- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life on Campaign 13

Just Before The Battle, Mother

Just before the battle, mother, I am thinking most of you,

While upon the field we're watching, With the enemy in view.

Comrades brave are 'round me lying, Filled with thoughts of home and God

For well they know that on the morrow, Some will sleep beneath the sod.

- Just Before The Battle, Mother, George Root, 1864

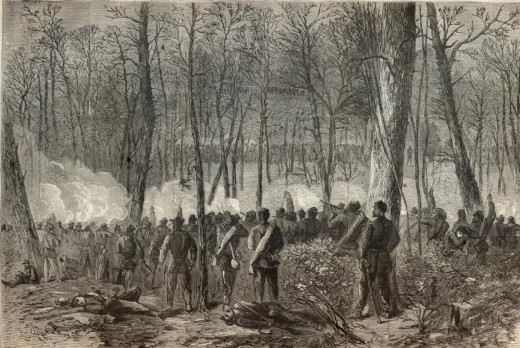

Eve of Battle: Nighttime Maneuvers

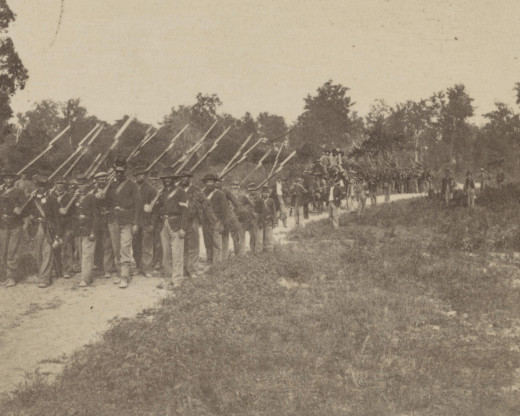

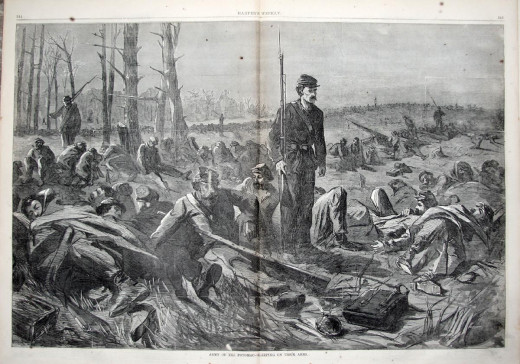

If battle was not to be offered until the next day, then the opposing armies often maintained their positions when night fell. Under cover of this darkness, if the commander desired to realign the army, units found themselves in nighttime marches. This was an extremely difficult feat. Fires were almost certainly forbidden so as not to reveal positions or draw enemy musketry or artillery bombardment. Without fires for illumination, the best hope was for the occasional lantern light from officers or from guides posted to help the units go to where they were ordered, and the light was purposely kept dim. Men that formed for nighttime marches jostled into each other endlessly. During the march, men stepped on each other’s feet or bumped into each other’s backs during sudden halts. When they finally reached the assigned position, unless it was a position far to the rear of the main line, the unit was not allowed to break ranks. The men might have been allowed to stack their muskets and hang their accoutrements from these stacks. Otherwise, they kept their arms and accoutrements right by their sides. They then unrolled their blankets and bedded down in line of battle.

Eve of Battle: Skirmishes

Skirmishes between opposing units, which probably began during the day, almost certainly carried over into the evening. Throughout the night, musket fire from nervous skirmishers and cannon fire from artillery batteries broke the stillness. What generally started as intermittent, individual shots then often increased to near full-battle intensity. More and more troops were drawn into the infectious fray under the belief that general action was in full swing. Eventually, the troops involved either came to their senses, or officers finally gained control of them, and the firing slowly died down. However, it almost never completely ceased and, usually, returned full cycle to peak intensity on and off throughout the night.

