Cognition the Visual Perception

Ambiguous Figures Experiment

- You are walking down the road enjoying the wonder of the warm fall day in your community. The world is so quiet you can almost hear yourself breathe. You stop to take in the beauty of the mountains to the west, when suddenly a small dog rounds the corner in front of you, barking and racing towards you. Are you scared? Do you feel threatened by this mighty bark attached to this micro dog? Chances are that each of you reading this will have slightly different responses.

- Perception is how we interpret information in the outside worlds that enters via our senses. Perception is dependent upon our past experiences, the context we are in when the stimulus arrives, and frequently, our mood state. Therefore, how you perceive something today may be very different from how you perceive the same stimulus tomorrow.

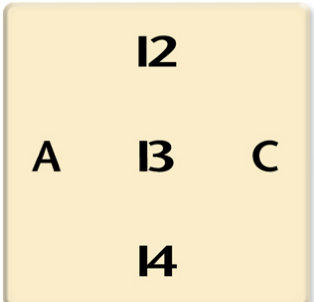

- Ambiguous figures provide a dramatic illustration of the influence our experiences, beliefs, and expectations can exert on perception. Ambiguous figures are stimuli that can be interpreted in more than one way. For instance, the figure in the picture to our left can either be seen as a "B" or as the number "13." Whether you see it as a "B" or a "13" is dependent upon your own experiences, but it can also be guided by the context in which you observe the stimulus. In one case, you are more likely to see it as a "B" if we surround the ambiguous stimulus with other letters, whereas, you are most likely to see it as "13" if we surround it with numbers (Chambers, 1992). Therefore, perception may be altered by the context in which the stimulus is introduced.

- In this experiment you will participate in 14 trials in which you will be asked to identify what you see in an ambiguous figure. Each trial will begin with the presentation of several pictures, followed by the test ambiguous figure. Once the ambiguous figure is presented, you will be asked to choose between several options to describe what you see.

- In this experiment you were presented with pictures that were intended to "prime" you into viewing the ambiguous figure in a particular way. For instance, in the ambiguous figure that could be perceived as a duck or a rabbit, you were primed with pictures that clearly fell into only one of those interpretations.

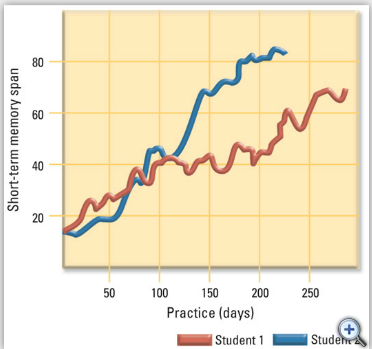

- What we measured in this experiment was whether or not you perceived the picture in a way that matched the prime. The first graph you will see when you click on "View Global Results" shows you how often you interpreted the picture as the same object as you had been presented during the priming. If your "Percent of Primed Answers" score was above fifty percent you were very likely affected by the priming condition.

- However, remember that you saw each ambiguous figure twice and it may be that once you are primed to see an image a certain way it is difficult to see the image differently, even if you are given new primes. The second graph you see when you click on "View Global Results" divides your results into two sets: how often your perception matched the first set of primes ("First Viewing") and how often your perception matched the second set of primes ("Second Viewing").

- If the second set of primes were just as effective as the first, then the percentage of time your perception matches the primes would be the same for both the First Viewing and Second Viewing. However, if the first set of primes created a lasting predisposition to view the images a specific way, then the percentage of times your perception matched the primes for the Second Viewing should be lower than the percentage of times they matched for the First Viewing

- Perceptual scientists call the way we are primed to see things in a particular way our "perceptual set". Some of the aspects of our perceptual set are short-lived, such as when we prime you to see a "B" or "13" by surrounding the stimulus by a group of unambiguous stimuli.

- The presentation of ambiguous stimuli requires that you use a process called top-down processing. Top-down processing is a cognitive process that occurs when the conditions surrounding a stimulus are unclear. Top-down processes become involved when a stimulus is vague and we are forced into using context cues, prior experience, and expectations to analyze the stimulus. When exposed to situations that are completely clear, we use bottom-up processing. Bottom-up processing is based on making a detailed analysis of stimulus information, as you are doing when you read these words on this screen.

