- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

Animosity, Division and Hatred in Civil War America - Part 2

Between 1854 and 1860, the Kansas Territory was under the microscope of the entire nation. It strived for admittance into the Union, with the goal of being admitted as a free state, but not necessarily in terms of slavery. Both northerners and southerners flocked to the state, not in defense or opposition to slavery, but simply out of sheer land hunger, to improve his socioeconomic status and to “better our conditions, incidentally expecting to make it a free State.”1 This was the position the country was in on both sides of the sectional conflict – to prosper and expand their way of life, be that northern or southern, but once again, the clashing of cultures in achieving this growth was becoming more and tenser as the months passed.

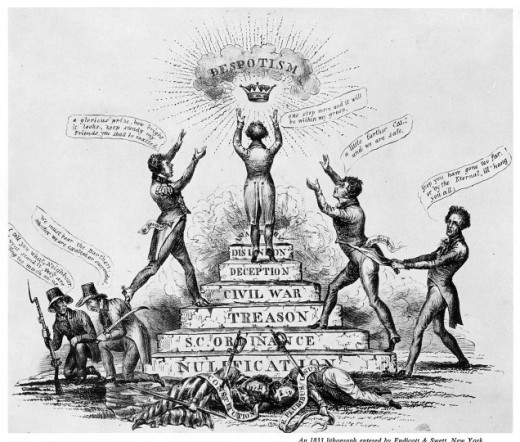

While cultural differences, including slavery, were very important factors, they were not the only factors in the rising tensions that had escalated between the Northern and Southern states. Economically, there were significant issues the caused the animosity wound to fester even further. In 1828, Congress passed the Tariff of 1828, which taxed imported goods with the proposed idea of aiding northern industry from competition outside of the United States, in particular, Great Britain. However, this put the South at a disadvantage, as they relied heavily on the exporting of their staple, cotton, but with the tariffs in place, foreign buyers were less able to purchase from the United States because of the cost displacement.2 The Southerner felt this aided the North at the expense of the South. Congress sought to ease the burden and lighten the harshness of the first tariff by passing a new tariff in 1832; however, the South would have none of it. This led to South Carolina considering the ordinance of nullification, which was also supported by Vice President John C. Calhoun. The state passed the ordinance with the addition that any attempts to enforce the tariffs within the borders of South Carolina would be grounds for the state to secede from the Union.3 Interestingly, it was not just Southern states that followed suit, as some northern states as well, asserted states’ rights to make federal law null and void.

