Catherine Howard

The Fifth Wife

Catherine Howard was the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard, the third son of the second Duke of Norfolk, and Jocasta Culpepper. The date of Catherine's birth is unknown, but it is supposed that she was born in the early 1520s. Catherine's cousin was in fact Anne Boleyn, as Anne's mother and Catherine's father were siblings.

After her mother's death in Catherine's early childhood, Catherine was sent to live with her step-grandmother, Agnes, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk. Catherine's father died in 1539, before Catherine was sent to the English court.

Her first relationship was with Henry Manox, her music teacher, when she was around eleven or twelve years old. Manox and Catherine did not fully consummate the relationship, though there was certainly some form of physical closeness as Manox would later confess to having 'felt more than was convenient'.

The second relationship was with Francis Dereham. This relationship was certainly consummated, and Dereham became Catherine's first lover. However, the relationship appears to have ended when Dereham went to Ireland and Catherine moved closer to the Court.

Catherine became one of the maids-in-waiting to Queen Anne of Cleves when the latter came from her home country to marry King Henry.

What did Henry see when he met Catherine? He saw a young female who was described as being a 'moderate beauty', and 'small and slender' with 'grace' and a 'delightful' countenance.

The image that has been identified as Catherine Howard is that of a miniature by Hans Holbein the Younger. Catherine, like her cousin Anne, wore the French hood, and was fond of jewels. Her hair is dark in the painting, and she has the Howard family nose. Whatever Catherine looked like, Henry was determined to make her his wife.

She retired from the Court, to Lambeth, when Henry set the divorce process in motion. He visited Catherine daily and was seen crossing the river in a barge. The Londoners took this to mean that the King was committing adultery, and didn't realise that Henry was intending to marry Catherine.

The King's marriage to Anne of Cleves was annulled on the 12th of July 1540. On the 28th of that month, King Henry married Catherine at Oatlands Palace. Thomas Cromwell, who had done so much to promote the Cleves marriage, was executed that day. Catherine appeared for the first time as Queen on 8th of August at Hampton Court. At the end of the month, the King and Queen went to Grafton where the King's maternal grandparents, Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, had married years before. After Grafton, they moved on to Amtphill, The More and Windsor.

Joan Bulmer, one of the ladies who had been at Lambeth and Horsham with Catherine before she married the King, wrote a letter to her with a subtle reminder that she knew about Catherine's past history with Dereham. Catherine took the hint, and had Joan brought to Court to be one of her ladies. Catherine's ladies included her cousin Mary Howard, Duchess of Richmond, Lady Margaret Douglas, the King's niece, Lady Arundel, Countess of Sussex and Lady Denny, wife of Sir Anthony Denny. The most important of the Queen's ladies was Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, who was Chief of the Privy Chamber. It was Jane who testified against her husband George and his sister Queen Anne Boleyn in 1536, and whose testimony helped the siblings to the scaffold. The Dowager Duchess of Norfolk pressed Catherine to accept Francis Dereham into her household; the Queen gave him a position as she said, 'My lady of Norfolk hath desired me to be good unto him, and so I will.'

Queen Catherine was fond of her stepdaughter and cousin Lady Elizabeth, occasionally giving her trinkets. However, she and her other stepdaughter, Lady Mary, did not get along. Lady Mary was older than her latest stepmother, and she looked down at her as a silly and vain girl, who wore new dresses every day. Queen Catherine wanted the same respect that Lady Mary had given Anne of Cleves, so as punishment for not showing respect, Catherine had two of Lady Mary's maids taken from her.

The King and Queen spent Christmas of 1540 at Hampton Court. The King gave Queen Catherine many gifts, including a pendant with 27 diamonds and 26 pearl clusters. Anne of Cleves paid a visit after New Year, and appeared to get on well with the King and Queen.

In February, Henry went to London for three days to deal with business. It was the first time that the King and Queen had been apart since they married the previous July. When the King returned from London, the wound on his leg that had troubled him for years after a jousting accident, became worse. The King, in his agony, shut himself up in his rooms and refused to see the Queen. Rumours began to circulate that the King had tired of Catherine and intended to get rid of her. However, the King recovered and he proved the rumours false by reuniting with his wife.

An attendant during the King's illness was a distant cousin of the Queen's, a man named Thomas Culpeper. He was attractive to women and high in the King's favour. However, this popular young man did have a very dark side. In 1539, Culpeper attacked the wife of a park-keeper whilst others held her down. When someone tried to rescue the woman, he was murdered. The King himself pardoned Culpeper.

