- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War Life: The Union’s Path To War - Those Who Volunteered

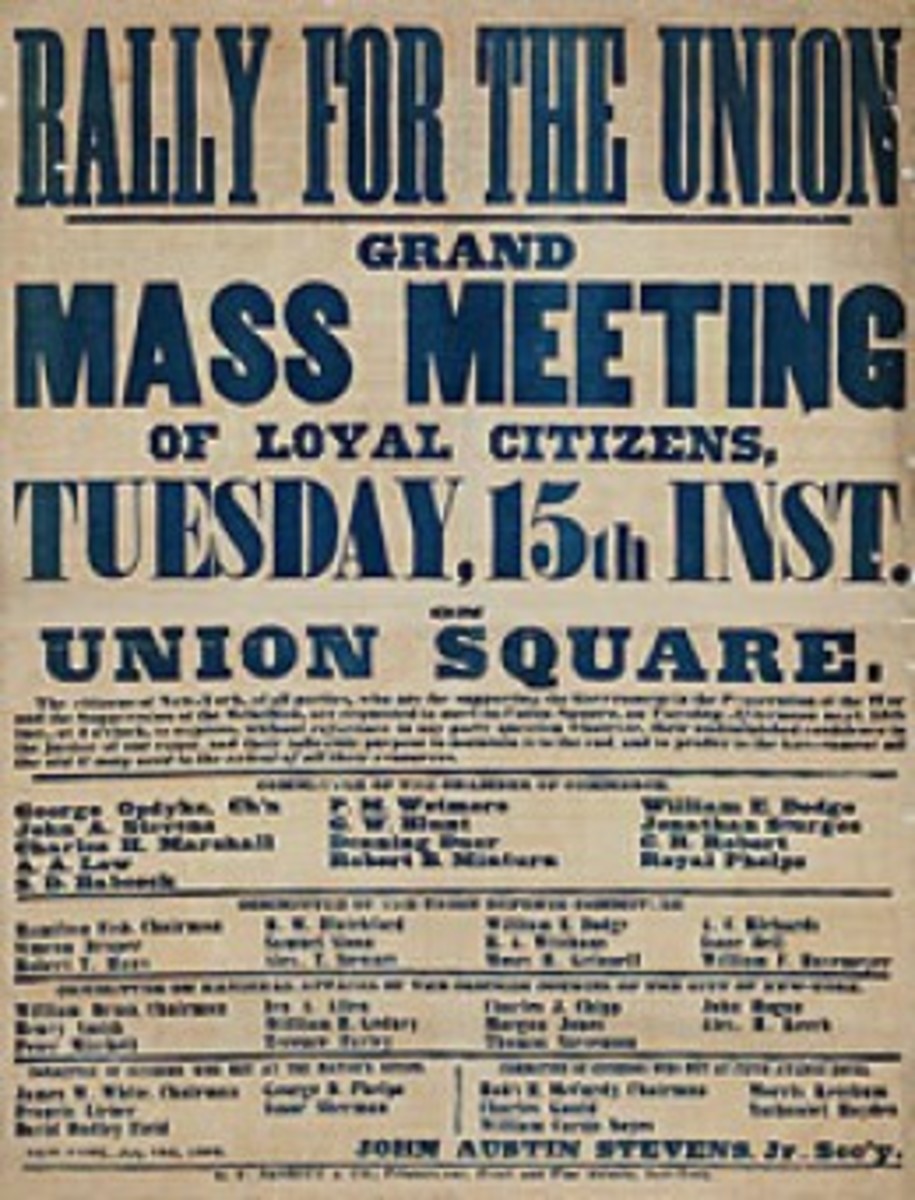

Rallying behind the Union, and its government, and condemning the bombardment of Fort Sumter was all well and fine. However, risking one’s life in volunteering to go to war was quite a leap forward.

Why, then, did Union men do so, and in such sizeable numbers?

The Reasons To Volunteer

The average Union man was very patriotic, toward his community, his state, and his country. He may not have known if he was a Democrat or Republican, but he believed in the Union first and foremost, and its democratically elected government of the people.

As mentioned before, Union men looked upon the Confederate cannons’ bombardment of Fort Sumter as an insult to flag and country.

