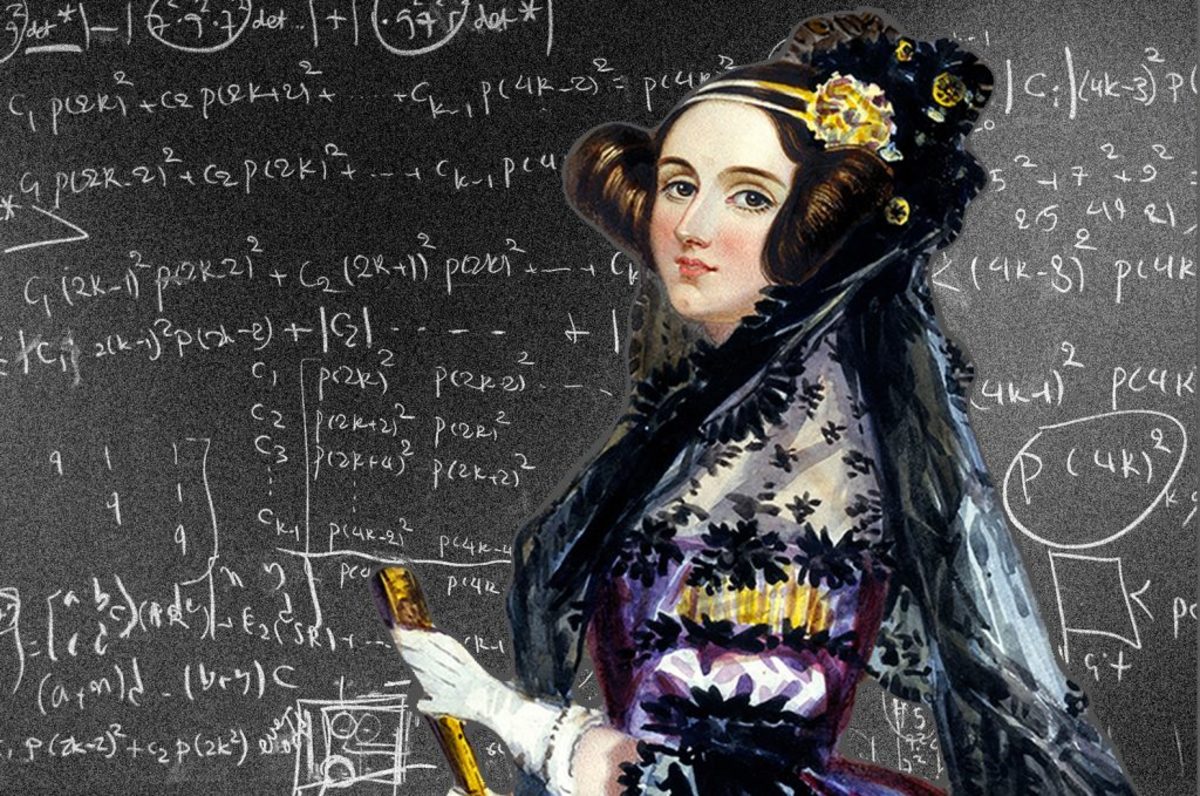

Enchantress of Numbers: Ada, Countess of Lovelace

Ada, Countess of Lovelace

![Margaret Sarah Carpenter [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Margaret Sarah Carpenter [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://usercontent2.hubstatic.com/8789847.jpg)

Who Says Girls Can't Do Math?

Ada didn’t exactly have a great start to life; born Augusta on December 10, 1815, her parents were no less than the poet George Gordon, Lord Byron and his wife Anne Isabella “Annabella”, Lady Byron. Lord Byron had been hoping for a son, and was extremely dismayed when Anne delivered a baby girl instead. He tried to show interest in the infant, nicknaming her “Ada,” but his relationship with her mother was abusive and, one month after Ada was born, Byron asked Anne to return home to her parents. Anne did so, taking her newborn daughter with her. Back then English law stated that the father had legal ownership over his children—meaning that if his wife divorced him because he was a sadistic S.O.B., he still got to keep the children—but Byron never made any attempt at claiming Ada. He signed a declaration of separation, asked his sister to keep an eye on Ada, and then took off for Greece, never to be seen in England—alive, at least—again.

