- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

American Environmental Perspectives and the Role of A Sand County Almanac

A Few Leaders of the Environmental Movement

Leading Environmental Perspectives

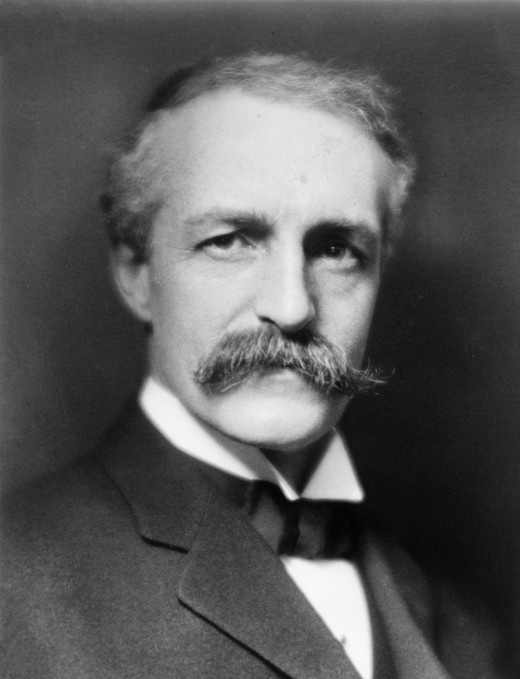

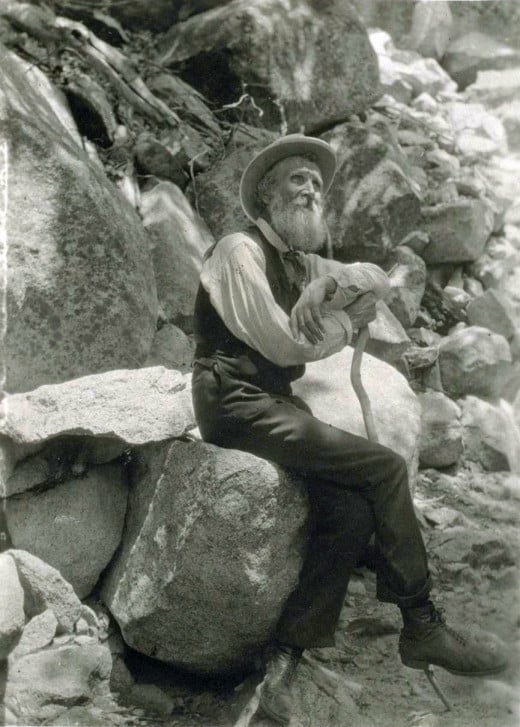

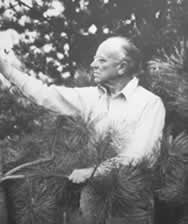

Views on the environment have changed immensely over time. Each view has been professed by a different person. One of the first organized ideas about the environment came from the romanticism movement. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau both enlightened the people about the beauty of nature through their writing. Later, two ideas developed regarding nature's place in the human world. The first, the conservation movement, whose forerunner was Gifford Pinchot, professed the greatest good for the greatest number for the greatest amount of time. This ideology was adopted by the United States government in their attempts towards environmentalism. Shortly after, a preservationist movement sprung up. One of the forefathers of the preservationists was John Muir. Muir believed that nature should be set aside and enjoyed for itself. He believed that nature had a spiritual aspect to it that should not be ignored. Aldo Leopold, like Muir questioned what progress really is. In his book, A Sand County Almanac, he outlines the traditional sense of progress and the improvement of land. He also shows disparities within the conservationist movement and the possible loss due to such “progress”. Through personification, he shows the reader that nature is something humanistic so that we can realize how close we actually are to what we are leaving behind. He also presents a new idea of what progress actually is.

What is Progress?

Traditional ideas of progress have typically come from the conservation movement. The conservation movement believes in improving on the land through development. As part of this development the United States government sponsored many projects like the development of the highway system and dams.[1] In the early twentieth century, the United States built dam after dam. Eventually they even dammed the Colorado River in so many places that at times it runs dry by the time it meets the Mexican-American border. The Colorado River is dammed to provide much needed water to its surrounding areas and hydroelectric power. It is only because of projects like this that the American west can be as densely populated as it is.[2] Conservationists, like Pinchot, convinced the United States government to put aside land in forest reserves to be saved for future use.[3] This is part of the idea of their ideology the greatest amount for the greatest number for the greatest amount of time.

Aldo Leopold responds to conservation by exposing some of the repercussions of progress. He argues that many of the ones pushing for progress do not understand the real effects that they will have on the environment. One example Leopold uses is in his discussion about Illinois and Iowa. He discusses a farmer who has carefully stripped his land for farming. All that remains is a thin strip of sod that the fence lays on.[4] According to Leopold, the farmer cut his field as close to the fence as possible to get the most use out of the land for the greatest crop yield. Leopold imagines the farmer saying, “Waste not, want not” in response to his through use of the land. However, such complete use of the land like this leads to erosion and destroys the ecosystem in which many animals may have lived.[5]

This farmer also did not consider the effects his use of the land would have on the others living within his community. Aldo asserts that because of our sense of ownership of land, we tend to ignore the fact that what we do to the land that is “ours” affects more than just the land owners.[6] This is heightened by the fact that nature does not have any sense of ownership.[7] Conservationists tend to only look towards the economic value of the land, and this seems to be Aldo’s biggest problem with their movement. This is, according to Leopold, because “most members of the land community have no economic value.”[8] There are special cases, but they are only made for charismatic species.[9] Therefore, most of the environment is not even considered in conservation.[10]

[1] "Documentary Chronology of Selected Events in the Development of the American Conservation Movement, 1847-1920." The Library of Congress, 3 May 2002. Web. 21 Apr. 2011. <http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amrvhtml/cnchron6.html>.

