- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life on Campaign 16

After his capture, a prisoner’s fate in the American Civil War was varied.

Exchange / Parole

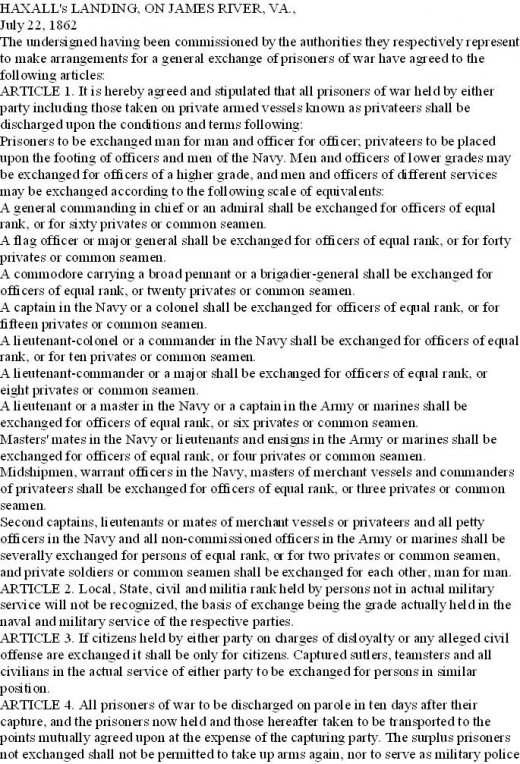

In the early days of the war, there was no policy or system in place for the exchange or incarceration of prisoners. Fortunately the number of prisoners taken by either side at first wasn’t terribly large, and individual commanders often arranged wholesale prisoner exchanges on their own initiatives. However, as the war continued, and the number of prisoners taken rose along with the number of engagements, the issue soon needed centralized and consistent governance.

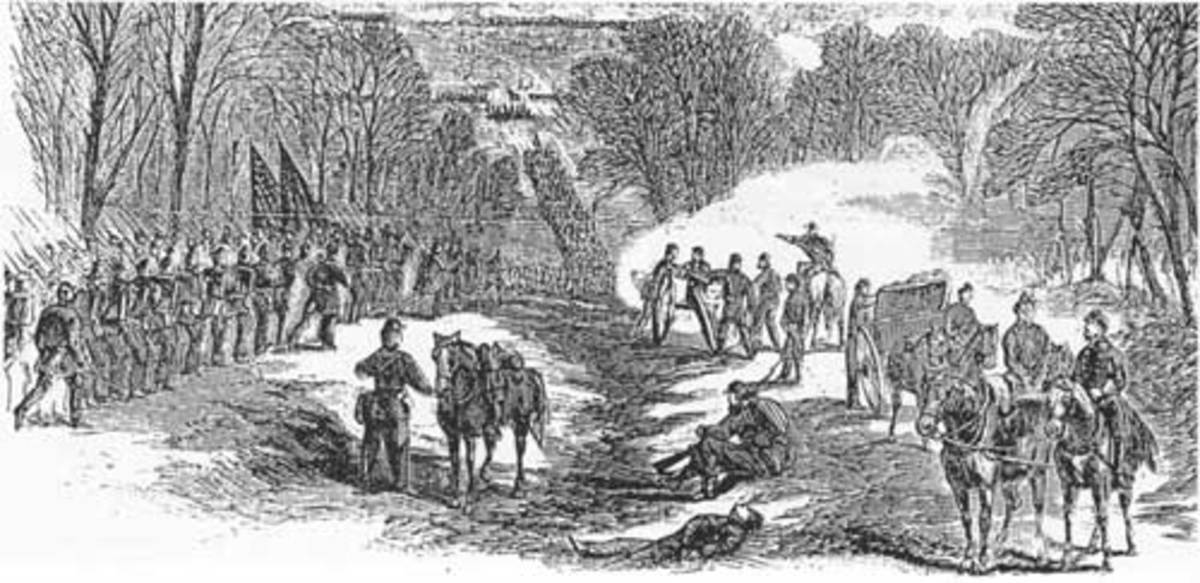

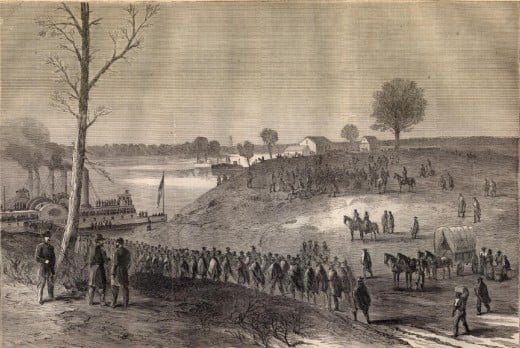

A prisoner exchange policy was formally created by both governments after the first year. The ranks of the prisoners were used as a measuring scale of exchanges. The same ranks were exchanged on a one-for-one ratio, and higher ranks were exchanged for a set number of lower ranks (ie. A major general was exchanged for 30 or 40 privates, a lieutenant for six privates, etc).

