- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

Andrew Jackson and Those Damn Banks

Good Politics is not Always Good Policy

When I was a kid, I thought that banks functioned essentially like a piggy bank. To keep your money safe, you stick it in a bank where it would be locked and tucked away until you wanted to pick it up. So if you asked me how a bank could possibly make money by just holding on to other people's money, I would be at a loss. Even the concept of checking accounts was a mystery to me.

The piggy bank analogy, of course, does not really work. Most of the money supposedly deposited at a bank is not actually there. The bank, rather than keeping the cash there for safe keeping, takes most of the money and tries to turn it into more money by issuing loans that produce interest and by making various types of investments. So long as a large number of depositors do not show up at the same time asking for their money, it is fine if only a small percentage of the deposits are actually there. Also, so long as the bank does not make too many bad choices in its lending and investing, depositors can be secure in knowing that their hard-earned money will never just disappear.

I suspect that many adults are also confused by what it is exactly that banks do. They just know that banks can sometimes be annoying. When banks lend money, they have the audacity to expect it to be paid back (with all that interest). They also seem to come up with creative ways of charging hidden fees and slowly bleeding their customers dry. Still, on some level, we know that banks are necessary. We need them to issue us credit cards, provide checking accounts so that we don't have to pay cash all of the time, and make it possible for people to make major purchases like houses and cars that they otherwise could not possibly afford. Banks largely make possible a modern world in which the overwhelming majority of purchases that people make are both electronic and made (to some degree) with borrowed money.

Today, we take it for granted that banks are an integral part of our lives. In the early 19th century, however, many people were still getting used to the concept of banks. The majority of people were still farmers, producing on their own many of the things that they consumed on a daily basis. Others were craftsmen or professionals running or working for small businesses that didn't necessarily need the large loans or some of the other financial services a bank could provide. Many people at the time still saw a direct correlation between the goods or services they produced and whatever income they were able to generate. People felt that they produced tangible things through their hard work. Bankers, on the other hand, did not seem to produce anything. Using techniques few people fully understood, they just turned money into more money. It's no wonder that the average citizen was prone to believe that there were nefarious conspiracies being carried out behind the scenes, particularly when financial downturns took place that seemed to have something to do with the foolish (or maybe devious) behavior of bankers.

The biggest, "baddest" bank of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was the Bank of the United States. It was originally established largely through the efforts of Alexander Hamilton shortly after the country began, and after a five year hiatus, was reestablished in 1816. In addition to functioning like a regular bank in which individuals could establish accounts and receive loans, the Bank of the United States had a very large customer called the federal government. The federal government, in addition to being the largest stockholder in the bank, also deposited its money there. So whenever people throughout the country paid government fees or taxes using checks or bank notes from small local banks, these forms of payment would end up at the Bank of the United States. Eventually, officials of the Bank of the United States would then go to these local banks and turn in these pieces of paper for real currency. (Bank notes, by the way, were the closest thing to paper currency at the time. In theory, a bank note could be cashed in to the bank who issued it for the only official currency: metal coins. So these bank notes would often circulate as if they were cash. This therefore gave the banks the ability to put significantly more "cash" into circulation than there were coins in existence.)

Smaller local banks, therefore, often found themselves in the position of paying up to the Bank of the United States, and they knew that they had to keep enough real currency on hand to make good on those checks and bank notes. This put some restriction on how much they were able to lend and how much paper "currency" they were able to create, with many bankers believing that they and the economy in general were being held back by the biggest "baddest" bank in the land.

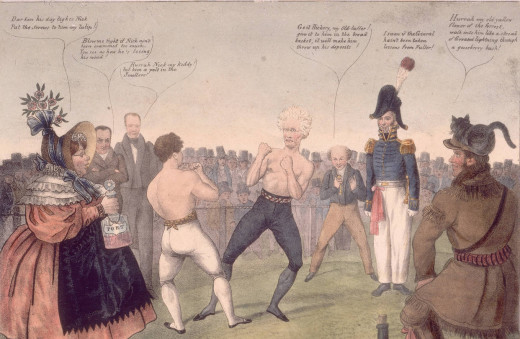

In 1828, Andrew Jackson was elected President of the United States, running as a common man who would represent the average American. He also viewed himself as a man continuing in the tradition of Thomas Jefferson, a man who believed in traditional agrarian America. So like many of the traditional farmers who saw him as their hero, he was not a big fan of banks. He believed that people should only go into debt as a last resort, and he celebrated the people who made real tangible goods with their hands. Needless to say, the Bank of the United States, given its enormous size as the country's only national bank and the general hostility of Jackson's supporters toward banks, was a convenient target that Jackson could go after in order to prove his common man credentials. So when the head of the Bank of the United States and his allies in Congress decided to renew the bank's charter a few years early and keep it going for another 20 years, Jackson vetoed the bill. He then ordered that the federal government money deposited there be spread out to various smaller banks, and the Bank of the United States would never function in its traditional capacity again. A few years later, this former giant of a bank folded completely.

