- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War: The Role Of Black Troops

U.S. Coloured Infantry

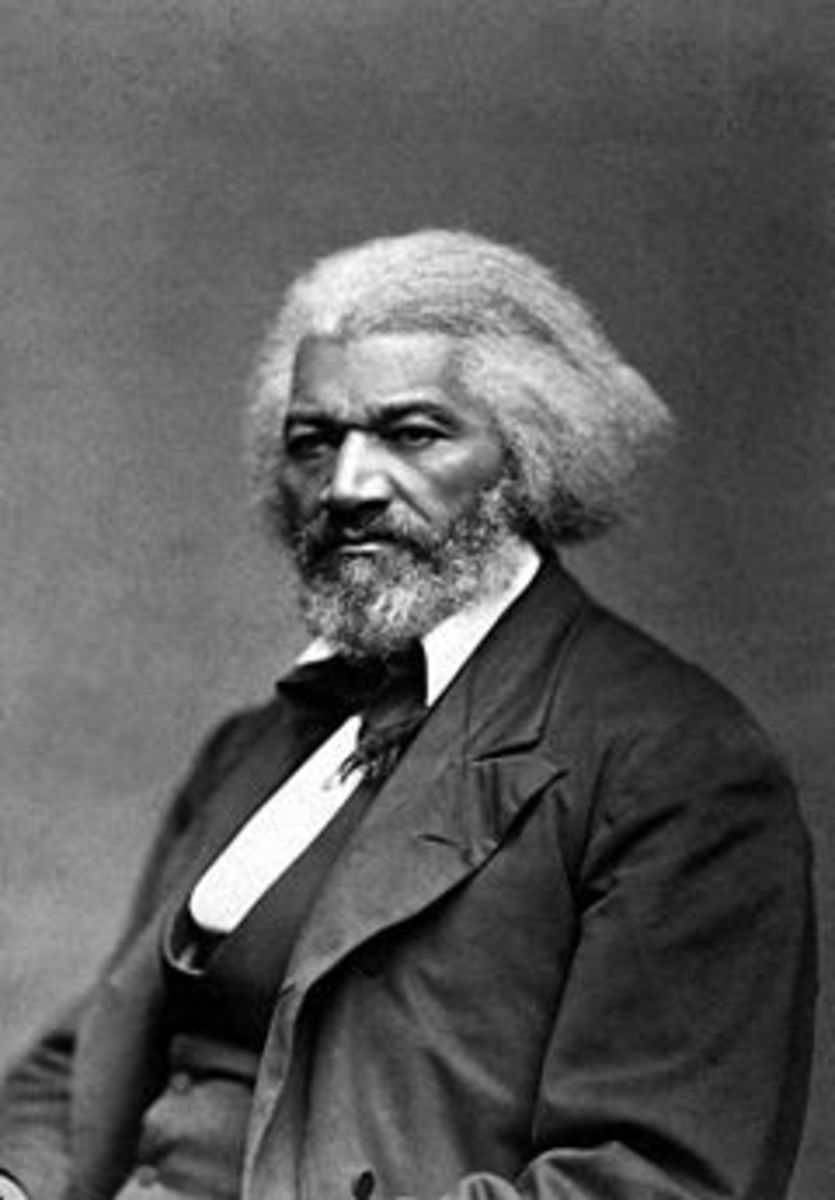

![Although black soldiers fought for their country, they were not U.S. citizens. Frederick Douglass said that by bearing arms 'no one can deny that [they have] earned the right to citizenship.' Although black soldiers fought for their country, they were not U.S. citizens. Frederick Douglass said that by bearing arms 'no one can deny that [they have] earned the right to citizenship.'](https://usercontent1.hubstatic.com/7751506.jpg)

Background

When the Civil War began few whites, in the North as much as in the South, thought it appropriate or even safe to permit African-Americans to enlist as soldiers. Things changed however, with the Emancipation Proclamation which allowed for the formation of regiments consisting solely of black troops. For President Abraham Lincoln though, enlisting black soldiers was a practical measure to assist in preserving the Union, but he feared repercussions from the Border States, where the idea of arming black men was repugnant to most white citizens.

After the Confiscation Acts passed by the US Congress in 1862, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and the military governments of Louisiana and South Carolina began forming black regiments. Response to recruitment drives was mixed- in the state of New England free blacks had been turned away when they tried to join up in 1861 and now some thought twice about enlisting. In the occupied South, newly freed slaves flocked to join up; excited by the prospects of steady pay and striking a blow against their former masters.

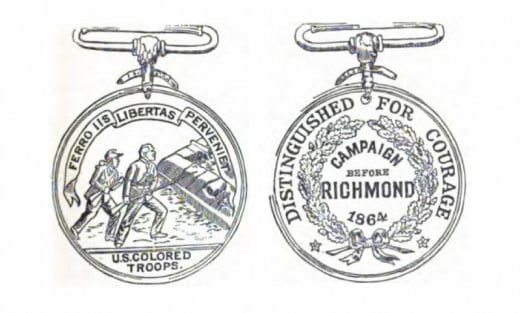

The Butler Medal

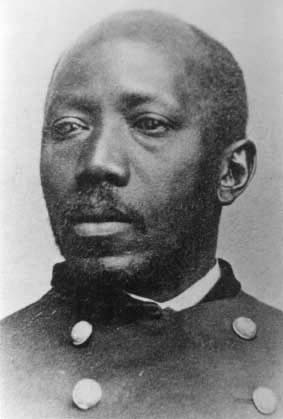

A Decorated Black Union Officer

Major Martin Delany

The first black field-grade officer in the history of the U.S. Army, Delany had been a pre-war abolitionist and was among the first three black men accepted to study medicine at Harvard. During the war he helped recruit thousands for the U.S.C.T. Lincoln was impressed with him when they met in 1865, calling him a 'most extraordinary and intelligent man.' He was commissioned a major two weeks later, the highest rank attained by an African-American during the war.