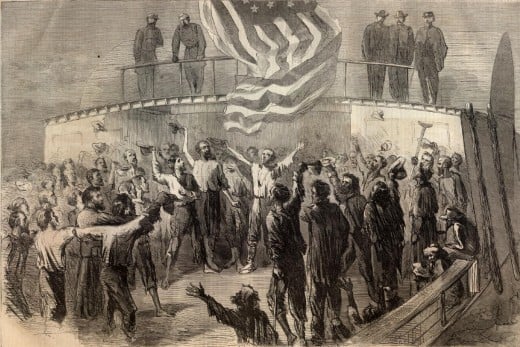

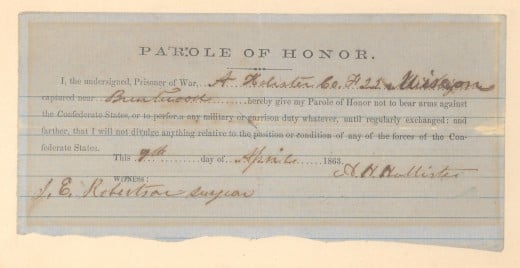

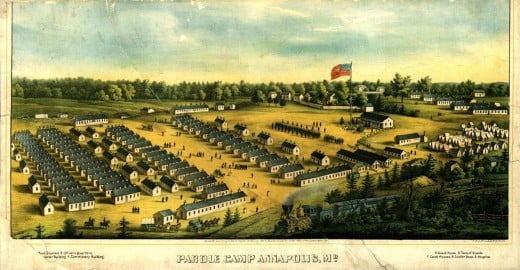

If one side held more prisoners than the other side, paroles were granted. The excess prisoners were sent home under the agreement that they would not take up arms again until they were properly exchanged. In other words, the paroling side needed to receive a like number of returned prisoners before the paroled men could return to active duty. Unfortunately for the parolees, most were assigned to parolee camps after the return to their lines and not allowed to go home. In this way, the parolees were well at hand when the actual exchanges finally occurred, and were then returned to duty.

Incarceration

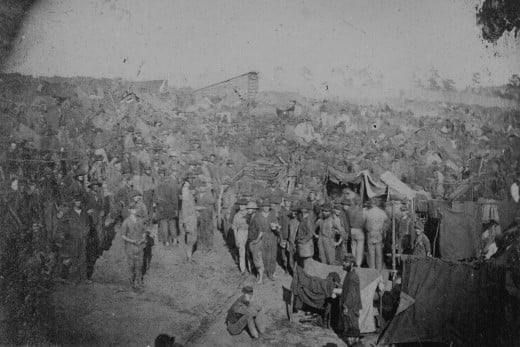

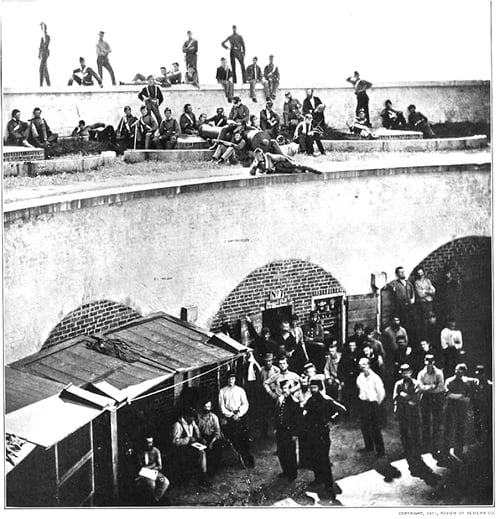

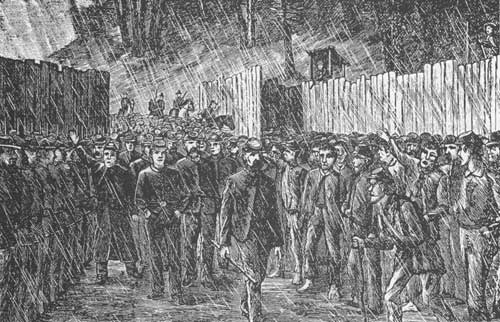

When exchanges and paroles had not yet been arranged, the prisoners needed to be incarcerated somewhere. Jails, schools, former barracks, warehouses, and even open fields were commandeered for prisons. In the few cases where the exchange policy between the two governments collapsed, these prison terms lasted several months or even years.

