Correlations Between the Haitian Revolution and the United States Civil War

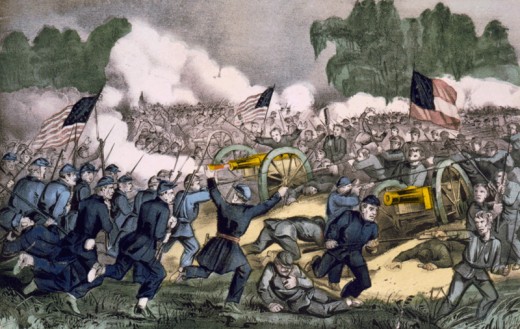

The Haitian Revolution and the United States Civil War

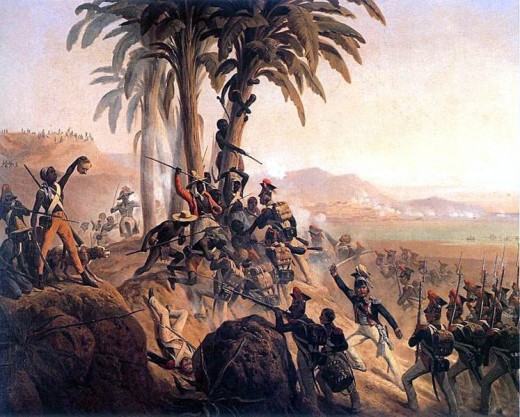

The end of the Eighteenth Century is commonly referred to as the age of Atlantic Revolutions, an age that began before 1791 on the French island of St. Domingue, modern day Haiti, but Haiti was where the first true revolution took place. The revolt in Haiti would have global repercussions that is now only being fully appreciated; it was the first large scale slave revolt in the New World. Following the slave revolt Haiti would be only the second independent nation in the New World, second to only the United States and it would make Haiti the first independent nation to be governed by an administration consisting of former slaves. The Haitian Revolt encompassed every imperialist nation on the planet at any one time; the French, the British, and the Spanish all played a major role at one time or another. This however is not the only impact of the Haitian Revolution, while this is significant to be certain, the real impact of the Haitian Revolution can be found in the influence of the both sides of the slavery issue in the United States and the gathering storm that was to be the U.S. Civil War. In fact, the Haitian Revolution, whether looked at as inspiration for American slaves or as a cautionary tale for American slave owners, had a profound influence on antebellum America and directly led to the United States Civil War.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century there was no more prized imperial possession of the French than St. Domingue (modern day Haiti), it was in fact the richest colony in the world. When one considers the stats from St. Domingue they are truly staggering; forty percent of France’s total foreign trade, forty percent of the entire world’s sugar originated there, and nearly fifty percent of the world’s coffee was grown there (Benjamin, p.229). Much like their neighbors to the north, the entire economy of St. Domingue was based on the subjugation of African slaves, over half a million total, that were owned and controlled by less than twenty-five thousand white plantation owners (Benjamin, p.230). In an effort to pacify the subjugated people of the island, and guard against a slave uprising against their rule, the island’s governing body in France attempted to implement a series of perceived rights and protections for the enslaved people of the island. The French Code Noir were frequently ignored due to the fact that the production of the people of St. Domingue was so vital to the French crown any change would been seen as an affront to the King and a serious hit to the royal wallet (Danton, 2005).

Two years before the slaves of St. Domingue would cast off the shackles of their enslavement an “enlightened” revolution broke out in the imperialist home of France. The French Revolution has since become known for the movement from monarchy, aristocracy, or theocracy to government more concerned with equality and the so-called “rights” of man. Following a relatively short rebellion, a republic was established to govern France and the former monarch, Louis XVI, was executed and a series of widespread reforms were implemented (Doyle, 2002). The new Estates General in France passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen and instantly brought the question of slavery to the forefront of any discussion of human rights (Corbett).