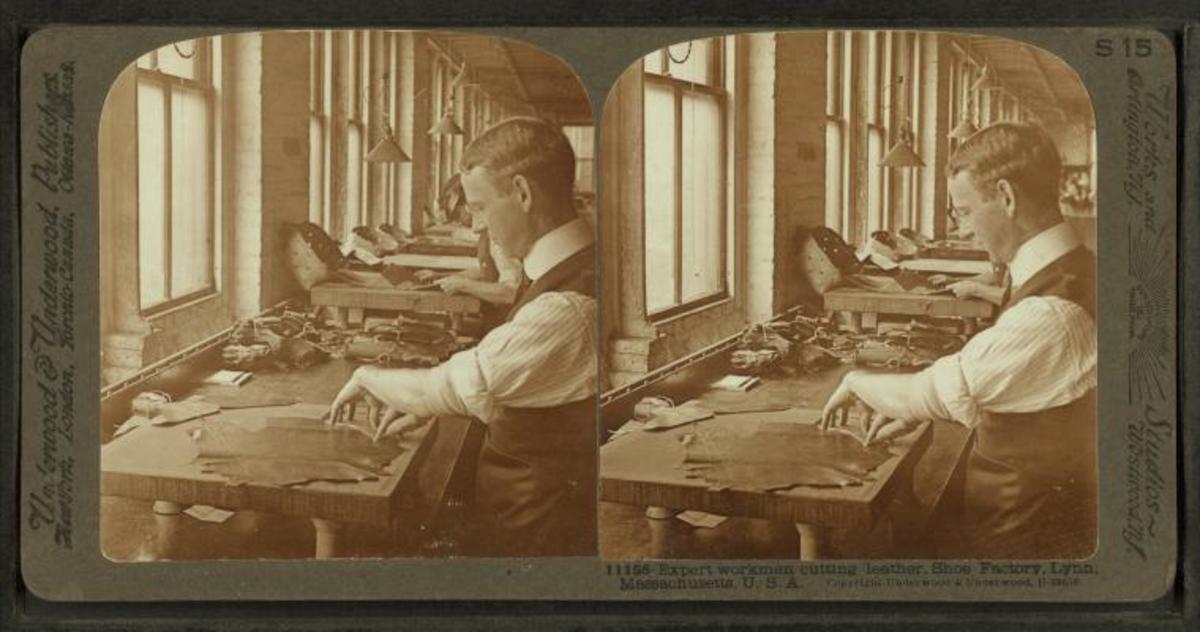

The economic needs of both the North and the South differed in various respects. The South was an agrarian society that relied on cotton as the backbone for its economy and as such heavily relied on slavery as a means for rapid mass production of the commodity. Trade with the North as well as trade with foreign nations was the chief means of capital. It should be noted that the North had a huge economic stake in the cotton and slavery trade. Cotton made up more than half of all other exports from the United States, which benefitted the country as a whole.4 Author Gene Kizer argues that the North’s economy relied on the South remaining in the Union. Northerners were reliant on the South for their wealth and employment, for the manufacturing the South provided, financing Southern agriculture, and more importantly, shipping commodities, that is cotton, around the world. Cotton alone made up 60% of U.S. exports in 1860.5

Professor of Economics and History, Robert L. Ransom seems to agree with Kizer’s assessment that economic issues created very strong regional tensions in the United States. He argues that both the North and South had a great deal to lose by instigating war and that logic from an economic standpoint suggested that a peaceful solution to the division in views of slavery would have made far more sense than a bloody war. Yet no solution emerged.6 There were solutions, but neither North nor South was willing to make concessions.