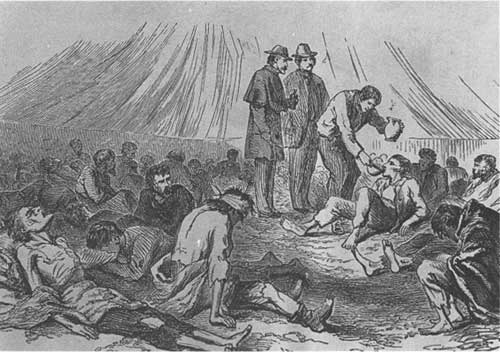

When they reached the assigned prison, captured enlisted men and NCO’s were separated from the officers, and each was quartered in separate facilities of the prison. These prisons, hurriedly fitted-out and usually ramshackle, often became abhorrent. Buildings, already built from poor quality materials and often drafty, became overcrowded and filthy. Tents in the open fields became scarce or tattered, which forced many inmates to live in holes, dug by hand, in the ground.

Prison Issuance: Rations and Clothing

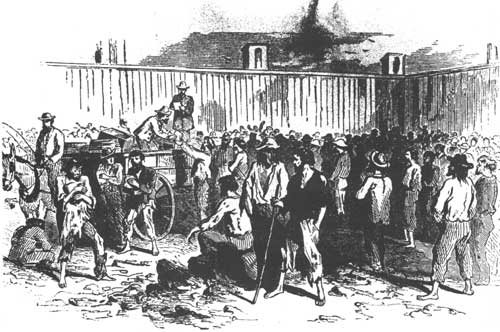

Rations, no better than troops received in the field, became much worse in quality and quantity as the captivity continued. Prisoners often needed to trap and consume rats in order to supplement their meager food allotments. Drinking water soon became foul due to the same practices, used in camp, of latrines that were established nearby the water sources.

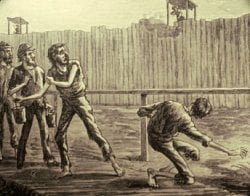

Prisoners sometimes fought each other over food, and they learned to quickly down whatever they were issued to prevent theft. Organized crime and gangs even developed in some prisons where prisoners, looking to improve their lots, preyed upon their fellow inmates.

Clothing was not issued in prisons, so the prisoners were clothed with whatever they still wore when taken, regardless of the condition of the clothing or the seasonal climates of the region.

Sick and Wounded Prisoners

For the sick and wounded, prison hospitals often contained wood framed beds with no mattresses or sheets. Medical care was barely adequate, if there was any offered at all, and the mortality rates of the patients was terribly high.

