Early Modern Europe and Enlightened Thinkers

The underlying principles and assumptions demonstrated in the works of several enlightened thinkers indicate a homologous progression of thought which was unique to the early modern period. That being said, each enlightened thinker harbors his own interpretation of how progressive thought ought to be applied to the modern world. Therefore, the extent to which enlightened thinkers demonstrated a unified approach to interpreting and applying rational thought is fractional. Though the term ‘enlightened thinker’ suggests a homogenized definition; the great thinkers who are classified within this category demonstrate very different understandings of the world around them and how it ought to be progressed.

Several points exist which many enlightened thinkers touched upon in their respective treaties’. These include a discussion of the state of nature, the law of nature, and the social contract as indicated by these natural laws. Though it seemed a criterion of enlightened thought that these notions be theorized upon, the theories which emerged out of this rational consideration varied drastically and consequently had differing effects on philosophical and political thought since their inception. Immanuel Kant summarizes the momentum of the enlightenment thusly: “Enlightenment is man’s release from his self-incurred tutelage” which at the basic level demonstrates that man’s ability to break away from his rational immaturity is the application of reason.[1] Enlightened thinkers therefore, represent those men who were attempting to do just this. That being said, though these philosophers may have managed to relinquish their mental naiveté, their conclusions are by no means harmonious with one another but rather, they represent an in-sync attempt to progress man’s understanding of himself in relation to the world he lives in.

The enlightenment must be considered as a gradual movement in order for the thought processes which emerged during the era to be accurately understood in relation to their context. For the most part European nations prior to the enlightenment period were politically dominated by absolute monarchs and the societal impact of this reality also bred intellectual commentary. Jacques Bossuet exemplifies such commentary as he attests that Kings are indeed overlords over their Kingdoms and that their job is to lead the people according to God’s law. He writes: “O kings, exercise your power then boldly, for it is divine and salutary for human kind, but exercise it with humility”.[2] Further, he maintains that to question a King is sacrilegious and that “the Prince need render account of his acts to no one”.[3] Therefore, not only should Kings be unquestionable, but the only protection for the individual from the public authority of the King, should be the innocence of the individual. Although enlightenment thought did not necessarily vary from this outlook, excerpts like those written by Bossuet can demonstrate the political atmosphere and pressure out of which enlightened thinkers emerged with their various social diagnostics.

