varied from little more than narrow dirt paths to cobbled thoroughfares, dependent on the population centers that built and maintained them. State or federally maintained roads that traversed rural areas were the types of roads on which the armies usually traveled. These roads were generally mixtures of sand, gravel, and even seashells. When all compacted, these materials formed a hard, sturdy surface where foot, hoof, and wheeled traffic moved easily, even in most kinds of wet weather.

Locally maintained roads and farm paths were often all or mostly dirt, and these became very muddy in wet weather, which caused treacherous and inhibited footing. After a while, if used often by wagons, these roads were worn down into the earth, sometimes significantly below land level.

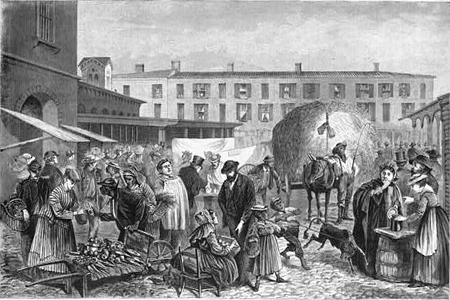

Less common were roads of wooden planks or cobbled stones except in certain cities or major towns. Sometimes such roads connected these population centers. Naturally, roads such as these were coveted by armies of both sides!

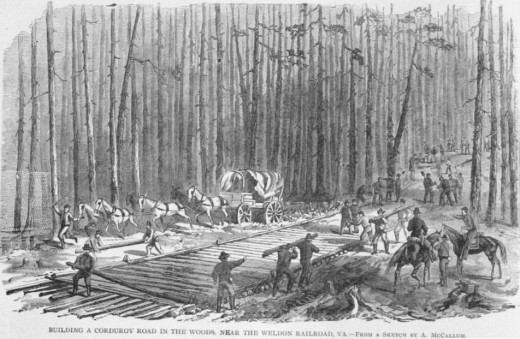

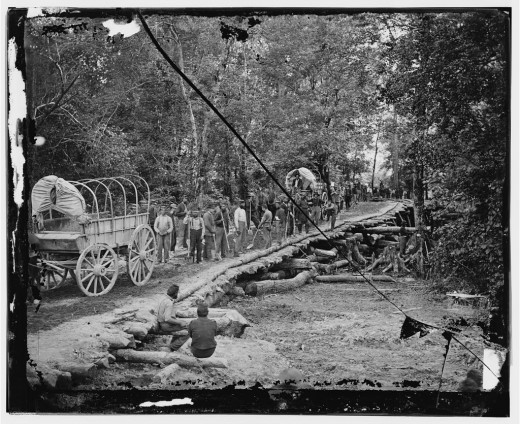

If the ground was very muddy and soft, which impeded the progress of wheeled and/or foot traffic, and if there was the time to do it, the exercise to “corduroy” the route was employed. Wooden planks or logs, called “stringers”, were laid upon the ground, and split logs or planks were secured to them with nails or cord. In many cases, especially in winter camps, split or even whole logs were simply laid onto the ground without the use of stringers. The weight of traffic, that walked or rolled along the logs, sank them part of the way into the soft ground, which partially secured them at least enough on which walk safely.

Water Bodies

Intervening water bodies, such as creeks and rivers, or ground depressions like large ravines and gorges, posed problems that required different means of resolution. The army either crossed through, or crossed over, these natural obstacles to the march.

To Cross Through

The method to cross through water bodies was dependent on the existence of reasonably shallow points in creeks and rivers, where both foot and wheeled travel was possible. These points were called “Fords”. The act, by men and animals, to wade across at these points was thus called “Fording”.

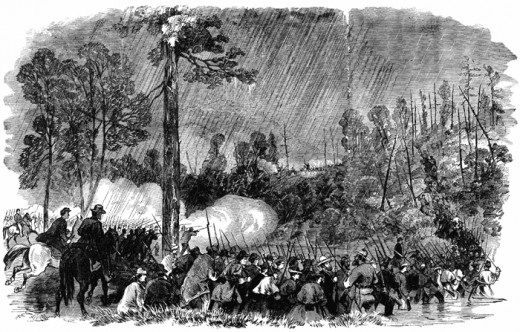

To walk in wet shoes was nearly certain to cause blisters, and leather shrinks when submerged. Wool, like leather, also shrinks when wet. And the black powder in cartridges simply did not ignite when saturated. Thus, if they had time before fording, the men made certain preparations. They first divested themselves of their footwear, even in cold weather. Next, they rolled up their pants legs, or even removed their pants altogether if the water was deep enough. Next, cartridge boxes, and waist belts as well, were removed. The shoes, pants, and/or socks, were then hung from muskets or knapsacks, the cartridge boxes and belts were held up above their heads, and the troops stepped into the water.