The Union’s vision was clear: the offending side needed to be subjugated to the authority of the lawfully elected U.S. Government and punished. The North was not about to see its republic torn apart without a fight. The thousands of recent immigrants from Europe were especially vehement in the desire to fight for their new, democratic country, and to keep the nation whole. About one in five who fought for the Union was foreign-born.

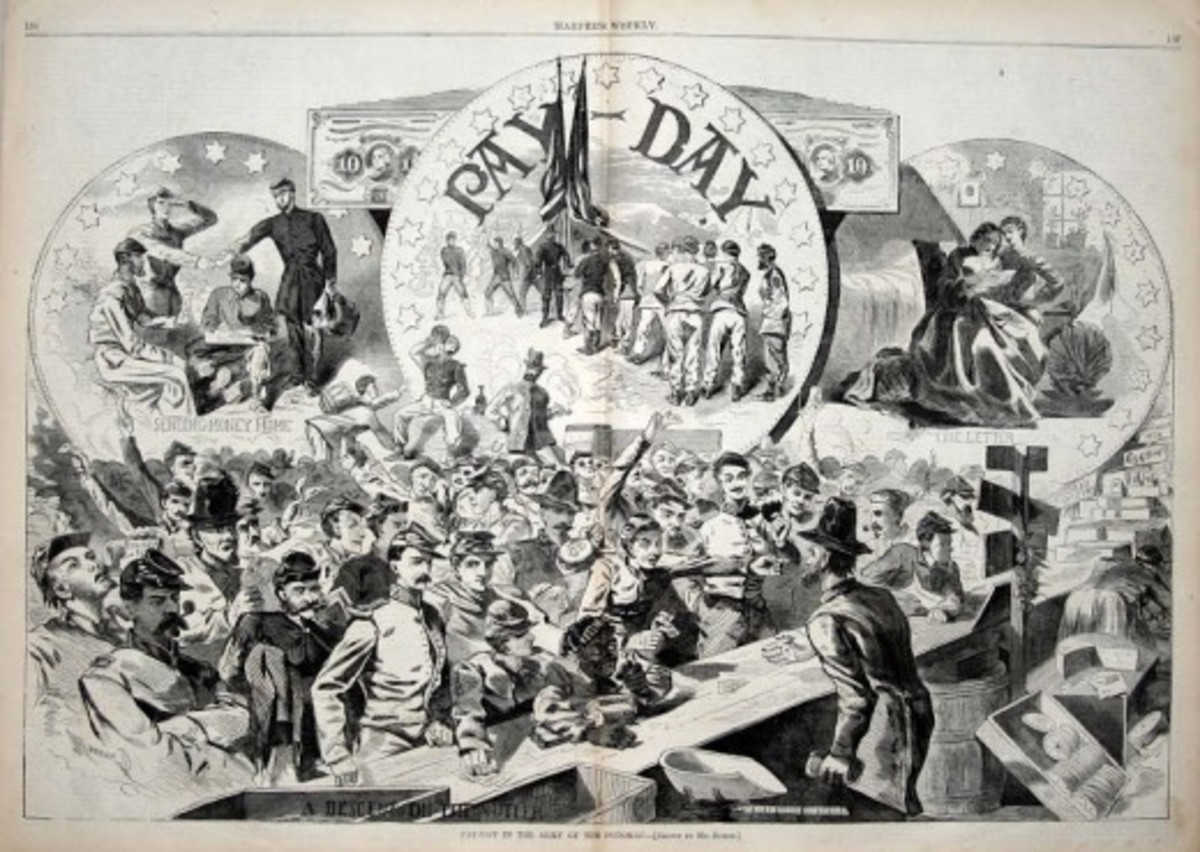

There were certainly motives other than patriotism for pro-Union men to enlist: chances for travel and adventure were an inducement for those men who rarely ventured outside their own farms much less beyond their own towns. The desire for money via soldier’s wage and/or looting was a major inducement as the North, at the time, was suffering from widespread unemployment. However, in the end, by and large, patriotism was the major reason why thousands of American men enlisted in the United States military and put their lives at risk for their country.

