Animals on Trial in Medieval Europe

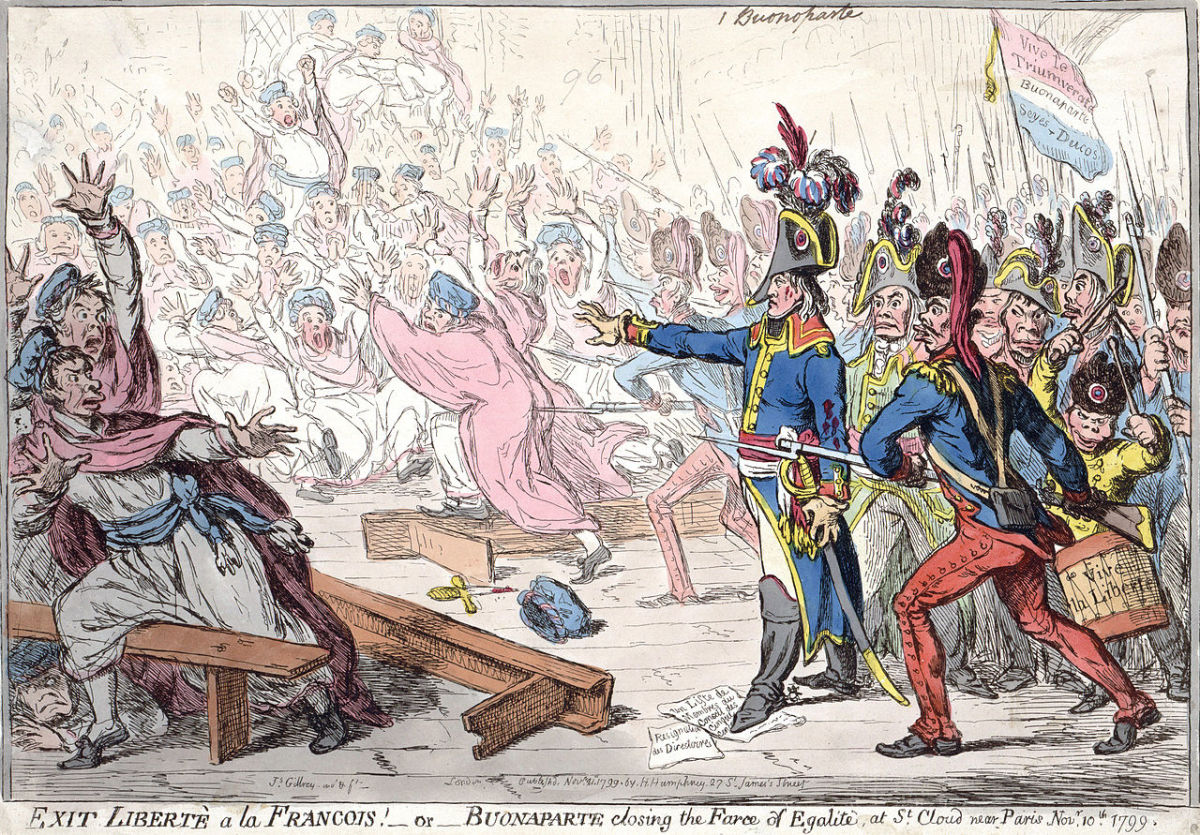

A Landmark Trial

The Court in Provence, France, was hushed. The defendants would have reason to be concerned. The crime with which they were charged carried a sentence of death.

Proceedings opened and they were called to the dock. They were called again. The minutes passed, and it slowly dawned on the assembled legal dignitaries that the accused were not even in the building. They had ignored every Summons that had been sent to them – even a public declaration. This was contempt of Court. The Judge’s face darkened in anger.

Just as things looked as if they couldn’t get any worse, their lawyer stood up to speak. This was when their luck turned. The Defence Lawyer who had been assigned to them was a hot-shot young Attorney by the name of Bartholomé Chassenée. He addressed the Judge confidently, explaining that his clients led an itinerant lifestyle, and as a result may not have even been aware of the Court Summons. The Judge had to agree, adjourning the case until further Summonses could be sent out to the accused.

It wasn't us!

It was a reasonable decision for the Judge to make. The defendants did indeed move around, as they were a gang of rats. It was claimed they had infiltrated the province’s barley stores and "feloniously eaten and wantonly destroyed" the barley.

The trial took place in the early 1500s, when animals were often put on trial as if they were human beings, with the full paraphernalia of the legal process. At the re-scheduled hearing, unsurprisingly, the defendants once again failed to show.

The brilliant Monsieur Chassenée was not cowed. In a lengthy and convoluted legal argument, he contended to the Court that a defendant who could not travel to a place of trial safely should not be forced to attend. His clients risked their very lives coming to Court because of the number of “their mortal enemies” waiting to pounce on them from every corner - that is, cats. The Judge accepted his arguments; all charges were dropped; the rats were left without a stain on their character, and the case made Chassanée’s name.

