Ba'al's Influence on YHWH

A study of the relationship between Ba’al of the Canaanites and YHWH of the Israelites needs to be examined from two perspectives: Biblical tradition and scientific evaluation through available archaeological data. The cultures of the Canaanites and the Semitic invaders known later as the Hebrew and the Israelites, combined to create a living and evolving faith. A brief examination of their histories during the time of the Patriarchs and of the Exodus aides in understanding how Ba’al influenced YHWH.

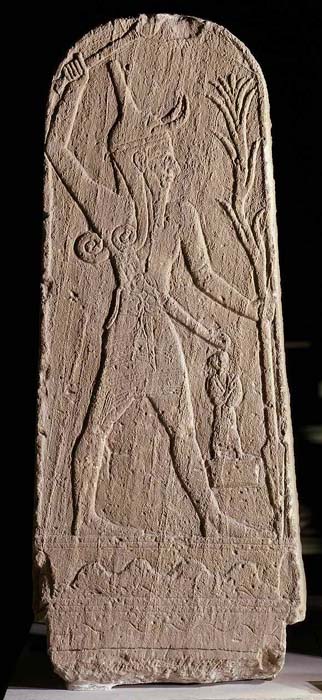

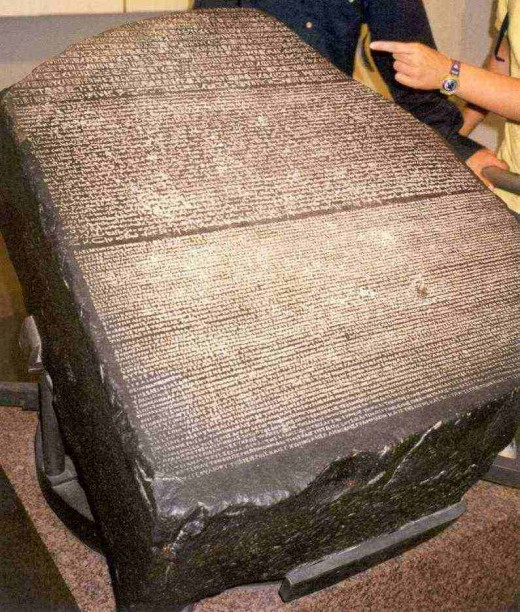

In the Oxford Reference Encyclopaedia Ba’al is a “Phoenician god of fertility, the storms and winter rains…” with a general meaning of “lord”. The name can be “applied to any male fertility gods whose cult was widespread in ancient Phoenician and Canaanite lands” (113). Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable defines Ba’al as the “…chief Semitic fertility god…”, and continues with: “There were also local Ba’als, such as those established in Canaan when the Israelites arrived. The latter adopted many rites of the Canaanites and grafted them to their own worship of Yahweh …. It was this form of worship that Hosea and other prophets denounced as heathenism”(80). The Harper Collins Dictionary of Religion describes Ba’al as “a common Semitic noun meaning ‘lord’ or ‘husband’” (99). Texts such as the Rosetta Stone, the Behistun Inscription and the Amarna Letters provide additional sources to the traditional Bible. They give textual collaboration and further information of the time, people and culture, including the interaction of Ba’al and YHWH.

Ba'al, Yahweh and Their World

Ba'al, YHWH and Habiru

- Habiru - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Habiru - Tetragrammaton - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

YHWH - Baal Worship in the Old Testament

The Canaanite storm god Ba'al and the background of Ba'al worship in the Old Testament.

Ba'al and El

The study of Ba’al must be considered within the larger context of Canaanite religion. Belief in a guiding divinity within Canaanite culture was polytheistic in nature. The Canaanites were unable to believe that one god could control such a diverse world. Each area and village, craft and aspect of life was represented by a deity. Yet the gods were regulated by a rivalry with other gods keeping their omnipotence over man in check. This rivalry between gods mirrored the warring action between states and cities and although it didn’t offer security, it helped to explain their natural world (Grant 22). El ruled this anthropomorphic pantheon of over thirty gods and goddesses.

