- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

Common Valor: Artillery Heroes in WWII and Korea

Heroes come in all shapes and sizes. Some are born to it. Others are in a desperate situation and forced to act. In James Michener's book, The Bridges of Toko Ri, the character of Admiral Tarrant sadly laments after the death of one his pilots, "Where do we get such men?" We will never truly know. Humans just react, sometimes to save another or just themselves. The men listed below are just a few of the thousands who gave their lives for their fellow GIs.

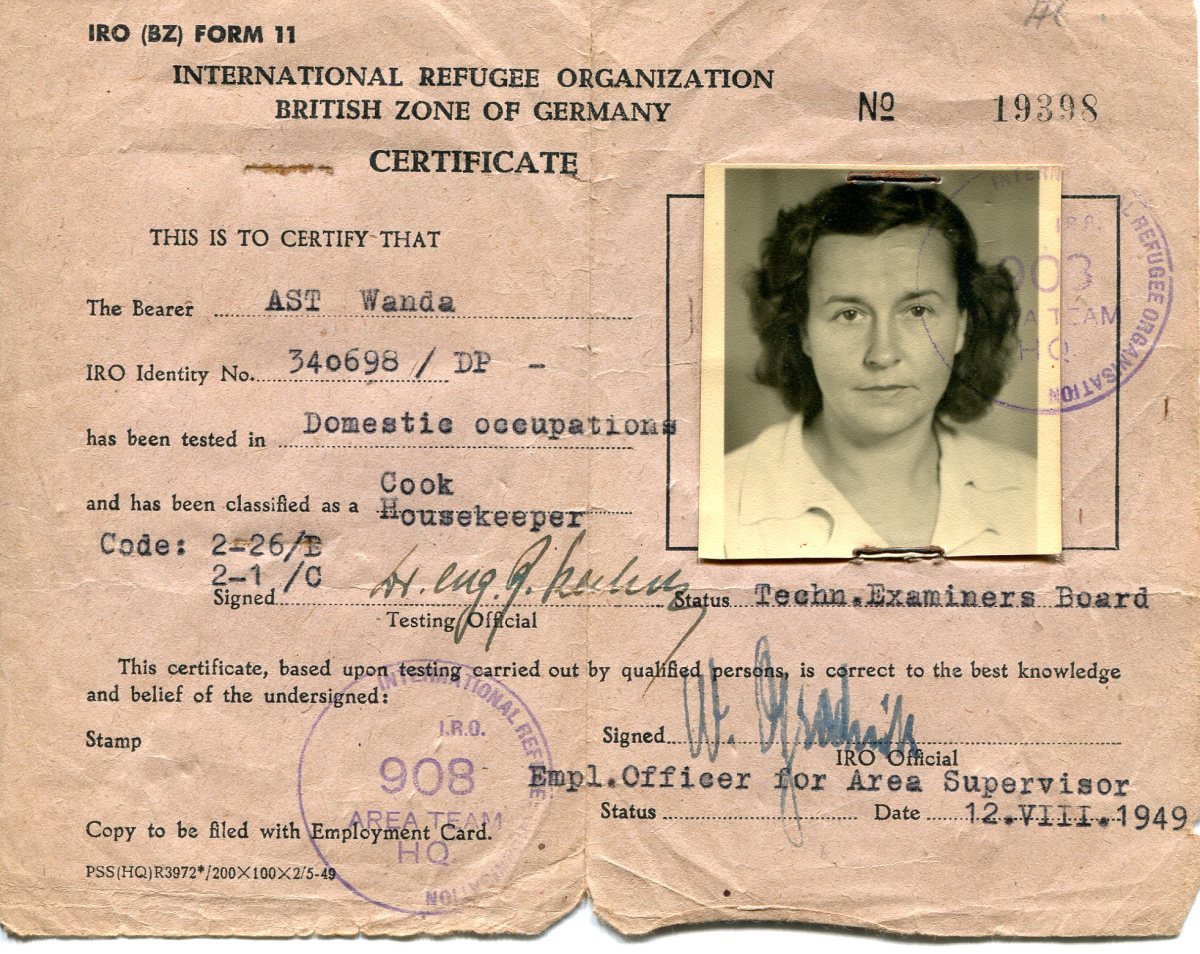

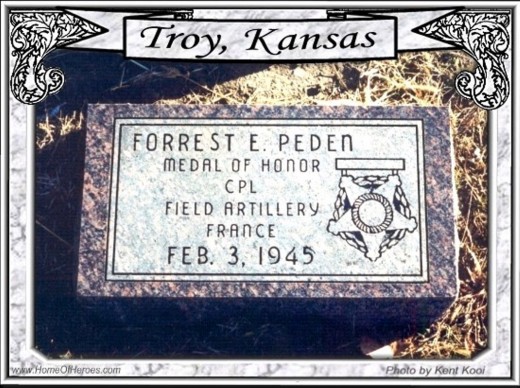

1. Forrest E. Peden

The 3rd Infantry Division suffered one of the highest casualty rates in World War II, and as a result had a large number of Medal of Honor winners throughout the Division. One of those was Missouri native Forrest Peden of Battery C, 10th Field Artillery Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division.

Technician Fifth Grade Peden was with his forward observation team near Biesheim, France on February 3, 1945 as darkness fell on Saturday, February 3, 1945. The team was advancing with a platoon of infantry when the Germans sprang an ambush. The Germans outnumbered the GIs 4 to 1. Artillery, mortars and MG42 fire rained down on the trapped men. Those who dove for the ditches at the side of the road found them full of enemy troops. Hand to hand combat ensued. Peden kept his wits about him, running to aid two wounded men. Despite shrapnel swirling around him, he managed to stabilize the soldiers.

The observers needed to call for fire but their radio was destroyed in the initial barrage. A runner was needed. Peden volunteered. He ran half a mile back to the Battalion Command Post. Along the way bullets ripped his jacket, but missed his body. Two light tanks volunteered to go forward but they needed a guide. Peden hopped aboard, exposed to the hail of fire. Peden wanted to use the tanks to not only fire at the Germans but evacuate the wounded or at least cover them until the firefight was over. Just as they arrived at the ditch, Peden’s tank took a direct hit from an anti-tank round. The blast killed Peden. The tank became an inferno. But the glow of the fire helped guide the rest of the relief force which helped drive off the enemy.

