Arabic for Writers and Freelancers

My first exposure to Arabic was in the summer of 2014 when I was living in San Francisco and working in a cigar shop because it was something to do while I was behind the counter with my supervisor, who was a Christian-Arab from Jordan. I remember when he first wrote out each of the letters, right to left. Many people think the letters are symbols, but they’re not. They’re just entirely different letters than Latin language speakers are used to seeing.

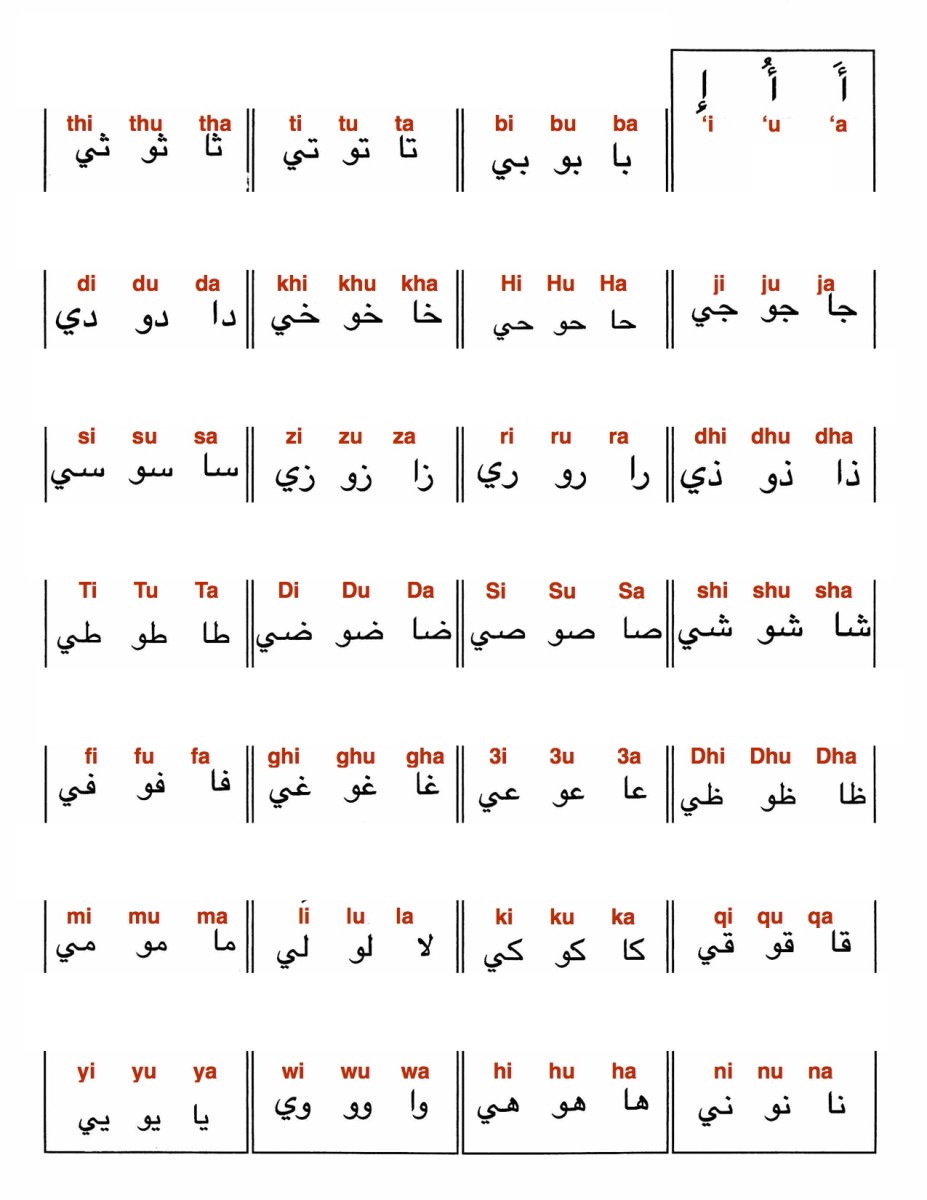

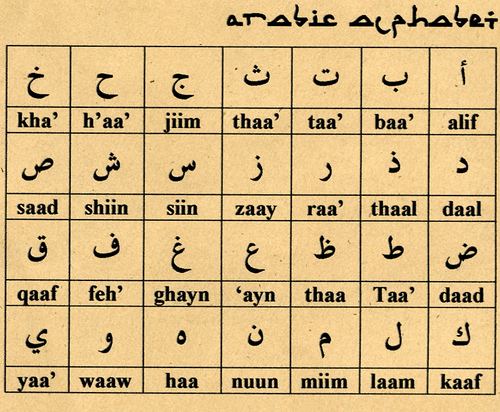

There’s twenty-eight letters in the Arabic alphabet, whose appearance, and most of whose sounds are totally unfamiliar to most other languages in the world. I spent plenty of time behind the counter reciting the alphabet, and writing and re-writing the alphabet from right to left until I had filled dozens of pages in my notebook.

I put it down in the fall. I couldn’t really tell you why I picked it up in the first place. Practicing brought great gratification, but realistically, I didn’t have time to learn Arabic for the fun of it. It’s a very difficult language, and learning it requires dedication.

