Creative Conservation: Erosion Control to Stop Flash Floods and Save a Creek

You can trace the old pioneers' drift westward by red cedar trees growing and undermining the heartland's native grasslands and oak and hickory forests. The Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) is native to the Eastern U.S., not the heartland. The pioneers brought it; its wood has many uses. Pencils used to be made of red cedar. With its red heart and sweet smoke, cedar wood was sacred to the Indians. Unfortunately, outside of the Eastern U.S. the cedar is a "weed tree." Cedars grow quickly and have tough little seedlings that grow up mere inches in front of native seedlings, sucking up water and shading them out. One source says that one acre of cedar trees drinks up 55,000 gallons of water a year.

Some people are sentimental about cedars because they are pointed evergreens that look like Christmas trees. Meanwhile, cedars denigrate natural heartland features such as forests and glades, which are sunny rocky outcroppings on hillsides and homes to native wildflowers. Conservation groups will often make a day of chopping down cedars to restore a glade. You can tell, in the Midwest and the Ozarks, when forest land is not properly tended to. It's full of cedars. Forest and prairie fires used to control them, but we don't allow natural burns anymore. The Plains States actively battle cedars; they ruin prairie land.

That said--in the eastern Ozarks there was a pretty little creek. A curvy two-lane highway was built on the centuries-old path alongside the creek. It was a nice area: People built houses in developments called Deerview and Wilderness Trails and Sunset Hills. Hilltops were shorn of trees so that houses with five-car garages could be built on top. The creek was the area's pride. It ran over rocks and made waterfalls. It offered wading, fishing, and swimming holes. Deer, wild turkeys, raccoons and foxes drank there. Every few years, beavers built a dam or two.

Then something changed. During storms, flash floods roared down the creek. At its bend the water slammed into the bank, eroding the soil. The exposed soil began falling off in chunks. Mature oaks and sycamores lining the creek bank got waterlogged and one by one, they fell. The banks grew bare. Soon the creekbed was a muddy channel six feet deep and widening with every storm.

Residents argued about how this happened. They blamed developers. They blamed the beavers. They said too many paved roads caused too much runoff after rainstorms. As the creek widened so did its floodplain, and it carried off backyard furniture and bikes and empty paint cans. Then, after a really heavy rain, it covered the highway, blocking access to hundreds of homes. The detour meant driving 10 extra miles.

The most practical people now wanted culverts and concrete to make the creek into a canal. Other residents called the state Department of Conservation.

Waste Not

The Department marked the area where the creek bed erosion was the most critical. Then it chopped down all the nearby cedar trees.

What? the people said. They thought trees helped prevent erosion.

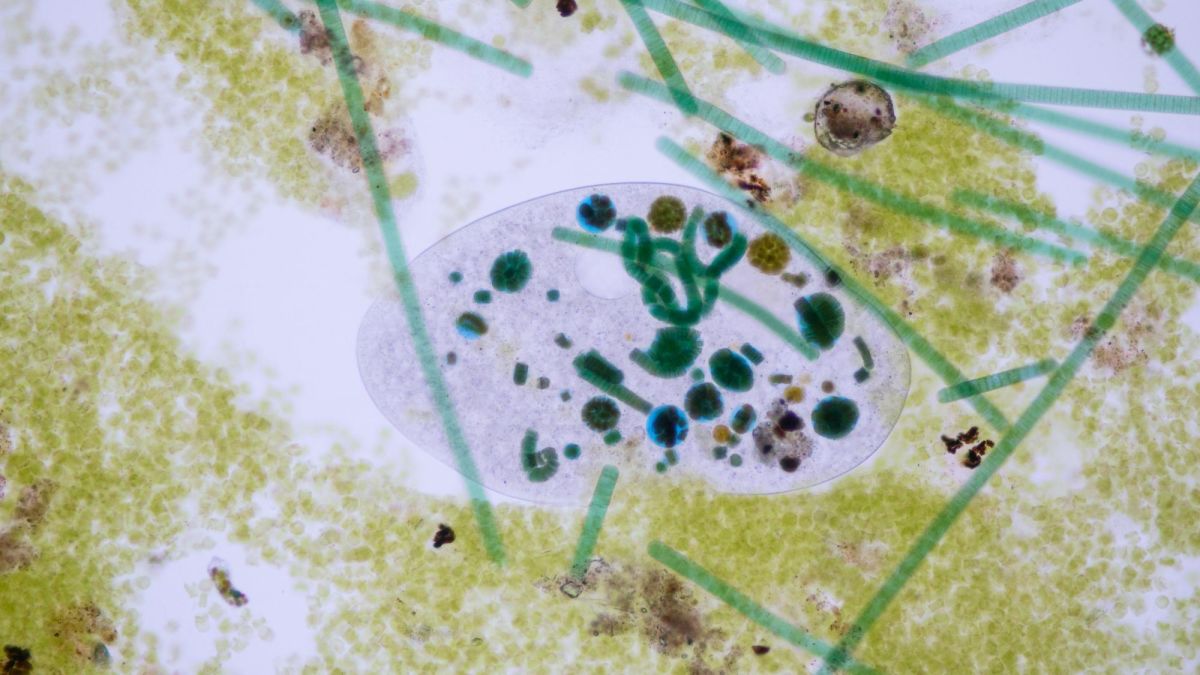

The conservation team didn't let the "weed trees" lie, nor did they make a bonfire of them. They anchored the cut trees sidewise into the creek bank, halfway into the water, and filled in the slope with some soil. Now the cedar branches not only held the new soil but also provided habitat for water creatures. No plastic or asphalt was necessary.

Then the department called for volunteers. It provided a thousand "sandbar willow" (Salix exigua) shrubs for volunteers to plant on the creek banks, in rows like crops. Fast-growing willows would stabilize the creek bank and give other native trees time to grow.

The creek erosion took ten years. The restoration took only 5 days. It also took an earth mover, some trucks, a thousand free tree slips from a state nursery, and a group of volunteers. You can see in photos what was done. Looks a little irregular. But it will save the beloved creek.

The Conservation Department has a lot where families can drop off their dried-out Christmas trees after the holidays, and the Department dumps them by the ton into lakes to create underwater habitat for fish and other water creatures.

Nobody hates Eastern red cedars; they just have different uses for them.