In most Semitic languages ‘El’ translates as ‘god’ or ‘mighty one’. Also known as the Bull because of his strength, El, like YHWH, remained “wise, beneficent, kindly, and merciful” (Grant 22), and humanity was expected to emulate his qualities. In particular the monarchs were to perform rites to secure “forgiveness for their sins and offences” (Grant 22-23). Such aspects of Canaanite kingship would later become ingrained within the Israelite culture (Grant 23).

El’s potential in the Canaanite culture for being monotheistic was overshadowed by the localised nature of his cult. He was worshipped as El Shaddai around Hebron, as El Bethel at Bethel and as El Olam in Beersheva (Grant 23). In Jerusalem he was worshipped as El Elyon translated as “creator or owner of heaven and earth” (Grant 23), but the popular polytheistic belief regarded these as regional deities, rather than one all powerful god. The Canaanites’ acceptance of many gods included El’s son Ba’al who proved to be a major force. Ba’al was youthful and dynamic and assumed El’s role. Eventually his worship evolved into agriculture where he “became the god of the vegetation promoted by the tempests over which he presided” (Grant 23). He became master over earth’s land and water and engaged in a seasonal life and death struggle with Mot who dried up the soil and vegetation.

In opposition of this natural, cyclical religion, the Yahwist religion became rooted in the Hebrew national history “directed towards a determined end” (Grant 24). YHWH was the eventual centre of the tradition. His origin is unclear. Whether he was the god of the Kenites or Midianites living near Mount Horeb (Friess 254), his worship and priesthood wasn’t established until the Exodus tradition. Prior to this period, religion among the Semitic nomads, of whom Abraham was a member, was represented in the clan’s patriarch “establishing … a personal and contractual relationship … [with the] clan god” (Bright 98-99).

The Patriarchs

The biblical patriarchs’ gods were called the God of Abraham, the Fear of Isaac and the Champion of Jacob. These patron deities of clans are documented in Genesis, and in chapter 31, verse 53 Jacob and Laban “… swear(s) by the God of his father’s clan” (Bright 98). The god of the clan was viewed as its invisible head, and through various personal names of the time it is obvious that the Hebrews followed their god under the name of El (Bright 99). Names such as Ishmael – May God hear – or Jacob-el –May God protect – tie in with Canaanite shrines of El Shaddai, El’ Olam, and El’ Elyon. When the Hebrew nomads of Abram’s era moved into the Canaanite lands their clan gods, because of similar traits with the native gods, came to be identified with El (Bright 100). Identifying with the local gods probably resulted from a desire to appease them, and keep the peace with their new neighbours.

How the patriarchs came about their new land and neighbours is traditionally immortalized within the Bible. Terah moved his family from Ur to Haran where after his death Abram, his son, was instructed by God to: “Get thee out of thy country, and from thy father’s house unto a land that I will show thee: And I will make of thee a great nation, … and they went forth into the land of Canaan; and into the land of Canaan they came” (Genesis 12:1-5). Consequently Abram, or Abraham, as a recipient of God’s call and an obedient servant came to be regarded as the father of a people. His life became the embodiment of what a principled life should be. To this day Jews still call him ‘Father’ in their prayers, and Islam believes him to be El Khalil, or God’s friend (Grant 31). Yet the reality, according to information corroborated in other textual evidence, doesn’t contain quite so many details.

Archaeological evidence suggests the Hebrews were the habiru, semi-nomadic drifters who may have served the settled Canaanites in a variety of ways – mercenaries, slaves and/or raiders (Grant 29). They were comprised of a Semitic mixed race. It is believed the patriarchs were “part of a much wider socio-economic class of ‘sojourners’ bearing that name [habiru]” (Grant 29), and that they were a later wave of immigrants after the Amorites. They are generally thought to have arrived in Canaan around the year 1800 BCE. The tribal deities they brought with them, tied as they were upon people and not places as in the Canaanite culture, seems to have been the secret to the success of their religion. The later Mosaic, or Exodus, generations would be bound together on this premise and made into the “great nation” promised to Abraham.

