Battles of the Hundred Years War: Muddy Bloody Drama at Agincourt

By Nils Visser

The article Arrow Storm at Azincourt looked into the expected Battle of Agincourt anniversary events in 2015. This article is a short exploration of the factors that make this battle so special.

A significant contribution to the status of Agincourt was made by Henry the Fifth’s propaganda machine. Let’s face it, the English army wasn’t in France with very honourable intentions, it was all about power, land and loot. However, any politician worth his salt is be able to garnish such goals with lofty aims and varnish it with heroic intentions, and Henry the Fifth proved to be a skilled politician. He managed to turn what was pretty much an application of havoc and mayhem into an almost divinely inspired business venture. Upon his return in England he made sure he was preceded by minstrels acquainting the populace with the newly written Agincourt Carol, “Deo Gratias Anglia redde pro Victoria” (thank the Lord oh England for this victory).

But to be frank, the general populace is seldom as thick as those in power like to think, and it is unlikely that the English population would still have such a strong collective memory of the Agincourt campaign simply because a politician employed some very smooth spin. For almost three hundred years Europe had been dominated by mounted ruffians, whose major job requirement was to have an aptitude for violence. King Richard the First, of Lionheart fame, generally celebrated as a great king, was, in his own day, renowned for being able to hew an enemy skull down to the jawbone, try adding that to your resume as an additional skill today! This horde of hoodlums had developed into the nobility, who were increasingly learning to disguise their inherent violence with fancy stories and pretty rhymes about patriotic heroism, but who, in all fairness, were hardly very conducive towards the wellbeing of the people they ruled.

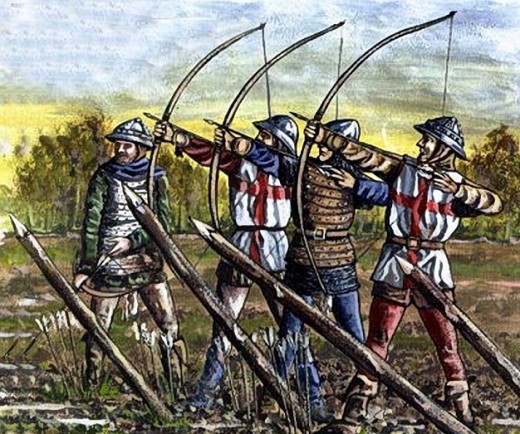

The English archers represented a shift in social status and interaction. They were from a simple background, but not quite the villeins and peasants they are sometimes made out to be, these were the yeomen, the skilled craftsmen who formed a very early prototype of the Middle Classes. And these fellows managed to defeat the expensively dressed and fancily titled nobles time upon time upon time.

Henry the Fifth’s army had already been weakened by dysentery, the knights and men-at-arms in particular had suffered badly, which gave the already numerous archers a considerable preponderance in the English army. A reasonable estimate is that Henry commanded 900 men-at-arms, and 5,000 archers. Facing this force was a French army of some 30,000, mostly men-at-arms. The latter considered the battle as good as won, in their mind there were only 900 serious opponents, namely those of a similar social status. Because the centre of the English line at Agincourt, formed by 900 or so men-at-arms, offered the most opportunity for ransom, honour and glory, it was this part of Henry’s army which would be the focus of the French assault. Then, from the flanks, came the arrow storm.

The average archer could loose 15 arrows a minute, calculate for a moment what will happen when 5,000 archers do this simultaneously. The French flanks, mounted on horses, attacked the archers but succumbed to the arrows, after which the archers aimed their arrows at the much larger centre formations of the French army, these were dismounted and struggling greatly, torsing 60 to 70 pounds of armour and equipment through the wet clay which had been recently plowed. The arrowstorm forced them into a funnel. Once they reached the English men-at-arms many of the French didn’t have the space to swing their weapons, tightly constricted as they were by their neighbours, moreover, their comrades behind them pushed them straight onto the English blades. A veritable massacre followed, and a very convincing victory for the smaller and supposedly weaker army.

Agincourt is special because it is surrounded by high drama. We have a young warrior king, who, as we have been told, was not too lofty to mingle with the ordinary troops and talk to them and with them. Then there is the predicted outcome of a battle in which a much smaller and ostensibly weaker army is very likely to be overwhelmed by a numerically superior opponent, which is subsequently annulled by aristocratic arrogance, highly skilled specialists and mud, lots of mud. It is natural, human, to side with the underdog, and pleasing when David defeats Goliath. Last-but-not-least, Agincourt represented the victory of the common man, not unimportant in an England in which there were great discrepancies between Norman nobility and Anglo-Saxon commoners. The lesson taught by Agincourt was that England was strong if the two worked together, and if there was an acknowledgement that the commoner had a useful and necessary role to play. It wasn’t a coincidence that Shakespeare’s Henry (The Life of Henry the Fifth) had a mouth full of the brotherhood between men regardless of the status given to them by birth, of the equality he perceived within the happy few within his band of brothers. This is something intuitively recognized by the populace, and this the reason that the old battle cry still finds resonance, “For Harry, England and Saint George!”.