Eve of Battle: Sleep and Spirituality

Sleep, if any, for the troops was probably fitful, even if nighttime skirmishes weren’t an issue. Men were usually far too nervous to relax enough for sleep. They thought about what would happen the next day. What would become of them? What would become of their families? The men who tended to sleep the most soundly were the ones who had premonitions of their deaths. Somehow, the certainty seemed to relax them, whereas the uncertainty kept other men sleepless.

Regimental chaplains were usually at hand before battle, to give the men words of comfort or encouragement, and to uplift their spirits. Chaplains often helped the men with such things as letters home, or aided in field hospitals. As was mentioned in the previous series Filling The Ranks, most of the men of this time were very religious, and chaplains served a spiritual need.

The Battle Joined

“I returned to the fight, and our boys were dropping on all sides of me. I was blazing away at the rascals not ten rods off when a ball struck my gun just above the lower band as I was capping it, and cut it in two. The ball flew in pieces and part went by my head to the right and three pieces struck just below my left collar bone. The deepest one was not over half an inch, and stopping to open my coat I pulled them out and snatched a gun from Ames in Company H as he fell dead. Before I had fired this at all a ball clipped off a piece of the stock, and an instant after another struck the seam of my canteen and entered my left groin. I pulled it out, and, more maddened than ever, I rushed in again. A few minutes after, another ball took six inches off the muzzle of this gun. I snatched another from a wounded man under a tree, and, as I was loading kneeling by the side of the road, a ball cut my rammer in two as I was turning it over my head.”

- Oliver Wilcox Norton, 83rd Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1862

Day of Battle

As with the beginning of a campaign, the troops were normally awakened before dawn on the day of battle, usually by jostles and harsh whispers from the Company NCO's.

Once out of their blankets, the troops needed to dress in all clothing and equipment and pack away their shelters immediately. This was easier said than done when still stiff and sore from the ground, in the dark, and when everything is covered with morning dew. Toilets were completed with haste, and with less privacy other than that provided by the covering cloak of darkness. Maybe a few quick bites of hardtack and a few swigs of water were possible for a morning repast, but nervousness and lack of time usually intervened. Any cannon or musket fire, intermittent or regular, only served to increase the troops' jumpiness.

Within moments of the awakening, the men were hustled into their Company formation with roiled stomachs, shaky hands, and drooping eyelids. After a quick roll call and file counts, the Company was marched to unite into its Battalion, which then marched to reach its position in the Army's line.

Battle was just moments away.

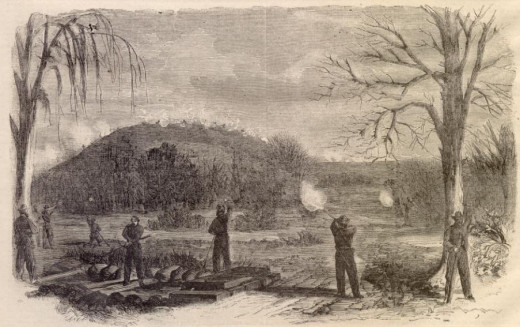

The Ball Opens

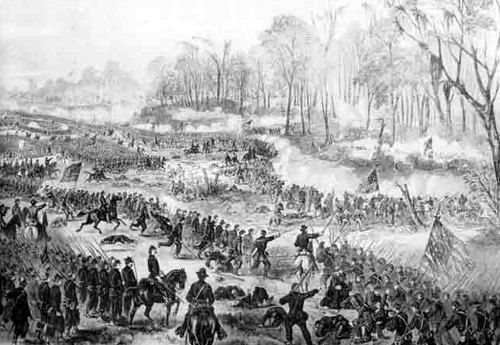

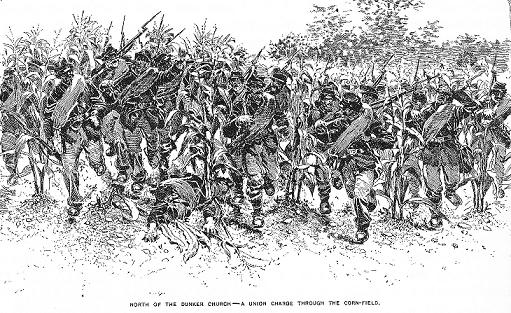

One side or the other eventually began the moves to bring on battle. Cannon fire usually “opened the ball”. The aggressor sought to soften the targeted points of attack with a multiple hour barrage before the infantry or cavalry began their advance. When the attack was launched, the fire of the skirmishers became more general and rapid as each contending unit came into small arms range and sought to gain the advantage. When the main lines then became engaged, the battle intensity increased exponentially.