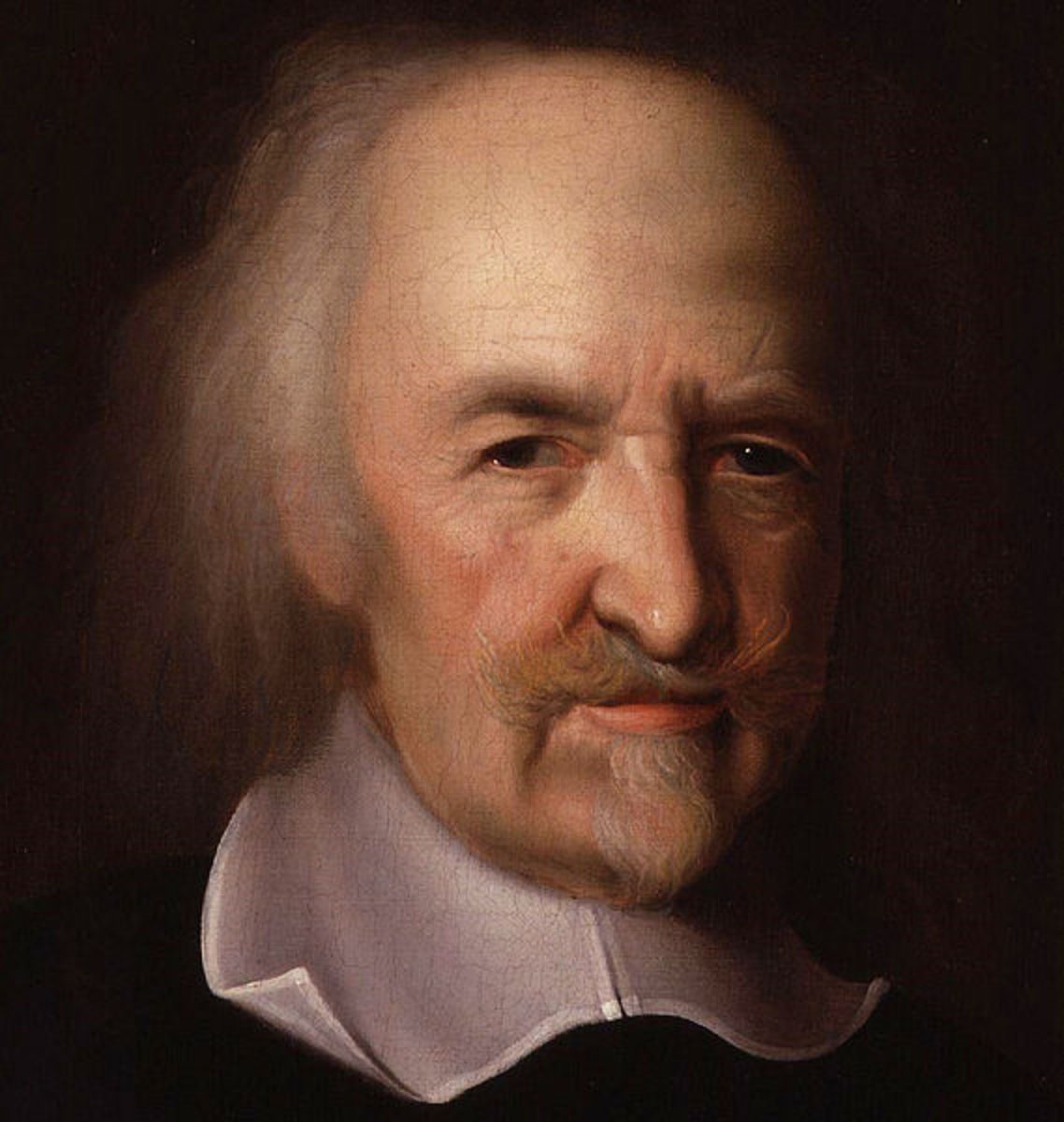

A topic of great concern among enlightened thinkers was the theory surrounding man’s state of nature. Generally, the enlightenment served as an intellectual movement which emphasized reason over religious dogma. Enlightened thinkers therefore sought to discover the natural laws that directed human activities and society. Almost every enlightened thinker that emerged during the movement entertained a theory regarding the state of nature but a couple contrasting models separate the lot of them. One of these models was theorized by Thomas Hobbes, according to whom, man in a ‘state of nature’ is a man continually at war. This theory maintains that it is every man for himself in a state of nature as:

“whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of war, where every man is enemy to every man, the same is consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them withal…the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”.[4]

A conflicting model which also identifies the state of nature among man was contemplated by John Locke who maintained that the state of nature has a natural law to govern it. This law is reason. With the guide of reason then, Locke surmises that no man could reasonably jeopardize another man’s “life, liberty or property”.[5] For Locke, the state of nature is a condition of unspoiled and naturally occurring freedom and equality. Different again, is Rousseau’s understanding of the state of nature. As discussed above, Hobbes believed that in a state of nature man was at war; in comparison, Rousseau reads that in a state of nature men are free and equal which sounds similar to the Lockean model. However, Rousseau uses the terminology “noble savage” to describe men who are left apart whereas civilization corrupts them. Men apart from civilization who are in a true state of nature differ from animals in their capacity to exercise free will and self-improvement.[6] Though these theories seem to vary significantly from one another commonalities exist as each enlightened thinker advocated the equality of men in both body and mind though their determination of this equality was of varying capacities.

The law of nature is another focus which enlightened thinkers were similarly obsessed with considering. The mutual interest in this concept stemmed from a societal and individual desire to challenge the divine right of kings, in place of which, enlightened thinkers offered varying theories regarding natural rights and how they played into a wider social contract between humans. In comparing and contrasting the theories of different enlightened thinkers several similarities become apparent. Hobbes and Locke share particular similarities in this discussion as they both dictate that all humans have natural rights and therefore natural law is indiscriminately applicable to all peoples. For Hobbes and Locke, the fundamental law of nature among mankind is self-preservation. Rousseau varies from the previous theories however as he does not believe it is justifiable to cause another human pain in the interests of self. Furthermore, he maintains that the emergence of natural rights instilled inequalities among men as men grew corrupt and greedy and began taking as his, things that he did not necessarily need. According to Rousseau morality is not ingrained in man, but rather, morals are an inevitability produced by inequality.[7] Consecutively, in Voltaire’s Candide, it becomes apparent that Voltaire as an enlightened thinker is not sold on any consistent idea. On the one side he does not agree with naïve optimism regarding natural law, neither did he believe in the idea of a perfect God creating perfect world but he still showed renewed interest in the pursuit of theology, arts and sciences; a belief which was exonerated especially through the characters of Candide and Pangloss in the work.[8] In reading Voltaire’s work it is exceedingly difficult to single out one character as having upheld Voltaire’s direct belief system because they all work together and add different facades to a work which is meant to present a satirical understanding of religious and philosophical themes. The book in its entirety, therefore, works as a representation of Voltaire’s own views and is written as a fictional commentary of the times.