- One way to think of top-down or bottom-up processing is to think of yourself when trying to solve a jigsaw puzzle. If you were given a jigsaw puzzle without the original box or picture of the final product, you would have to use bottom-up processing. You would simply have to rely on color and shape to solve the puzzle. However, if you have a picture of the final product you are able to use top-down processing. For instance, if you know the upper left hand corner has a red barn on it, you can go through all of the pieces and pick out what pieces you think are part of the red barn. It makes constructing the puzzle quicker and easier because you know what to expect. As you might predict, top-down processes require activation in more complex areas of the brain and more overall brain areas than bottom-up processing (see Kommeier, 2004; Nyberg, 2002 for discussion).

References

Chambers, D. & Reisberg, D. (1992) What an image depicts depends on what an image means. Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 24)2), pp. 145-174.

Davis, J. (1994). Why do ambiguous figures reverse? Acta Psychologica, Vol. 87(1), p. 33-57.

Gopnik, A., & Rosati, A. (2001). Duck or rabbit? Reversing ambiguous figures and understanding ambiguous representations. Developmental Science, Vol. 4(2), pp. 175-183.

Kornmeier, J., & Bach, M. (2004). Early neural activity in Necker-cube reversal: Evidence for low-level processing of a gestalt phenomenon. Psychophysiology, Vol. 41(1), pp. 1-8.

Nyberg, L. (2002). Levels of processing: A view from functional brain imaging. Memory, Vol. 10(5-6), pp. 345-348.

Rock, I., Hall, S., & Davis, J. (1994). Why do ambiguous figures reverse? Acta Psychologica, Vol. 87(1), pp. 33-57.

Verstijnen, I.M. & Wagemans, J. (2004). Ambiguous figures: living versus nonliving objects. Perception, Vol. 33(5), p. 531-546.

How do your experiment results relate to what you have learned in this module? What insights did you gain about cognitive processes and associated research methods by participating in this experiment?

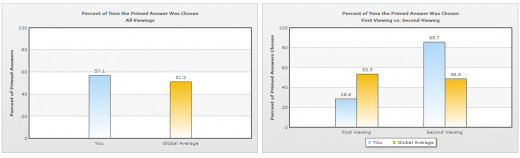

I completed the Ambiguous Figures experiment in My Psych Lab and found it to be interesting. During my first viewing I chose the primed image 28.6% of the time which is 24.9% less than the global average. During my second viewing I chose the primed image 85.7% of the time which is 36.8% more than the global average. I believe my selection of the primed image increased during the second viewing because during the second viewing of the images I paid more attention to the images that came before the test image.

In relation to this week’s module I found Gestalt principles applied to the experiment. In particular I found the Gestalt principle of similarity caused me to separate the images into one picture due to color. For instance I saw a skull no matter if the image was primed or not because I separated the image into white and black making the only image I saw was the skull. I also realized how difficult it is to stop my eyes from making fixations and saccades even when I was consciously attempting to avoid them; my perception of the images was partly influenced by my failure to stop my eyes from pausing to take in visual information. The Ambiguous Figures experiment has lead me to believe that many “magicians” study how cognitive processes work and how to make use of the Gestalt principles as well as our visual saccades and fixations instead of any type of magic. Many magicians use the Gestalt principles to control what people fixate on thus controlling what they observe in order to create the perception that magic was produced.

1: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: An old man (Primed Image)

2: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: Skull

3: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: Old man

4: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: An Eskimo

5: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: A young lady looking away

6: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: Duck

7: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: An old man

8: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: A skull (Primed Image)

9: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: A lady's face (Primed Image)

10: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: Eskimo (Primed Image)

11: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: A young lady looking away (Primed Image)

12: Which of the following best describes the image you last saw?