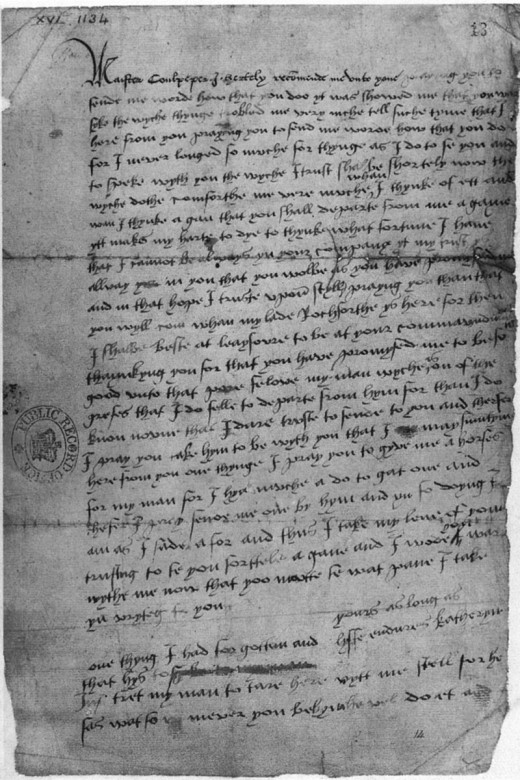

In April 1541, according to Culpeper, the Queen summoned him to her presence chamber. Catherine gave him a velvet cap with a jewelled brooch and told him that if she had 'tarried still in the maidens' chamber', then she 'would have tried' him. When he became ill, the Queen wrote him a letter, begging him to let her know how he was, and ending the letter with 'Yours as long as life endures, Katheryn'. It is the only surviving letter written by Queen Catherine, and Culpeper, for whatever reason, kept it.

On the 28th of May, the King ordered the death of Lady Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury. Lady Salisbury was the cousin of Henry's late mother, Queen Elizabeth of York. In previous years, Henry had looked up to Lady Salisbury, but during the 'Great Matter', Lady Salisbury took Katherine of Aragon's side, and the King never forgave her for it. During her imprisonment, Queen Catherine showed a thoughtful side, and sent her clothing lined with fur to keep her warm. However, Lady Salisbury was butchered at the block at the age of 68.

The King and Queen set out on their Progress in the summer of 1541. They stopped at every town on their way as people greeted them. The journey was slow and the rain was heavy, making travelling on muddy roads difficult. They travelled through Dunstable, Ampthill, Grafton, Northampton, Stamford, Lincoln and Boston. After leaving Boston, they travelled through Northumberland and on to Newcastle, the furthest north that the King had ever travelled. After this they headed south to Pontefract.

In September they moved to York, to await James V, King of the Scots, Henry's nephew by his elder sister Margaret. Henry and Catherine waited for several days, but the King of Scots did not turn up, and eventually they gave up and went to Hull. After this they travelled south through Kettleby, Collyweston and Ampthill before reaching Windsor near the end of October. The King learned that his sister Margaret had died, and also that the young Prince Edward was ill, though to the King's relief, Prince Edward improved.

On 1st November, King Henry ordered that all churches should give special prayers for his Queen as 'that after so many strange accidents that have befallen my marriages' God had been 'pleased to give me a wife so entirely confirmed to my inclinations as her I now have'. His happiness would be short-lived.

Whilst the Court was on progress, a man had approached the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. His name was John Lascelles, and his sister Mary had been one of the maidens at Lambeth with Catherine before her marriage. When Lascelles pressed his sister to ask the Queen for a position, Mary had refused, and explained what had happened in the past with Manox and Dereham. Lascelles told the Archbishop about the Queen's past and had apparently carried the burden for a year, but had reasoned that keeping it secret would make it worse.

One can almost pity King Henry when Archbishop Cranmer slipped into the Royal pew and left a letter there for Henry to read. Cranmer had been too afraid to tell the King in person because Henry loved Catherine.

The King read the letter in disbelief. He did not believe a single word of it to be true, and ordered an investigation so that Queen Catherine's name would be cleared. He decided that he would not see the Queen again until the issue was resolved. Henry never saw her again.

Manox and Dereham were both taken to the Tower of London for questioning. Manox insisted that he had never slept with Catherine, though he admitted that they had been close. Dereham had replaced him in her affections.

The King was informed on the 5th November that the allegations of the Queen's lovers before marriage appeared to be true. King Henry VIII could not speak, and broke down in tears before his Privy Council.