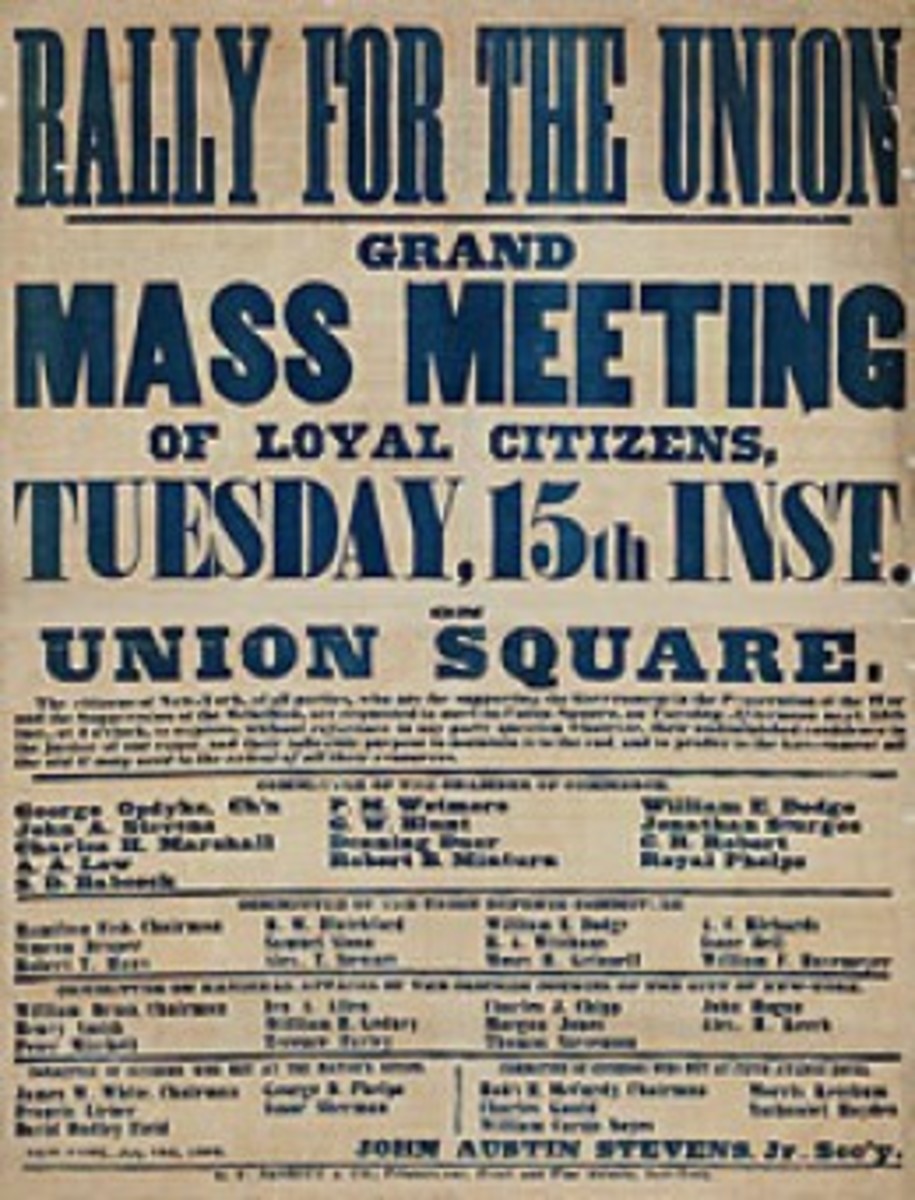

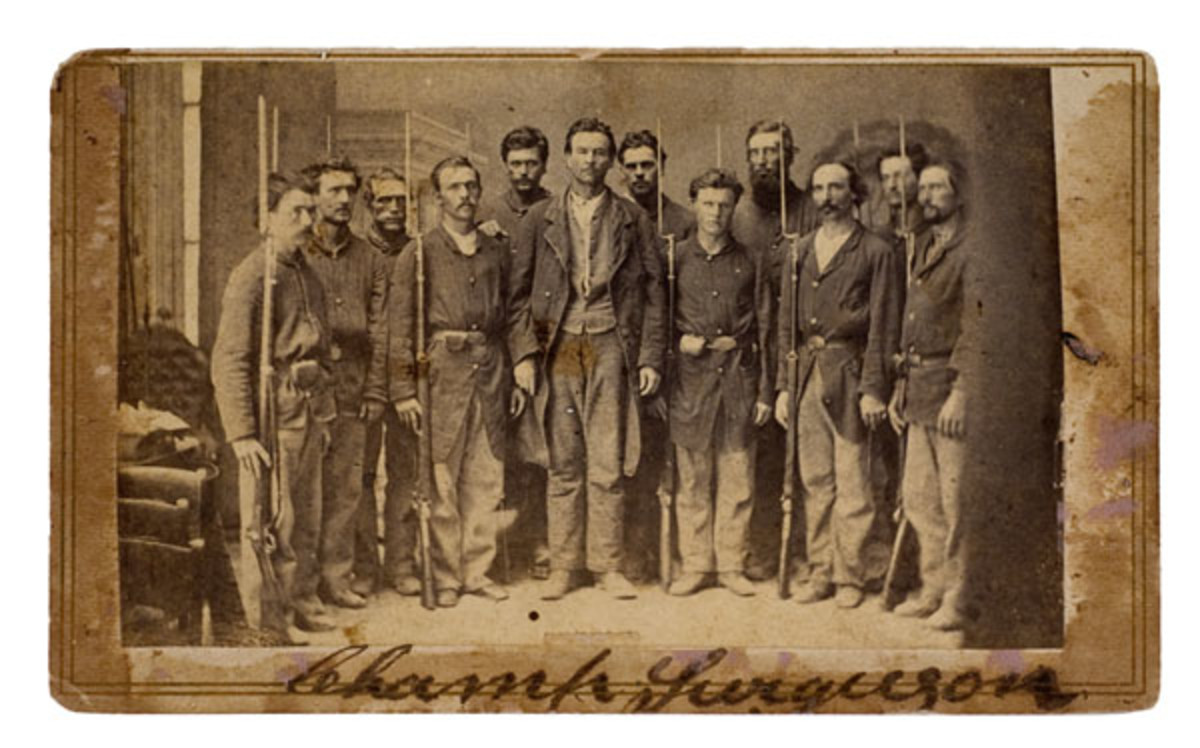

Economics played a pivotal role at the outset of the war in the North, the South and in the West. On April 15, 1861, after Ft Sumter was fired on, President Lincoln called on all the states to render seventy-five thousand men to put down the rebellion. At the time, tensions had risen to the point where the Union Army by 1860 had already enlisted five-hundred thousand volunteers; however, the South had no organized military, yet one-quarter of the Unions commissioned officers left to support the South.7 Economically for both sides, this presented a funding problem for enabling the volunteers to become battle ready. Legislation was passed in an effort to raise troops, with the states footing the bill to later be able to claim compensation from the Federal government, which in turn presented a presence of indebtedness to the states. This became most clear in Missouri and was a major reason why men fought as guerrillas as opposed to regular soldiers. Missouri banks at the beginning had loaned money to the pro-southern government in belief that the war would not last long and that the Confederate cause would be victorious. However, Federal forces quickly seized the state including its treasury and assets, leaving those original loans culpable by those original pro-southern banking individuals and citizens. Now with the loss of slaves, the destruction of the economy, seizure of wartime assets and even theft, left them unable to pay and their loans fell into default. The problem was the Union forces in charge had no intentions of assisting in the repayment of these loans to people considered traitors.8 These are just a few examples of the economic sustainability of both North and South as a major agitator in the animosity divide across the entire nation on an equal level as slavery.