The Accused Takes the Stand

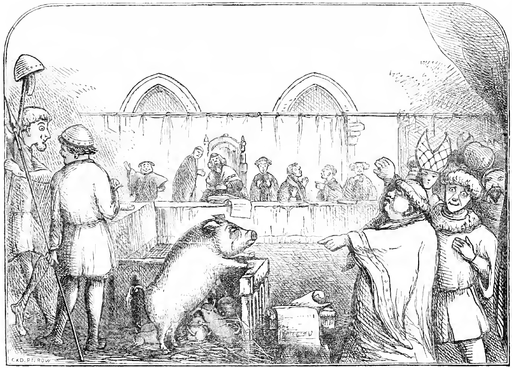

Pigs in Trouble

It was far from being an isolated incident. Across mainland Europe from the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries, animals were put on trial regularly for behaving, well, like animals.

Pigs were the recidivists of the animal kingdom. They were charged with harming children with a frequency that can only have been alarming. In 1386, also in France, a sow and her piglets were accused of murdering a 5-year old child. Eight witnesses took the stand against the mother pig. Finding her guilty, the Judge declared he would "make an example of her" and sentenced her to be hung upside-down by her legs and then burnt. The piglets were acquitted “on account of their tender age and their mother's bad example.”

Was the Law an Ass?

Animal Immorality

Countless female animals were put to death for the crime of bestiality – having sexual relations with a human being. The animal was considered to be just as guilty in this as the human and punishment was ruthless.

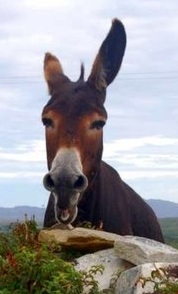

In a rare instance of justice - at least for the animal - a donkey was found not guilty of acts of gross indecency when the local priest gave her a character reference, declaring that he had known her for four years and she was “in word and deed and in all her habits of life a most honest creature.” Whatever the donkey’s “words and deeds” were, it worked and she was acquitted, whilst her owner was hanged.

Sadly, acquittal was rare and most animals were found guilty of all charges against them. This was to be expected, bearing in mind that they could not speak up in their own defence. Often the Judge’s “summing up” of the case before passing sentence would stress the moral turpitude behind the crime and the evil intentions of the guilty animal. Then the animal would be dressed up as a human being to be taken for formal execution by the official hangman.

Bugs on Trial

While domestic animals were tried in secular courts, there was a second type of animal trial.This was the prosecution through the Ecclesiastical (Religious) Courts of natural pests such as swarms of flies, locusts, worms and mice. They were of necessity tried in absentia, though they would be notified of the charges, as was only right.

One famous insect trial took place in Switzerland in 1497. The defendants were insects called the inger, charged with damaging some crops, who were ordered “by the power and obedience to the Holy Church, to appear … at precisely one o’clock … to justify yourselves and answer for your conduct …” Either the inger were not obedient to the Holy Church or didn’t have a handy sun-dial to tell the time, because not one of them showed up at Court. It was left to the lawyers to argue it out.

The defence lawyer claimed, reasonably, that the inger were God’s creatures and so had every right to eat a bit of juicy vegetation when they felt peckish. Unfortunately for the defendants, the prosecuting attorney was slick. He argued that the inger were not included in the animals listed as being on Noah’s Ark, so they must have stowed away on it against God’s will. Therefore they did not have rights as God’s creatures and could be ordered to leave town.

The Judge took this to heart and even told the inger they should be “called accursed” and “your numbers should daily decrease whithersoever you may go.” It seems to have worked. When was the last time you saw an inger?

Did She Do It?

The Defendant Was Wooden

The only part of Europe which didn’t put animals on trial was Britain. However, inanimate objects were another matter.

There is a case on record of a Welsh town putting a wooden statue of the Virgin Mary on trial for murder. It was back in the tenth century, and the statue apparently fell on an unfortunate woman who was kneeling in front of it praying for rain. It was found guilty and dumped by a river, where it got swept away.

The Welsh were following a tradition started by the ancient Greeks, who once charged an Athenian statue with a similar crime. It had been knocked over during a fracas, crushing a young man to death. It was put on trial, found guilty and sentenced to be thrown in the sea.

What Were They Thinking?

Were our ancestors simply nutty? It’s difficult for us now, in such a different world, to imagine what they can have been thinking to put pigs, dogs, worms and even inanimate objects on trial. Scholars have argued that the trials were meant as ‘show-trials’ intended to deter others – humans rather than animals – from committing such crimes.

Others suggest that the trials were a way of enabling people to feel they were establishing control over the natural world, with its frightening unpredictability. By putting animals on trial, invoking the moral laws of the Bible, they brought the natural world under their own law, which was tied to that of the Church and of God.

Did medieval people really believe that statues could have homicidal intentions? Blaming a statue meant people didn't need to blame a human being for whatever had happened. Going through the ritual of trying and punishing the statue, however absurd it might seem to us, could have helped them attain what we now call 'closure'.

These days, when we argue about the treatment of animals, we can look back at medieval days with amusement, outrage or simply bafflement. Compare a society that provides a rat with a lawyer, that endows animals with moral awareness, to a society such as ours, where some dress small dogs up in designer dresses, whilst munching on burgers created by factory farming. Medieval people had it all wrong - but have we got it right?

More on the Same Subject

- The Historical and Contemporary Prosecution and Punishment of Animals

By Jen Girgen, this document examines the historical trial and punishment of animals and looks at what happens today. - Animals on Trial

BBC podcast of radio broadcast about medieval animal trials