[2] Gelt, Joe. "Sharing Colorado River Water: History, Public Policy and the Colorado River Compact." Arizona.edu. The University of Arizona, 2003. Web. 21 Apr. 2011. <http://ag.arizona.edu/azwater/arroyo/101comm.html>.

[3] "Documentary Chronology of Selected Events in the Development of the American Conservation Movement, 1847-1920." The Library of Congress, 3 May 2002. Web. 21 Apr. 2011. <http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amrvhtml/cnchron6.html>.

[4] Aldo Leopold. A Sand County Almanac. (New York: Ballatine Books, 1970). Pp. 127.

[5] Ibid. pp. 127.

[6] Ibid. pp. 245.

[7]Ibid. pp. 37.

[8] Ibid. pp. 246.

[9] Ibid. pp. 247.

[10] Ibid. pp. 246.

Background of Conservation VS Preservation

US Army Corps of Engineers' Dam Along the Fox River in Wisconsin

Contradictions

Leopold also argues that there are contradictory actions within the conservation movement itself that slow its own goals. Many of the ideals of conservation are lost in the bureaucratic stages. He also claims that “we still slip two steps backward for each forward stride” with conservationism.[1] A vivid example of this is in the Wisconsin chapter of his book. Aldo informs us that in 1943 the State Conservation Department bought land along one of the rivers in Wisconsin in order to restore it as a wild area. In their efforts the State Conservation Department blocked unnecessary development in this area. In 1947 locals applied to the legislature for a dam to be built for cheaper electric power. The legislature approved the dam to be built barely considering the side of the Conservation Department and their restoration of that land.[2] Furthermore, the Conservation Department was barred from “any future voice in the disposition of power sites.” In this case one branch of the conservation movement in Wisconsin undermined the efforts of the other, and in the end of the account, what seems to most deeply sadden Leopold is that future generations may not even know what they will be missing in the future because of actions like this.[3]

[1] Ibid. pp. 243.

[2] Ibid. pp. 123.

[3] Ibid. pp. 124.

The Community Concept

Aldo asserts that humans need to think of the environment in terms of a community that includes us as humans. He outlines what he calls “the community concept” as the idea that, “the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts” and that “his instincts prompt him to compete for his place in the community, but his ethics prompt him also to co-operate.”This is where Leopold brings in his concept of “Land Ethic”. His ideology is that the inclusion of “land ethic” broadens what we consider our community to include “soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.”[1] Once we combine these two concepts together, we will be able to respect the land.[2]

Aldo personifies the environment to connect it to the reader’s sense of their community. He appeals to our desire to create and our sense of beauty when he ascertains that the river is a painter. Comparing the river to artists, he gives the river a temperamental personality.[3] He begins with this closed in scope of the humanistic river, and then on the very next page, he broadens it to show the river acting as part of its community and co-operating with its other members.[4] In the case of the Silphium, Leopold refers to the extinction of the plant as “one little episode in the funeral of the native flora.”[5] He uses this term usually reserved for humans to not only give respect to the gravity of the situation, but also to evoke the reader to lament this loss as he does.

A Sand County Almanac is often indignant about the lack of general knowledge Aldo assumes the average person to have about the environment. Leopold laments about the forgotten species that exist among us. In the case of the Silphium, he says “we grieve only for what we know.” There is “no cause for grief if one knows it only as a name in a botany book.”[6] This quote expresses his wish that people would educate themselves more in the natural world so that they have a better understanding of what the loss of part of the environment actually means. In another section, he talks about an abandoned farm; indifferently he mentions the failure of the farm and the evection of the family who lived there. He focuses on the fact that the land won out, stating that it was not meant to be used for growing corn anyway. The land has begun to take back the farm.[7]

[1] Ibid. pp. 239.

[2] Ibid. pp. 240.

[3] Ibid. pp. 54.

[4] Ibid. pp. 55.

[5] Ibid. pp. 50.

[6] Ibid. pp. 51.

[7] Ibid. pp. 61.

Aldo Leopold's Shack

Conclusions

In conclusion, Aldo Leopold’s book, A Sand County Almanac, moves past the ideas of conservation. He argues that conservation is flawed because it does not look at the majority of nature. Leopold is perceived more closely along the lines of preservation. However, he presents a new form of preservation, believing that nature is not merely a spiritual place outside of the real world that one visits. He believes that humans are part of a broad community that includes nature. In A Sand County Almanac, he personifies nature to help build that connection with the reader. Aldo Leopold’s ideas helped shape the environmental movement since the first publication of his book.