Cranmer visited Queen Catherine on the 6th and 7th of November, hoping that he could get a confession from her. He also helped her write a letter to the King, making a 'confession of my faults' and that she was 'so blinded with the desire of worldly glory, that I could not, nor had grace, to consider how great a fault it was to conceal my former faults from your Majesty...'. The King was more inclined to show the Queen mercy and became a little more cheerful.

The fall of Queen Catherine was kept quiet, but people realised something was wrong. The French ambassador Marillac noted that the Privy Council looked 'very troubled, especially Norfolk'. The Duke of Norfolk had every reason to be troubled. Only five years before his niece Anne Boleyn had been Queen and executed on the King's orders. Now Catherine might create another scandal that could threaten the Howards.

Francis Dereham was tortured in the Tower, and he revealed that Thomas Culpeper was Catherine's favourite. Culpeper found himself in the Tower as well, and his possessions taken. The letter from the Queen to Culpeper was found, and it did not bode well. The Queen's ladies testified that at various places on the progress that year, the Queen had forbidden them to enter her bedchamber. On another occasion, the King came unexpectedly to the Queen's bedchamber and found that the door had been bolted. There was some delay before Lady Rochford admitted the King. One of the ladies also named Lady Rochford as assisting the Queen.

Now it was Lady Rochford's turn for questioning. At first she protested her innocence, but upon seeing that it was getting her nowhere, she revealed everything about Queen Catherine and Culpeper in the hope that she could save her own skin. It didn't work, and Lady Rochford was sent to the Tower, where she apparently went mad.

Culpeper himself was tortured and in his agony refused to admit to having sex with the Queen, only that he 'intended and meant to do ill with the Queen and that in likewise the Queen so minded to do with him'. The King was so furious and distressed to discover her affair with Culpeper that he called for a sword to slay Catherine.

Queen Catherine had been moved to Syon Abbey on the 13th November. Archbishop Cranmer had been pressing her to admit to a pre-contract between her and Dereham. It would invalidate her marriage to the King, and it might have saved her life. However, either through her Howard pride or sheer stupidity, she failed to grasp this. She only saw that it would mean that she had never been the Queen, and she refused to sign a paper to that effect. On the 22nd November, she was stripped of the title of Queen. The King and his ministers were probably very relieved that she was not pregnant as it could have jeopardised the succession with an illegitimate child being passed off as the King's own.

In the meantime, there was a rumour that Anne of Cleves had borne a son by the King. A full enquiry was launched and it was discovered that two members of the Lady Anne's household had slandered her.

On 10th December, Francis Dereham and Thomas Culpeper were executed. Although Culpeper had committed treason by adultery with the Queen, he was only beheaded, perhaps as a result of his gentleman status and some dregs of fondness that Henry had felt for him. Dereham was not so lucky. He was not a gentleman and the King looked upon him as the man who spoiled Catherine. Dereham was disembowelled and castrated before he was beheaded.

The Howard family also found themselves in the Tower at the risk of being dragged down with Catherine. The Duke of Norfolk wrote a pleading letter to the King and referred to the 'most abominable deeds done by two of my nieces'. Norfolk escaped whilst the rest of his family languished in the Tower.

A delegation arrived at Syon on the 10th of February 1542 and told her that she was to go to the Tower. Catherine broke down and had to be helped on to the barge waiting to take her. She would not have the chance to defend herself. An Act of Attainder was passed against her on the 11th of February , meaning that she could be executed without trial. At the Tower, she was told that she was going to die. She asked for the block to be brought into her room so that she could practise putting her head upon it.

The following morning, Monday 13th February 1542, Catherine was brought to the scaffold on Tower Green, so weak that she could hardly stand. In her final speech she admitted that she deserved 'worthy and just punishment' and asked everyone to pray for her husband. Her head was struck off by an axe. Lady Rochford then followed her, being executed after recovering her wits long enough to make a speech.

It would be over another year before King Henry VIII took the plunge and married his sixth wife. He thought that Catherine was his 'rose without a thorn', but he had been wrong. She was the last woman that King Henry ever really loved, and from that time on he was an old man, needing a nurse more than a wife. Her death also had an effect on her stepdaughter, Lady Elizabeth, who declared that she would never marry.

The body of Catherine Howard was buried the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula, near her cousin Anne Boleyn. The Act of Attainder against Catherine was reversed by Queen Mary I in 1553 because it did not bear Henry's signature, and was considered invalid. Now, her burial place is marked by a small slab that reads 'Queen Catherine Howard. MDXLII.'