Commercial Law: Business Structure

Commercial law on business structure

Business Structure

A large number of different forms of business organisation are possible, whether at common law or under statute. All of them are either subcategories or combinations of three structures: (1) the sole trader, (2) partnership; or (3) company incorporated under the Companies Act 1997 ( ‘the company Act’ of Papua New Guinea’).

In addition, a specialized form partnership known as the joint venture has become sufficiently important in large-scale commercial activities in Papua New Guinea and other countries that it merits treatment as a category.

Many people carry on a business without legal organisation. If a person carries on business by him or herself ( or if any persons working with him or herself in the business are salaried employee), he/she is called a sole trader or sole proprietor. Of course the trader must obtain business licences and fulfil particular requirements of his or her trade, occupation or profession.

But the only legal requirement for a sole trader, apart from laws of general application such as income tax and the licencing provisions already mentioned is that if a person is engaged in a business for trading, manufacturing or mining purposes and use name other than his or her own, the person is required to register that business name with the registrar of Companies Names Act (Chapter(‘C’), 145.

Where two or more people are carrying on business together without a formal organisation, they will be probably a partnership. The Partnership Act Chapter 148 defines partnership in Section 3 as “the relationship that subsists between two people carrying on a business on common with a view to profit.”

People carrying businesses together may not be aware that they are legally in partnership. They may have no formal agreement. There is a good deal of case law concerned with determining whether or not people are in a partnership. Generally, the test is related to the law of agency. If individuals carry on business as agents for other, or on behalf of other, one another, they will be partners.

The Partnership Act, Section 4 gives some guideline for deciding whether or not there is a partnership. The most important guideline is found in Section 4(c), which provides that if a person receives a share of the profits of the business this will be treated as prima facie evidence that that person is a partner in the business.

2 Choosing a Structure

Although persons may without realising it be a sole trader or partners, they may also select one of the various alternative forms of business organising as a matter of deliberate choice.

