England Invaded (7): Checkmate

By Nils Visser

Every historical yarn should have a large set-piece battle as a climactic ending, preferably one where everybody has everything riding on the outcome, not the loss of a castle and subsequent control of a valley somewhere, but total victory or defeat. Unfortunately, history is seldom kind enough to supply such a dramatic apex. However, it’s been said before, the First Baron’s War is very kind for anyone attempting to apply a storytelling narrative to it, and as such, provides that final epic confrontation that allows us to end this tale in style.

By a further stroke of luck, the various chroniclers who have thus far supplied us with our information, including Roger of Wendover, Matthew Paris, the chronicler who relied on John de Erly’s accounts for L'Histoire de Guillaume le Marechal, the unknown French author of Histoire des Ducs de Normandie et des Rois d'Angleterre , the chaplain of King Philip Augustus of France and up to a certain extent Raphael Holinshed, all cover the final stage of the war.

In the case of Mathhew Paris we know that he was personally acquainted with Hubert de Burgh, formidable Castellan of Dover Castle, and from his detailed descriptions it’s reasonable to assume he spoke to de Burgh about the battle. John de Erly was squire to the William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke and Regent of England. Although John de Erly stayed ashore at Sandwich, he witnessed the battle. The French author of Histoire des Ducs de Normandie has included so many accurate depictions and remarkable details that it is generally assumed he was attached to Louis’ expedition force. As such he wouldn’t have witnessed the battle, Louis was in London, but he will have heard first-hand accounts. All of these excellent writers have ensured that this is quite a well-documented battle, for which I’m very grateful.

The situation was such that it was pretty desperate for both sides.The considerable defeat at the Battle of Lincoln Fair meant that Louis had abandoned the second siege of Dover in order to look after his affairs in London which he could not afford to lose. The French prince’s judgement in this was correct, because a siege of London was exactly what William Marhsal was contemplating. Louis desperately needed reinforcements to replace the men lost at Lincoln and to shore up his forces which had so far relied on the English rebels to make up the numbers, however their commitment to his cause was fading and many had been captured at Lincoln. Louis was also in urgent need of new supplies and monetary funds.

Philip Augustus, king of France, was trying to ensure he wouldn’t fall afoul of the Pope who opposed the French expedition to England, so Philip couldn’t openly support his son, but did allow his daughter-in-law, Blanche de Castille, surreptious access to the French royal treasury. As Wendover explains: “Since the King feared to bear aid to his excommunicate son, having often been censured by the Pope for complicit with him, he imposed the whole of the work upon the wife of Louis.” Blanche de Castille wasn’t work shy, according to de Erly she: “ransacked France for assistance in men and money. She went at her task so energetically that if all those she assembled had come in arms to London, they would have conquered the whole kingdom.” Some of the rather grand names on the muster roll -among them sir Robert de Courtenay, sir Raoul de la Tournelle and Guillaume des Barres- are a further indication that the king of France didn’t oppose the reinforcement of Louis, it’s somewhat doubtful that these barons would have risked the ire of their king.

William Marshal, although undoubtedly delighted with the triumph at the Battle of Lincoln Fair, knew better than to confuse a single success with overal victory. De Erly puts it as follows: “The marshal was in a quandary. The king was young and penniless. The majority of the great men had sided with Louis. As a last straw, the greatest barons of France were coming to conquer the land.” Basically, Marshal couldn’t afford to let Louis unite with the army of thousands of Frenchmen that was about to cross the channel, and he decided to focus his efforts on stopping them at sea.

Marshal can be credited with a bit of foresight here, for he had already taken steps in January 1217 to protect the south-eastern coast when he appointed Philip d’Aubigné as the overall commander of royalist forces in an area that encompassed Kent, Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire, with specific mention of the Weald (Willikin´s playground) and the Cinque Ports.

There had already been a number of naval encounters. During the Second Siege of Dover, 40 French ships had approached the port, but had been driven back by a storm. A few days later they made a second attempt but that time Philip d’Aubigné and Nicholas Haringos brought a fleet of some 80 ships from Romney, including 20 ships specifically equipped for fighting, the remnants of the fleet King John had built. The French ships, much smaller on the whole, tried to make their way back to Calais, but many were brought to a standstill and forced to fight. A total of eight were captured by the English. The English stayed to blockade Dover and prevent reinforcements and supplies reaching Louis by means of this port.