The fighting soon became chaotic. Dense clouds of smoke were unleashed from musketry and cannon fire, which soon blanketed the battlefield. More smoke from any trees, grass, or houses afire, ignited by the heat and sparks from the munitions and detonations, added to the blindness and confusion. The crash of musketry and the roars of cannon fire and explosions rolled across the field and drowned-out nearly all other sounds. In areas where the weapons fire was not quite so heavy, there were other sounds to ring in the ears. The screams and cries of men and animals with severe wounds, or the shouts of officers who struggled to control their commands, filled any acoustic void.

Troops of both sides also utilized yelling during battle in order to further animate themselves as well as disorient the enemy. Both the “Rebel Yell” (Confederate) and the “Yankee Yell” or “Yankee Hurrah” (Union) are mentioned often in post-battle writings, but a unified description of each yell was often not provided or was not possible due to the many variations of the yells.

A former Rebel cavalry trooper, J. Harvie Dew, attempted to describe both yells, at least from the cavalry point of view, in an article in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, published in 1891, and reproduced in Living History, The Civil War, 1950:

“In a moment more one of the Federal (cavalry) regiments was ordered to charge, and down they came upon us in a body two or three times outnumbering ours. Then was heard their peculiar characteristic yell – “Hoo-ray! Hoo-ray! Hoo-ray!” etc. (This yell was called by the Federals a “cheer”, and was intended for the word “hurrah”, but that pronunciation I never heard in a charge. The sound was as though the first syllable, if heard at all, was “hoo,” uttered with an exceedingly short, low, and indistinct tone, and the second was “ray.” Yelled with a long and high tone slightly deflecting at its termination. In many instances the yell seemed to be the simple interjection “heigh,” rendered with the same tone which was given to “ray.”)

…”In an instant every voice with one accord vigorously shouted that “Rebel yell,” which was so often heard on the field of battle. “Woh-who-ey! who-ey! who-ey! Woh-who-ey! who-ey!” etc. (The best illustration of this “true yell” which can be given the reader is by spelling it as above, with directions to sound the first syllable “woh” short and low, and the second “who” with a very high and prolonged note deflecting upon the third syllable “ey.”)

The other human senses, not just sight and hearing, were also assaulted in battle. The bitter and sulfurous taste of gunpowder was in nearly every soldier's mouth from the ends of the cartridges they needed to tear with their teeth. The acrid odor from discharged weapons smelled like rotten eggs, and it often mixed with the horrifying stench of burned flesh from those that could not escape flames. The troops' fingertips were singed from the fire-heated musket barrels, and were pinched tender when they secured the sharp-edged percussion caps onto the musket cones. Eyes stung and teared from the smoke and sweat that poured into them. Thorny vines and bushes slashed at clothing and any exposed skin which was already badly sunburned and raw. The heavy wool clothing overheated the men as they ran and fought, which sapped their strength and endurance. Throats and mouths were parched dry from the heat and from the inability to quench the ever-increasing thirst. Muscles soon began to stiffen and spasm from the constant exertion, and joints ached. The lungs never seemed able to gain enough air, and it soon became painful to draw breath. Any nearby explosions deafened the men and rocked the very ground on which they fought. Resultant dirt and other debris - perhaps blood and body parts of comrades - showered upon them. Hot blasts of air from narrow misses scorched the skin. Men's heads pounded from the noise and percussion, and the stress of the death and wounds to comrades frayed their nerves and emotions.

Words simply cannot do justice to how thoroughly were the men's senses overwhelmed while in combat.