In the event of swift currents, cavalry “lifeguards” were often stationed a short distance downstream. Their job was to scoop up men that slipped and fell during the fording and were swept away.

When the other side was reached, the men dried off as best as they could. In the event of cold weather, fires (if allowed) were often kept on the opposite bank to aid the troops in their attempts to dry and warm themselves. After a few more moments in which to re-dress and re-equip, the troops were called back into line and resumed the march. If another water body was expected within a short distance, the troops did not always bother to redress until after the second crossing, which made for an interesting march in the interval!

To Cross Over

The method to cross over water bodies or ground depressions was known as “Bridging”. This became necessary if water ran too deep for practical fording or ravines or gorges were too steep or perilous to march through. The engineers either built a permanent bridge (if one did not already exist or was destroyed) or constructed a temporary bridge. The permanent bridges were called “Trestles”, while the temporary bridges were “Pontoon” bridges.

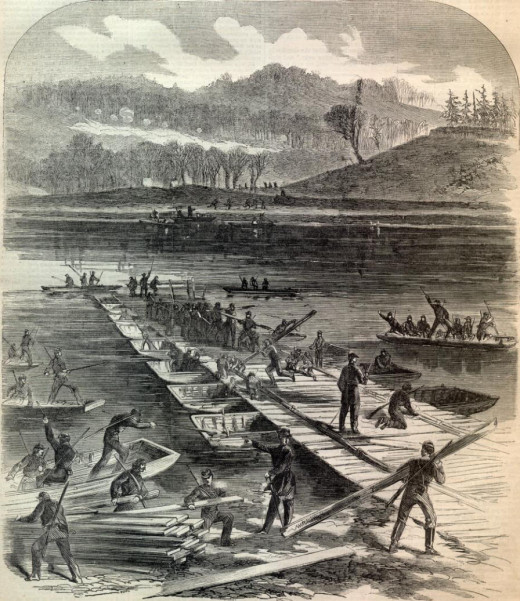

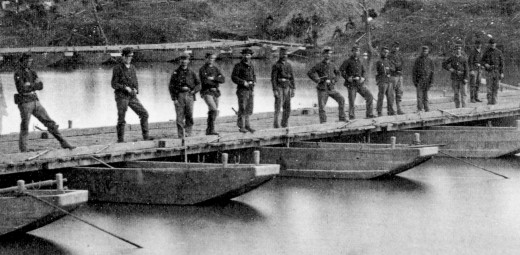

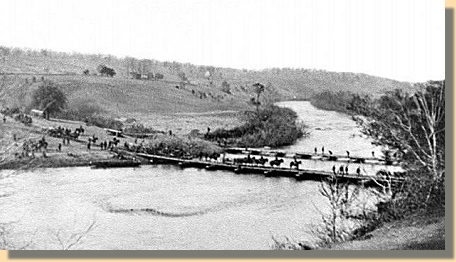

A pontoon bridge, as the name implies, was made up of pontoons. A pontoon was a flat bottomed boat, usually with a wooden frame and canvas or rubber skin. They were hauled on wagon chassis, by horse teams, until they reached a point near the body of water to be bridged. The pontoons were then assembled (if not already), launched with small “crews” of engineers, and paddled down to where they were needed. Each pontoon was positioned perpendicularly to the line of march. When one came into place, it was secured by anchors. Engineers used wooden stringers to connect the pontoon with the shore, and then constructed a wooden planked road upon it. Then another pontoon pulled up alongside, within a few feet / meter of the first, and the process was repeated until the body of water was fully spanned. It should be mentioned that no nails were used. Rope secured all pontoons, stringers, and planking. In this way, the pontoon bridge was more easily dismantled and reused over and over again.

Once the bridge was completed, the army in its entirety marched over as these bridges held very heavy burdens. The infantry units could not march in-step, as this caused such bridges to sway and threaten to break apart, and the pace was regulated to a walk. When the entire army was across, the engineers deconstructed the bridge, unless it was needed to remain in place by design or contingency, and wheeled to the next destination for the process to be repeated.

A more permanent bridge, called a trestle bridge, was built of timbers over gorges that did not have very wide spans, or over fairly narrow water bodies with no water traffic. Several beams or stacks of logs were sunk into the ground or creek bed at regular intervals. Long wooden stringers then connected each interval of beams, and wooden planks or split logs were secured to the stringers, which made a passable plank road. Depending on how close together were the beams for support, these roads were good for foot and most wheeled traffic, and many were held together with nails!

Afterword

Even without enemy activity, a march could be fraught with minor perils or hindrances that delayed, or sometimes stopped entirely, the march. The methods used to overcome such adversities were very innovative, and often ingenious, but there were many that simply could not be overcome.

The next article in this series is called American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life On Campaign VI.