Anne was beside herself with hatred for Byron, and that intense dislike carried over to her poor daughter. Leaving Ada in the care of her grandmother, Anne took off on her own, hobnobbing with high society, attending balls and symposiums. Anne did well to play the part of a concerned mother, frequently writing to her own mother as to inquire on little Ada’s health with explicit instructions to hang on to these endearing letters so she could use as proof against anyone who accused her of being an absent mother. At the same time, in some of her letters Anne referred to her own child as “it,” and in the few times that she spent with Ada she regaled the child with horror stories of her father and their friends. She refused to let Ada see a portrait of Byron until she was twenty years old, and Anne spent so much time badmouthing Byron and his alleged “insanity” that her sniping circle of friends used to trail Ada about, waiting for any sign that she had inherited her father’s insanity.

There is some debate now on what was affecting Byron mentally, but for Anne there was no doubt: poetry. His poetry drove his already fractured mind over the brink. Poetry in itself was bad in her opinion, too unstructured and wild with emotion, and Anne was convinced that had Byron invested himself in something more structured—like mathematics, which she adored—then he wouldn’t have gone so batty. Anne was determined not to have Ada fall into the same trap and made sure that the core of her schooling would be centered on mathematics.

Ada Lovelace by Alfred Edward Chalon

As a child, Ada was frequently ill, and a case of the measles left her paralyzed. Being bed bound made Ada yearn to fly, and one day she decided she was going to do just that—she was going to fly. Using her mathematical training, Ada designed a flying machine, heavily researched materials that would be suitable for flight, and spent so much time studying birds, their wings structures and proportions, that she wrote a book called Flyology. Her mathematical skills were remarkable for someone so incredibly young.

