A Just Jihadi

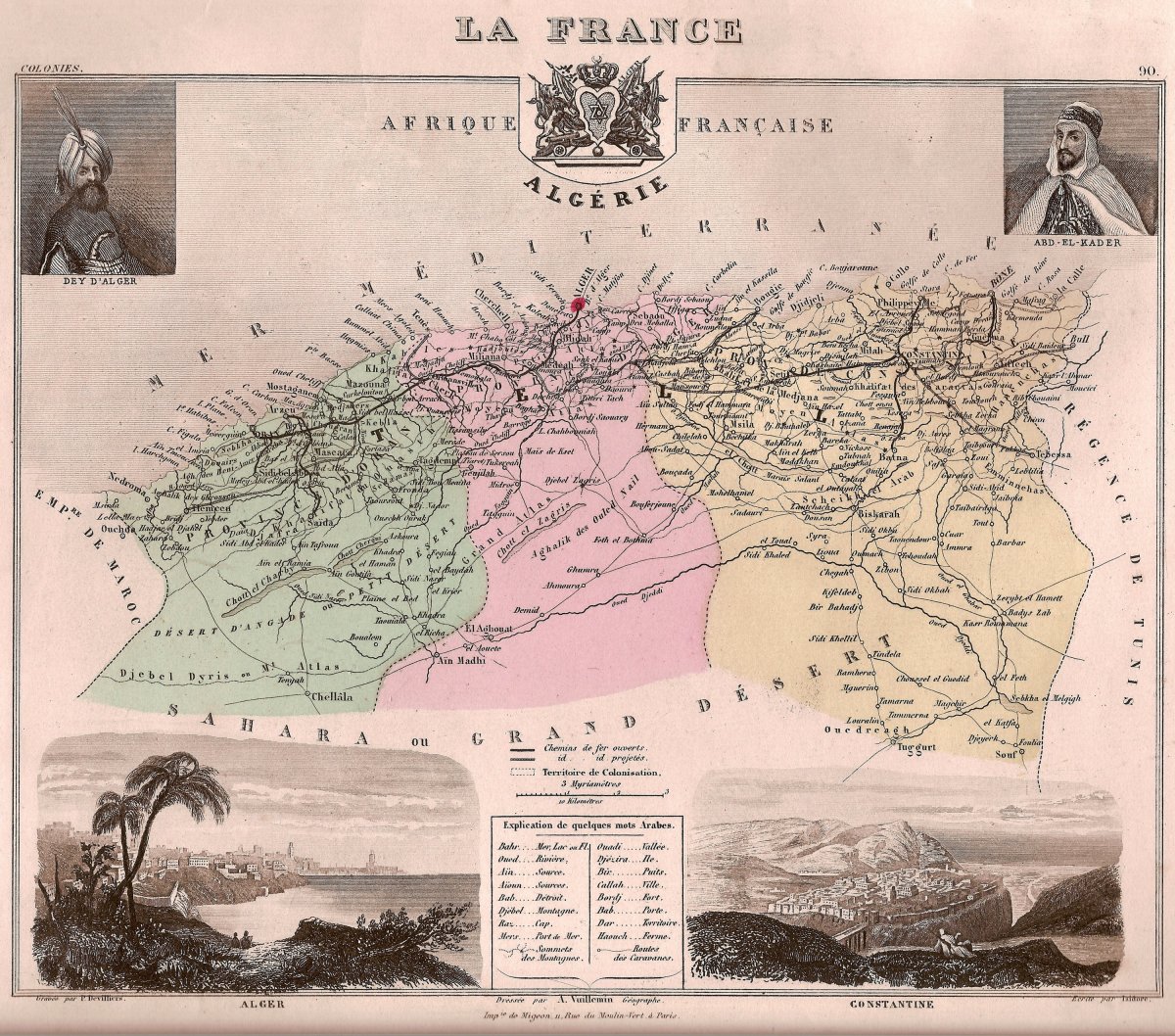

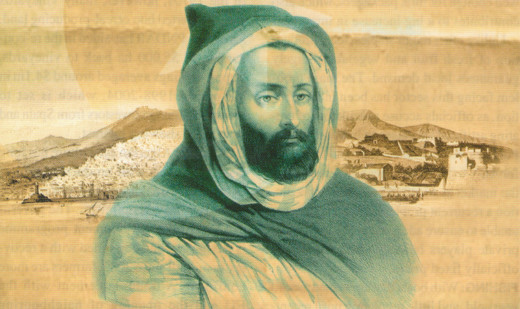

The first decades of French rule in Algeria were characterised by a long and bitter war waged between the European invaders, the Ottoman pashas and the local population. This bitter scene witnessed the emergence of a remarkable figure, the Emir Abd al-Qadir, son of Sheikh Mahiaddin, from the Hachem tribe near Mascara in western Algeria.