Peden is buried at Mount Olive Cemetery in Troy, Kansas. His brother Lavern was also killed in WWII.

2. George B. Turner

George Turner was not your typical soldier in World War II. His background was unique and varied. He was also one of the oldest men ever to receive the award. Not many 43 year olds were showing up at the enlistment center in 1942. But Turner was determined to fight in this war because he had just missed the last one.

A native of Longview, Texas, Turner was educated at the Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington, Missouri. He joined the Marine Corps during World War I, but the war ended before he could be sent overseas. During the 1920s he moved to California, where he worked as a legal secretary for a law office. Unmarried with no children when the US entered the war, he was eager to get into the fight. He was assigned to the 499th Armored Field Artillery Battalion of the 14th Armored Division.

On January 3, 1945, a German panzer grenadier unit attacked the town of Phillipsbourg, France, almost surrounding the 499th. Eventually Turner was cut off from the rest of his comrades and tried to make his way out. . He met up with a friendly infantry company withdrawing under murderous fire, when he noticed two German tanks and approximately seventy-five supporting foot soldiers advancing down the main street of the village. Seizing a bazooka, he advanced under the withering small arms and cannon fire to meet the tanks. Standing in the middle of the road, he fired at them, destroying one and disabling the second. But he wasn’t done. The German infantry was still coming. Thinking fast, he leapt onto a half track, and dismounted the machine gun. He then placed it in the open street and fired into the grenadiers, killing or wounding a great number. The attack was broken.