2.1 Sole Trade

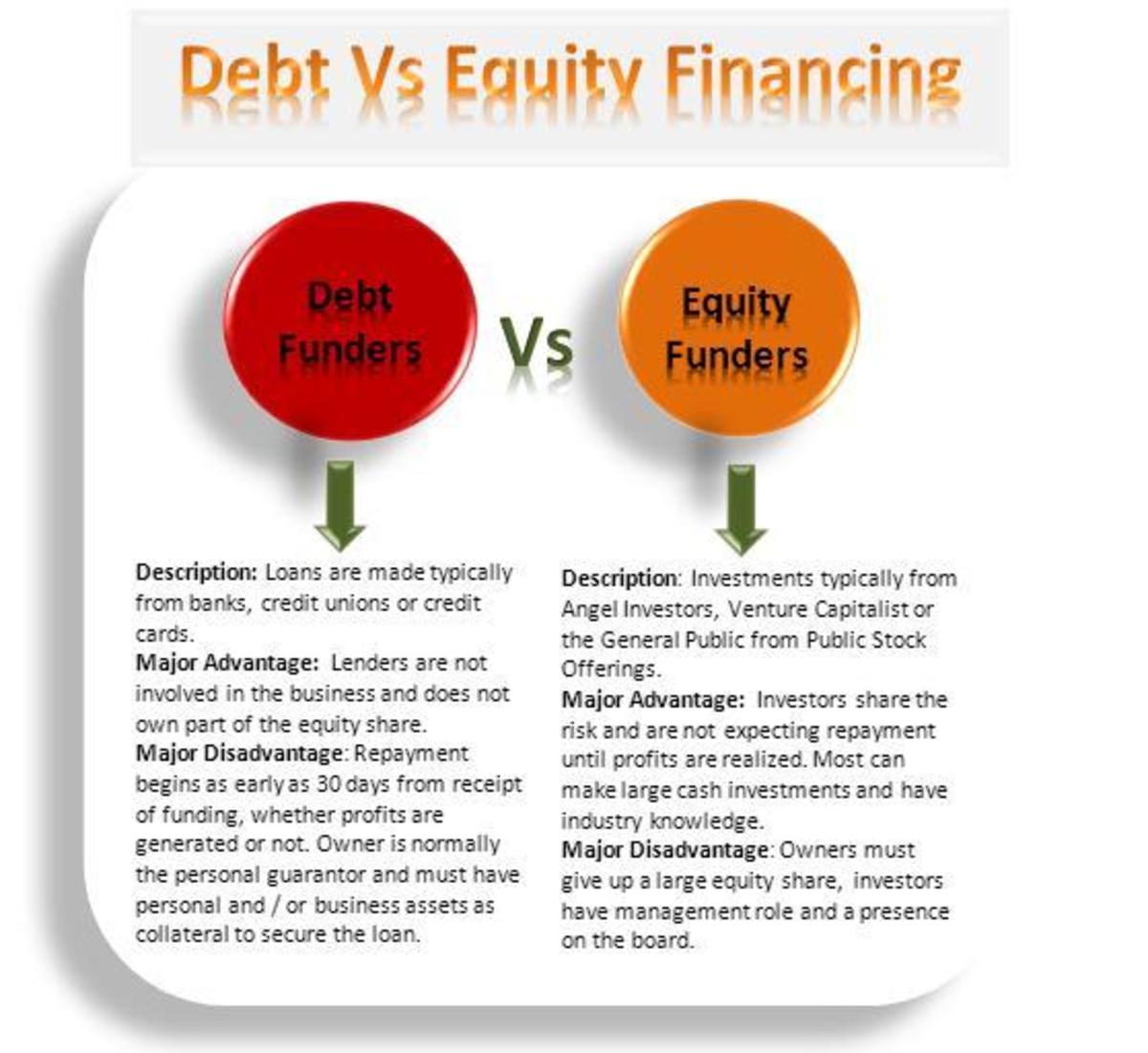

Generally, the sole proprietorship is the simplest form of business organisation. It is suitable only for someone who intends to carry on business for him or herself, perhaps with the help of his or employees. It will not be suitable if other people are expected to participate in the ownership of the business, In particular it does not carry any set out below, especially the possibility of obtaining more investment capital from the participants; of making wise management decisions as a result of discussion among principals; and the spreading and limiting of financial risk if the business fails or large claims are made by creditors or tort claimants. On the other hand, the principal has the exclusive right to make decisions regarding the business, and for many people being accountable to no one but oneself is an advantage that outweighs all others.

2.2 Partnership

If two or more people have decided to go into business together, they may for variety of reasons choose to be in partnership. Some of these reasons are:

-They may be legally unable to incorporate. The Law Society of Papua New Guinea, for example, prohibits lawyers from carrying on their practice of law in the corporate form. Certain other professions have the same prohibitions.

-The organisation of a partnership is simple and inexpensive. There are very few legal requirements for the formation of a partnership. It is much simpler and cheaper than the incorporation of a company under the Companies Act. However, although it is not essential to have a written partnership agreement, it is usually a good idea to do so for obvious advantages that system of rights and duties upon an oral one. The Partnership Act imposes a system of rights and duties upon partners, which they may wish to, vary. For example, under the Act, all the partners are entitled to share equally in the profits of the business. This may not be the arrangement that the partners want to make and they are free to change this private agreement. This only one of many such examples. The preparation of a partnership agreement may be complex and expensive, depending on the needs of the partners and the complexity of their business arrangements.

- In some cases a partnership may provide some tax advantages. For example, if the partners expect there to be losses in the first years of operation of the business, they may want to be partners because in the eyes of the Taxation Office they are individuals and so they can apply these losses as individuals against other sources of income.

There are major disadvantage in a partnership is the liabilities it imposes on the partners. Each partner is jointly responsible for the losses of the business and may also be responsible for wrong acts of his or her fellow partners if they are committed in connection with the partnership business. There is no way of restricting the authority of the various partners of the partnership in regard to third parties or the public at large. Consequently, the acts of one partner in conducting the business, even of not authorized by the others, may bring liability on them all. Partnership is therefore, suitable only for a relatively small number of people who can put substantial trust and confidence in one another.

It is also important to be aware that a partnership often arises by operation of law without the parties having intended to be partnership, and without any awareness of the rights and responsibilities the Partnership Act imposes into their business relationship. Lawyers must take care to ensure that this is clear to their clients.

2.3 The Corporation

Many businesses, both large and small, are carried on in the form of a corporation. The corporation is created by fulfilling the formal requirements of a statute. Companies statute is the Companies Act 1997 for Papua New Guinea, while there are other similar Act of Parliament which significantly for other jurisdictions especially under Common law World and others. It is necessary to have some awareness of the various forms of corporate structure, which exist before you can make intelligent use of overseas case law.

