Emergence of Modern Middle East - Ottoman Empire and Egypt

Ottomas Empire History (Part 1)

The 18th and 19th centuries were not times of respite for the Ottoman rulers. They faced constant threats from expansionist European states that devised wicked schemes to split the empire. Within the empire, there was a rising tide for change due to many Ottoman loses in the Balkans, and financial problems exacerbated by European loans. Many notables proposed adopting European state patterns, technological inventions and cultural norms to strengthen the Empire and counter European power. Thus came the period of reform, or Tanzimat, where the Ottomans rulers initiated military, bureaucratic, judicial, societal and religious reforms. In the first chapter of his book Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, Akram Khater presents the primary documents which document these political reforms and local reactions to them. Implementing political reforms borrowed from Europe changed the previous relationship between the Ottoman and Egyptian governments and their subjects, and produced different reactions from the diverse populations that inhabited the empire.

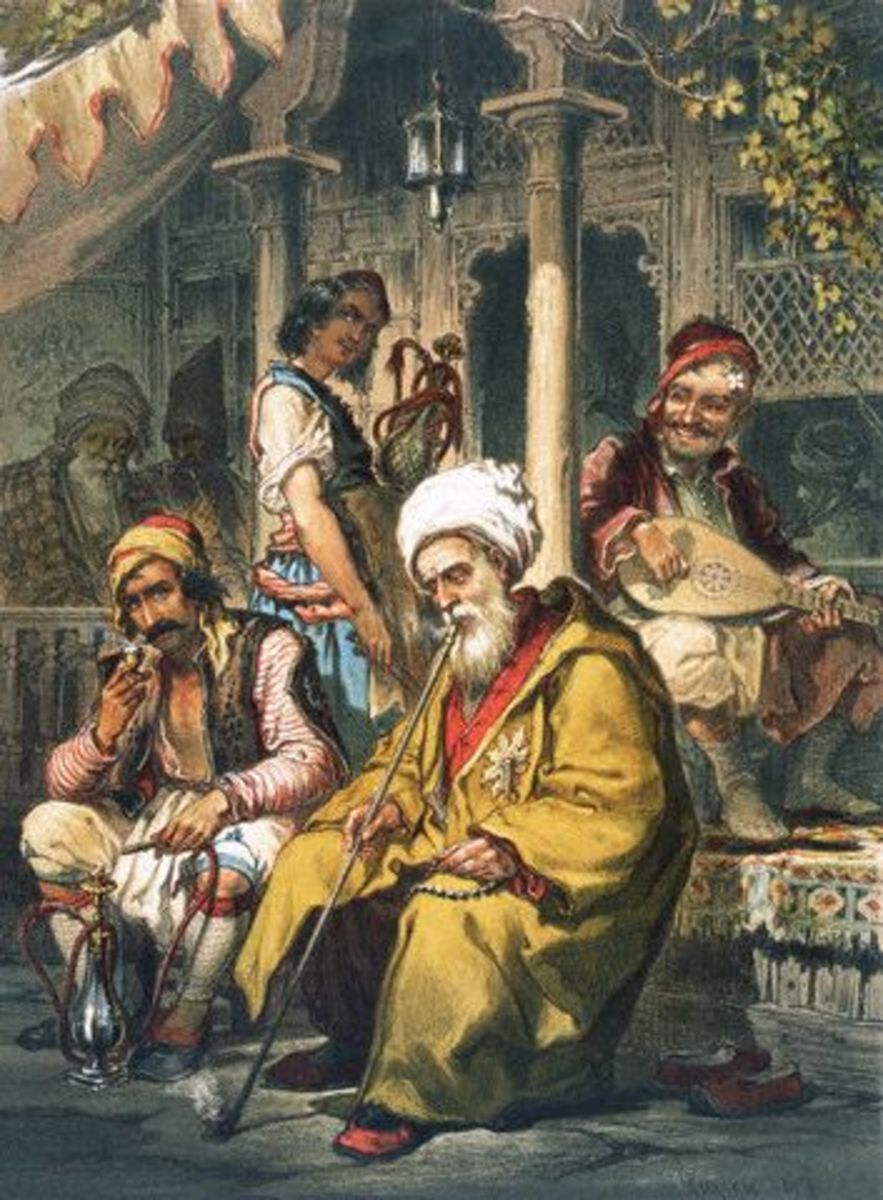

The Ottoman Empire was unique in its setup. It contained various ethnic groups such as the Slavs, Turks, Kurds, Jews, Egyptians and Arabs, and religious factions such as Greek Orthodox, Islam and Judaism. The Empire’s many ethnicities made governance very flexible and fluid. The fluidity permitted various ethnic and religious entities to coexist peacefully under the umbrella of the Ottoman Sultanate as long as no foreign powers threatened to split it. But once the Europeans made incursions, on the pretext of preserving their Christian subjects within the empire, it ran in to the danger of splitting apart. In the presence of unified and hostile powers, the diverse administrations and various governing parties in regions became a danger because of divide and conquer strategies used by the Europeans. Thus, the chief goal of the Ottoman reform agenda was to centralize administration and extend the government’s reach into the lives of its subjects to form a unified entity capable of withstanding European imperialism. The sources Khater has collected in chapter 1 of his book are useful because it “provides valuable clues as to how some Ottoman officials understood the goals of the Tanzimat” (11). In the third document, which is an Ottoman government decree issued to the Amir of Shamr the author contrasts the Bedouins and the urban folks. The decree basically expects the Amir to settle the wandering Bedouins, give them responsibilities such as land for cultivation and subsequently taxation, and make them beneficial citizens useful in science, arts and technology for the benefit of the empire. In the second document which is a decree by the Sultan reaffirming the privileges and immunities of non-Muslim communities in the empire, the Sultan seeks to do away with the divisive millet system and establish equality among Muslims and non-Muslims to unify them. The decree mentions the establishment of mixed courts which would not be partial towards Muslims. This decree also includes equal taxes, codification of laws, establishments of government owned enterprises to employ and serve the people. The first document, the Hatt-I-Serif, which initiated the Tanzimat, proclaimed the establishment of graduated taxation and citizen army instead of professional janissaries. This document also makes the Ottoman government’s firm decision to protect its subjects and assure security of property. These reforms brought a great change in the relationship between the State, society and the people. Whereas previously the Ottoman government let the people mind their own affairs, these decrees reveal a fundamental change the ruling parties expected to occur in people-government relationship. The first aspect of the change is the central government’s power and influence was increased so that it could serve its individual citizens directly without regional ethnic and religious mediators. The second aspect is making the people loyal to the central government by being conscious of the state’s needs and serving it with their talents, finances, education and good will. This wedlock of government and people would provide a direct interaction and strengthen it into a single entity, which Ottoman rulers hoped could not be splintered by European imperialists.