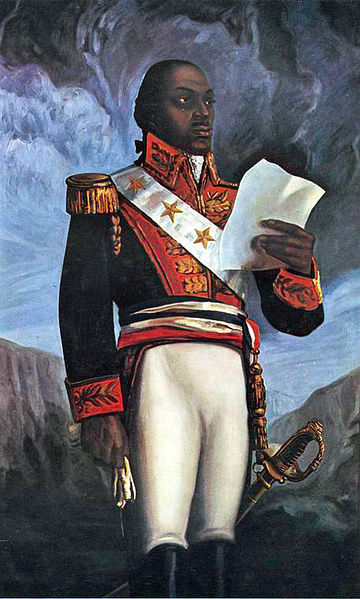

By the time word of the French Revolution had reached the Caribbean island of St. Domingue, the coals of rebellion were already smoldering on the island. Unrest among the slave population of St. Domingue had been brewing for many years, under the leadership of François Dominique Toussaint Louverture the slow simmering anger exploded into full blown revolution. When the fighting broke out in 1791, the forces of the rebelling slaves were initially very successful but soon found their rebellion contained. Toussaint, who joined the rebellion as a medical officer, was a former Creole slave that took command of the ragtag forces of rebelling slaves, under his command the unorganized bunch became an effective fighting force (Corbett). By 1793, the revolt had effectively been put down but when the islanders learned of the execution of Louis XVI they became very suspect of the Frenchmen that were at the time negotiating terms of surrender. In the chaos that followed the breakdown of negotiations, the commander of the French forces on St. Domingue, Sonthonax who was now facing an imminent invasion by the British Navy and desperately needed reinforcements, freed all slaves on the island of St. Domingue in 1793, a move that would have global implications when the French General assembly ratified the move in 1794 (Corbett). The Haitian Revolution would ultimately involve forces from France, Britain, Spain, and the slave army of which Toussaint would ultimately take command of and lead them to victory over their French oppressors in 1803, making Haiti the second independent nation in the New World, following only the United States.

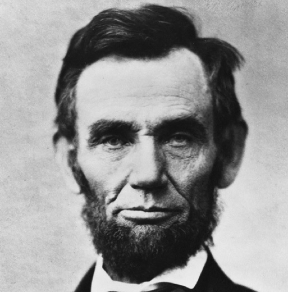

The implications of the Haitian Revolution on slavery in the United States and the impending United States Civil War began in 1793 when the fighting on the island forced several hundred refugees to flee the island led to a massive immigration of whites and their slaves to land in Norfolk, Virginia. Upon their resettlement in the United States the immigrants began to lobby for U.S. involvement in Haiti. These immigrants and their slaves were the first to begin to foment unrest among American slaves and abolitionists. The behavior of these immigrants as well as those of radical Europeans living in the U.S., and mistrust among their American hosts led to the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. The presidential administrations of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson further complicated the situation due to the fact that they approached the Haitian situation in polar opposite methods. Adams was fundamentally opposed to slavery and felt no compunction to aid the slaveholders in Haiti, and for Jefferson’s part he was conflicted. Being a proponent of the ethics promoted by the French Revolution but also being a southern slaveholder led him to send minimal aid to the French forces in Haiti. Both men, however, shared a common concern in their approach to Haiti; they were both concerned that the slave uprising could spread to American shores (U.S. Dept. of State).

The loss of Haiti as a jewel in the French crown would have considerable repercussion for the United States and the future of slavery there within. As was previously mentioned, Haiti was the wealthiest French colony and had provided vast wealth for France as a whole, with that now gone Napoleon would need to find a new source of income. In one fell swoop, Napoleon would rid himself of one of France’s largest monetary expenditures and replace some of the money lost with Haiti; the Louisiana Purchase. While panned at the time, the Louisiana Purchase has turned out to be mutually beneficial to both the United States and France. The purchase more than doubled the size of the United States and for France, it simultaneously jettisoned a proverbial money pit and aided in balancing Napoleon’s accounts (Munro & Hackshaw, 2005).

The Louisiana Purchase would impact the course of slavery and the Civil War in the United States in two ways; first the 1811 slave uprising there, including many men that had participated in the Haitian Revolution, would shine a glaring light on the real threat of a slave revolt in the United States (Burman, 2008). Second, the new land acquired through the purchase would result in number of new states for entry to the Union, the debate regarding whether they would be Free States or Slave States is one of the primary direct causes of the Civil War (Munro & Hackshaw, 2005).

