- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life on Campaign 14

The Fallen

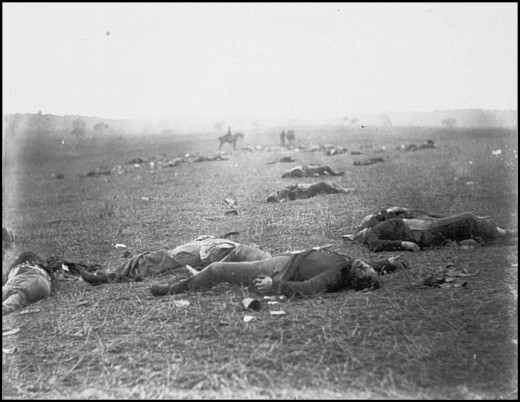

There was no way to fight a battle without resultant damage. In the American Civil War, the human toll of battle was devastating. It was not uncommon for an army to suffer total casualties that exceeded 20% of those engaged.

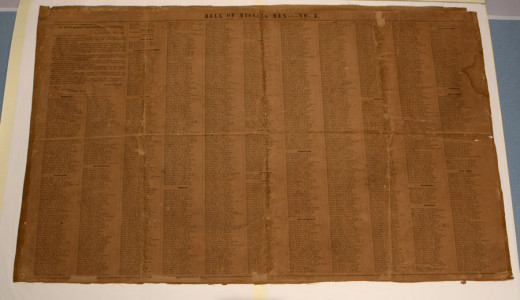

Casualties suffered in battle were somewhat haphazardly accounted-for during the War but, in general, they were categorized into four succinct groups: dead, wounded, captured, and missing.

The Dead

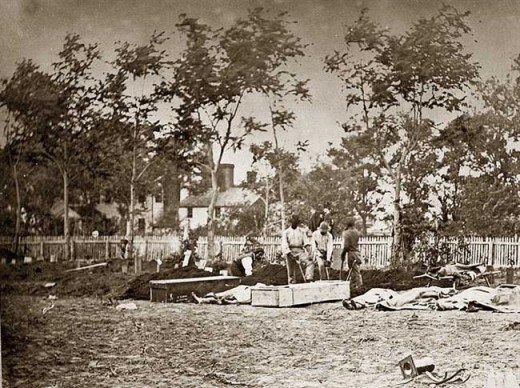

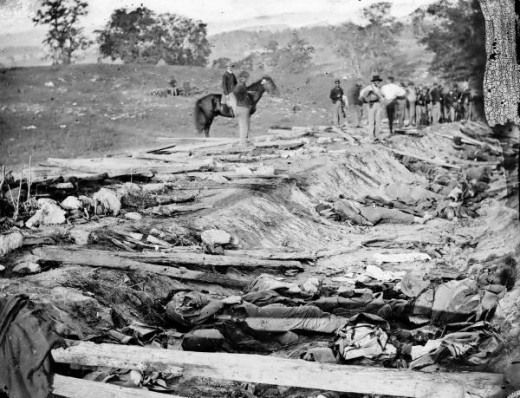

The dead were those that were killed outright in the battle or died sometime during or shortly after the battle. If killed, a soldier’s body often laid on the field at least until combat ended, and generally longer. If battles and maneuvers were almost continuous, as was the case during 1864-65, it was not uncommon for the dead to remain on the field for weeks or even months.

If the body lied, at anytime, behind enemy lines, his valuables and belongings were probably stolen by enemy troops. It was not uncommon for rebel troops to take footwear, food, firearms and accoutrements, valuables, and even entire uniforms from Union dead. If the body lied within friendly lines, items were still often stolen from him – robbers existed in the armies of both sides - but, in general, his body remained at least clothed and somewhat well-treated.