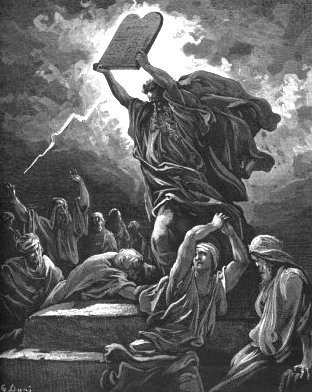

On the way to becoming a great nation, Israel passed through the doors of famine, and later slavery within the Egyptian context. According to Biblical tradition Joseph, the son of Jacob, was sold into slavery by his jealous brothers and arrived in Egypt where he gained favour and prestige. Famine forced his family to Egypt where they settled, and for four hundred years their numbers grew, until a king of Egypt took advantage of their numbers and pressed them into labour. At this point Moses freed his people, and moved them back to Canaan through the Sinai where the unique faith of YHWH came to be expressed.

Moses, YHWH and The Covenant

Some scholars believe Moses discovered YHWH through his father-in-law Jethro – a Midianite. This connection seems to be valid given the discoveries at the copper mines in Timna, south of the Dead Sea where the Midianites continued to mine after the Egyptians left. They replaced the Egyptian temple of Hathor with their own tent shrine, and Hathor sculptures were defaced or thrown out. Similar practices of shrines as tents and the banning of images are well known tenets of Israelite belief (Bright 127).

Although we can’t be sure that a god called YHWH was worshiped prior to Moses, we are certain that through the efforts of Moses “Yahwaism was completely transformed and given new content” (Bright 128). After Moses’ death, Biblical tradition states Joshua led the Israelites into Canaan. Archaeological data tells us the conquest was more gradual and less dramatic.

Cultural Fusion

After the initial conflict resulting from the Israelite invasion, life became more peaceful between them and the native Canaanites. The Israelites gradually adopted Canaanite agricultural practices, while some continued as the herdsmen. A certain amount of intermarriage took place along with some “cultural fusion” (Friess 255). In the main, the Israelites became a poorer farmer class whereas the Canaanites withdrew to their fortified towns and “engaged in trade” (Friess 255). A mingling of religions was, once again, bound to occur.

A cult of “high places” including sacred groves and stones grew out of the localised religion and became popular (Friess 255). The religious calendar was given an agricultural structure. An example is found in the Feast of the Unleavened Bread being added to the Passover of Mosaic tradition. Animal sacrifices became more elaborate, and fertility rites became common.“Sacrifice of first-fruits and redemption of the first-born were taken over from the Canaanites” (Friess 255). The goddess Ashtar was worshipped and considered the consort of Ba’al-Yahweh (Friess 255). YHWH’s jealousy tempered toward the Baalim or gods of the land, as “local shrines were taken over by his priests, the Levites, who at the same time maintained at Shiloh the national shrine containing the Ark of the Covenant” (Friess 255). Thus YHWH took on new characteristics, but his national prestige as supreme deity of all tribes persisted and therefore the priesthood grew.

In the four hundred year interval between the time of the Patriarchs and the time of Moses, the Hebrew faith underwent changes, yet kept its people conscious of themselves and their history, which in turn led to their longevity as a nation. These changes included modification from their original individual clan deities, to an individual all-inclusive god who guided them by way of charismatic leaders. Wisely, various leaders incorporated details of other faiths found in their adoptive lands which often proved to strengthen the evolving Hebrew faith. Because this faith was based on a people and their challenging history, it endured. Within the context of ancient history, Israel’s place is small, but from these scattered tribes of nomads have arisen the major religions of the world including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Ling 12). Even though Ba’al and El have gone the way of ancient history, they still in some small manner remain a part of modern times through their influence upon the ancient Israelite faith and culture.

Bibliography

Bright, John. A History of Israel (fourth edition). London: Westminster

John Knox press, 2000.

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Millennium Edition. 2000.

Friess, Horace L., and Herbert W. Schneider. Religion in

Various Cultures. New York: Holt and Company.

Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel. New York:

Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1984.

Harper Collins Dictionary of Religion. 1995.

Ling, Trevor. A History of Religion East and West. London:

Macmillan, 1968.

Master Reference Bible; King James Version. Nashville

Tennessee: Royal Publishers, In., 1968.

Oxford Reference Encyclopaedia. Oxford University Press.

1998.