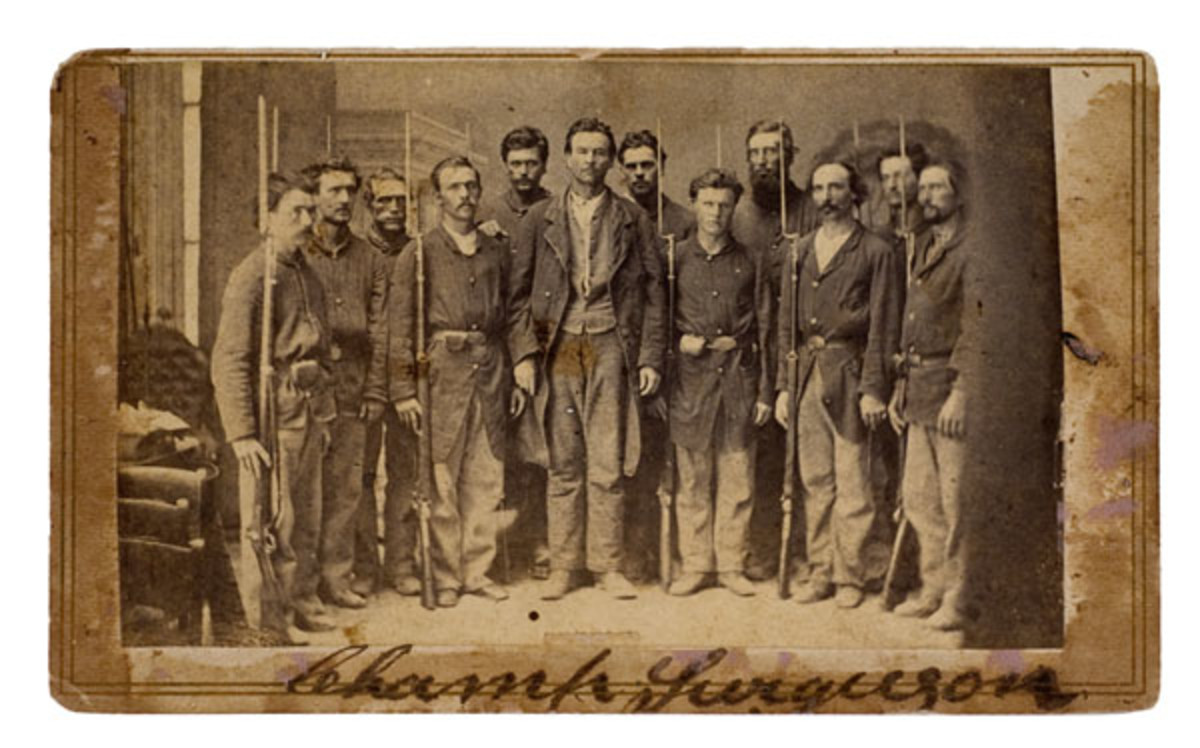

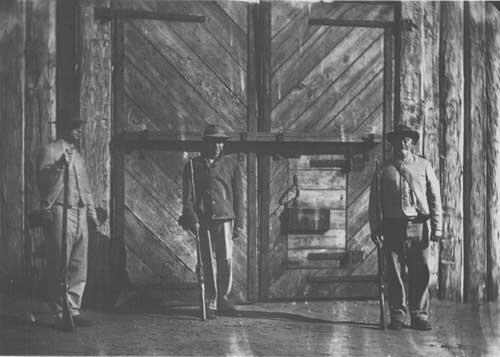

Prison Commandants and Guards

With few exceptions, prison commandants were cruel to the prisoners in their charge. Each believed the other side’s commandants initiated the cruelty, and that retaliation was in order.