Your answer: Duck (Primed Image)

References

Pearson. (2014) “Can What You See Be Changed by what’s Around You? Simulate the Experiment: Ambiguous Figures. Simulations. Retrieved From: http://digitalvellum.next.ecollege.com/postindexmixed.html?courseId=10187590#/menus/5000007631830/items/2000015045191

The Psychology of Music: Steven Demorest and Professor Morrison

The Psychology of Music: Steven Demorest and Professor Morrison

"1. How did you become interested in the psychology of music?

>> Well, music education has been an interest of mine since I was an undergraduate. I started out as a choir director teaching in the secondary level and then later at the college level, but when I went back for my PhD, I got very interested in research and spent a fair amount of time looking into psychological research, both in education, but particularly in music. And so that led me to doing research in music psychology. And actually the field of music education has a long history of research in music psychology, educators being interested in music teaching and learning, music learning required that we know more about music and how it is processed.

>> I also started professionally as a music teacher. My background was more in instrumental music, so had been in orchestra musical playing, and as I went through graduate school, I developed an interest in, in studying how people developed musical skills, you know, how does, how does one come to be a skilled performer?

2. What is your current area of research?

>> Sure. We're -- we do research in, in roughly the same area at least for what we're here at this conference for, which is in cross cultural musical understanding. So comparing the responses of listeners from different cultures to music of different cultures, both in terms of their behavioral responses, how they do on a memory test or, or perception of intonation, or style, or things like that, and neurologically, what kinds of activation are associated with hearing culturally familiar music, versus culturally unfamiliar music.

>> When you look at music study now-a-days, all music is considered, it's not the traditional sort of conservatory study where folks are just studying the, the -- what's considered the traditional classics. So with all music being considered and performed and listened to, and, and artists from my different traditions coming in as, as teachers, one, one wants to investigate how does one interact with all these different kinds of music? Is there one kind of way of thinking about music? Or do all these different musics necessitate different, different points of view in, in psychological perspective?

3. What is the relation of language and music?

>> We, we started looking over the, the literature that is associated with language, there's a great deal of research that's been done on people's understanding of language that they know, versus language that they don't. While we didn't mean to equate music with language, we thought of it in somewhat analogous fashion, does an individual who spends time in a culture listening to a certain kind of music understand, if you will, that music better than a music that's perhaps new and completely unfamiliar to them. So that's the general idea from where we started.

4. What did your research find regarding music and the brain?

>> So we looked at this from two perspectives, the behavioral perspective, just like a straight cognitive psychology study was using memory performance of listeners of different ages and from different cultures, hearing music of their own culture and music of another culture. And in all cases, regardless of the age of the subject or the complexity of the music thus far, we have found what we call an enculturation effect, that is that people are significantly better at identifying between heard and unheard examples of music from their own culture, versus an unfamiliar culture. And one important element of those studies, all of the music that the subjects hear is novel, they've, they've -- it's not music that they've heard before, it's simply music that's from their culture, versus another culture's. So, we seem to have preferential memory structures for music that's culturally familiar, not too surprising, given that we were, we were raised in these cultures.

5. Have you found differences in neurological levels based on the types of music heard?

>> On the neurological level, the questions that we raised then were are there different neurological resources that are being used when people are dealing with their home music versus some other unfamiliar music. And generally speaking to this point, we've not found that there are any unique differences ascribed to one kind of music or another kind of music. There might be a difference of degree, but it seems that people are dealing with even very unfamiliar music as music and trying their best to make sense of it.

>> One of the ways that shows up, we often think of when we are looking at neuroimaging that we're looking for activation associated with something that you know. But in the case of hearing culturally unfamiliar music, we're beginning to find activation when you hear something you don't know, that is it's more work and that shows up as a stronger neurological response. Again, in the same areas or not, not that you're, you're using different resources, but that you're recruiting them at different levels depending on how difficult the stimulus is for you to process.

>> The challenge about music study as opposed to language study, one can give someone linguistic information and test them to see if they understood it just by saying, what does this mean. Music is much more covert process. One can say, oh, yeah, I think I understand that, when in fact they didn't at all, where they understood it in a way that was completely inappropriate for the kind of music they were hearing. So, the reason that we're looking into this process, particularly in terms of musical memory is trying to find some ways at seeing and observing that sort of difference in understanding.

