- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Europe

British History: The English Civil War

Englishman vs Englishman

The King That Lost His Head

Background

Since the 13th century, the English monarch had needed Parliament’s approval to raise taxes; its increasing influence however, had greatly infuriated the Stuart kings. In reality though, the true causes of the Civil War can be traced back to when the pope refused Tudor king Henry VIII a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Henry rejected the pope’s authority and declared himself head of the Church of England in 1534. The Reformation that followed was consolidated during Elizabeth I’s reign by legislation making Protestantism England’s national religion. Since she was childless, she was succeeded in 1603 by her Stuart cousin, James VI of Scotland.

James’ belief in the Divine Right of Kings (that the king was god’s representative on Earth with unlimited authority) antagonised Parliament. He quarrelled with them over taxes and religious laws. Relations between James’ son Charles I and Parliament disintegrated further, exacerbated by his anti-Puritan policies. By 1629 he had dismissed Parliament three times, governing alone during the ‘Eleven Years Tyranny’ (1629-1640). He enforced royal authority through the Courts instead and raised money by selling titles.

England's Revolution

Declaration Of War

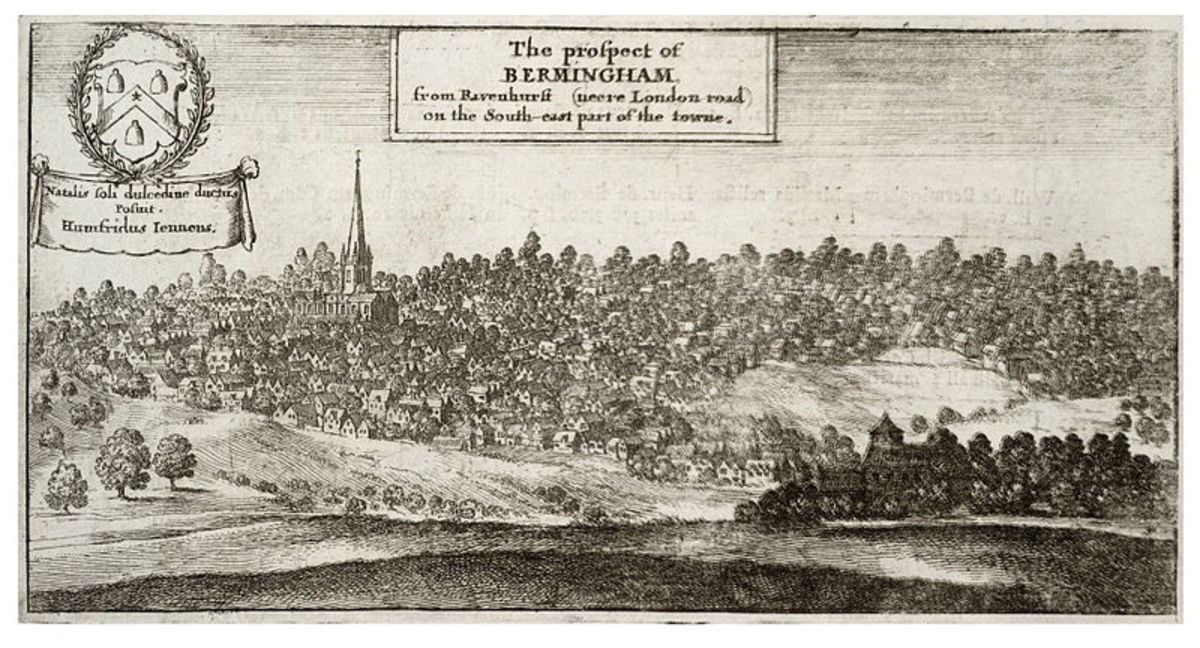

On the 22nd August 1642, Charles I raised his battle standard at Nottingham, signalling the start of the civil war that split England down the middle, pitting brother against brother and father against son. By the time it was over, around 10 per cent of Britain’s population were dead.

