Brassicaceae

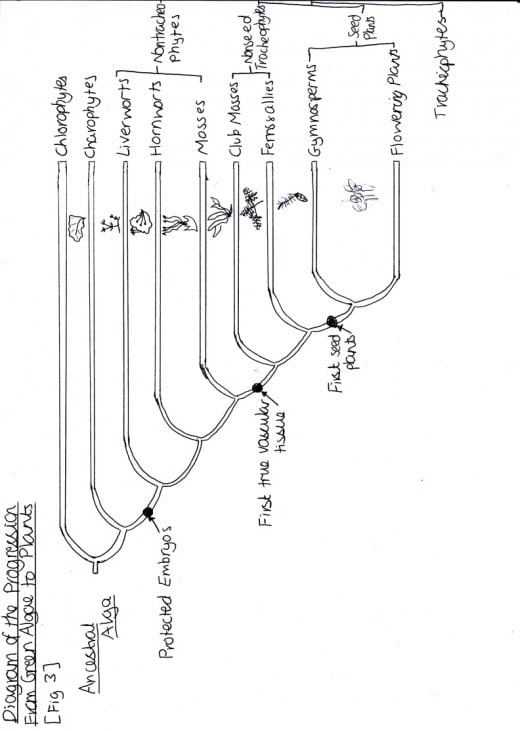

Figure 1: Diagram of the Progression from Green Algae to Plants

Click thumbnail to view full-size

Observable Differences Between Lower Plant/Gymnosperm Tissues and Angiosperm Tissues

There are observable differences between the Angiosperm stem (Hydrophyte, Potamogeton) and the Pinus stem (young, in first year). Firstly, the Pinus stem contains resin ducts for the production of resin. Resin is a substance which protects the plant from insects however other substances, such as latex, are more common in Angiosperms. Also, I think the resin ducts are not present in the Potamogeton, in particular, because it is an aqueous plant and so the sticky resin would turn to liquid, rendering it useless. A further difference is that there seems to be greater percentage coverage of vascular bundles in the Angiosperm than the Gymnosperm. This could be because in the Gymnosperm, there will be a large amount of secondary vascular tissues, as the Pinus ages, eventually becoming ‘wood’, when the Angiosperm will not do this.

There are also difference which can be observed between the Angiosperm leaf and the Gymnosperm (Pinus) leaf. The Angiosperm has a thick cuticle when the Gymnosperm does not. This is because Angiosperms developed later in the evolutionary history and so have the cuticle to be more adapted to survive further away from water [Figure 1]. Also, the Gymnosperm leaf contains only two vascular bundles when the Angiosperm contains many. This could be further evidence for the Gymnosperm being less adapted for terrestrial living, since it is not as prepared for the necessary water uptake.

The third set of observable differences are between the lower plant (Marchantia Sporangium) and an Angiosperm. The Liverwort had no chlorophyllous tissues or stomata. This is because they are completely reliant on the parent gametophyte for their nutrients. Thus, they have no chlorophyllous tissue because they are unable to do photosynthesis and have no stomata to protect themselves against water loss. However in Angiosperms, the sporophyte is the main part of the life cycle so it is able to do photosynthesis and it does contain these structures.

Methodology of Growing Brassicas

The methods used to grow the Brassicas: Firstly, four wicks were thoroughly wet and then placed into the bases of four minipots so that about 0.5-1 cm extended from the base of the pot. While the holes under the minipots were covered, the minipots were half-filled with growing mix. This mix was then pushed down into the corners and three NPK fertiliser pellets were laced in each minipot. After this a small amount of growing mix was added to the top and then pressed down gently. Three seeds were then placed into each minipot, followed by enough growing mix to just cover the seed. Then the seeds were pressed upon gently to ensure they were all covered. A label including details such as the name of the planter and the date was added to the four pots. Finally, the plants were watered from above until the water dripped through from the wicks and put 5-7 cm below lights, where water was pipetted to them every two to three days.

Description of the Life Cycle of Rapid Cycling Brassicas

Brassica seeds are able to germinate when they are provided with continuous light and plentiful nutrients, if these conditions do not occur, the seed coat continues to protect the seed and no growth occurs.

After a few days, the radicle (otherwise known as the embryonic root) emerges. This is followed by the seedling becoming visible from the soil. The seedling usually has two seed leaves called cotyledons which are a food source. Also, the embryonic stem or hypocotyl can be seen.