Additional Hazards

In addition to the usual hazards associated with military life, black soldiers faced other difficulties. Confederates reacted strongly to the prospect of black Union soldiers. President Jefferson Davis issued a proclamation in December 1862 that directed all Confederate military officers in the field to turn over captured black Union soldiers and their white officers to state, rather than Confederate authorities. In this capacity any prisoners could be indicted for insurrection or inciting insurrection and sentenced to death. On the 1st May 1863 the Confederate Congress went one step further and passed a joint resolution authorising Davis to allow such captured white officers to be put to death and to sell black enlisted men back into slavery.

Lincoln’s response to this was stern: for every captured Federal officer put to death, an imprisoned Confederate officer would be summarily executed in the North. There were no recorded cases of white officers being executed by Rebel authorities but there is strong evidence of seized black soldiers being returned to slavery. Moreover, Southern soldiers finding themselves confronted by black Union soldiers often discarded any semblance of obeying the rules of war. Barbarities were not uncommon; the most notorious were those committed at Fort Pillow, a Union garrison on the Tennessee side of the Mississippi River. On the afternoon of the 12th April 1864 Confederate cavalry commanded by Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest ‘shot down, bayoneted, and put to the sword in cold blood,’ hundreds of black soldiers as they tried to surrender. In response to the massacre, black Federal volunteers adopted ‘Remember Fort Pillow,’ as their battle cry and thereafter sometimes engaged in their excesses when dealing with apprehended Confederates.

Whether in a state raised regiment such as the famous 54th Massachusetts or in one of the 166 regiments of the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.), soldiers in a black regiment inverted the two principal Union war goals compared to their white comrades: they fought to free their people first, and preserve the Union second. As Frederick Douglass said, ‘The iron gate of our prison stands half open. One gallant rush from the North will fling it wide open, while four millions of our brothers and sisters shall march out into liberty.’

An Overview Of The African-Americans In The American Civil War

White Attitudes

The first black volunteers were infused with a profound sense of purpose, which steadied them as a series of challenges were flung their way from within their own army. First, many white soldiers disliked the idea of arming blacks, and some flatly refused to serve near them. Theodore Upson of the 100th Illinois wrote that ‘none of our soldiers seem to like the idea of arming the Negroes. Our boys say this is a white man’s war and the Negro has no business in it,’ Recent immigrants to the North took a different tack. As one Irish journalist explained: ‘I’ll let Sambo be murthered instead of meself on any day of the year.’

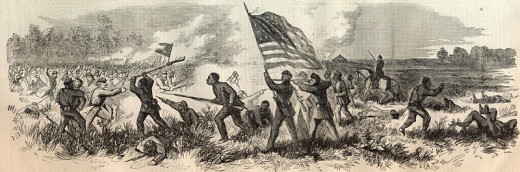

Battle Of Milliken's Bend

Official Discrimination

It took demonstrated bravery on the battlefield for such racial stereotypes and prejudice to subside. By the war’s end, most white Federal troops still viewed their black comrades somewhat askance, but few questioned their value and devotion to the Union cause. However, black troops still had to deal with bureaucratised discrimination.

At first, black privates received $12 a month, the same as white soldiers, but in June 1863, the War Department announced that henceforth they would only receive $10, and be required to pay $3 of that toward a clothing allowance. In June 1864, this cruel disparity was remedied, but lasting damage had been done to black morale.

Never redressed was the apparent unfairness of disallowing black officers, with very rare exceptions. In all the black regiments that served in the war, there were only 32 black officers, and most were chaplains and surgeons. A special school to train officer candidates for black regiments opened in Philadelphia in late 1863, but its only graduates were white.

Routine Work

Black regiments were often detailed to mundane second line duties, such as digging trenches, clearing trees, guarding railroads, and protecting communication lines. Even after black valour was proven by the assault on Port Hudson on the 27th May 1863, where the bravery of black regiments first came to the Northern public’s attention, troops rarely saw action proportional to their numbers in the Union armies.

When black units were called on to fight in a decisive action, such as at the Battle of the Crater, it was often under adverse conditions that made high casualty rates likely. This fact disgruntled many people in the ranks, leading to recruitment difficulties later. Even so, African-Americans made up 12 per cent of Union soldiers by the end of the war.

Exploring The Courage Of African-American Soldiers

Two Highly Recommended Links

- afroamcivilwar.org

The official website of the African-American Civil War Memorial and Museum. - African Americans and the Civil War - African Americans and the Civil War - LibGuides at Rhode Islan

A website dedicated to the commemoration of African-Americans that fought for both sides in the American Civil War.

Final Glory And Final Insult

Despite their impressive combat record, discrimination against black soldiers continued through 1865, and beyond in the post-war US Army. One particularly defining example of this, involved the Union’s 25th Corps which was almost completely composed of black regiments and even had the honour of being the first to enter the Richmond when the Confederate capital in April 1865. The next month though, as the two Union armies marched in triumph in the Grand Review in Washington, not a single black unit was among them.

By the end of the war, 186,000 black soldiers, with 119,000 of them former slaves had fought for the Union. Black troops earned 21 Medals of Honour and had suffered 68,000 casualties, an astonishing rate of loss.