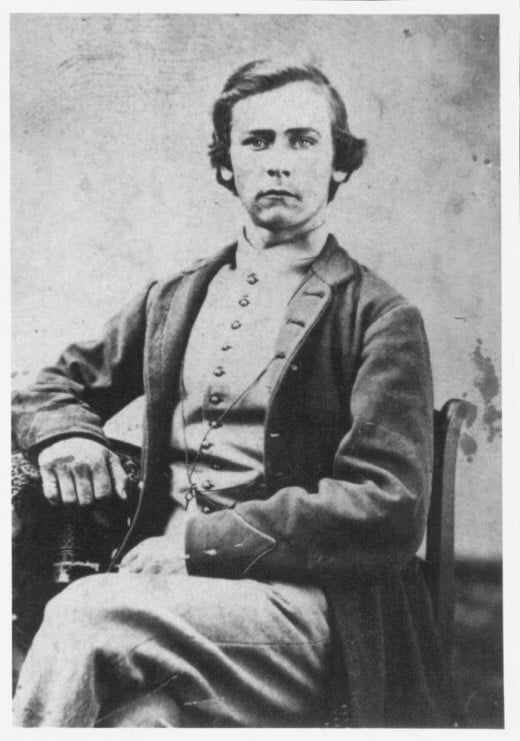

The Men

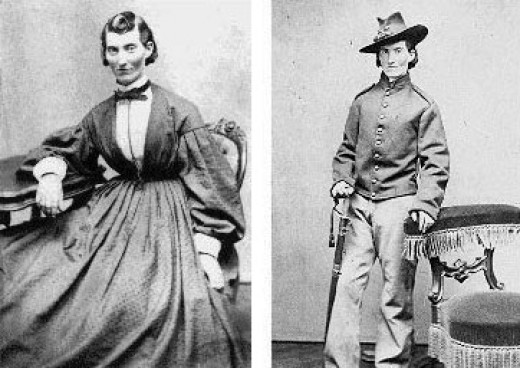

The man that became a United States soldier in the mid-19th century was, on average, a man not too much different from a man today, though not as prone to obesity. He averaged 25 or 26 years of age, between 5’8” and 5’9” (~1.73 m and 1.75 m) in height, and 143 pounds (~64.86 kg) in weight. By medical standards of the day, his health was generally good at the time of enlistment. However, it should be mentioned, due to the need for large numbers of troops, medical inspections were often indifferent and/or inexpert. Many men suffering from physical or mental diseases or injuries were able to enlist. These medical inspections, or lack thereof, also allowed many women, disguised as men, to enlist. Approximately 1,000 women, on both sides, enlisted and fought as soldiers during the war, most doing so with the full knowledge and cooperation of men. Many were wives following their husbands into the army, as later evidenced by a significant number of pregnancies and births among the troops during the course of the war!

Their Occupations

Nearly half of all Union soldiers had the occupation of Farmer, out of a total of 300 occupations. Factory workers, machinists, office clerks etc, were some of the other occupations that were pursued by the troops in peacetime. A man’s occupation was often dependent on where he lived. If he lived in rural surroundings, chances are he was a farmer. If he lived within urban surroundings, he was more likely a factory laborer or clerk rather than a farmer.

How They Subsisted

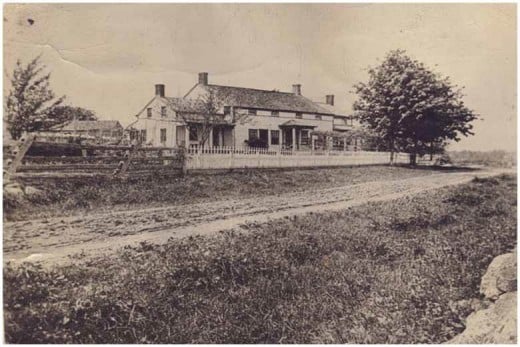

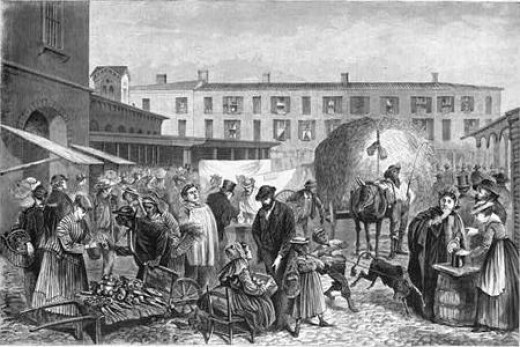

Americans living in the more rural parts of the country often pursued at least some sort of subsistence farming, from which to feed and clothe themselves, if not commercial farming as a business. Those not owning commercial farms often worked for those who did. The output, from these commercial farms, was then taken and sold to the markets in the nearest towns and cities. For goods and supplies they did not make themselves, farmers visited these same markets.