It is easy to imagine that the fear of a slave insurrection would be a constant concern for the slaveholders of the American south. The close relationship between French Louisiana and St. Domingue, and the world changing rebellion that began in St. Domingue in 1791 and racial strife in the Louisiana Territory was at a fever pitch before even before Napoleon decided to rid himself of Louisiana. The tipping point came when several thousand Haitian exiles arrived in Louisiana after fleeing the fighting in Haiti and a brief stay in Cuba, causing a massive influx of outsiders and men who had seen the success of a slave insurrection in Haiti. The racial tension, before already simmering, now completely overwhelmed those in charge in Louisiana. Finally, with a declaration by Charles Deslondes, a slave in the Louisiana Territory, for all of his fellow slaves to kill whites and demand that they be set free, a full blown slave insurrection engulfed the territory (Buman, p.5). This so-called German Coast Uprising, named as such because the uprising began in a region originally settled by Germans, only lasted three days but involved anywhere from two hundred to five hundred slaves at its height, making it the largest such uprising in United States history. The 1811 German Coast Uprising affirmed the fears of many Americans, that a major slave insurrection was only a matter of time, though the uprising failed the seeds of doubt had been sewn and many viewed the Haitian refugees as the primary instigators (Buman, 2008).

The territory brought into the Union by the Louisiana Purchase would be become the states of Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska; as well as parts of Minnesota, Wyoming, Montana, North and South Dakota, Colorado, and parts of two Canadian provinces (Ambrose, 1996). The issue of admittance to the Union and slavery would be one of multiple catalysts that would push the nation to civil war, slavery in the south was institutionalized but its expansion west was unacceptable to many. The conflict at the federal level would begin in 1820 when Congress passed the Missouri Compromise which admitted Missouri to the Union as a slave state and Maine as a Free State, the compromise went further and outlawed slavery anywhere north of Missouri in the Louisiana Territory; territory acquired in the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution. This was a temporary victory for those opposed to slavery spreading west with the country, it was repealed in 1854 with the Kansas-Nebraska Act (Library of Congress).

The Kansas-Nebraska Act legalized slavery in the new territories but granted the people of the new states the power to choose whether they wanted to allow slavery in their state when it entered the Union, a premise known as popular sovereignty. Proponents of popular sovereignty believed that if given the option, people would find it within themselves to ban this peculiar institution and end the westward expansion of slavery. Whether or not that was true would never be determined, shortly after the act was passed violence broke out between advocates of slavery and those opposed to it, plotting the course to civil war (Library of Congress). The conflict on the frontier of the United States’ westward expansion would be further complicated by the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857. This decision declared that slaves were not U.S. citizens and therefore could not sue in federal court; it also deemed the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional and declared that Congress did not have the authority to prohibit slavery in the territories (Library of Congress).

By the time of the Dred Scott decision, slavery was a blight on the record of a nation purported to be based on the premises of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Many, by this time, were opposed to it but since it had been so institutionalized in the South for so-long they made an effort to look away. One thing that many simply would not allow to happen was to allow that institution to spread like a cancer to the newest territories and future states. The battle over whether or not to allow the new states and territories the opportunity to enter the Union as a Free State or a Slave State would be just another match to the already fanned flames of civil war, instigated by the outcome of the Haitian Revolution.

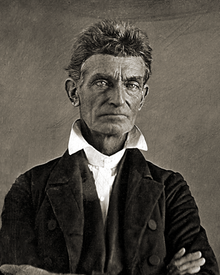

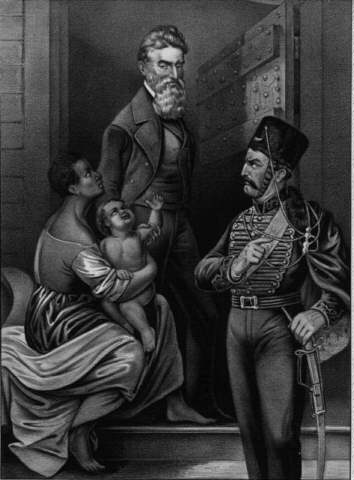

Francois Dominique Toussaint Louverture, was described by the French historian Alphonse Beauchamp as “One of the most extraordinary men of a time when so many extraordinary men appeared” (Clavin, p.117, 2008). Louverture was a former slave that joined the rebellion as a medical officer, during the early days when the slave army had been allied with the Spanish in the battle for St. Domingue (Corbett). Following the proclamation by Sonthonax that freed all of the slaves on St. Domingue, Louverture and his slave army switch allegiances and fought with their former oppressors against the British and Spanish; ultimately opting for their own path and fought off all outside influences (Corbett). The spectacular rise of Toussaint Louverture from slave to victorious commanding general would be the stuff of legends, and would inspire dissent, most prominently in the person of John Brown.