By the by, the actual job description of ´Captain´ requires a brief comment. Contrary to today´s interpretation, a Medieval naval Captain often knew little about sailing, ships were a fighting platform and he, a knight of rank, was in charge of the ship´s complement of fighting men. It was the Master who actually sailed the ship, thus, when mention is made of `Philip d’Aubigné and Nicholas Haringos`, one may assume the first to be the Captain, and the second the Master.

Not much later, a few days after Louis heard of the disastrous outcome of the Battle of Lincoln Fair, quite a large fleet of some 120 sails was seen approaching Dover. The much smaller English fleet first sailed towards the French, and then changed course and sailed away to the south. The French gave chase, but when it appeared they couldn´t overtake the English, they turned back to Dover. At that point the English changed tack and attacked the rear of the French fleet, capturing a number of ships in the process.

However, when Marshal received word in August that Blanche de Castille was equipping a huge fleet in Calais, he decided to travel to Kent himself. He arrived in Romney on August the 19th. There he spoke to the sailing men of the Cinque Ports, whom he needed to man the fleet that would try to stop the French. These mariners weren´t eager to oblige him, they had many complaints to make about King John, who had treated them as serfs and taken away trading rights which were theirs by tradition. Marshal promised to redress their complaints, allocating new trading franchises and alluding to compensation in the form of French ships and supplies that would be captured. In the end the mariners agreed to fight the French, and all and sundry made their way to the port of Sandwich. In the nick of time.

The French fleet left the port of Calais a few days after Marshal arrived at Romney. According to Wendover “The fleet had been entrusted to Eustace, to lead it under safe conduct to the city of London….they had a strong wind at their backs which drove them vigorously towards England.”

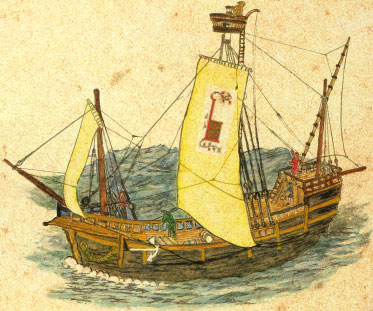

On the morning of the 24th of August the fleet was sighted before the Kentish coast. The first ship was the Bayonne. Sailing Master of the Bayonne was Eustace the Monk. Its Captain was Robert de Courtenay, seconded by Ralph de la Tourniele and also supported by the famous Guillaume des Barres the younger. There were thirty-three other knights on board as well, making 36 in total, quite a fighting complement. The Bayonne also carried “The treasure of the king,”, in all likelihood chest(s) of money for Louis, a trebuchet, war horses and of course the knight´s personal retainers (squires) and sailors. It was so deep in the water that the decks were almost awash.

The second great ship with knights sailed under the command of Mikius de Harnes, the third under the command of the Châtelain of Saint-Omer and the fourth under the command of the Mayor of Boulogne. Henry Lewin Cannon, who wrote a fine treatise on the battle, estimates that there were likely to be 100 to 125 knights on these four ships. Six other great ships, i.e. ships equipped for battle, carried men-at-arms. The rest of the fleet consisted of smaller vessels which carried supplies. There was probably a total of 80 ships.

The English fleet wasn´t led by William Marshal. According to John de Erly, Marshal was very keen on boarding his personal ship, a large cog, but was persuaded to stay ashore, his peers convinced him that England could not afford to lose its Regent at this stage. There was a reason for a pessimistic view, because the English were considerably outnumbered.

Hubert de Burgh had taken command of the English fleet, presumably his status as Justiciar meant that he outranked Philip d’Aubigné. According to Matthew Paris, de Burgh had sixteen war ships at his command, and 20 smaller boats. The Histoire des Ducs de Normandy names eighteen large ships and a number of smaller boats including galleys and fishing boats. Wendover quotes a total number of less than 40 ships. In Guillaume le Marechal there is mention of 22 ships, later it´s repeated that “Our people had only a few ships.”

De Burgh went aboard the leading war ship, joined there by Henry de Trubleville and Richard Suard, as well as other men-at-arms from Dover Castle and the best seamen from the Cinque Ports.

Another high-ranking commander was Richard Fitz-John, one of the bastard sons of King John. As he was the nephew to the earl of Warren, being the son of the earl´s sister who had been one of John´s mistresses, he had considerable status. In Guillaume le Marechal it is mentioned that “there went aboard with a fine troop Sir Richard the King’s son,” the said troops consisting of the earl of Warren´s retainers, as the earl “did not embark but fitted out a ship with knights and men-at-arms where his banners were.”