Americans living in the more urban parts of the country had more access to these markets wherein they got their supplies and sustenance. Shopping in these markets was similar to shopping at specialty counters in supermarkets today. Shoppers at the market told the clerks what they needed, and the clerks retrieved those items for them. Depending on the market, those items ranged from fruits and vegetables, to seeds and grains, to firearms and ammunition.

Their Educations

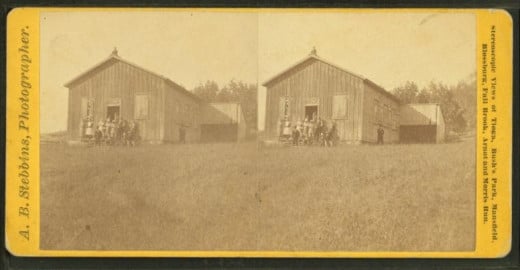

Most men had remedial educations, which included reading, writing, spelling and grammar, history and geography, arithmetic, Latin, and music. The school itself was most likely a small, one-room building with a single teacher, who cleaned the interior and stockpiled firewood among his / her duties. Though the new practice of grouping grades by age was taking hold throughout the country, the odds were somewhat good that the schoolroom contained students of various ages and/or school grades.

The expected term of education of most children was from age 6 through age 14, and when school was in session, the day generally lasted from about 9:00 am to about 3:00 pm (0900 to 1500), give or take an hour, from Monday through Friday. Reading was heavily emphasized, so much so that a student, aged 11 years, was reading at or near today’s U.S. collegiate level. There was no scoring of the schoolwork. However, the students were tested, mostly orally, through recitations of the lessons with the teacher, either one-on-one or with other students in his grade.

Corporal punishment, such as beatings (with a belt or other strap) for those students that misbehaved, was common and even encouraged by the parents.

Due to the agricultural character of much of the country, students were off from school during harvesting time (summers) so they could help their families bring in the crops. This is a tradition that continues to this day.

The students graduated upon completing all of their courses through their schooling term. They then received certificates of completion, a forerunner of today’s diplomas, upon graduation.

As a result of this general education, the average man was able to read and write, though at various levels of proficiency. This is evidenced by letters written by the troops during the war!

Going on to college or military academy was generally for the sons of the wealthier class. Most men raised on the farm generally stayed on the farm after their general educations were completed, and the others went on to the factories or the mines or other labor-related careers.

From everyday life in the rural areas, an average man was also knowledgeable in those skills he needed in order to provide for himself and his family. These included such skills as how to work a horse-drawn plow or use a hoe, how to milk a cow, how to build an animal enclosure, how to build a split-rail fence or a stone wall. In general, if a man needed it, he often needed to make it himself. As for living in more urban surroundings, a man still needed to do many things on his own. However, for those tasks needing a greater degree of specialization, he often found proprietorships of such skilled workers within his town or city, after some searching and/or word-of-mouth referrals.

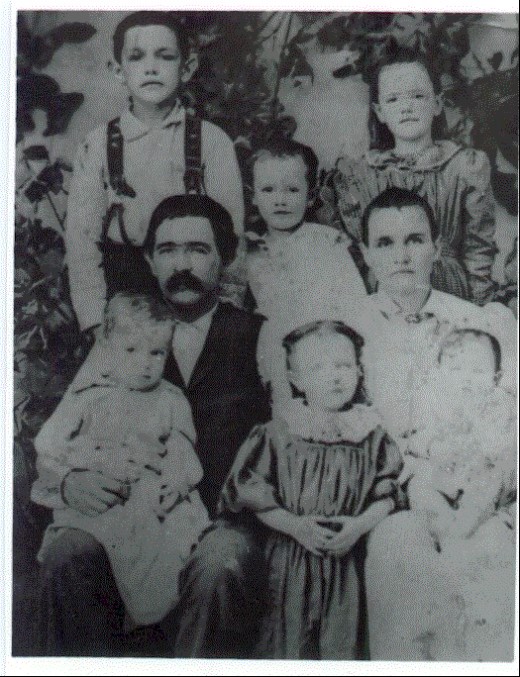

Their Families

While there was a tendency in those day for first marriages to occur somewhat early in life (late teens, early twenties), circumstances dictated the actual marriage scenarios, just like they do today. Similarly, personal circumstances dictated when, or if, couples started their first families.