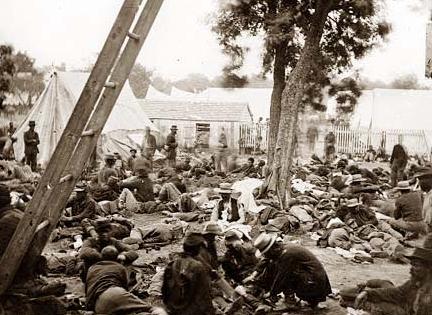

The Wounded

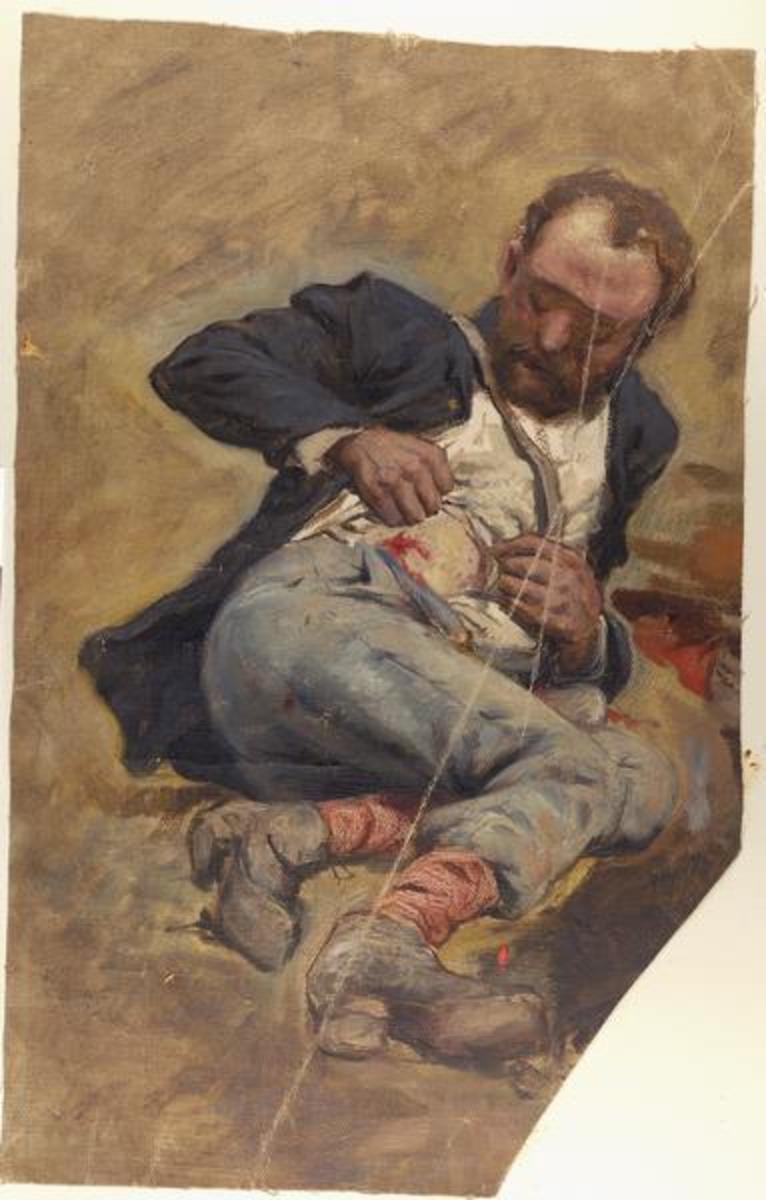

The wounded were those who suffered injury during the battle. Roughly four to six men were wounded for every man killed. When wounded, a soldier often laid on the field for indeterminate lengths of time before friendly or enemy forces reached him, if not already too late.

Once wounded, if still conscious and in possession of his faculties, a soldier’s most common impulse was to see where he was wounded and how grievous the wound appeared. His next step was, if possible, to staunch the blood loss. He might have tied a handkerchief about the wound if it were on a limb or appendage or other extremity. If wounded in the torso, he would have tried to use the handkerchief as a virtual plug to the wound.

It is worthwhile to note that many, who were wounded, eventually died of their wounds, but remained categorized as wounded. Once the casualty lists were compiled, there was often no inclination or time or administrative personnel to update these lists with revised data, if it was even known that the data changed since its compilation.

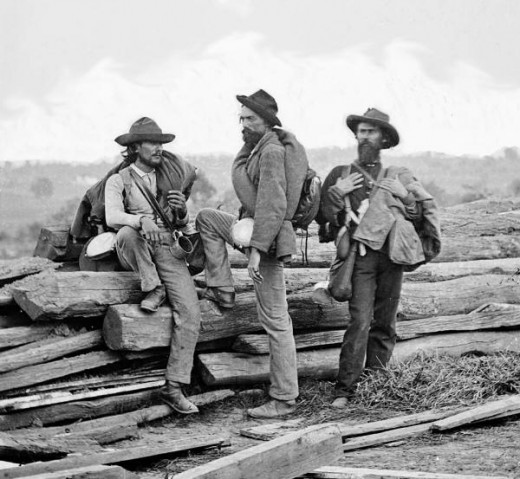

The Captured

The captured were those that were known to be taken prisoner by the enemy, either while wounded or healthy.

If captured while wounded, the soldier was treated somewhat similarly to what was described in the “Wounded” section of this article, though treatment was often delayed. Enemy wounded normally waited a while for medical care until the wounded of the captors’ force received attention.