This war was not just the product of a quarrel between Parliament and the king. Religion also played a key role, as for many Parliamentarians, Catholicism and tyranny were inseparable. In 1640 Charles had recalled Parliament in order to raise money to quell a revolt in Calvinist Scotland against his clumsy attempts to impose ‘popish’ reforms, such as the Anglican prayer-book, upon them. However, instead of granting him cash, they countered with their own catalogue of recriminations, fuelled by 11 years of grievances. He was forced to dismantle the institutions of absolute rule and lost his right to dissolve Parliament. Rumours of his complicity in an Irish rebellion against Protestant English rule increased the tension. When news reached Charles that Parliament intended to impeach (charge with improper conduct) his Catholic queen, Henrietta Maria, he took drastic action. In January 1642, he entered the House of Commons with an armed force, intending to arrest five leading radical MP’s for high treason. Forewarned, they took refuge in the City of London, which considered Charles’ actions an outrage. Fearing for his safety, Charles went north to raise an army, while his queen went abroad to raise funds to pay for it.

The New Model Army

Naseby: The Birth of British Democracy

The Years Of Conflict

While the king commanded the loyalty of Wales, the west, and the north, Parliament controlled London, the east, and the south. The initial battles were inconclusive- a draw at Edgehill was followed by victories for the Royalists or Cavaliers, at Landsdown and Adwalton Moor in 1643, and for the Parliamentarians or Roundheads, at Turnham Green and Newbury. Numerical superiority and Scottish involvement led to Roundhead victories at Marston Moor in 1644 and at Naseby and Langport in 1645. After the fall of Oxford in 1646, Charles’ surrender to the Scots at Newark marked the end of the first civil war.

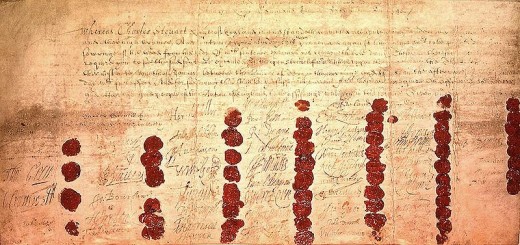

Parliament’s supporters now split into those wanted to share power with the king, and a more radical group, supported by the army generals, that wanted a republic. Despite his confinement, Charles continued to bargain with various parties, finally making a deal with the Scots to adopt Presbyterianism (their system of church government) in England in return for their support. The royalists rose again in July 1648 and the Scots invaded England. The New Model Army easily suppressed these uprisings before crushing the Scots at Preston. They then marched on Parliament and dismissed most of its members. The 58 who remained- known as the Rump Parliament- were ordered to set up a High Court to try the king for treason. Charles I was found guilty and beheaded on the 30th January 1649. This was truly revolutionary- monarchs had been deposed or killed before, but never legally executed. Parliament now abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords, declaring England a republic or ‘Commonwealth.’