6. Is there anything that surprised you in your research?

>> Yes, definitely. And perhaps it should not have as we began to look more closely at the literature, but we had predicted that our musically trained subjects would do better on the memory task than there are untrained subjects even in culturally unfamiliar music, as well as familiar music. And that was not the case at all. There was no difference either for western subjects or Turkish subjects based on the amount of musical training that they had. So, it would appear that the kind of musical expertise we were testing was actually the expertise developed as a member of a culture rather than through formal training.

>> Now, certainly music training has effect. One accrues a great deal of performance skill often. There's a lot of terminology, a lot of theoretical information, but what our result suggests and this goes along with other research that's been done, is that folks who have had minimal or even no formal musical training still have a very sophisticated level of musical knowledge. They can do some very impressive things interacting with music.

>> One of the reasons that's confusing to people is we often think of musical expertise in terms of what you might call your productive ability, how often you perform. And of course untrained folks aren't very good necessarily at performing, but what we're testing with musical memory and some other perceptual judgements is actually your receptive ability. And as a member of a culture, over years, you develop a pre-sophisticated system for encoding and retrieving musical information. You may not be able to perform it very well or be very creative with it, but you're really good at discerning and you know, you can go to any record store and look at all the different styles of music that are available to realize that everyone is really good at discerning different kinds of music and how it might affect them.

7. What did you find regarding differences in musical capabilities among individuals?

>> Well, talent is a challenging word, first of all, I think as a music educator. Not that we don't recognize that people have different levels of aptitude for music, but people have different levels of aptitude for language, for mathematics. But talent is a word that seems to be reserved for music and the cultural assumption in our culture behind that is that music is for the very few, that there are these very few people who are talented, who will benefit for musical study. In our experience both as researchers and educators is that everyone has musical capabilities, really, and the research would suggest from birth and all children benefit from musical study. They won't all become performers just as not everybody who studies language becomes a novelist or everyone who studies math becomes a mathematician, but that they can deepen their musical knowledge and appreciation and their performing ability through careful music study at any point in their lives.

>> As a matter of fact, if you look at any child, young children are doing musical things all the time. And if we look at musical things to include both sound making and movement that's associated with music, it's a big part of their young lives. That vanishes over time and perhaps we would suggest due to cultural forces rather than the fact that they actually lose any sort of skill. So, these sorts of results that we are getting help us support the idea that people actually do bring a lot of skill to musical interactions.

>> One of the unknowns is if we were to devote as much time to studying music as we do to learning language or learning mathematical skills, what kind of distribution of musical talent, if you will, would there be in the population. At present we don't have enough, you know, people don't have enough exposure formally to musical training for us to make that distinction and so there's--if talent becomes a self perpetuating notion that since fewer people are seen as talented, fewer people studying music, therefore, fewer people exhibit musical talent, it kind of, you know, as a chicken and egg problem, like catch-22. And so as music educators, one of the things that we really stress and as music researchers is looking at the musicality that all individuals in our society possess and how that musicality is expressed in various ways and how to best develop it in children.

8. Does music affect cognitive functioning or performance of unrelated skills?

>> I think the best place to begin is the idea of music that in our society we take a very specific definition of music. Certain things are music, and certain things are not music, and we look at brain function, music is not a very tightly compartmentalized process. Music demonstrates some unique patterns of brain activity but also demonstrates a lot of activity that's shared among other sorts of things. So to say that interacting with music as a listener, as a performer does not affect any other kind of thinking, so to speak, is probably, ultimately proved to be inaccurate. Now whether one can say that by doing music it makes you better at something else, I think we're a long way from saying that with any sort of certainty, and I would argue that that might not be the ultimate direction we would want to go because it would, it would seem that there are probably better ways at learning that other thing than doing music. Likewise, the value of music making itself seems to be a social imperative that's existed, that currently exists in every human society and has existed as long as history goes back.