The Soldier's Experience In Battle

A soldier actually knew little of what happened except in his immediate area, and even that was often very sketchy and incomplete. He probably saw some of his comrades in the line of battle immediately about him. He possibly caught glimpses of the flashes of enemy fire, or of the battle flags, in the distance through the occasional gaps in the smoke, but that was usually all that was ascertained. The time of day might have limited his vision even further. Early morning or evening sunlight was rarely enough light to burn through the battle smoke, and there could often have been lingering mist as well. And amid the din of battle, soldiers might not have been able to hear their firearms go off, orders from officers, bugle calls, or drum beats.

A soldier’s experience in a battle was typically:

- the march into the arena of combat,

- the expenditure of all ammunition during his unit’s tenure under fire,

- the relief of his unit by another,

- the march to the rear for a resupply of ammunition,

- the possible return to the fray.

The length of time the unit was in action varied widely, from about 15 minutes to over 15 hours. During that time, water could have run out, and hunger, thirst, and fatigue could have robbed troops of their senses as they fought for their lives.

Sources of Damage

As the unit’s duration under fire, in any engagement, lengthened, casualties inevitably occurred.

Most casualties were caused by small arms ammunition, such as the oft-mentioned Minie Ball. Of the remaining casualties, nearly all were caused by artillery ordnance. Relatively few casualties occurred in hand-to-hand encounters (saber, bayonet or clubbed musket wounds) due to the infrequency of such combat as well as the troops' preference to shoot, even if at very close range, enemy troops rather than to stab or smash them.

Musket Fire

A musket’s muzzle velocity – the speed at which the ammunition travels the moment it is propelled from the barrel – averaged 950 feet (289.56 km) per second, which equated to 647.43 miles (1,042.41 km) per hour. While this may seem impressive, it is actually somewhat slow, especially by today’s standards, and it must be remembered that this speed decreased the longer the projectile was in flight. When the ammunition struck and entered a body, which caused the projectile to slow down quite suddenly, the bullet began to tumble. The heaviness and inertial force of the bullet caused it to shatter any bones and shred arteries, veins, and other soft tissue in its path. Bits of clothing also tended to cling to the bullet, when it struck, and were carried into the wound. This severely increased the risk of infection. Finally, the relatively soft lead projectiles, flattened a bit upon impact, often remained within the body or, if they did exit, left much greater-sized exit wounds than the entrance wounds.

Troops that were wounded by small arms fire often said they felt they were “punched” by the bullet, which caused them to fall backward, or otherwise in the same direction as the projectile travelled, much of the time. If the projectile exited the wounded soldier, there was a fair chance that it went on to strike another victim, especially if both were filemates in the line of battle. If the projectile already travelled a great distance or was very much slowed by a previous impact, it might not have penetrated its victim. Troops hit by such projectiles often referred to them as “spent balls”.

Artillery Fire

There are too many types of cannon and ordnance to list, but their muzzle velocities ranged from a little over 1,000 feet (3,280 meters) per second to nearly 1,500 feet (4,921 meters) per second, which nearly doubles the velocity of a Minie Ball

Cannon fire was responsible for less than a quarter of all casualties. The actual effect of the cannon, though, came via the psychological effect of the fearsome wounds they inflicted if they did hit the target.

Due to the size of the ordnance and the velocity at which it traveled, cannon fire could literally destroy flesh and bone. Be it solid shot, shell, canister, etc, it was not uncommon for arms, legs, and more, to be torn from the bodies of troops that were the recipients of such fire. When the ordnance found no living targets, the resultant explosions or other impacts put fear into the hearts of the most stalwart troops and often stopped attacks before they began.

Hand To Hand

Extremely few wounds were inflicted by edged or clubbed weapons. However, as with cannon fire, there was the psychological effect to consider also. The sight of enemy troops, at the charge, intent to stab and club, sometimes had a demoralizing effect on those that received the charge, which caused many defenders to run before the hand-to-hand encounters began. The volume of fire from the defenders often prevented such hand-to-hand possibilities, though.