The King's Death Warrant

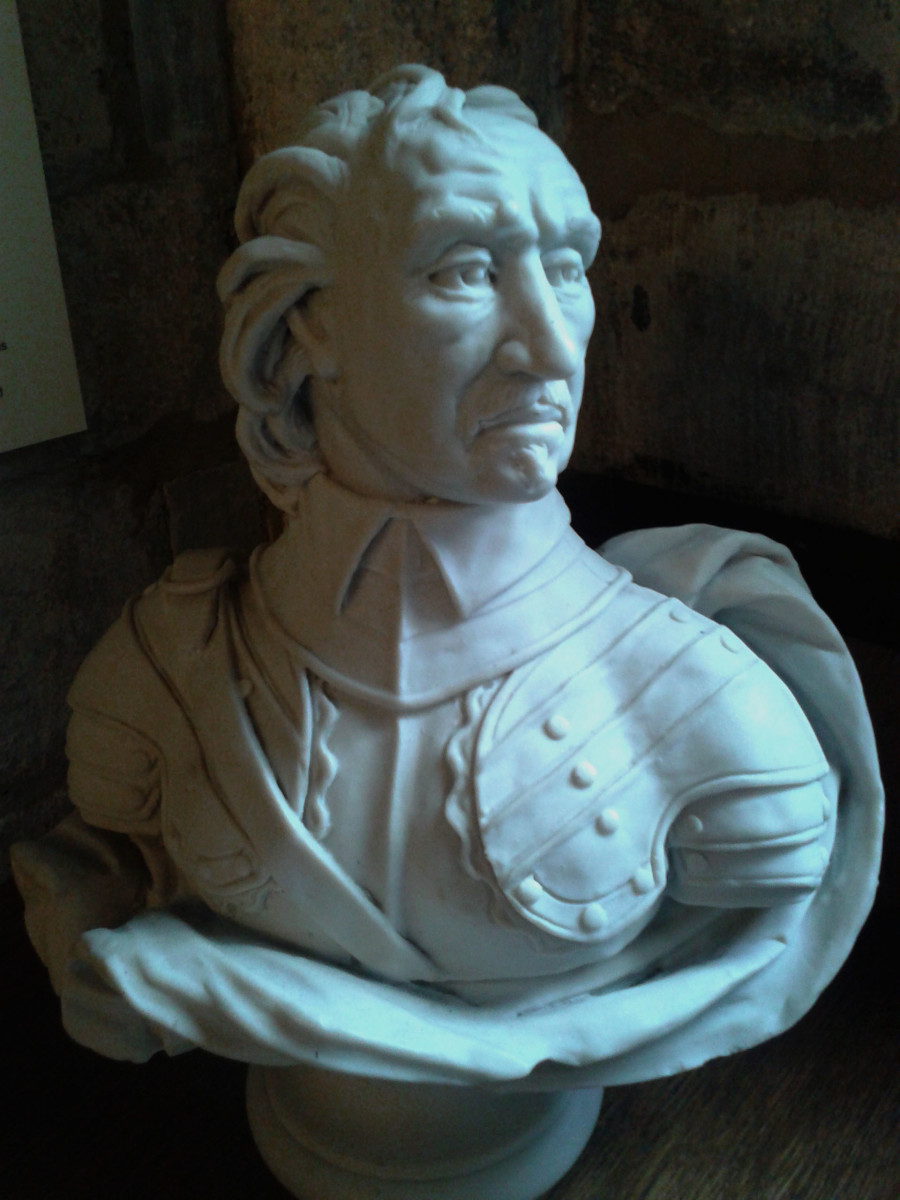

Oliver Cromwell

The Lord Protector

Before the civil war, Oliver Cromwell was a landowner and Puritan Member of Parliament. By the war’s end, he was Parliament’s most powerful military leader. He spent the next two years campaigning in Scotland and Ireland, crushing local uprisings and bringing them firmly under English control. His defeat of a Scottish army loyal to Charles I’s son (later Charles II) at Worcester in 1651 finally brought an end to the civil war. In 1653, Cromwell dismissed the Rump Parliament, unhappy at its failure to pass any reforms. After being appointed Lord Protector for life- a role that effectively made him a military dictator- he divided England and Wales into 10 districts ruled by army generals. His rule, based on strict Puritan principles, included the banning of most public entertainments, including Christmas. In September 1658, Cromwell died and was succeeded by his son Richard. With no powerbase, he was helpless against the army generals and resigned after less than a year.

Aftermath

After the resignation of Richard Cromwell, the vacant throne was offered to Charles II on condition that he supported religious toleration and pardoned those who had fought against his father. Puritan rules were swiftly dropped- theatres and music halls reopened, and public festivals, such as Christmas were restored. Nell Gwyn, a former orange-seller turned actress, became the most famous woman of the period, proving to be the king’s most popular mistress.

One of the more interesting characters to emerge from the civil war was Thomas Hobbes, who quickly became one of England’s most influential political thinkers. He lived through the bloodshed and his experiences form the basis of the views expressed in his book Leviathan, published in 1651, in which he advocates a strong government at the expense of personal freedom, arguing that mankind’s natural state is one of unending conflict.

In 1685 Charles II was succeeded by the openly Catholic James II, who quickly alienated his subjects by placing religion above politics. His advisers secretly invited the Dutch Protestant prince, William of Orange to take over the throne in 1688, in what became known as the Glorious Revolution.

© 2013 James Kenny