As previously mentioned considerations regarding the state of nature and the parameters of natural law were the direct result of enlightened thinker’s interest in understanding how society functioned naturally and how improve their contemporary society through these understandings. With that in mind, the social contracts which came to be understood by enlightened philosophers demonstrate the pinnacle of how they believed reasonable men should co-exists in society. Out of this intention, several significant understandings emerged. One of the most complete understandings of the social contract was mapped out by Rousseau. Rousseau defines the social contract as a method of associating which will defend and protect-using the power of all people-the person and property of each individual member but will still enable each member of the group to obey only himself and to remain as free as before. Which in, his work the Social Contract is reduced to a single stipulation, namely, “the individual member alienates himself totally to the whole community together with all his rights”.[9] If individuals give themselves wholly to the community conditions will be the same for everyone and no one will be tempted to jeopardize this state of shared equality. The relationship therefore between the citizen and the government is one of mutual understanding which works together for the betterment of the state. The sovereign will not work against the citizen just as the citizen will not work against the state because to do so would be to stray from the social contract which has been established particularly to counter the impulse of human nature which is corrupted by civilization.[10]

Or such was Rousseau’s understanding. Hobbes’ understanding varied significantly as Hobbes maintained that absolute control over society belonged to the state and the role of the citizen within this model was to surrender their rights completely as all powers and laws are to be exercised by the sovereign. Hobbes presents:

“that a man be willing, when others are so too, as far forth as for peace and defence of himself he shall think it necessary, to lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men as he would allow other men against himself”.[11]

The purpose of this societal agreement is, similar to Rousseau’s theory, for the betterment of the community as Hobbes believes that without absolute government control society will descend into its natural state of perpetual warfare. On board with Hobbes’ in part, was Jean Domat who perfected the absolutist model in relation to French government in the late seventeenth century. According to Domat, the role of the governed was to unhesitatingly obey the monarch as such obedience was on par with subservience to God. The role of the sovereign’s royal absolutism should “reflect the operation of the will of God” and the law of the Church.[12] Different again, is Locke’s theory regarding the social contract which features the individual surrendering of some natural rights in exchange for the collective protection of a communities property and public good. Unique to Locke’s model is the idea that society may rebel against the installed government, should that government prove corrupt or fail to act on behalf of society, where Hobbes’ model finds no justification for such actions and Rousseau’s model presents a scenario where the balance of power is inevitably perfect and no individual would move to compromise the rights of the whole as such an action would also compromise his freedoms on an individual level within the state.[13] Similar to the previous discussions therefore, though enlightened thinkers presented models for ‘perfected’ social contracts, they effectively demonstrate the subjective nature of the human capacity for reason.

The enlightenment is a unique and identifiable period because it represents a vocalization of some of the social commentaries and criticisms which were harbored in Europe after a drawn out period of corruption within the government and the Church. To this extent, enlightened thinkers demonstrate a conglomerate interest in identifying the failings within contemporary society and suggesting methods for their improvement. Nevertheless, enlightened thinkers demonstrate a plethora of understandings regarding human nature and its functioning’s which cannot be presented as representing any one amalgamated belief system.

Works Cited

Domat, Jean. "On Social Order and Absolute Monarchy." Oeuvres completes, nouvelle edition

revue corrigée. 3. (1829): pp. 1-2, 15-2 1, 26-27, 35, 39, 40, 44-45. http://www.fordham.edu/ halsall/mod/1687domat.html

Robinson J.H. ed., Readings in European History 2 vols. (Boston: Ginn, 1906), Vol. 2, pp. 273-

277.

Kant, Immanuel. "What is Enlightenment?." Modern History Sourcebook. (1784).

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/kant-whatis.html.

Hobbes, Thomas. "Leviathan." Modern History Sourcebook. . http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/m

od/hobbes-lev13.html.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Contrat social ou Principes du droit politique. Paris, 1800.

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/Rousseau-soccon.html.

Voltaire. Candide. Boston: St. Martin's, 1999.

[1] Immanuel Kant, "What is Enlightenment?," Modern History Sourcebook (1784), http://www.fo rdham.edu/halsall/mod/kant-whatis.html.

[2] J.H. Robinson, ed., Readings in European History 2 vols. (Boston: Ginn, 1906), Vol. 2, pp. 273-

277.

[3] J.H. Robinson, ed., Readings in European History 2 vols. (Boston: Ginn, 1906), Vol. 2, pp. 273-

277.

[4] Thomas Hobbes, "Leviathan," Modern History Sourcebook, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/m od/hobbes-lev13.html.

[5] Thomas Hobbes, "Leviathan," Modern History Sourcebook, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/m od/hobbes-lev13.html.

[6] Jean Jacques Rousseau, Contrat social ou Principes du droit politique, (Paris, 1800)http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/Rousseau-soccon.html, pp. 240-332.

[7] Jean Jacques Rousseau, Contrat social ou Principes du droit politique, (Paris, 1800)http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/Rousseau-soccon.html, pp. 240-332.

[8] Voltaire, Candide, (Boston: St. Martin's, 1999), Print.

[9] Jean Jacques Rousseau, Contrat social ou Principes du droit politique, (Paris, 1800)http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/Rousseau-soccon.html, pp. 240-332.

[10] Jean Jacques Rousseau, Contrat social ou Principes du droit politique, (Paris, 1800)http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/Rousseau-soccon.html, pp. 240-332.

[11] Thomas Hobbes, "Leviathan," Modern History Sourcebook, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/m od/hobbes-lev13.html.

[12] Jean Domat, "On Social Order and Absolute Monarchy," Oeuvres completes, nouvelle edition revue corrigée, 3 (1829): pp. 1-2, 15-2 1, 26-27, 35, 39, 40, 44-45, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1687domat.html (accessed ).