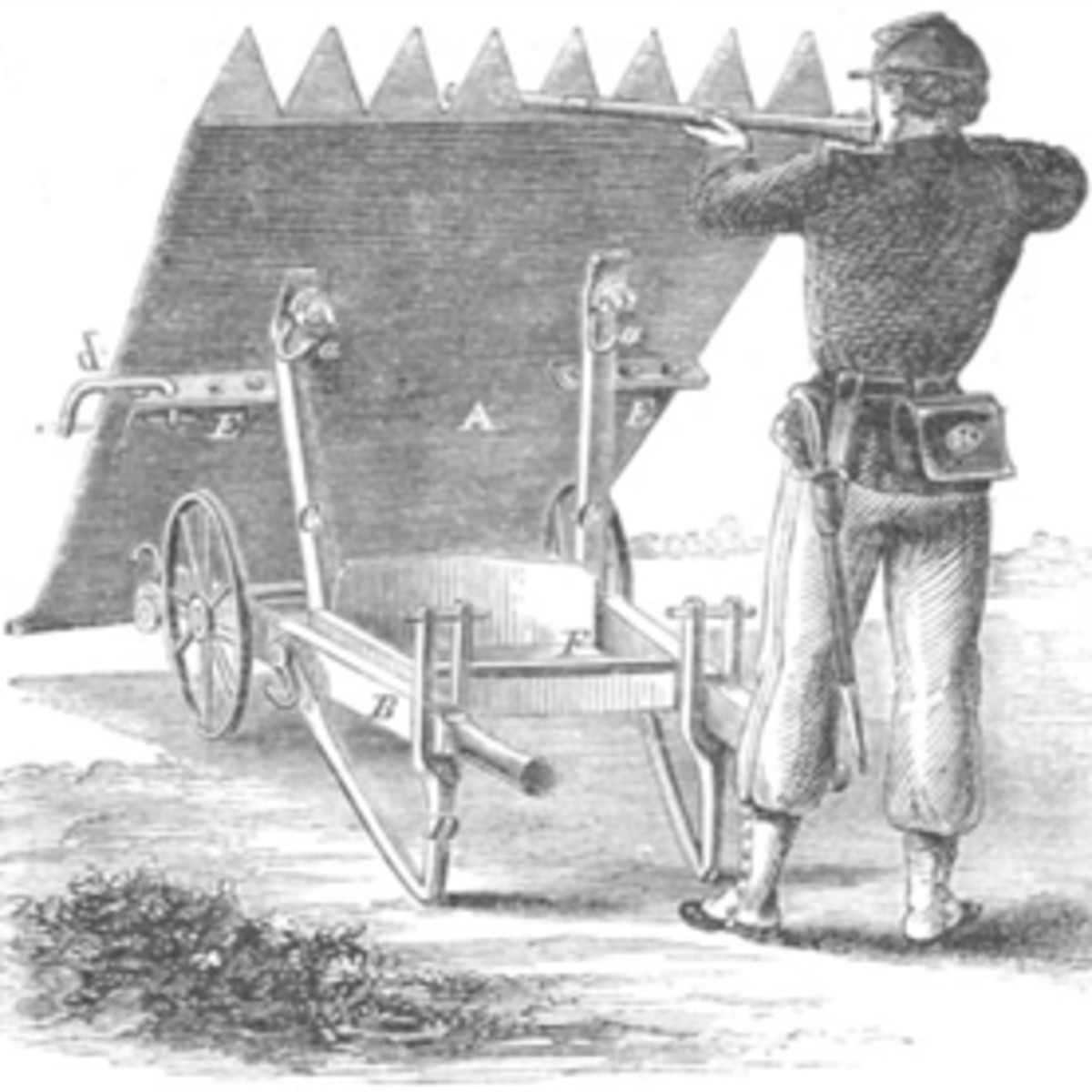

Old or young men, unfit for field service, were often assigned as the prison guards, and they were little better than the commandants in terms of treatment towards the prisoners. The guards of at least one outdoor prison camp erected a small fence, hardly more than posts with top rails, in the interior of the camp, a few feet / a meter from the stockade where the guards patrolled. This fence was called The Dead Line. Prisoners that crossed, or even touched, The Dead Line were liable to be shot by the guards. The guards believed such measures were sufficient deterrents to attacks on them by the numerically superior prisoners.

If the guards were ever veteran field troops, they tended to empathize a little with the prisoners (fellow soldiers, enemy status notwithstanding) and treatment was usually tolerable, if not kind.

P.O.W. Mail

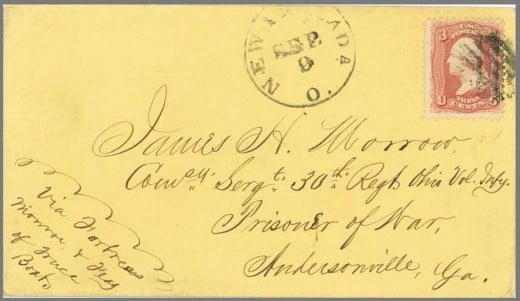

For those Prisoners of War that wished to send mail home, or for those at home that wished to write to a P.O.W., the two processes were fairly similar.

Under the same agreement whereby Union and Confederate prisoners were exchanged, Confederate and Union prisoners were allowed to exchange mail through flag-of-truce ships. Letters to and from Confederate and Union P.O.W.’s were exchanged at designated points, generally City Point, VA for mail from the north to the south, and through Fortress Monroe, VA for mail from the south to the north. In this system, each letter was kept in an unsealed envelope, stamped (or sent “postage due”), and addressed (name, rank, unit, prison). The letter and unsealed envelope were then sealed inside another envelope, which was referred-to as the “outer cover”. This outer-covered letter was then delivered to the exchange point. At the exchange point, the outer cover was opened and destroyed. The letter inside the unsealed envelope was then inspected and censored, where needed, by the agent in charge at this point. When done, the agent returned the letter to the unsealed envelope, sealed it, marked on the cover “Examined”, and sent it on its way to the enemy agents, and thence to the intended delivery point. It is unknown at this time if the letter was inspected by enemy agents after its delivery to them at the designated point. It seems likely, however, that enemy inspections occurred. If so, the envelopes must have been torn open so the letters could be examined, then either resealed somehow, or delivered unsealed to the recipient.

There are many instances where an outer cover was not used. In such cases, the envelopes contained the stamps of both factions, Union and Confederate, and marked by both agents. It is unknown at this time if the envelopes were sealed before going to the designated delivery point. If they were, then the envelopes must have been torn open by whoever inspected the mail at the exchange points, then somehow either resealed or delivered unsealed to its destination point.

Afterword

Due to the bad treatment, escape was never far from the minds of prisoners. Most did not attempt it. Of those who did, most attempts failed due to the wasted condition of many of the participants and the lack of familiarity of the areas in which they traveled after they escaped the prison compounds.

The next article in this series is called American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life On Campaign XVII.