If captured while healthy, a soldier was immediately relieved of his firearm and any other weaponry that was immediately visible. If the prisoner was captured in an area of the field that was still close by the combat, the enemy was probably still embroiled in the fight with the captured man’s comrades. Therefore, the enemy often did not arrange for a suitable number of guards (if any) to leave the line of battle and escort away the prisoner. In these moments of confusion and uncertainty, the enemy could have done little beyond order the captured man to the enemy’s rear lines. It was the hope or expectation that the prisoner obeyed, and soon met rear-line troops and/or the Provost Guard which would have taken the responsibility to guard him from there. Without an immediate guard detail, however, the prisoner often avoided enemy notice and made his escape, either to rejoin his forces or to desert the army altogether.

In many cases, the risk of getting shot (by foe or accidentally by friend) in any escape attempt was too great to consider, so the prisoner either proceeded on his own, or was hustled under guard, to an area safely behind the enemy’s front lines. Once beyond the immediate combat, the prisoner was relieved of his cartridge box, along with any other ammunition, and his waist belt (with suspended cap pouch and bayonet scabbard). If the bayonet wasn’t already surrendered as part of the firearm, it was surrendered as part of the scabbard on the waist belt. He could also have expected his captors to search through anything else he had, such as the haversack, canteen, knapsack, and blanket roll. At least a partial search of his person probably occurred as well, in the trouser and blouse pockets, in the overcoat pockets, under the cap, in the shoes and socks. The enemy searched for any other weaponry or items of military value. The prisoner might have been allowed to retain these non-weapons items unless, of course, any of his captors wanted them. Dependent on how rough were his captors, the prisoner could have suffered the theft of his valuables and personal effects, and even the theft of some of his uniform, especially footwear.

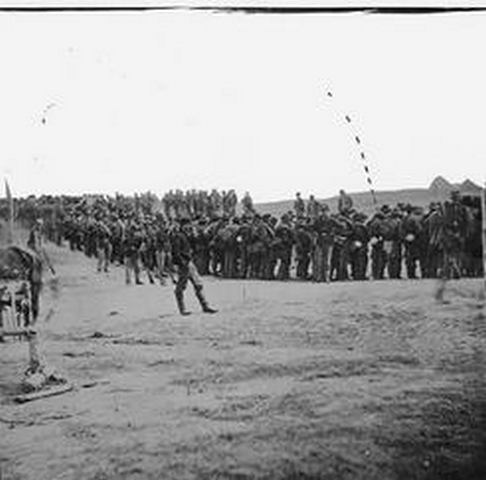

Eventually, the prisoner was transferred, by the capturing unit, to the enemy’s Provost Guard and securely incarcerated someplace. His name and unit were recorded, and then he was interrogated.

If the battle was extremely fluid, it was possible for recently captured troops to be abandoned by their captors, or otherwise escape or be freed, at the approach of friendly forces. Otherwise, the prisoner remained in captivity on the field until he was escorted well into the interior of the enemy’s territory to temporary, or permanently established, prison camps.

The Missing

The missing were those who were not present for duty after the battle and were not accounted-for in the other three categories of casualties. The missing men might have suffered one of several different fates.

Many were men who were actually killed in the battle, but were not noticed, and their bodies were not identified afterward. The bodies might have been obliterated by fire or by extreme wounds. The bodies were, perhaps, already buried or otherwise intentionally put out of sight, such as down wells or within haystacks, before their comrades came back. Natural elements like water might have claimed the bodies, and submerged them out of sight, or carried them downriver and/or out to sea. Some bodies were lost to scavengers, such as hogs or coyotes.

The missing men could have been captured, taken prisoner while out of sight of comrades, then perhaps died in captivity and buried with no markers. Prison camp records were often very poorly kept to prevent any written evidence of prisoner mistreatment. Thus the names of the missing might never have been recorded, or were recorded and then later destroyed.

Or the missing men could have deserted when the chaotic battle conditions gave them the opportunity to leave the army undetected. Most deserters were desired and welcomed back home, perhaps due to hardships without them. If they managed to make it back home, they were hidden from the authorities by their families and friends. Many others deserted to the enemy, in the hopes that they could settle forever out of sight and out of the War in the enemy’s territory. Some later joined the enemy army and took arms against their former comrades if they lost belief or loyalty in their original cause, or even grew hostile toward it. Some did so to avoid lengthy captivity as prisoners of war and to avoid the cruel treatment of which many were aware. Other deserters had no available refuge with family or friends, and had no wish to live in enemy territory, but they needed to go somewhere out of sight of their Provost Guard or other authorities. This often meant these deserters were not able to return home and needed to live as fugitives in the wilderness or in unfamiliar towns of civilians that were rightfully suspicious of strangers.

Afterword

With so many casualties of all types, even a systematic method to account for them would have been severely tested. As it was, there was no effective system, so many missing troops were never found, and nearly one in four of the dead was unidentified.

The next article in this series is called American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life On Campaign XV.