Al-Qadir's fame stems not just from the many years that he led the resistance against the French, but also from his natural sense of justice and honour. While it was his feats of arms that established his reputation, it was his conduct as both a fighter and a man of integrity that secured his place in history.

As Ottoman power waned in the 18th and 19th centuries, European powers, wanting to extend their influence across the Mediterranean, saw it as an opportunity for expansion. First, though, they would have to put an end to the reign of the "Barbary pirates", who were attacking European ships and damaging their conomies. In 1827, friction between France and Algeria over piracy climaxed when the dey of Algiers slapped the French consul's . face. The French used this to justify a blockade of the port of Algiers for the following three years.

King Charles X ordered the invasion of Algiers in 1830, partly to deflect attention from his growing unpopularity at home.

His choice was not fortuitous. In the early 19th century, Algeria was made up .of a loose confederation of tribes and communities ruled by Ottoman pashas.Using a plan originally devised by Napoleon Bonaparte, 34,000 French soldiers landed at Sidi Franj , near Algiers. Although the dey's troops put up a good fight, after three weeks the French had taken control of Algiers. The victory did not save Charles X, however. Within a few weeks he was deposed in the July Revolution and replaced by the Duke of Orleans, who went on to become King Louis Philippe.

The new king's government was less keen on the Algerian adventure, but strategic concerns mitigated against withdrawal. Britain had pledged to maintain the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire and might be tempted to increase their own influence in the area should France retire. The French therefore set about organising the defence of the city and settling the provincial hinterland but they ran up against strong resistance in the east from the bey of Constantine.

The bey reorganised the Ottoman administration by replacing Turkish officials with locals, making Arabic the official language and organising finances according to Islamic precepts. The bey successfully resisted the French for several years, spearheading a crushing victory over an expedition led by Bertrand Clauzel in 1836. Ultimately, though, his resistance was in vain. A year later, Constantine fell, ushering in the end of Ottoman rule.

The general disorder of the country and internecine rivalries between local rulers made the French invasion easy at first. But an organised opposition emerged in the west, centred around the figure of Abd al-Qadir.To understand how this young man emerged as the leader of the local tribes, it is necessary to look back for a moment.

Sheikh Mahiaddin was a holy man of great renown from the region of Muaskar, near Oran, a member of the Qadiri Sufi order. His popularity raised the suspicions of Hassan, the bey of Oran, and to avoid growing intrigue he decided to set off on the hajj , the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, in 1827. Sheikh Mahiaddin's journey with his son Abd al-Qadir involved two visits to the holy sites, as well as a sojourn to the court of Muhammad Ali, the Albanian viceroy of Egypt. It is said that the trip, had a great effect on the young Abd alQadir, who was impressed by Muhammad Ali's style of rule.

On his return, Sheikh Mahiaddin saw the vacuum left by his absence and the internecine rivalry between the tribes, but as he was a Sufi mystic, he tried to avoid political affairs. However, events prevented him from doing so. Hearing about the imminent arrival of French forces, Hassan Bey appealed to local leaders, especially Sheikh Mahiaddin, for help and refuge. At a meeting convened by the latter, most leaders concurred that they were obliged to give him asylum. But Abd al-Qadir disagreed, saying that giving asylum would be seen as an endorsement of the bey's crimes and lead to resentment from other Arabs in the region. The other leaders agreed with al-Qadir, and the French invasion of Oran in early 1831 saw the bey carted off to Alexandria.

The locals were now deprived of even the nominal protection of the bey, and appealed to the sultan of Fez, Abderrahman. The sultan sent a governor and troops to Tlemcen, on the border with present-day Morocco, but following French threats the governor was forced to withdraw.

