Digging up the Past - What is Archaeology?

Defining Archaeology

"If History is bunk, then Archaeology is junk. This bizarre subject entails seeking, retrieving and studying the abandoned, lost, broken and discarded traces left by human beings in the past. Archaeologists are therefore the precise opposite of the dustmen, though they often dress like them." (Bluff Your Way in Archaeology - Paul Bahn 1989)

In it's simplest terms archaeology is the study of past human cultures which means we do not do dinosaurs, ever (unless of course we are on holiday and fancied giving palaeontology a go). But what it does mean is that as archaeologists we do spend much of our time investigating other peoples rubbish. The big flash finds which grab the news headlines are rare events, happening only to the lucky, most of the time it is back breaking, monotonous work - especially for the newbie, but I am getting ahead of myself and that is a topic for another article.

Archaeology is however much more, it is a systematic study of the past, where all aspects, all material culture is recovered with care and described in great detail.

"The primary aims of the discipline is to recover, describe and classify this material, to describe the form and behaviour of past societies, and finally to understand the reasons for this behaviour." (The Penguin Archaeology Guide ed Paul Bahn 2001)

In order to do this archaeologists utilise a wide variety of methods, some of which I will be discussing in later articles. Archaeology is a truly interdisciplinary subject, geology, biology, chemistry, physics, maths, English, history and many more have all contributed to the myriad ways in which archaeologists have chosen to study the past. Each adding their own special piece of the puzzle.

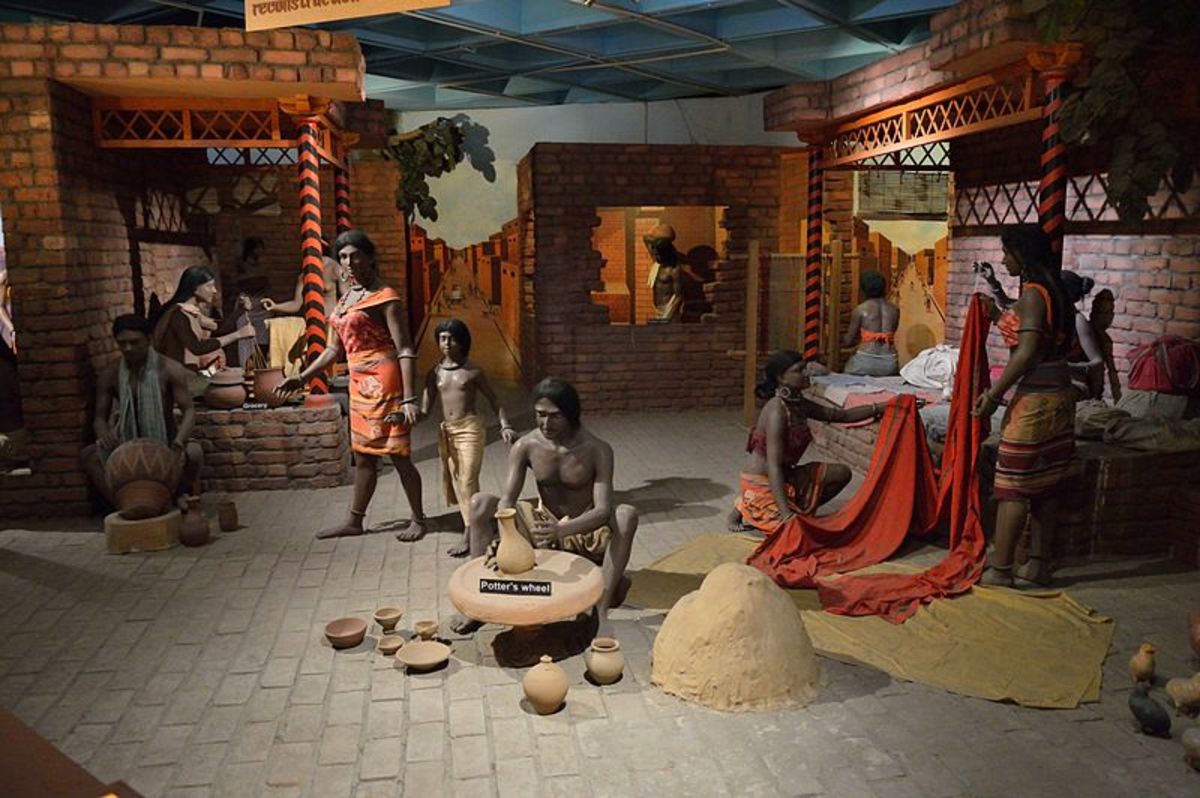

Material Culture

In the previous section the term 'material culture' was mentioned. What is material culture? Well in essence it is anything and everything ever made, repurposed or used by humans in their daily lives. It can constitute artefacts as small as the flint tools from the Mesolithic known as microliths or it could be a part of broken amphora from the Mediterranean world of Romans and Greeks or it could be site as large as a Mayan temple.