Families, especially those living in rural areas, were usually bigger than they are today. The thought was that more children meant more hands to work the farm, despite the greater consumption of those very products in which they were born to assist nurturing! It was not unusual at all to have families of five or more children, possibly along with grandparents and other extended family members living under the same roof. Urban families tended to be fairly large as well, though with such finite living spaces as were available, family sizes were often dictated by living space.

Their Mindsets

With a majority of each day spent tending to crops or livestock, or maintaining equipment, or laboring in the workshops or mines, the average man didn’t have a lot of time to devote to non-work activities. However, he made the time to inform himself of the goings-on. He read nearly whatever he could acquire, however far between may have been the arrival of the material. In the 19th Century, the idols of America were politicians and military heroes – those who truly molded the country in which they all lived. Common men listened with great interest to speeches from local or visiting politicians and community leaders at town meetings, or they read reprinted speeches in local periodicals. Given how far apart most people lived from each other in the rural parts of the country, news updates were often quite irregular. However, when the updates came, there was no shortage of men wanting to read them. In cases of hearing the news in public settings, there was also no shortage of those wanting to voice their opinions on what they just heard!

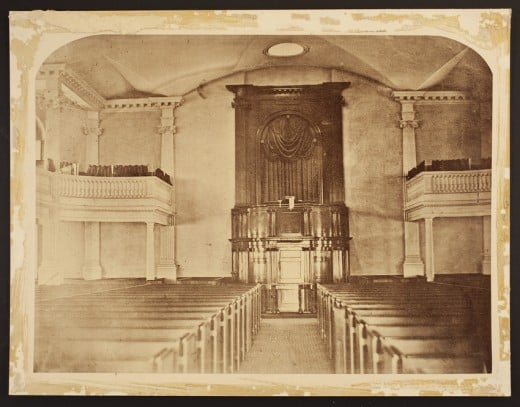

The average American-born man was Christian and deeply religious. He believed in God and sought His Blessing in everything from health, for him and his family, to bountiful crops and good weather, to returning safely from the workday. He was an avid churchgoer and probably kept a copy of the Bible at home from which to read to his family or for his own private reading. Many of the immigrants, especially the Western European immigrants, were a bit more secular. They had experienced, perhaps, too much of the church as a ubiquitous and dominant institution in their daily lives due to little or no separation of church and state in their home countries. They looked upon Americans, with their spiritual customs and habits, as being a bit too religious.

The average northern man’s thoughts on slavery were unfavorable. This was probably due to the fact that slave labor was competition for him in the workplace (as explained earlier). Slavery was also a different institution, and the slaves were a different kind of people, than to which he was accustomed. He may have recognized that slaves were people and that people in bondage was a revolting thought, but his thoughts toward black people probably ended there. They were thought of as inferior, after all, and thus suited for slavery.

The average American man’s thoughts were simple: let my neighbors and me live free and provide for our families, and don’t intrude upon our freedom with peculiar institutions or laws.

In thinking of America, I sometimes find myself admiring her bright blue sky-her grand old woods-her fertile fields-her beautiful rivers-her mighty lakes and star-crowned mountains. But my rapture is soon checked when I remember that all is cursed with the infernal spirit of slave-holding and wrong; When I remember that with the waters of her noblest rivers, the tears of my brethren are borne to the ocean, disregarded and forgotten; That her most fertile fields drink daily of the warm blood of my outraged sisters, I am filled with unutterable loathing.

- Frederick Douglass

Afterword

This ends my first American Civil War Life series, The Union's Path To War.

I will now continue with another series in the realm of American Civil War Life. This next series is called American Civil War Life: Filling The Ranks.

© 2013 Gary Tameling