Between four and five days, the cotyledons grow larger.

At around day seven, true leaves begin to grow to about the size of 0.6 cm and so the plant is able to do photosynthesis rather than the cotyledons providing food, while the cotyledons begin to whither. The plant is roughly 1.5 cm in height.

At about day nine, flower buds begin to grow at the very tips of the plant.

Between days ten and eleven, the stem grows longer until it is roughly 10.2 cm in height. In addition, the buds and true leaves grow larger too, in an attempt to increase the photosynthesis to allow the plant to grow further still.

After thirteen to seventeen days, the plant properly flowers, producing clusters of small yellow flowers with four petals. The reproductive organs of the plant are visible, since the buds open. The true leaves are roughly 2.3 cm in length while the stem is about 13.3 cm.

Between days eighteen and twenty-two, the plant grows no taller and stops at roughly 18.6 cm. Also, the petals fall from the flowers, which have by this time been pollinated. Seed pods have developed and continue to grow until the seeds within are ripe, e.g. to a length of 5.5 cm. The true leaves, which ceased growing at a length of around 2.7 cm, go yellow to ensure that energy is being used for the growth of the seeds.

Bibliography

Articles

Kenrick et al (1997), The origin and early evolution of plants on land.

Wiley-Blackwell (2009), How did flowering plants evolve to dominate Earth?, ScienceDaily.

Books

Indra et al (2010), Plant Cell and Tissue Culture, Springer.

Jensen (1970), The Plant Cell, 2nd edition, Fundamentals of Botany Series, Wadsworth Publishing.

Mauseth (2008), Botany: an introduction to plant biology, 4th edition, Jones and Bartlett.

Oxford Dictionary of Biology (2008), Sixth Edition, Oxford University Press.

Purves et al (2004), Life the Science of Biology, Seventh Edition.

Ridge (2002), Plants, Oxford University Press.

Schmidt and Bancroft (2010), Genetics and Genomics of the Brassicaceae (Plant Genetics and Genomics: Crops and Models), 1st edition, Springer.

Journals

Diwani and Hawash (2009), Development and Evaluation of Biodiesel Fuel and By-Products From Jatropha Fuel, Egypt National Research Center.

Gasol et al (2007), Life Cycle Assessment of a Brassica carinata Bioenergy Cropping System in Southern Europe, Science Direct.

Greenway and Hader (2007), Variation in Ovule and Seed Size and Associated Size-Number Trade-Offs in Angiosperms, American Journal of Botany.

Gryzwacz et al (2010), Current Control Methods for Diamondback Moth and Other Brassica Insect Pests and the Prospects for Improved Management with Lepidopteran-Resistant Bt

Vegetable Brassicas in Asia and Africa, Science Direct.

Hayteer and Creswell (2006), The Influence of Pollinator Abundance on the Dynamics and

Efficiency of Pollination in Agricultural Brassica napus: Implications for Landscape-Scale Gene Dispersal, Journal of Applied Ecology.

Jeuffroy and Chabanet (1994), A Model to Predict Seed Number Per Pod from Early Pod Growth Rate in Pea (Pisum sativium), Oxford Journals.

Leishman et al (2000), The Evolutionary Ecology of Seed Size, CAB International.

Martinez et al (2010), Life Cycle Assessment for Joint Production of Biodiesel and Bioethanol from African Palm, Volume 21, Industrial University of Santander.

Pessel et al (2006), Persistence of Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.) Outside of Cultivated Fields, Theor Appl Genet.

Reports

Diamond (2002), Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication, Nature Journal

Websites

BIOCORE, What is Lignocellulosic Biomass, http://www.bioline.org.br/pdf?st09024 http://www.biocoreeurope.org/page.php?optim=what-is-lignocellulosic-biomass--

Biology Online (2005), Allotetraploid, http://www.biology-online.org/dictionary/Allotetraploid

IITA (2009), Cassava, http://old.iita.org/cms/details/cassava_project_details.aspx?zoneid=63&articleid=267

Ohio State University, Plant Cellular and Molecular Biology http://www.biosci.ohio-state.edu/~plantbio/osu_pcmb/pcmb_lab_resources/pcmb101_activities/stmsRtsLvs/stms_rts_lvs_root_tip.htm