He waited for the inevitable American counterattack which soon followed. But then two Shermans were disabled by an enemy antitank gun. Firing a light machine gun from the hip, Private Turner held off the enemy so that the crews of the disabled vehicles could extricate themselves. He ran through a hail of fire to one of the tanks which had burst into flames and attempted to rescue a man who had been unable to escape; but an explosion of the tank’s ammunition frustrated his effort and severely wounded him. Refusing evacuation, he remained with the infantry until the following day, driving off an enemy patrol with serious casualties, assisting in capturing a hostile strong point and voluntarily driving a truck through heavy enemy fire to deliver wounded men to the rear aid station. It was a miracle that he survived.

Turner was the only recipient of the Medal of Honor from the 14th Armored Division during World War II; at 46, one of the oldest. During the award ceremony, President Harry Truman expressed his jealously when he said: "I would rather have that medal than be President of the United States."

Mr. Turner died in 1964 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, section 41, lot 589.

The Ultimate Honor

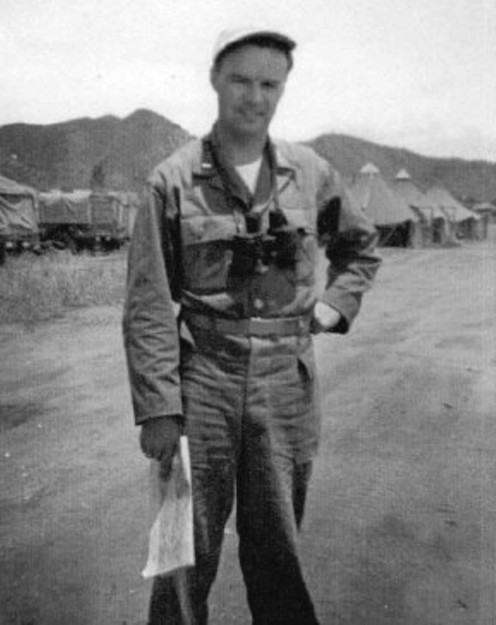

3. Lt. Lee R. Hartell

The Korean War is often referred to as the artillerymen’s war because of the mountaintop duels that lasted for days. Fighting off the North Koreans and Chinese troops depended a lot on the calm demeanor of an artillery observer. First Lieutenant Lee R. Hartell was one of those men. Raised in Connecticut, Hartell was a veteran of World War II, serving with the Army in the Pacific. He had broken a family tradition of serving with the Navy. After he came home, he joined the Connecticut National Guard, eventually receiving a commission as a second lieutenant. He then transferred to the regular army as a sergeant where he eventually received a regular commission back to lieutenant.

The 28 year old was assigned to Battery A, 15th Field Artillery of the 2nd Infantry Division. His observation team was working with B Company of the 9th Infantry, at the base of Hill 700 near Kobangsan-ni, Korea on August 26, 1951. B Company had just taken the area, so concerns about a counterattack by the Chinese were very real.

Just before dawn on August 27, their fears were realized when the Chinese attacked in waves. Hartell immediately left his outpost and ran to an exposed part of the ridgeline for better observation. First he called for flares in order to illuminate his targets. Then he began calling in fire missions. Hartell was able to walk the artillery fire right up side of the hill, dispersing the enemy infantry. But they kept coming, getting within 10 yards of his position. Suffering a severe wound to his hand, he grabbed the microphone with his other hand and continued calling for fire. “Fire for effect!” was heard often that morning. It seemed as though thousands of enemy troops were now rushing up towards the ridge. His original observation post was soon overrun and he now faced an agonizing decision. During his final radio call, he called for continuous fire from both the batteries that were supporting them. He essentially called his fire down on his own position. At 0630, while speaking to Battalion, a bullet pierced his chest. The line went dead.

Lt. Hartell is buried at the New Saint Peter Cemetery, Danbury, CT. The Connecticut National Guard has named its installation in Windsor Locks in his honor.

Sources

- Zabecki, David T. American Artillery and the Medal of Honor. Merriam Press (Bennington, VT. 2008)

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=7989590

- http://www.14tharmoreddivision.org/medalofhonor.htm

- http://www.ct.gov/mil/cwp/view.asp?a=1351&Q=515162

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=7841433

- militarytimes.com

- http://www.landscaper.net/korean.htm