Death of a Language - Reaction on the BBC article "The death of language?"

It is said that language is more than just a means of communication. It is not limited to expressing ourselves in the most basic sense, like when we want people to know we’re in danger, or if we’re hungry, or if we merely require their attention. Therefore, language is beyond all that. Language identifies us; of our culture, our origin and is basically a big part of who we are.

In our house, we speak different languages or dialects, if you must call it, depending on your frame of reference. We speak Masbateño, Bicolano, and Waray, apart from “the necessary” in Central Visayas, Tagalog and Cebuano. My Mama from Samar, Papa from Masbate, all residing here in Cebu made this possible. It would also be needless to mention all the other languages spoken by our neighbors, our nannies as we were growing up, our friends, colleagues, who, through day-to-day interaction have taught us a thing or two about their language, and their culture in general.

What happens if any of these languages ceased to exist? If no one speaks Waray anymore, would anyone still pinpoint which part of the map my mom is from?

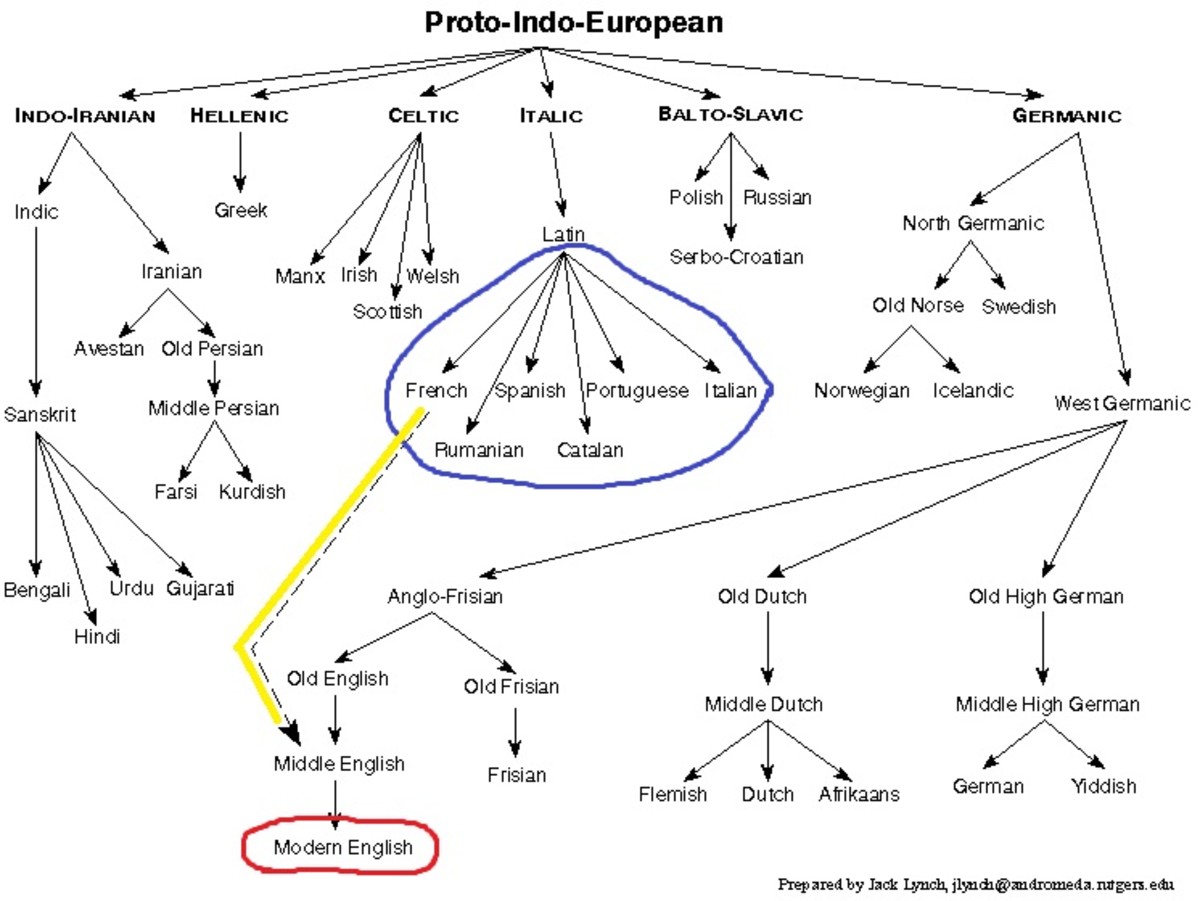

As stated on the article, the renowned linguist Claude Hagege claims that by the year 2100, 90% the world’s languages would have died. With 473 endangered languages, I believe this is quite possible. Little by little, every community, especially those who have previously isolated themselves, seek to interact with the rest of the world. In effect, some languages are devoured by the more dominant ones.

But what really happens when we are inclined to a more unified language, specifically English? Are the other languages just a necessary casualty in the path to progress?

The English language has paved way for the Filipinos to become highly in demand here and abroad. Of course, that’s beyond the fact that we are also a very versatile, hard-working, patient and cheerful people. We have these call centers, Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) companies and many foreign companies employing millions of people for a variety of industries. We obviously don’t need to enumerate the economic and industrial advantages of being fluent in global English.

When we have something like English to use, why bother with our native languages? More often than not, they’re outdated, impractical at times, and incapable of riding the tides of change. The main concerns of the language of the minorities are that there is no real equivalent to words used in commerce; technology and other technical terminologies essential to every country, every nation, and these native languages are simply inadequate anyway.

But it’s never just black and white.

Just last week, my cousin from California and I were listening to my Uncle’s age-old Bisaya jokes. Having spent most of his childhood here, he was still very much a true blue Cebuano even after many years of living in the states. Anyway, we ROFL’d the whole time and thought it to be a good idea to share it with his friends back in America. After several attempts, we realized the jokes were simply “off” when translated to the English.

If it were at all possible for the Cebuano-Visayan language to die, it’s not a wild guess to say all those jokes and stories would die with it. Not to mention the many other forms of literature and cultural heritage. There are just too many things we can only express most accurately, most appropriately and with the best delivery in our native tongue. The same thing will happen to those languages they consider endangered.

Sometimes, the efforts in keeping a language alive are merely to satisfy the vanity of linguists and historians. The thoughts are not really shared by those who were born with the language.

The death of a language is in the hands of many. In my opinion, the matter is up to the community or nation concerned. If indeed all the world’s words came from one single point of origin, then maybe it’s just natural we consolidate what we know, and speak in one tongue. And maybe, just maybe, after several decades, we would again divide ourselves in to dialects or versions of that language, which will eventually be unique in its own. History repeating itself once more.

Suffice to say, language death is both bad and good, on an independent perspective. Who decides are not those looking into the microscope, but the ones being looked at.