England itself has departed from earlier original statutory models in various ways as its commercial ties the British Commonwealth have loosened and its economy has become more integrated with Europe. Australia significantly overhauled its various State companies Acts in the 1980s and there is now a highly complex uniform company’s code among the Australian States.

There were always several different regimes between Canada and its 10 provinces, and there have been radical reforms in the 1970s through the 1990’s, but there are still several different statutory set-ups there, including one, which closely resembles current Papua New Guinea Act.

Probably of more direct relevance, New Zealand also overhauled its own Act in early 1990s, which was also modelled on the 1948 English Act. Papua New Guinea Investment Promotion Authority (IPA) had instructed the New Zealand Solicitors were instructed to draft the new statute for Papua New Guinea to accommodate the introduction of a stock exchange in 1994, now unknown as the Companies Act of 1997.

The result of Incorporation is the creation of a separate and distinct legal entity. This means that the corporation can sue and be sued in its own name, enter into contracts as can a natural person, including contracts with its own shareholders; and hold property in its own name.

A company is an artificial being, invisible, intangible and existing only in contemplation of law, a separate legal entity from its members (also called shareholders), its liabilities being its own and generally not those of its members. Company is the word commonly used for a corporation engaged in business. Watch for specialised uses of the two words Company and corporation in the statutes and case law, and note that both terms were in use long before company law incorporated under the Companies Act. If you consult Halsbury dictionary on ‘corporation’, you will find that all manner of entities are corporations under the general law, including universities (so that many principles govern the operation of universities which are not contained in University of Papua New Guinea Act or the University of Technology Act); towns; charities. Further, the term company has a number of legally accepted uses, which are entirely outside the ambit of the Companies Act: Law firms, for example, are permitted to call themselves companies (as in “Jones & Company Lawyers) even though they are neither incorporated nor permitted to incorporate.

In the Companies Act of 1997 ‘company means a company incorporated under this Act or any corresponding previous law.’ ‘Corporation’ means a body corporate wherever formed or incorporated and includes a foreign company, but does not include…’ a Papua New Guinea or sole (that is one of the common law corporations referred to above) or a society registered under the Savings and Loans Societies Act.

A corporation is said to have potential immortality, whereas a partnership is automatically dissolved in a number of situations. For instance, if a partnership consists of only two partners and one of them dies, the partnership is dissolved. A corporation, however, does not and even though all its shareholders may change or even though it may for a time have no shareholders. It even continues to exist in a dormant state when it has been struck from the Register of Companies, in that it may be restored and then continues as before.

2.4. Joint Venture

Joint venture is a type of business arrangement in which multiple entities come together using a contract as the basis for governing the collective relationship, but without creating some sort of corporation arrangement in order to pursue the joint venture. This type of approach is common in a number or applications, especially when the venture in question is for short-term purposes only. In many nations around the world, there are few if any regulations that specifically apply to a joint venture, making it necessary to cover as many contingencies in the joint venture agreement as possible.

Since the relationship is governed by the agreement that is adopted by each of the participants, the main task is to work out the amount of resources each one contributes to the venture, and in turn the amount of benefits each one can reasonably expect to derive from the arrangement. Typically, the contract will also address the limit of liability that each participant assumes, as well as outlining provisions for any participant choosing to withdraw from the joint venture by selling his or her interest in the activity. By developing terms that are agreeable to all the entities involved in the project, the chances for proper funding and eventually earning some sort of profit from the venture is enhanced, although there is still always some risk that the project will not yield the anticipated results.

One of the benefits of a joint venture is the relative ease of setting up the working relationship between each of the participants. Since there is no incorporation of a new entity that is jointly held by all the participants, there is no need to create a corporate structure that complies with corporation laws in the jurisdiction in which the joint venture is taking place. While the members of the venture will normally create some sort of steering committee that helps to move the venture along, the exact organization of that committee or group is left up to the members, and can be defined in the joint venture agreement itself.

Another benefit is that once the project is completed, dissolving the joint venture requires a minimum of effort. For example, if the purpose of the venture was to build a new housing development, the participants would see the project through until the development was finished. At that point, the finished development could be sold at a profit to a new investor and each venture participant compensated from the proceeds from the sale. Once the compensation was distributed, the venture would be considered complete and the participants could move on to other projects or ventures.