9. The Mozart Effect indicates that listening to classical music can improve memory. Did your research support or debunk this theory?

>> You asked the question debunking, and nothing in our research actually deals specifically with the Mozart effect in that way. However, numerous researchers have tried to replicate this effect without much success. So there is, within the literature, a significant question about whether, whether or not this effect is real, and it's important to remember that the Mozart effect isn't about memory as a sort of global thing. It's spatial, temporal reasoning, and the effect was short term in terms of the number of questions on the test that students were out performing. So the effect itself was fairly narrow. That doesn't necessarily take away from its significance, but it was fairly narrow in application, and one of the things that hasn't really been explored is to what extent do a wide variety of musics, you know, potentially have a similar effect. It's been compared to other types of music, but without maybe as careful controls as you might have and certainly from a global perspective, we wouldn't want to assume that the only music with which it can interact is that of a 200-year-old Austrian composer, and everyone else's music doesn't have any impact on your cognitive function. I think that would be a problem.

10. How did you standardize your research across cultures, and how did you find familiar and unfamiliar music for these cultures?

>> Sure. Well, in the [Inaudible] that we've done, our task was to come up with a music that we called, Culturally Familiar, and another music called, Culturally Unfamiliar. One of the challenges was to come up with a music that stylistically was familiar but that people weren't familiar with the exact piece; so it wasn't a very famous piece. We picked out -- we tried to control music that didn't include vocal parts; so there were no lyrics to get, you know, muddy the mix. We tried to keep everything around the same tempo, around the same number of performers. Similar, but not the same instruments because each culture has its own unique sort of instrument structure. So the specific structural aspects was control as possible. The music we picked for Western music was classical music because it's very easy to find instrumental music in that area, and it's also very easy to find music that no one's ever heard in classical music. Likewise, and Turkish music, we used music from the Turkish classical tradition and the Chinese music from the Chinese classical traditions. So these were all very unfamiliar pieces to the listeners.

11. Does human musical behavior change or improve with the evolution of a population?

>> Well, this is a question that has become increasingly prominent, and it's beginning to be featured in music psychology textbooks, actually including a chapter on music and evolution. I don't think we have a lot of answers yet. One of the sort of surprising maybe disturbing things is that there have been theories of evolution that don't discuss human music making as a component. Darwin, however, did. So the initial theory of evolution did include musical behavior as a significant human activity. Whether music is an evolutionary adaptation or a cultural acceptation, or whether it is some sort of language artifact, is what some people like to believe. We don't really have the details on that. What we do know is that every known human culture has music, and those cultures didn't necessarily interact with each other to pass it on. So it seems to develop spontaneously as a part of human social behavior. And certainly, that, the research on influence has shown that they are predisposed to process music in ways that, you know, indicate adult understandings of aspects of things, like contour and key, in ways that other primates, at least as far as we know right now, can't. So there are some precursors of musical behaviors in primates but human musical behavior, much like human language, seems to distinguish us, and it does seem to be at least ubiquitous in human culture.

12. Can music be used to regulate mood?

>> We have not done research in that area, but there is a -- a -- a -- a healthy body of research looking at music and its effect on our state - our -- our emotional state. Sociologically speaking, we can look at young people and see that they use music expertly in that way. You know, it becomes kind of a soundtrack for certain aspects of their lives. There are certain tunes that go with certain -- certain life events and certain sorts of moods. Likewise, if people would like to get into a certain mood, often they'll pick out a particular favorite song, or a particular set of songs, and they'll -- they'll take that. You know, of course mood and -- and state is a very covert thing. We don't see that the -- the mood generated by a particular piece is the exact same state, but share it among a group of listeners. But there seems to be a strong imperative to use music in that way. Now to -- to build a bit further, there's a -- a -- an entire branch of a field that's devoted to employing music as a therapeutic agent, both in terms of state and in terms of physiological dysfunction [phonetic]. So it -- it has a -- it seems to have a tremendous amount of power in -- in the way that we interact with our environment. And while there -- there's agreement often in the sort of general emotional characteristics of music using sort of broad surface cues like tempo and -- and sometimes melodic direction, or even mode. The -- the choices of music for people to regulate their moods is often highly individual. And so even when they do study, it's like, you know, preoperative stress reduction and things like that. They can't say this music will work for everybody. Everyone has to bring in their own music. Now once -- once that's been done, it -- it does seem to -- to make a difference in the subjects. And I think mood regulation and emotional disturbance have been sort of the typical views of music therapy as a discipline, but -- but as Steve [phonetic] was mentioning, recent research in music therapy has moved into areas like neurologic music therapy, where you're actually using music to -- to affect biological conditions. For example, the work of Michael [inaudible] on using rhythm to regulate gait in Parkinson's patients, things like that. So -- so there -- the impact of therapy is -- includes mood regulation, but also seems to go well beyond it in looking at how music interacts with -- with our neural architecture.