It is noteworthy to observe Egypt during the Tanzimat. Though Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire, it had tendencies to chart its own course towards reform. Mohammed Ali took Egypt in a new direction as he sought to establish his dynasty. His program for reform was industrialization of Egypt and expansion of territory in to Sudan; the former was never implemented and the latter brought much trouble up on the people. His son Ismail had grand ambitions of completely Europeanizing Egypt. Unlike the Ottomans who were more cautious in bringing political reform, Ismail wholeheartedly wanted to transplant Egypt from Africa to Europe. He allowed various European firms to have the upper hand in Egyptian industries. Ismail accumulated debt and doomed Egypt to infiltration by foreigners into important sectors in government. Muhammad Ali and his successors were power mongers; they did not seek to improve the conditions of the commoners, but sought to carve an empire at the cost of Egyptian labor. The results of Egyptian rulers’ reforms “brought economic hardship, social disruption, and political exploitation” (Cleveland 101). The Egyptian rulers were divorced from their people’s needs and attached to European charms. Thus, many awful results soured the relationship between the people and their government, and cultivated the seeds of nationalism.

In response to the intended changes by the Ottoman and Egyptian administrations, different people had diverse reactions based on the reform measures that affected them. The Ottoman Empire was by no means completely uniform, and though egalitarian decrees were issued, some ethnicities were more privileged than others. The intellectuals, Jews and Egyptians reacted differently to these changes because each ethnicity had a different relationship with the Ottoman government. The intellectuals like Jamal Al-Afghani and Mirza Malkum reacted favorably towards intentions that resembled progressivism between government and people. Though Khater’s 4th and 5th documents do not mention Al-Afghani’s and Malkum’s direct approval of the Ottoman decrees, nevertheless, their attitude towards western society’s scientific, philosophic and technological progression is favorable. Since the Ottoman government was trying to modernize, and the changes included a marriage of government and people for a hearty mutual benefit that would prevent European imperialism, which both disliked, it is reasonable to deduce they reacted to the changes favorably. The next group of people who reacted positively to the changes was the Baghdadi Jews as enumerated in Khater’s sixth document. Previously, as the document states, the Jews were oppressed in areas where Muslims were dominant. The progress from inequality to equality, and the promise of government assurance of property made the Jews and all such minority communities react positively to the Tanzimat. The next group of people whose reaction was not positive is the Egyptians. Egyptian reaction was in response to the reforms enacted by Muhammad Ali and his successors who operated independently from the Ottoman agenda. As mentioned above, Egyptian rulers’ agenda was to superficially Europeanize Egypt, not to solve the land troubles of the fellahin. Egyptian commoners suffered greatly because of the lack of concern of their rulers, who allowed foreign powers to exploit them. They took the Tanzimat as an era of western suppression, and rightly so because they were not partakers of the Ottoman agenda of supposed positive change, where minorities had more political and economic rights and opportunities. To Egyptians, more government intervention was the problem because their freedoms and opportunities were curtailed not increased.

In light of the external threat the Ottomans and Egyptians faced from European expansionists political reforms were inevitable. The reforms sought to transform the Ottoman Empire in to a new entity capable of standing against invaders. However, the reforms enacted by the government brought changes in relationship between the people and the state. The people were forced to give up their old identities and assume new ones, albeit for their own benefit. Those who were oppressed reacted positively, while those who were privileged became obstinate. In Egypt, the story turned out rightly negative because their autocratic rulers and foreign intervention. Though the reforms were never fully implemented in either state, it is remarkable to see the rulers leading their people into uncharted waters. Nevertheless, it is important to keep the crux of the matter to understand the rise and collapse of empires. At the heart of the matter is the delicate relationship between the governors and the governed.

Sources and Books

Ottoman Empire: World War I (Part 2)

Related Readings

- The Arab-Israeli Wars

The Israeli and Arab relations and their wars between 1967 and 1973 and how that is continuing to this day. This is a quick analysis of this time period. - Kurdistan and the Kurdish question in the Middle East

Look at the question of Kurdistan and the rights of the Kurdish people from the perspective of Yemen. Countries like Turkey, Syria and Iran fear that if they recognize the Kurds as an independent people then it will lead to more freedom movements - Origin of the Palestinians

The origin of the Palestinians and the land called Israel (or Palestine as called by Romans) and who should own the land. A brief history look at the modern day Palestinian-Israeli conflict.