Politically the nation found itself equally at a crossroads. Cushing Strout explains that slavery was part of a larger equation that was intermeshed with other political, social and economic needs and that separating it as a sole factor is simply generalizing the causes of the war. He argues that with granting that the North fought to save the Union and the South for its right to secede, slavery was still a specter that loomed over the Union and needed Southern independence to protect its growth. It wasn’t so much that the war was fought about slavery, rather the war was produced by slavery.9 An example of the entangled nature of slavery and other issues can be found in the Missouri Compromise of 1820. American’s felt the draw of manifest destiny, their rightful roles and masters of their own destiny’s. This continued to play out when additional territory was obtained by the United States. When Thomas Jefferson acquired the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803. The western frontier of the fledgling nation was quickly expanding. The addition of more states had the potential of unbalancing the number of delegates each state had in the Senate, and as such, was critical when it came to the rights of the states as well as their economic needs. For the South, this meant admitting states as slave states that had ties to the rest of the South. For the North it was a matter of pressure from abolitionists and initially to protect the fragile balance between themselves and rapid discontentment of the South. The Missouri Compromise was exactly that, a compromise to unfortunately forestall the inevitable clash between anti-slavery and pro-slavery leaders. What it did, however, was brought a temporary peace, quite similar to what the Founding Fathers did by not abandoning slavery outright.10

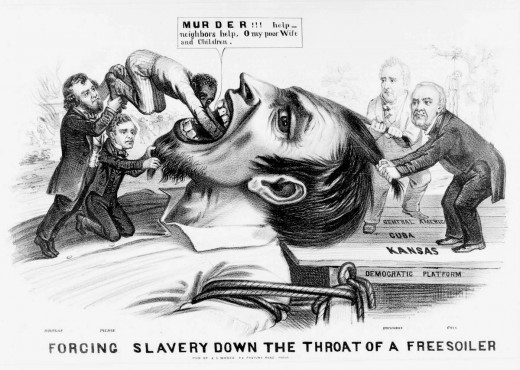

The Missouri Compromise brought a faux sense of peace by setting an actual standard for the expansion of slavery. This peace ended when the Kansas and Nebraska Territories were vying for statehood. Once again, the political balance was being upset and what erupted could arguably be considered the actual beginning of the Civil War. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed in Congress on May 30, 1854 by Illinois Senator Stephen Douglass, and it introduced the idea of popular sovereignty, where the people of these territories would decide for themselves as to their role as a slave or free state. Northerners were outraged as this act in all but words repealed the Missouri Compromise which they felt to be a binding agreement.11 The South were concerned that they would lose both Kansas and Nebraska and thereby lose for more senatorial votes in addition to the ones the North gained with the admittance of California in to the Union as a free state.12 Nebraska was uncontested as it was just assumed it would become a free state per the Missouri Compromise, Kansas, however, was a different story. Northerners, abolitionists, Southerners and Missourians all flocked to Kansas to stack the votes in their favor. Violence erupted on both sides, and murder, deceit, political parlaying, and most of all, hatred, were every day occurrences along the Kansas and Missouri border.

The events in the west so affected the nation, that even in Congress, violence erupted. When Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and an abolitionist, vociferously delivered a speech on what he considered to be the crimes against Kansas and singled out the South Carolina Senator Andrew Pickens Butler as in league with the harlot slavery, the chamber ignited with the cries that Sumner had provoked them enough to “kick him as we would a dog.”13 Two days later, Butler’s second-cousin Senator Preston Brooks, also of South Carolina, beat Sumner almost to death with a cane while other Congressmen just looked on.

