- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

Another Look at the Interaction of American GI's and German Soldiers During W W II

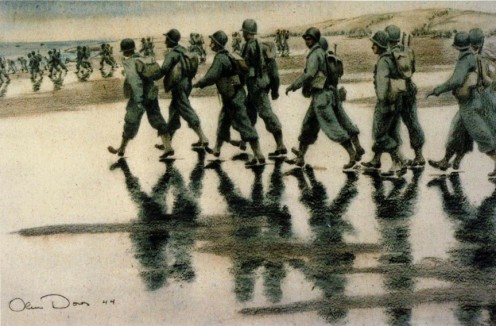

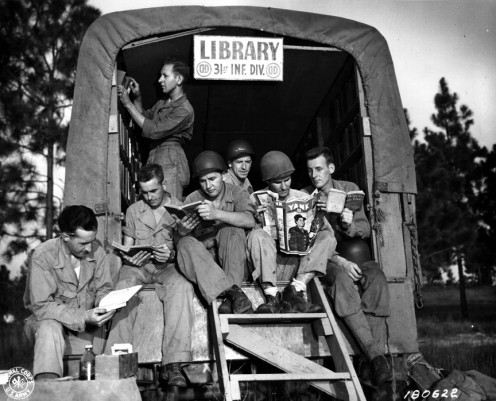

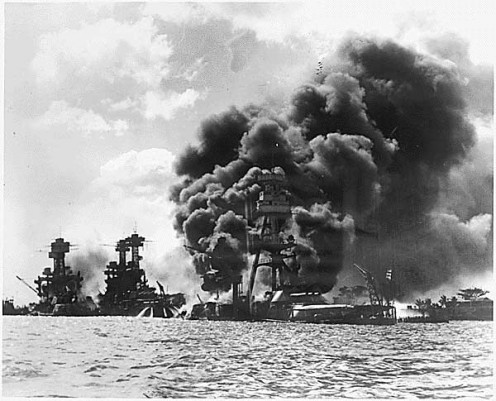

American Soldiers in World War II

American GI's Engage German Soldiers on German Soil

Undeniably most GIs were horrified and morally outraged by their experience in the concentration camps, however, moral outrage did not always lead to retaliation and abuse of German soldiers. Some GIs stressed the importance of the Geneva Convention, the rules for treatment of captured or surrendered enemy soldiers, and indicate that the tenets of the Geneva Convention were upheld.[i]

Lieutenant Smith noted that, "the standing order for any prisoner after he is disarmed--the Geneva Convention--he is protected--[it is] a standing order not to allow violence against anyone." According to Lt. Colonel Moncrief "there were no orders issued to treat the German guards any different than any other German soldier."

Sergeant Adzick had standing orders to protect German POWs as they were needed for interrogation purposes to improve local American intelligence efforts. Infantryman Mills had no knowledge of American GIs shooting unarmed German soldiers and observed that such an action, would be deemed an atrocity. Alexander Breuer was ordered by his Commanding Officer to shoot German soldiers attempting to surrender, but refused his CO's command as it conflicted with the Geneva Convention.[ii]

Some GIs recall an occasional incident where German soldiers attempting to surrender were fired upon, but claim that for the most part captured enemy soldiers were treated well.[iii] When asked how American soldiers handled German prisoners, Howard Lewis replied that "in general [they were treated] very well. But with one angry guard and one prisoner in the middle of the forest our treatment sometimes got out of hand." Mr. Lewis remains convinced that this was a rare occurrence.[iv]

Other servicemen noted that captured German military were much more likely to be shot near or just behind front lines. Captives who made it to rear areas were usually protected and treated decently. PFC Reagler testified that "he did not doubt that some prisoners were shot by front line troops," but his experience was that prisoners who made it back to a POW cage or holding area had little to fear.[v]

The rage and revulsion occasioned by the scenes inside the concentration camps prompted a substantial number of American soldiers to temporarily disregard the Geneva Convention regulations concerning surrendered enemy personnel. Two GIs specifically recall a verbal order from a superior to "take no prisoners."[vi]

George Pisik who participated in the liberation of Dachau described how his superior officer made his wishes known to the troops. The Commanding Officer would select Pisik and another GI and assign them the task of transporting German prisoners back to holding cages or POW enclosures, which happened to be ten miles or more to the rear.

They would then be carefully instructed to "take your firearms with you and be back here in twenty minutes." As this feat was physically impossible, Pisik and the other GIs understood their superior's meaning. They were expected to, and in fact usually did, fall back briefly, shoot the prisoners, then, quickly catch up with the main body of troops which had continued moving forward.[vii]

Although receiving a specific command to take no prisoners from one's CO seemed to have been fairly uncommon, what was common, according to the testimony of numerous GIs, was a low-key passing of the word, from soldier to soldier, to take no prisoners.

American GIs tacitly agreed to shoot enemy soldiers whom they held responsible for the camps and atrocities without specific orders from their superiors.[viii] Lieutenant Gibson who entered Ohrdruf concentration camp described the situation he encountered. "During the following two weeks it was extremely difficult to acquire prisoners since our men killed most of the Krauts that made an attempt to surrender. We required prisoners to learn intelligence so that our future operations would be more successful [and have] fewer casualties.