Similarly the earl of Salisbury had also fitted out a ship, though the most unusual was that furnished by William Marshal. This was a cog, a much bigger ship than most of the others of its day. As it wasn´t loaded it rode high in the water, which meant that the `castles´ on its high bow and stern provided a very formidable asset in the battle to come. The cog was crewed by men-at-arms in Marshal´s service, including Renaut Paien from Guernsey and Thebaut Blund.

According to Canon, the English, watching the enemy fleet approach, “were fully aware of the desperate nature of their enterprise and felt that little less than a miracle could enable them to stop the French fleet.”

D´Erly´s version of the story, in Guillaume le Marechal, was as follows: “They saw the enemy fleet advancing, in close line as for a set battle. Ahead sailed the ship of Eustace the Monk, who was in command. ”

As Marshal ordered his troops to take their stations aboard the English fleet, he told them: “remember that God has granted us on land a first victory over the French. And now here they are returning to England to take the kingdom from us. But God can help the good at sea as well as upon land and this time too he will help his own.”

The English waited until the French formation prepared to start clearing the isle of Thanet, and then struck out from Sandwich.

The French watched the English ships emerge from the harbour without a worry. “It’s only foot; there’s not a knight amongst them. They are ours. A happy chance has sent them to us: they won’t be able to resist us. They’ll pay our expenses. We’ll take them with us to London or else they will fish for flounders in the sea.”

Apparently Eustace the Monk advised caution, but he was overruled by de Courtenay. William le Breton, the chaplain of King Philip was to report: “while they were on the high sea they descried a few ships coming slowly from England: whereupon Robert de Courtenay caused the ship which he was in to be directed towards them, thinking it would be easy to capture them.”

The Bayonne sailed straight for the English ships, which were headed by Hubert de Burgh´s ship. At the last moment de Burgh´s ship veered away and bypassed the French column. The French on board the Bayonne, suspected cowardice and cheered and jeered as de Burgh passed. However, it´s been suggested that this was part of the plan. In the original positions, the French had the windward side, and as it was very early in the morning, the sun at their back, a considerable disadvantage for the English archers and crossbowmen. De Burgh, once on the windward side of the French column, sailed down the line and then, according to Paris: “found that they had gained the wind, tacked about with the wind now favourable to themselves, they rushed eagerly upon the enemy.”

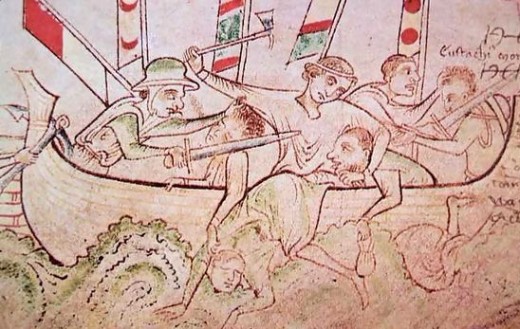

Richard Fitz-John, in the second ship, couldn´t follow de Burgh, he was too close to the Bayonne, and the two ships grappled. Anywhere from one to three other English ships now came at the Bayonne too, most important of which was William Marshal´s cog. At first the knights aboard the Bayonne, fought hard and prevented the English from boarding their ship. The rest of the French fleet continued sailing for London, not coming to the Bayonne´s aid, either because they had had no orders or because they didn´t perceive the danger. A danger which was real, as the English had a trick up their sleeve, if you look carefully at the Matthew Paris illustration of the attack on the Bayonne, you can see an archer shooting an arrow with a container of sorts and also someone using a staff sling to throw a container.

When the cog came alongside the Bayonne, it´s castles towered over the French deck, and from these heights the French were bombarded with, according to three contemporary sources, ground lime powder. When the containers smashed on the deck the powder enveloped the French and got into their eyes, effectively blinding them. The English followed this by a hail of arrows and quarrels from archers and crossbowmen, causing further distress on board of the Bayonne., according to Holinshed“themayne force to assaile the Frenchmen, and with helpe of their Crossebowes and archers at the first ioyning, made great slaughter of their enimies,”

Then the English men-at-arms boarded. According to de Erly, Renaut Paien jumped onto the French ship as one of the first, landing in the middle of the huddled French leadership, knocking them all over and taking Raoul de la Tournelle captive. He was quickly joined by Thebaut Blund and others and the French, unable to offer resistance, surrendered.