Dred Scott was a slave who argued for his freedom first at the state level and eventually all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Scott lost his case on the grounds that the

plea denies the right of the plaintiff to sue in a court of the United States, for the reasons therein stated. If the question raised by it is legally before us, and the court should be of opinion that the facts stated in it disqualify the plaintiff from becoming a citizen, in the sense in which that word is used in the Constitution of the United States, then the judgment of the Circuit Court is erroneous, and must be reversed.14

The outcome of this ruling, by a mainly Democratic Supreme Court, had reverberating implications. Politically, the South believed this to be justification for their legal rights in the Constitution to own slaves. It also opened the door, along with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, for slavery in the territories. In the North, the resolve by abolitionists only increased and it divided the Democratic party along sectional lines, allowing the Republicans a strengthened position. David M. Potter explains in regards to the political events and attitudes of society of the 1850’s that they “offered a telling demonstration that the attitudes of various groups in a society toward upholding the law is in direct proportion to their approval or disapproval of the law which is to be upheld.”15

The final straw came when Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860. Southerners believed that Lincoln’s election meant the end of their way of life as they knew it and rather than submit to Northern control, as this comment in the Atlanta Confederacy newspaper claims, they would rather

Let the consequences be what they may - whether the Potomac is crimsoned in human gore, and Pennsylvania Avenue is paved ten fathoms deep with mangled bodies, or whether the last vestige of human liberty is swept from the face of the American continent, the South will never submit to such humiliation and degradation as the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln.16

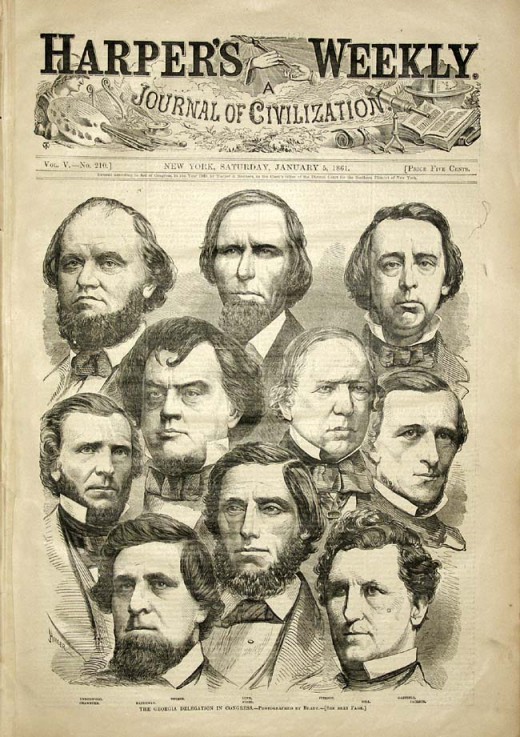

Personal liberty laws being passed in various northern states, while not directly associated with Lincoln’s inauguration, began to come alive across the North and to the ire of an already agitated South, use these laws as justification for secession. Men such as Robert Toombs of Georgia, a leading secessionist, declared that these laws were a direct violation to the Constitution and one step closer to the annihilation of the South and a major cause for the impending disunion feelings across the southern sympathizing states.17 With the fate of Kansas still unresolved and civil war looming on the horizon, the people of the entire nation were in the midst of picking sides for a war they could never have imagined.

Continue to Part 3 HERE

Were Personal Liberty Laws more influential than slavery as an original cause of the war?

Sources

[1] Albert Castel, Civil War Kansas: Reaping the Whirlwind, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997), 3.

[2] Charles River Editors, Secession: The Formation of the Confederate States of America and the Start of the Civil War, (Seattle: Amazon Digital Services, Inc., 2012), Chapter 3.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Roger L. Ransom, "The Economics of the Civil War." Economic History Association, accessed December 1, 2015, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economics-of-the-civil-war/.

[5] Gene Kizer Jr., Slavery Was Not the Cause of the War Between the States:The Irrefutable Argument, (Charleston: Charleston Anthenaeum Press, 2015), chapter 3.

[6] Ransom, The Economics of the Civil War.

[7] Mark W. Geiger, "Indebtedness and the Origins of Guerrilla Violence in Civil War Missouri," Journal of Southern History, 2009, 8.

[8] Ibid., 10.

[9] Lee Benson and Cushing Strout, "Causation and the American Civil War. Two Appraisals," History and Theory 1 (1961), 179.

[10] Potter, The Impending Crisis 1848-1861, 56.

[11] Paul Calore, The Causes of the Civil War: The Political, Cultural, Economic and Territorial Disputes Between North and South, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008), chapter 14.

[12] Donald L. Gilmore, Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border, (Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company, 2008), 6.

[13] Jay Monaghan, Civil War on the Western Border 1854-1865, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1955), 55.

[14] FindLaw, Dred Scott v. Sandford, accessed November 5, 2015, http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/60/393.html.

[15] Potter, The Impending Crisis 1848-1861, 296.

[16] Davis, The Civil War: Brother Against Brother, 116.

[17] Rosenberg, Personal Liberty Laws and Sectional Crisis 1850-1860, 40.