I had one hell of a time convincing my men of this."[ix] Major King, who spent time at Mauthausen concentration camp, described the prevailing atmosphere among his men. "Troops do run in moods. And it would be very dangerous to be a German soldier in that area in that camp...your life expectancy would be quite low...the troops were in no mood for taking prisoners or anything of that sort."[x]

What is striking about the testimony of some GIs is their careful attribution of American atrocities to "other" platoons and "other" companies, followed by the assertion that the men in their own platoons and companies did not commit such acts. Having made such comments in a slightly conspiratorial manner, a few GIs mentioned their apprehension that war reputations be protected and honored and after-the-fact military investigations not be initiated

Off the record, one service man informed me that his fellow veterans were genuinely fearful of an investigation, even as late as the 1980s and 1990s. This fear was based in measure upon the fact that a formal Inspector General Investigation was launched in May 1945, and there was an initial recommendation that a number of soldiers be brought up on charges before a court martial.

There is one incident where American troops shot unarmed German soldiers that is extensively and officially documented; it took place in Dachau concentration camp on the day it was liberated. This incident was rarely spoken of or written about publicly for many years, although it is now apparent that military personnel at several levels in the army chain of command had knowledge of the incident.

In 1986 Colonel Howard Beuchner published a book detailing, in a rather emotional and commemorative tone, the events which transpired in the Dachau compound on April 29th.[xi] However, Beuchner's book alone was not sufficient to verify the alleged Dachau shooting.

To Be Continued

[i]. Captain Carlisle Woelfer, p. 6, Emory; Corporal Phillip Trout, PFC James Johns, Sergeant Donald Johnson, p. 2, PFC Olvis Day, p. 4, PFC Fred Peterson, p. 3, Q-Ast; Captain Melvin Rappaport, letter to Theresa Ast, December 1993.

[ii]. 1st Lieutenant Conrad Smith, pp. 4, 6, Lt. Colonel James Moncrief, p. 6, Sergeant George Adzick, p. 3, Q-Ast; Mills in Strong, Liberation of KZ Dachau; Alexander Breuer, videotape interview, Record Group 50, International Liberator's Conference, October 1981, Washington, DC. (hereafter cited as ILC).

[iii]. Charles Roland (99th Infantry Division), PFC Max Norris (99th Infantry Division), Staff Sergeant Robert Burrous (80th Infantry Division), Staff Sergeant Michael Gracenin (99th Infantry Division), Tech Sergeant Jacob Hayes (99th Infantry Division), Survey, MHI.

[iv]. Howard Lewis (99th Infantry Division), Survey, MHI.

[v]. 2nd Lieutenant Richard Byers (99th Infantry Division), PFC Leroy Sprague (89th Infantry Division), PFC Charles Kissel (89th Infantry Division), PFG David Reagler (99th Infantry Division), Survey, MHI.

[vi]. Tech Sergeant John Sushereba (80th Infantry Division), Staff Sergeant Curtis Whiteway (99th Infantry Division), Survey, MHI.

[vii]. George Pisik, interview with Theresa Ast, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, July 1993; 2nd Lieutenant Ray Millek, Sergeant Bob Brennan, Private Martin Drus, Private Jim McCarthy, (all in the 103rd Infantry Division), in Richard M. Stannard, Infantry: An Oral History of a World War II Infantry Battalion, (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1993), pp. 253, 255-256, (hereafter cited as Stannard, Infantry).

[viii]. Colonel Howard Beuchner, Chaplain Leyland Loy, John Lee, Felix Sparks in Strong, Liberation of KZ Dachau; Dr. David Ichelson, manuscript, "I Was There," p. 153; Major Douglas Monsson, Staff Sergeant Monroe Nachman, HMFI; Walter McCloskey, ILC; Sergeant Loren Hollister, p. 2, PFC Olvis Day, p. 2, Captain/Chaplain John MacDonald, p. 2, Captain Edward Gossett, p. 1, Q-Ast; 2nd Lieutenant Charles Brousseau, DMC; 2nd Lieutenant Frank Hamburger, p. 4, Major M. Montesinos, p. 9, Emory; PFC Marion Sinelli (97th INfantry Division), Survey, MHI.

[ix]. 2nd Lieutenant Samuel Gibson, p. 2, Q-Ast.

[x]. Major George King, p. 4, Emory.

[xi]. Colonel Howard Beuchner, Dachau: The Hour of the Avenger, (Metairie, Louisiana: Thunderbird Press, Inc., 1986).

Histoical Articles that Might be of Interest

- What Most Germans Knew About the Nazi Concentration ...

In their oral history testimonies, letters, questionnaires, interviews, and journals American soldiers explain why they did not accept German protestations of ignorance and innocence. GIs from the 42nd, 45th, 71st, 88th, and 103rd Infantry Divisions, - Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon married firstly, Arthur Prince of Wales who died before the marriage was consumated. Her second marriage was to Henry V111TH but as soon as she failed to produce a son, the King took drastic action to extract himself from the marr - American GI's and German Soldiers

Considering that America was engaged in a war against Germany, American soldiers, with few exceptions, entertained fairly positive, even sympathetic feelings for German soldiers and civilians. After the war veterans were asked to name their favorite - Early Saxon England- the growth of the heptarchy

Discover who occupied Britain after the Romans left, and find out about the seven kindgoms of England - Czechoslovakia Under Soviet Rule: Personalizing Hist...

Heda Margolius Kovaly, living in Eastern Europe, survived the Nazi regime in the 1940s and the the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia during the 1950s and 1960s. Sadly, her husband and many of her friend fell victim to Stalin's terror.