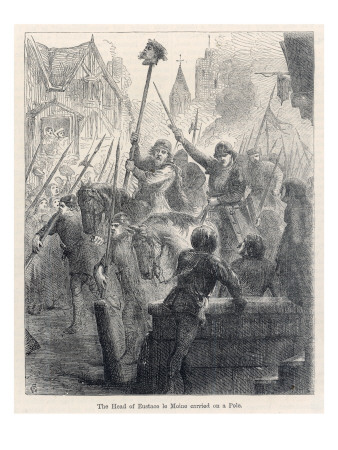

The victors quickly set about locating Eustace. According to Holinshed “a notable Pyrate, and hadde doone in his dayes muche mischiefe to the Englyshemenne.” Eustace the Monk was found by Richard Sorale and Wudecoc hiding in the hold. Eustace offered a large ransom in exchange for his life, but as he had served the English king before and then switched allegiance, the English were having none of it. In Guillame le Marechal we read that “There was one there named Stephen of Winchelsea, who recalled to him the hardships which he had caused them both upon land and sea and who gave him the choice of having his head cut off either upon the trebuchet or upon the rail of the ship. Then he cut off his head.”

Holinshed claims: “Enstace the Monke was founde amongest the captayns, who although he offred great summes of gold for his raunsom…... So that he myghte haue had his lyfe saued, & also to serue K. Henry, yet the English capitaynes would none of that, but Richard the basterd sonne of king Iohn….toke him, & cut off his head, and sent it vnto K. Henry his brother, as a witnesse of this their atchieued victorie.”

As the Romance of Eustace the Monk concludes, “Nor can one live long who is intent always upon doing evil.”

The seamen of the Cinque Ports bayed for further blood, but the rich and privileged will protect the rich and privileged, and the English knights formally took the French knights as prisoners. The French crew and other commoners of no notable birth were, as was the custom of the times, thrown overboard to drown at their own convenience. A total of 32 prisoners were taken.

After the Bayonne was taken, the battle rapidly became a route. The French fleet made their way back to Calais, pursued by the English. Most of the war ships, it’s said nine out of ten, made it back to Calais, presumably because the English concentrated on the softer targets, the 70 ships carrying goods and supplies instead of fighting men. All told, apparently only 15 ships made it back to Calais, meaning most of the cargo carrying vessels were destroyed or captured.

Wendover reports that some ships were rammed by the galleys. Others were grappled, their rigging cut so that the sails would fall atop the decks and disable the crews. Decks were cleared by arrow storms. Up to 4,000 men were said to have perished that day, killed in the fighting, captured and thrown overboard or choosing to jump overboard themselves.

We know that Hubert de Burgh captured two ships and that Richard Fitz-John had captured the Bayonne. Marshal was later to summon the whole navy of the Cinque Ports to London, including “that part lately won,” although that still doesn’t tell us how many ships were captured. Mention is made that many of the supplies were gratefully received by a war-torn nation, suggesting that more than just two supply ships were captured.

We do know the spoils were considerable. Holinshed wrote: “ The spoyle and praye of the Frenche shippes was verye ryche,A riche spoyle so that the Englishmen being loden wyth ryches and honour, vpon their safe returne home were receyued with great ioye and gladnesse.”

De Erly was bemused by the sailors parading the finery that must have come out of aristocratic baggage: “One ought to have seen, the next day, the sailors coming and going dressed in scarlet and silk, and outdoing one another in boasting. “

Marshal, keeping his promise to the Cinque Port Mariners, ordered the same spoils to be gathered together and divided equally amongst the sailors. He kept aside part of the funds to found the St. Bartholomew Hospital for the poor in Sandwich, the battle having been won on St. Bartholomew’s Day.

The victory was a decisive one. Even before the battle Louis had been short of supplies and the English now blocked his only supply route to France. His English allies had had enough. Louis asked Marshal for a parlay. This was arranged and it was eventually agreed that Louis would leave the country, with compensation money, and be absolved, i.e. have his excommunication reversed. He would also have to renounce all claims to the English throne, retracting those steps he had already taken towards official coronation. The treaty was signed by Louis on the 11th of September in Lambeth.

He got absolution near Kingston by the Pope’s legate, and was then escorted to Dover. Louis left England for the last time on the 28th of September 1217. The English who had sided with him were granted a pardon, and were allowed their lands back unless they had sold the land or traded it as ransom. They did have to cough up the compensation money that Louis was to receive.

The First Baron’s War was over.