Chaos now descended on the western region. The most important leaders came to Sheikh Mahiaddin and demanded that he lead them. He refused, arguing that he was too old to take up the fight. They insisted and began to menace him, blaming him for their plight. He said they needed someone younger and braver. It was that moment that they indicated their support for his younger son. Their choice was accepted, and to general acclaim, Abd alQadir was proclaimed emir al-muminin, or leader of the faithful, on November 2, 1832. He was 24 years old.

The new leader distinguished himself with his modesty from the start. "If I have accepted leadership, this is to have the right to be the first to march in the battles, and I am ready to step behind any other chief whom you judge more worthy and more capable than me to lead you, provided that he pledges to take in hand the cause of our faith."

Al-Qadir now represented the main hope for jihad against the French invaders.He was careful to refuse the title of sultan. Partly from religious conviction, partly from political nous — he did not want to alienate the sultan of Fez — he settled on the title of emir.

The new emir quickly set about gaining support from the people of the interior, tribal heads and religious communities. He led by example, shunning decoration and living austerely and devoutly. After some skirmishes with the French, he signed a treaty with the new governor of Oran, Desmichels, in 1834. This secured the French annexation of most of northern Algeria, leaving Abd al-Qadir with control over the area of Oran. Afterwards Oran was relatively peaceful, and al-Qadir began to consolidate his power there.

Al-Qadir's success led him to be called upon to provide support for the tribes further to the east. As his political power grew with the tribes, the French grew increasingly impatient, and given the ambiguity of the Desmichels Treaty, hostilities broke out once more. The arrival in Algiers , in 1836, of French General Bugeaud led to a new series of skirmishes and negotiations, at the conclusion of which a treaty was signed between the general and alQadir at Tafna in 1837.

Al-Qadir used the period of peace to unify the diverse tribes under his leadership and increase his military capabilities. When the French broke their treaty with al-Qadir, he gave the command to attack French strongholds and settlements. The emir was a natural-born military strategist and an expert horseman. His reputation allowed him to extend his authority such that by 1839 he controlled more than two-thirds of present day Algeria.

Al-Qadir set up a strong state, organised around the smala, his court, which traveled with him to avoid attack by the French. Taxes were levied and coins minted, public works were carried out, and education supported. Arsenals were built, producing not only rifles, shells and powder but also artillery guns.

The French general Bugeaud also used the period of respite to consolidate his strength. New French troops poured into the country. Bugeaud commenced a total and merciless war against the Algerians. His strategy was to starve the population by destroying its means of subsistence —crops, orchards, and herds. One by one, AlQadir 's strongholds fell and his leaders were captured. In 1842 the smala was captured, a big blow to the emir's resistance, although he is said to have felt the loss of his library most deeply.

A year later al-Qadir's state had effectively collapsed, and the emir sought refuge with the sultan of Fez. From the border regions he continued to conduct raids on French forces and exhort the locals to rise up once more. But the end was nigh. The French began to pressure the sultan to act against the emir. Fearing the 100,000 soldiers now effectively controlling most of Algeria, the sultan sent a force to expel alQadir. Caught in a pincer movement, the emir set off across the desert with the few hundred troops still loyal to him.

The escape plan did not last long. Near Kerbouz Hill, the Algerians noticed a force of French troops that cut off their route. Abd al-Qadir convened his leaders. Although they urged him to break through the troops to safety, he feared for the women and children traveling with his forces, and decided to surrender. The only question was to whom he should surrender. "My choice is made. I prefer to capitulate to the enemy whom I fought and on whom I inflicted much damage than to a Muslim that betrayed me."

The astonished General de Lamorciere, commander of Oran Province, received emissaries who told him the emir was ready to surrender, on the condition that his colleagues would not be harmed and that he would be given safe passage to either Acre or Alexandria in the Levant with his family and those of his followers who wished to accompany him. De Lamorciere accepted and Emir Abd al-Qadir gave himself up. It was December 1847.

The Duke of Aumal, son of King Louis-Philippe, was himself governor of Algiers when Abd al-Qadir surrendered. When they met briefly, the duke assured al-Qadir that the terms would be honoured. The emir and his retinue set sail for Toulon on Christmas Day. What they expected to be a brief stopover, however, ended in their imprisonment.

