Classified Material

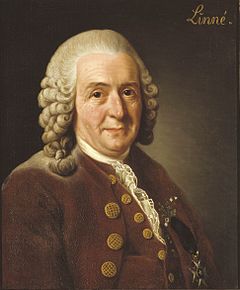

Carolus Linnaeus smiles his ethereal smile. Perched above the layered clusters of viridian, awl-like foliage atop the Araucaria heterophylla, he gazes lovingly beyond his invisible feet, tracing the pattern of spreading branches spiralling downwards towards the ground fifty feet below. Clustered foliage, upraised in supplication to the sun, reaches into the air, drawing sustenance from the unseen. Next to the tree is an old red-brick gardeners’ cottage, now used as offices by Botanical Administration. Acres of carefully tended specimens unfurl around Linnaeus; thousands and thousands of trees, shrubs, herbs, flowers and grasses—seemingly from every country on earth—drawn to him, drawn to his vision. Arboretums, beds, herbaceous borders, parterres, hothouses, ponds and artificial lakes—all a-jostle with botanical beauty; truly a Kingdom Plantae with a place for every plant, and every plant naturally in its place. And, joy of joys, the old naturalist’s eyes mist over, at the base of every specimen is an identification plaque showing Family, Genus, Species and common name where applicable—this is his legacy, the fruit of his eighteenth century imaginings.

A few yards from the Araucaria stands an imposing multi-storied edifice—the Herbarium. He drifts through its beige masonry walls and into a vast climate-controlled space, filled row after row, floor to ceiling with powder-coated, multi-shelved metal cabinets. Each shelf harbours a substantial stack of large, meticulously filed folders. Each folder is host to a similarly sized piece of rectangular white cardboard. Each piece of white cardboard bears an assemblage of physiologically inert, dried and preserved plant material, together with a precise and standardised scientific citation. Each piece of plant material is secured—sometimes by glueing, sometimes by paper-taping or sewing it onto the white cardboard (or using a two or perhaps all three of these techniques in combination—this depending upon the size, shape, contour, irregularity, fragility, elasticity and other pertinent physical characteristics informing the readiness with which each particular sample is willing to comply with being so transfixed). Each plant specimen is positioned so that, as far as possible, taxonomically important features such as flowers, seeds and fruits are near the edges to allow botanists more easily to examine them through their microscopes.

Fragments and scraps—seeds, foliage, twigs, fruit—no matter how small are carefully placed in small transparent bags which, in turn, are concealed in folded paper pockets or envelopes glued to the cardboard mounting board. These pockets are always positioned to ensure minimum disturbance of the featured plant. A paper fragment pocket with its plastic liner bag is companion to every mounted specimen—even when, initially, there are no scraps to be stored, there is always the possibility of fragments being created during future scientific investigations or by chance damage.

There must always also be room on the mounting surface for the labels. An identification label provides information about the plant’s name, genus and family; who collected it and when and where; locality description; and, other pertinent details. Perhaps other labels will be affixed in future years by botanists either in agreement or disagreement with the specimen’s original taxonomic ascription.

Each specimen stored in blackness.

Databased, catalogued, labelled, filed away precisely.

The old man is in the heaven of his dreams.

And then there are the non-seed-bearing lichens, mosses, fungi and algae; not suited to mounting boards, but stored in small packets, preserved in spirit or encased in microscope slides; but ever databased, catalogued, labelled, filed away precisely.

The old man sees his dreams have come true.

And he knows that all over the planet are similar great collections of living and dead plants. And that these collections communicated with each other and exchanged plants and information with each other, often at the speed of light, the speed of thought. So that in reality, the earth is dotted and criss-crossed by his ideals, a gigantic and ever-growing ordered distillation of the botanical realm. Forever being defined and redefined, databased, catalogued, labelled, filed away precisely. An ever-spiralling process, an expanding maelstrom of empirically-based classifications metabolising nature.

Each specimen a hidden work of art, proof of scientific primacy, a source of bliss, of ordered delight, of empirical ecstasy for all rational beings. Linnaeus smiles. Science has the power to tame the wilderness. His contribution has been to name nature’s offspring, so that what is named is isolated, examined and assigned properties drawn from techne’s numerous domains—physical, chemical, genetic, botanical, aromatic, medicinal, anthropological. These properties provide a matrix determining which species are useful and which are to be eradicated. Creation reshaped to humanity’s plan. Wilderness tamed. For the benefit of all.

Civilisation from wilderness?

Wilderness from civilisation?

I create the space, the spaces wherein I dwell. You create those in which you dwell. We create together the space, the spaces where we all live. The world’s definings. The spaces of civilisation, culture and society; urban, suburban and rural spaces; the heavens, the countryside, the seascapes, woodlands, grasslands, jungles, deserts, tundras. The bounty within and the harvest without. The wilderness within and the wilderness beyond. Wilderness as a state of soul. Transforming through thought, spirit and circumstance.

How does wilderness vanish? Is our wild birthright sold in return for civilisation’s veneer? Is the natural state unnatural for human beings? The noble savage transformed into common consumer? But before wilderness ends, it has to exist. So when did wilderness begin? Where does wilderness begin? Within us? When nature is tamed, when nature is constrained, so are we.

© John Hopper