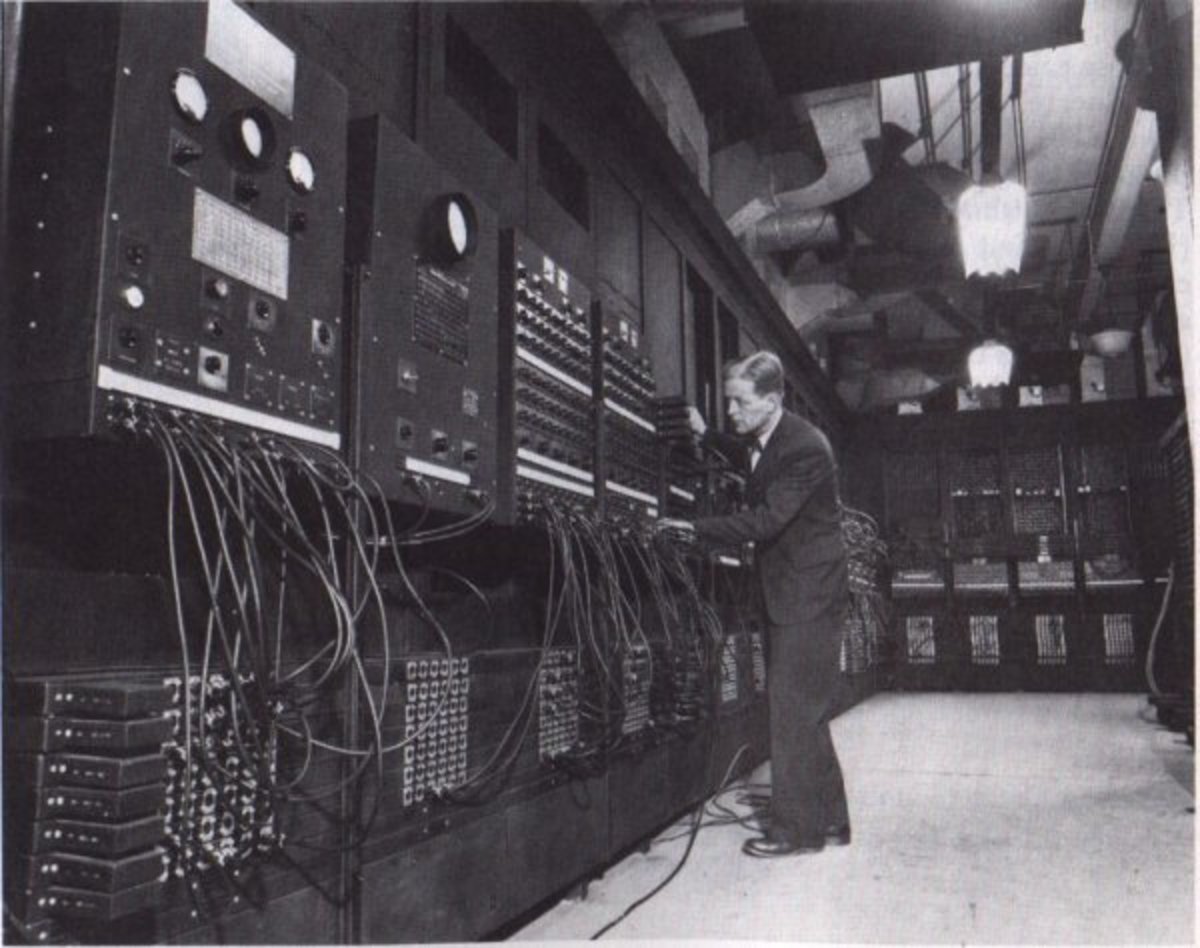

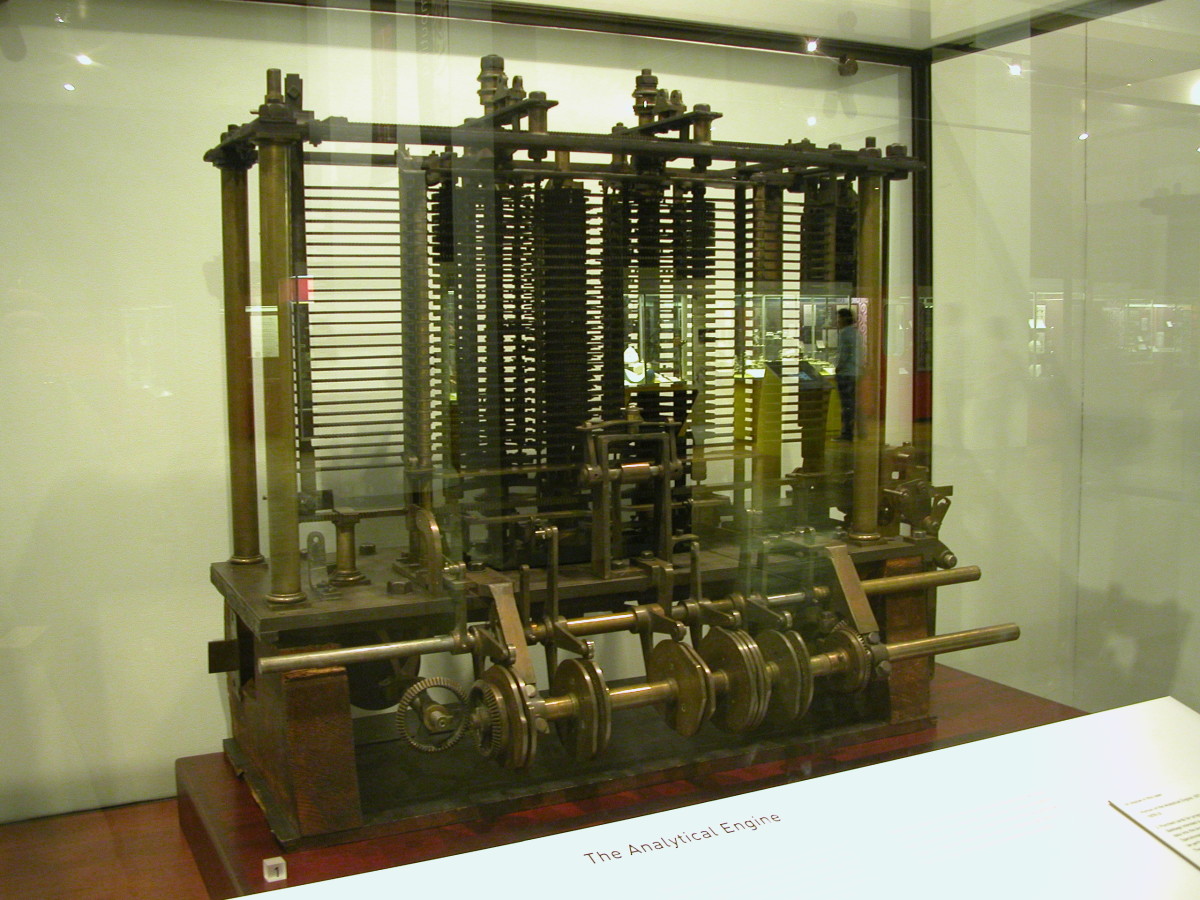

In 1833, Ada’s longtime tutor and friend, the female scientist Mary Someville, was so impressed with Ada’s ability in math that she was eager to introduce the now seventeen year old Ada to her friend, Professor Charles Babbage of Cambridge University. They met at a symposium where Babbage had unveiled his newest invention, a calculating machine he called The Difference Engine. Ada understood immediately how it worked, and her discussions of mathematical theories impressed Babbage so much that he invited her to become his assistant. Over time, Babbage was so thrilled by her abilities that he called Ada, “the Lady Fairy,” and “Enchantress of Numbers.” He encouraged her to publish her work, and while she did Ada only published under her initials, since it was considered improper for a woman to publish under her own name then.

In 1834, Ada married William King, the future Earl of Lovelace, and together they had three children. Becoming a wife, mother and countess in rapid succession didn’t keep Ada from her work with Babbage, especially since in 1834, Babbage designed his greatest creation yet; the Analytical Engine. While the Difference Engine was basically a complex calculator, the Analytical Engine was the forerunner to our modern computers, able to do many calculations at the same time.

Babbage had problems, however; his supporters in Parliament refused to contribute money to something when their first investment, the Difference Engine, was only half completed. With some effort, Babbage discovered that Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea was willing to research the Analytical Engine and publish his findings. Menabrea did so—in French. Ada spent nine months translating the mathematician’s articles and notes into English, eventually adding her own notes with it. In Note ‘G’, Ada designed a set of operations for solving particular mathematical problems … in other words, she designed the world’s first computer program. She even speculated that in the future the Analytical Engine could use math equations to do things such as play music!

Unfortunately, Ada didn’t live long enough to further research her beloved mathematical equations; on November 27, 1852, Ada, Countess of Lovelace, “the prophet of the computer age,” died from uterine cancer at the age of 37.

Ada Countess of Lovaelace works referenced:

Usborne Book of Famous Women, Phillippa Wingate et al 1997

"Ada Lovelace," http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ada_Lovelace

"Charles Babbage," http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Babbage#Analytical_Engine

"Mary Someville," http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Somerville

"Ada Byron, Countess of Lovelace," http://www.sdsc.edu/ScienceWomen/lovelace.html

"The Babbage Engine: Ada Lovelace," http://www.computerhistory.org/babbage/adalovelace/