I picked it up again in the spring of 2015. Yet again, there was something I couldn’t put my finger on that drew me to the totally foreign script. When I picked it up a second time it was about accomplishing a goal.

I took to the language with a fervor, but even still, a bit like a fool to think I could learn it with only five-ten hours a week to practice.

That being said, I had learned enough to make this endeavor much more manageable.

There’s 28 letters in the Arabic language, but each letter has four forms. There is the isolated form, which is a letter standing by itself. There is the initial form, which is the letter when it begins a word. There is the medial form, which is the letter in the middle of a word. And there is the final form, which is the letter when it ends a word. If you do the math, that is 112 letters of their four forms to learn; but there are some that are easily recognizable in their initial, medial, and final forms, from their isolated form; like the first letter of the alphabet, “alif” whose initial and medial form is exactly the same as its isolated form; and its final form is easily recognizable. Learning the alphabet is the first challenge; I was able to do so much quicker with a method that I had developed, rather than what the instructor of the YouTube video was recommending. He was a very good teacher in general. Great, actually, as he had a way of being able to really connect with a virtual audience. Listening to Jazz or classical music while studying was also helpful.

I hadn’t taken any classes, and I didn’t have much assistance with the exception of my former supervisor in San Francisco (who would make a s*** tutor) and another former coworker of mine back in the Chicagoland area in the summer of 2015, whose name was Omar. He was an Indian-Muslim (I never asked what sect) with a Masters in Biochemistry that he had earned in Australia. He actually didn’t regard himself as a fluent Arabic speaker; he told me this every time I had a question, and I always responded: “You know more than I do, and you know what I’m asking. Thank you for your help.” He really just helped me with questions I had here and there, but he was of great help here and there. Most of the teaching I’m getting now is off of YouTube.

I’m starting from the very beginning, but I’m only noting the things that don’t come back to me with ease, so I don’t think it’ll take me long to get through. The instructor, again, is pretty great otherwise. He mumbles sometimes, but he speaks fluent, and clear English; and more importantly, clear, modern standard Arabic.

I left a comment one day regarding the method I developed myself to learn the alphabet, advising him to use it. He had been advising his viewers to perform repetition exercises; simply writing and re-writing each letter in each form until your hand gets sore. I found my method to be much more effective for the fundamental phases.

I had an Arabic-English dictionary, which had a selection of reference tables in the beginning (the alphabet, numbers, months, days, years, units of measurement, etc.) and I’d go through the dictionary, pick a semi-random word (I tried to stick to groups: colors, seasons, or days of the week for example, which is a common way of learning vocab in any language) and write the word in my notebook. As I wrote the word, I tried to recognize each letter without having to look to the reference tables. With this method, I was able to practice writing, letter recognition, and vocabulary in one drill.

However, I didn’t have the time to learn Arabic simply for the sake of accomplishing it either, as sad of a day it was that I admitted that to myself. I was picking it up pretty quickly for the amount of time I had, too.

Aside learning the alphabet, there is also learning the vowels, as well as what I call “hybrid vowel-letters.” I still have a hard time explaining the difference between the “hybrid vowel-letters” from being simply vowels, or letters. A simple vowel such as “Fatah” which appears as a dash above letters produces an “ah” sound of that letter it sits on top of. There are other such simple vowels, such as a “Sukun” which appears as a circle above certain letters, and produces a long vowel sound, similar to an “ee” in English. If you put them together, the “Fatah” first, and then the “Sukun,” you make what is called a “diphthong,” which is making a different, but singular sound of two vowels, similar to letters “oi” in the word “coin” in English. Then there is the “ta marbutah.” Depending on where it is in a word, it either makes a “taa” sound or a “haa” sound.

For some reason, I’d never given serious consideration to knowing Arabic professionally. I’m a free-lancer, and aside the fact that I’ve entirely re-focused my work to revolve around Islam, I still should have considered that there’s a lot of free-lance work available for people that are bi-lingual.

Most of the work is for translation, interpretation, and ESL teaching positions (English as a Second Language); the demand ultimately depends on the language. Arabic speakers are in high demand, but much to my dismay, the pay doesn’t seem to increase from interpreting Spanish to interpreting Arabic, but that can be seen as encouraging for those that aren’t interested in learning a language as challenging as Arabic, because everyone can expect at least $15.00-$20.00 per hour with translation and interpretation jobs, or teaching ESL. Thirty dollars an hour even once you get some experience. I came across a lot of virtual work (ESL classes conducted via Skype) which was pretty encouraging as well.

I remember my first night of job market research. The flickering feeling of inspiration was all too familiar.

Perhaps the best part is that it’s all very accessible. One doesn’t need a degree in Arabic, Spanish, or German to be a translator or an interpreter. They only need to be fluent: no $100,000 degree required. TESOL certifications to teach ESL courses are around 30 credit hour programs of which many community colleges offer, of which I don’t even need to be fluent in Arabic to teach English to Arabic speakers. It will be a great learning opportunity, and once I feel confident enough, I’ll take an Arabic Proficiency Test to demonstrate to future clients that I can interpret and translate Arabic to English.

I’m not the first free-lancer to have explored teaching ESL courses.

If someone offered you the opportunity to spend the next two years in Cyprus to learn Arabic, all expenses paid and stipends matching your current income were offered, would you go?