The man that was John Brown, cut his radical abolitionist teeth during the proxy war between proponents of slavery and those opposed to it in Kansas from 1854-1861 and carried his obsession on to his ill-fated attempted to seize the United States Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859 (Etcheson, 2006). Not only did Brown and his men openly carry on the memory of Louverture and the extremely violent tactics of Louverture’s men during the Haitian Revolution but Louverture had also greatly influenced the men behind the raid, the money men. Not long before the raid on Harpers Ferry occurred Francis Jackson Meriam, visited Haiti with a radical abolition writer, James Redpath to seek inspiration and report on the conditions in the years since the Haitian Revolution occurred (Clavin, 2008).

When Brown and his followers stormed the United States Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry they did so under the guise that any and all slaves in the vicinity would join their effort. Indeed, when the men were planning the raid they fully anticipated starting a full fledge slave insurrection similar to the one that liberated the slave in St. Domingue (Clavin, 2010). John Brown’s dedication to the end of slavery and freedom for slaves in the United States is not in doubt and neither is his knowledge and understanding of the Haitian Revolution and Toussaint Louverture. At one point, during the fighting in Kansas, John Brown was helping to lead some escaped slaves to freedom. While resting overnight Brown recited, from memory, the history of Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution (Clavin, p.142, 2008). Certainly no one is advocating the notion that John Brown or his raid on Harpers Ferry started the Civil War. What is indisputable is the fact that John Brown and his raid was the product of an increasing hostile atmosphere in this country prior to the Civil War. The influence of Toussaint Louverture and the success and brutality of Haitian Revolution aided in the hostile atmosphere and actually helped to propel the country toward war.

“The events in Haiti had a profound impact on the American mind; they were a constant reminder of the possible outcome of any society built on the bedrock of slavery” (Clavin, p.118, 2008). At one point, many southern slaveholders were convinced of and preparing for a Haitian slave landing and invasion of South Carolina (Munro & Hackshaw, 2005). That southern slaveholders would be concerned of any such invasion or a slave insurrection is a perfectly logical concern, after all white southerners were far outnumbered by the slaves that they continued to subjugate. There is ample evidence to support the notion that the events in Haiti, both directly or indirectly, helped to propel this country toward civil war, and interestingly enough would transform Robert E. Lee from the man who helped to put down the Harpers Ferry raid into an enemy of the United States six years later (Clavin, 2008). When Thomas Jefferson approved the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from the French in the wake of the Haitian Revolution he unknowingly provided a major impetus for the future war between the states.

Copyright© 2014 RLB; all rights reserved.

References

Ambrose, S.E. (1996). Undaunted courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the opening of the American west. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Burman, N.A. (2008). To kill whites: The 1811 Louisiana slave insurrection. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Clavin, M. (2008). A second Haitian revolution: John Brown, Toussaint Louverture, and the making of the American Civil War. Civil war history, 54(2), 117-145.

Clavin, M. (2010). Toussaint Louverture and the American civil war: The promise and peril of a second Haitian revolution. Philadelphia, PA: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

Corbett, B. The Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803. Accessed on May 25, 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/revolution/revolution1.htm

Doyle, W. (2002). The Oxford history of the French Revolution (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Etcheson, N. (2006). Bleeding Kansas: Contested liberty in the civil war era. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

Kachun, M.A. (2006). Antebellum African Americans, public commemoration, and the Haitian revolution: A problem of historical mythmaking. Journal of the early republic, (26)2, 249-273.

Munro, M., Hackshaw, E. W. (2005). Introduction: reinterpreting the Haitian revolution and its cultural aftershocks. Small axe, 9(2), 8-11.

The United States and the Haitian revolution, 1791-1804. The U.S. Department of State: Office of the Historian. Accessed on May 6, 2012. Retrieved from: http://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/HaitianRev.

The United States Library of Congress. Primary documents in American history: The Missouri compromise. Accessed on May 27, 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Missouri.html

The United States Library of Congress. Primary documents in American history: The Kansas- Nebraska act. Accessed on May 27, 2012.

The United States Library of Congress. Primary documents in American history: Dred Scott v. Sandford. Accessed on May 27, 2012.