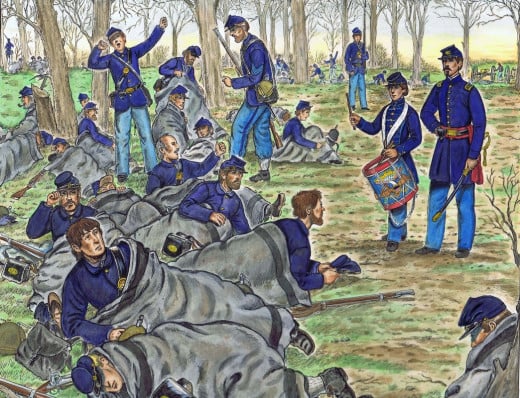

To Close The Ranks

As casualties occurred, each Regiment and, thus, each Company, needed to constantly re-align in order to maintain a proper line of battle. This art was known as “Closing The Ranks”. The logic behind Closing The Ranks was to minimize any gaps within the Company as well as any gaps between the Companies of the Regiment. To do this, each Company’s line of battle needed to keep its breadth for as long as possible. Therefore, if any man in the front rank fell, his place was to be immediately taken by his filemate in the rear rank. If that man fell, which thus eliminated an entire file in the line, both ranks then dressed toward the left, right, or center of the Company, and each man in the rear rank shifted to cover his filemate in the front rank even if a gap then developed. Gaps in the rear rank were acceptable, but gaps in the front rank needed to be closed immediately.

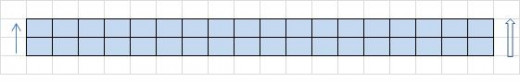

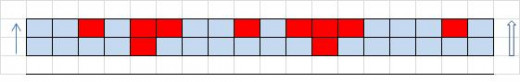

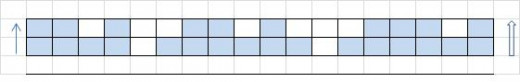

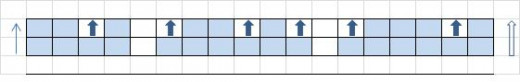

Here is a visual example of Closing the Ranks:

The Company’s line of battle appears here – no casualties have yet occurred:

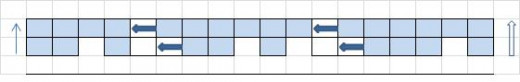

A volley of enemy musketry now strikes the Company, and several men are hit (highlighted in red).

As these men fall, temporary gaps appear in the line (white):

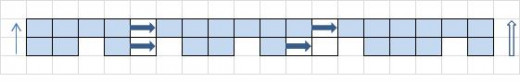

Men in the rear rank now step up to replace their fallen filemates in the front rank:

Dependent on the direction a Company must dress - to the left, to the right, or possibly to the center - the Company will dress to that direction to cover any gaps that resulted from the elimination of entire files. In this case, two files were eliminated.

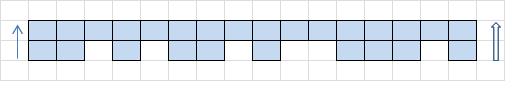

The line has now closed ranks and, thus, maintains most of its breadth with the loss of only two files.

This similar process of Closing Ranks was repeated in all other Companies of the Regiment. Eventually, as casualties mounted, it became necessary for all Companies of the Regiment to close-up on each other in order to maintain Regimental cohesion, and this was repeated on the Brigade and Division-level as well.

Afterword

Throughout any battle, and the War, the stress concomitant with their lives in jeopardy took tremendous tolls on the physical and mental health of the troops. The knowledge of family and friends that fell wounded or killed in any engagement was an even greater psychological toll. Each man’s commitment to his family and country, his religious beliefs, and the comrades around him determined whether or not he successfully endured such horrific trials as that of battle. It is only a surprise that so many were able to bear such a burden as well as they did, since so few of these men were soldiers by profession.

The next article in this series is called American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life On Campaign XIV.