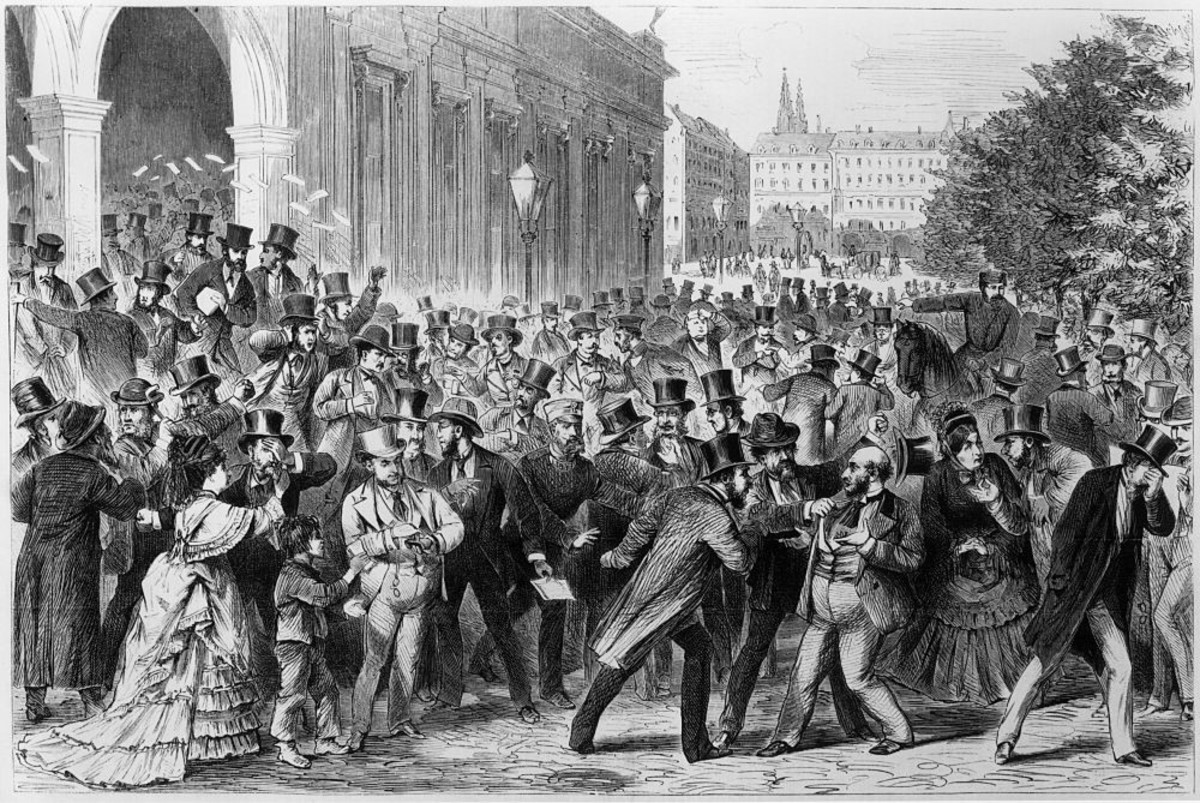

There is little doubt that Jackson scored some political points by taking this action. Many "common men" throughout the country cheered him on as he took down the biggest of the "moneyed interests." The irony, however, is that common people didn't really benefit very much if at all from the results of this so-called "Bank War." Instead, the biggest winners were the bankers and businessmen who wanted the Bank of the United States out of the way so that they could more freely lend money and print bank notes in place of "real" metal currency. Without any institution functioning as a regulator of money lending and the currency, the next 80 years of American history would be a banking free-for-all filled with periodic financial collapses in which banks often played a role in causing the "panics" or making them worse. Unfortunately, common men would often see their money go up in smoke when banks started to fail. Ironically enough, one of these financial panics started in 1837, just a year after Jackson left office. As often happens, the effects of a president's policies were not fully felt until he was gone.

So often, politicians seem to focus on formulating the best political strategies when coming up with ideas and policies to support. They try to come up with the words and the actions that will get them the most votes. Unfortunately, in a complex world filled with many misinformed voters, good politics is often bad policy. Killing the bank may have helped Jackson get reelected in 1832. It probably made him even more of a hero to the "real", average, everyday Americans who voted for him. Unfortunately, the big winners were often the financial speculators who managed to pocket a lot of money and then get out before the next crisis hit. We saw similar scenarios play out in the early 1990s and in 2008 when limited regulation of real estate investments helped lead to huge losses by financial institutions and/or to average Americans losing their jobs and homes. And now, not too long after the latest crisis, the country has turned to Donald Trump, a real estate tycoon and self-proclaimed Andrew Jackson fan. It makes you wonder how many of the common men who voted for President Trump will be sorely disappointed somewhere down the line.