13. What direction do you see your research heading?

>> Well, in the short-term one of the -- one of the areas of research that we mentioned in our talk today is looking at as Music educators, can we mediate the effects of enculturation by taking children and immersing them for a period of time in the music of another culture, kind of move them from an outsider's view of that music to closer -- probably not completely, but closer to an insider's view. What kinds of exposure for what length of time might help a -- a cultural outsider understand the culturally familiar music.

>> Likewise we've -- it's very interesting to consider looking at adults who in fact have had extensive musical engagements in multiple cultures. People who are as expert as performing in one kind of music as they are in another kind of music.

>> And theoretically, our -- our measure should allow us to look -- if someone is bicultural -- it's a term that's often used musically speaking -- they should perform equally well in the memory test that we have designed. Other areas that we're looking into, memory is certainly an important cognitive function to study, but there are other musical judgments that could be used to examine the limits of cross-cultural musical understanding, such as rhythmic responses, and responses to tuning and deviant pitches, scale and key, that sort of thing. And some of this work has already been done. We're interested in -- in looking into that, and -- and how it relates to -- to our findings, and also looking at event-related responses, so neuroimaging from the EEG perspective, and how listeners of different culture might pick up on or not pick up on culturally unfamiliar music and its variations.

14. What questions are being studied in the field of music psychology today?

>> I think one of the things that is particularly interesting -- well two things. One is that -- that music is a -- is a phenomenon that psychologists are using to learn more about just how humans process anything. On the other hand, musicians are -- are much more eager to employ psychological, and particularly neuro scientific procedures to learn more about the nature of music, and how it exists in -- in [inaudible].

>> So one of the things that -- that we're interested in, and -- and appearing in a conference like this is certainly a step in this direction -- is having more cross-talk between musicians and psychologists about how we're studying music, what kinds of musical behaviors we're studying, and what impact that has on our understanding of human cognition in general, and human musical development, in particular --

15. Under what disciplines might human musical behavior be studied?

>> You mentioned earlier talent, and one of the things -- one of the places that that can show up if music is marginalized is that, you know, how -- to what extent does music appear in Intro Psych textbooks, things like that. Are we really, you know, initiating young psychologists into the study of music cognition. And it's important to realize that there are a wealth of resources out there. Over the last 10 years studies of music cognition and music and neuro imaging have exploded. We have attended several conferences devoted specific to the neuro science of music. So there are -- for -- for the students who -- particularly who have musical training in their background, and then interested in psychology, there are a number of resources that they can go to to deepen their understanding, and even, you know, find professors on their campus. We have a music psychology class on our campus taught by one of or psych faculty, and then I teach the other music psychology class. And in speech and hearing they deal with music and sound processing from a psychoacoustic standpoint, and in music we do a class on the cognitive neuro science of music. So we're, you know, trying to have more -- it's -- it's definitely an interdisciplinary endeavor, and it will be the next generation, and even the generation after that, that will really make it happen. Because all of us came at it from one area of training, and picked up the other. But now an undergraduate could be a music major and a neurobiology major, and a cognitive neuro science major, and you could actually combine those into -- into something. And we have some students doing that at our university now. Those are the people that are -- I think that'll make the next big breakthroughs in this area."(Morrison, 2013)