To be fair to the French, it was a messy business. For his first few weeks in Toulon, al-Qadir was assured that diplomatic parleys to receive him were being conducted with the pasha of Egypt. Meanwhile, back in Paris, the French were split between two groups. Some considered it France's duty to keep her promise. However, many parliamentarians still regarded Abd alQadir as a dangerous rogue and did not wish to see him escape to another Muslim land where he might stir up unrest again. In any case, Paris was in the grips of revolutionary sentiment, and the emir's plight took second stage to the Parisian barricades.

The king abdicated to general surprise in February. Subsequently, the civilian leaders of the Second Republic were singularly willful in ignoring Abd al-Qadir, who was left to rot in Toulon, then Pau, and finally at the Château d'Amboise in the Loire Valley in November 1848.

Despite the comfortable surroundings, the emir continued to live modestly, caring for his own and sending periodic entreaties to the deaf government, including to de Lamorciere, who was for some time minister of war. The emir insisted that his fight was over — that all he wished was to live the rest of his life in Muslim lands in peaceful contemplation. Even though he had himself promised Abd alQadir passage to the Levant, de Lamorciere ignored his pleas.

It was not until Louis Napoleon, who was soon to establish the Second Empire as Napoleon III, was elected president in December 1848 that things began to look up. Some of the first councils that he held concerned the prisoner, with two generals, including Bugeaud, in favour of his liberation. The minister of war opposed the motion, however. Over the next few years, political fights and a consolidation of power would distract the president from the emir's plight.

Liberation finally arrived in 1852, under dramatic circumstances. On October 16, Louis Napoleon arrived with a multitude of guards and flatterers and quietly entered the château. Abd al-Qadir was ushered in, and to his great surprise found the prince (who would in two months be proclaimed emperor) before him. Louis Napoleon announced that he was free, that he would be taken to Bursa in the Ottoman lands and receive a pension of 150,000 francs on the condition that he did not return to Algeria. Abd al-Qadir gathered his family together and they thanked Louis-Napoleon profusely.

After a brief visit to Paris the emir, notable for the acclamations he received wherever he went, set off for the Ottoman Empire. He was received with rather more circumspection by the Ottomans, however. The emir resided in Bursa for two years, where he was appreciated by scholars but barely tolerated by the local authorities. After a brief visit to France, Abd al-Qadir set off for Damascus, arriving there in 1855.

Abd al-Qadir then settled in Damascus, in what he hoped would be the last stop of his long journey. He was joined by a sizeable group of other North African exiles, but he reassured the local pasha that he was no longer interested in political intrigue, and retired to a life of prayer and scholarship.

Thus his retirement would have continued, had dramatic events not called upon his sense of justice to perform one last act of heroism. Religious animosities had been building in Syria since its occupation by Muhammad Ali in the 1830s, when he named a Greek Orthodox governor. Three decades later, the declaration of the Sublime Porte of the Hat-i Hiimayun put Christians on a more equal footing with their Muslim neighbours, which aggravated the people's resentment. To channel Muslim anger, local Ottoman officials instigated a pogrom against the Christians, which began on July 9, 1860.

When Abd al-Qadir heard of what was happening, he mobilised his followers and, forcing his way through the angry mob, went from neighbourhood to neighbourhood shouting, "Oh Christians, come to me! I am Abd al-Qadir the Maghrebi. Have confidence in me and come!" The Christians flocked to his group and found refuge in his house.

At one point his small band of followers had to confront a large mob demanding he open his doors. He refused, first beseeching them to come to reason, then threatening to rout them at which they finally dispersed.

An estimated 12,000 Christians were saved, including several consuls and the French consul himself. For this act of heroism he received France's Legion d'Honneur (some would say somewhat ironically), and other honours from Europe and the US.

Abd al-Qadir passed away in 1883. His remains were returned to his birthplace July 5, 1966, on the fourth anniversary of Algerian independence and the 136th anniversary of the French conquest, amidst much ceremony by the newly independent government.

A man of war, but also a just warrior, it is not for nothing that he is today considered Algeria's greatest hero. Nor is it a surprise that his standard, a combination of white for purity and green for Islam, was adopted by his countrymen as their national flag..,

© 2020 Farhi Lotfi