For archaeologists the majority of our evidence for past societies we study will come from the material culture. It's importance cannot be stressed enough but what is also important is how this material is recovered and the recording of it (to be dealt with in a later article). Often the information gained from simply recording where something is found, the context, can provide the archaeologist with just as much information then the artefact alone.

The photos below depict first the great monumental site of Carnac in Brittany, France and secondly a handful of sherds found eroding out of a beach cliff in Cornwall. The latter are not as impressive as the material culture we see in the first picture however, they do represent an important part of the economy at a certain time and place. They are pieces of briquetage from a Roman period salt production site - salt production at this time was extremely important not only as a means of paying the Roman military but also in the preservation of food.

Most artefacts are recovered as part of a site, (although some are occasionally classed as 'stray finds') which brings us to the next question.

What is a Site?

An archaeological site can be defined in a similar manner to material culture.

"Any place where there is evidence for past human behaviour." (The Penguin Archaeology Guide)

So like material culture it can be as small as a single random find or as large as temple complex. Archaeological sites are a component of a past societies material culture and as with artefacts they should be treated with care and recorded meticulously.

Sites are often classified according what they were used for, however, the terminology can differ depending on where in the world you are. There are many different types of site, as a small exercise break down your present day world into the variety of sites you would use in your daily life. For example, your house/apartment is one - a habitation site; your place of work is another - a workshop/working area; the supermarket - a food procurement site; your local club - a communal meeting site; the Church - a ritual site. The list can go on.

Deciding what a site was used for is done by analysing the artefacts found within it, this is why when we find an artefact it's position is recorded carefully. Collection of artefacts on a site with a similar function can give the archaeologist an understanding of the sites history. For example, if a stone artefact such as the one in the photography below was found, the archaeologist would classify it as quern stone for grinding grain, these types of querns are usually prehistoric (in the UK) and tell us that the occupants of this site had access to grain and knew what to do with it, but also that in all likelihood this was a domestic/habitation site.

Features

Should you ever have the pleasure of visiting an excavation or even working on one you will hear the word 'feature' bandied around. A feature is an archaeological term for a part of the site yet to be classified - essentially a site is made up of a series of features and associated artefacts.

So a feature can be a single posthole (a circular feature which is usually darker than the surrounding soil) where a post was once placed but has now rotted away, it can refer to a collection of postholes which would then possibly make a building. A feature can be a stone wall (please remember that if you get more than three stones in row, it's wall...wink, wink), it can be pit, it can be anything that is part of the site and has been created by human hands.

Below is an example of a feature found on a Roman site in Northern France - it is a roadside well.

Favourite Archaeological Sites

Which would be your must-see archaeological site?

Stratigraphy

One of the most fundamental principles of archaeology which all students must get their heads around is the concept of stratigraphy. For those who already know a bit of geology, this should not be new to you, archaeology has borrowed from geology and made stratigraphy its own.

So what is it exactly? If you are on an excavation you will invariably start to dig from the top, removing each layer as it is detected (more on that later), the basic principle sees the excavator as peeling back the layers of time. The most recent layer in time would be the top layer and the oldest layer would be the one at the bottom, all within an archaeological context with its corresponding artefacts and features. Of course it is a bit more complicated than that but you get the general idea.

"Stratigraphy is the principal means by which the context of archaeological deposits is evaluated, chronologies are constructed and events are sequenced." (The Penguin Archaeological Guide Paul Bahn 2001)

There are four underlying principles which rule our use of stratigraphy (and because there is no way I could write them as succinctly as my trusty Archaeological Guide you'll have to put up with another quote).

"1. law of superposition - older beds or strata are overlain and buried by progressively younger beds or strata;

2. law of cross-cutting relationships - a feature that cuts across or into a bed or stratum must be younger that that bed or stratum;

3. included fragments - fragments, material or debris from an older bed may be incorporated in a younger, but no vice versa;

4. correlation by fossil inclusions - strata may be correlated based on the sequence and uniqueness of their floral and fauna content"

Do no panic if you are not quite sure what I am talking about, hopefully by the end of this series of articles it will be as clear as glass.