Conclusions

A minor nobleman transformed into a guerrilla leader, hiding out in the greenwood with his stout yeomen wielding bows and arrows, outwitting French nobility, setting ambushes, partially involved in the defeat of an unpopular usurper king in order that the rightful king can claim his throne: Sound familiar? It would be foolish to claim that Willikin stood model for the iconic legend that is invoked by this description, there are far too many more likely candidates who either bear very similar names or are placed in more suitable geographic locations nearer to Nottingham and Sherwood Forest. However, if we ascribe to the view that our legendary icon is a symbolic accumulation for the deeds of many men, much like the Welsh affixed many popular tales to the name and title of King Arthur Pendragon, then Willikin’s actions may surely lay some claim to a percentage of the whole. For we may have nearly forgotten him, but in his own day he was likely to be a folk hero, long remembered around the hearth or campfires by English yeomen, proud and aware of the part they had played, still played and were yet to play in English history.

Time to conclude by offering answers to the questions posed at the beginning. We know now that there was no official King Louis I of England, because the second Treaty of Lambeth signed in 1217 saw Prince Louis renounce his claim to the throne, which also involved denying the fact that he had fulfilled, to all intents and purposes, the role of king for a brief period. How true the old adage that history is written by the victors. None-the-less, this still leaves the question as to why this period of English history has been more or less neglected in the collective historical awareness of those victors. After all, there had been very memorable heroes -not to forget two astonishing heroines (in as much as Blanche de Castille was a granddaughter of Henry I and Eleanor of Aquitaine and almost an English queen)- who had performed feats of incredible bravery, something usually much appreciated and celebrated in Anglo-Saxon culture.

The answer probably lies in the very complex political entanglements of the conflict. To begin with, in the fantastically simple but reasonably accurate historical terminology left to us by 1066 and all that, King John was a “bad king”. The barons who forced him to consider the Magna Carta, might be considered “naughty” in that they rebelled against their lawful king, but on the whole this is considered a “good thing” because the Magna Carta (now quoting directly from 1066 and all that) “was therefore the chief cause of Democracy in England, and thus a Good Thing for everyone (except the Common People).

There you have it, it is fitting that these Barons are seen in a favourable light, even though they were mainly interested in protecting the aristocracy from monarchs with tyrannical inclinations, not the common people.

However, real history has a knack of turning clear-cut good guys versus bad guys situations into murky confusion. King John was bad, and one reason this was so was that he employed foreign mercenaries, in fact, one of the demands made of John at the signing of the Magna Carta is that foreigners be removed from the country. A demand that was very popular amongst the populace, still xenophobic up to the extent that someone from Suffolk would consider a person from Norfolk as a foreigner, and anybody from Northumberland or Devon as positively exotic.

However, in order to oppose King John, the Barons invited over the French Dauphin and a French army, in other words, one set of foreigners replace another. A bit of moral high ground is lost there, or actually, this is more or less akin to treason, and in public relations treachery is usually not considered to be an endearing factor.

So we then have the `good ´ guys, i.e. the men who dared to opposed the tyranny of an unjust king, inviting over a Frenchman to offer him the throne. This works as long as they´re fighting King John, a tyrant. When John dies, however, and his young son Henry III is crowned, the new Regent, William Marshal, is canny enough to spin the politics in such a manner that it becomes far less acceptable to rebel against Henry III, too young to have caused anybody much offense. So suddenly the King´s supporters, quite possibly a bit too careful or cowardly in voicing opposition to King John and therefore not worthy of our approval before, have become the heroes, fighting a foreign oppressor in the name of the just king, whereas the former heroes, have turned sour, fighting for the foreign oppressor rather than against a tyrant.

Add to this Louis´s own failure to win hearts and minds by expressing disdain at the treachery of his English allies and appointing fellow Frenchmen to courtly positions, as well as the appalling decision to send Comte de Perche up north, where he invoked the resentment of the populace and lost a battle through gross ineptitude, and hindsight allows us to snigger at the Foolish French.

All the complex political spin aside, there is a clear cut story in there as well, and that is one of competence. Marshal rose to the status of Regent in the nick of time, his influence and wise decisions are apparent even without John de Erly´s attempts to laud him. Moreover, he found himself surrounded by the Right Stuff, i.e. men of exceptional bravery, prowess and capacity: Hubert de Burgh in defending Dover Castle and taking command of the fleet; Willikin of the Weald in demonstrating exceptional organizational skills and charisma in his orchestration of a guerilla war; and Philip d’Aubigné in bringing these two together in order to co-ordinate resistance in the south-east. Last-but-not-least the men of Sussex and Kent, who manned the ships that gave the English superiority at sea and who defended fortresses with their crossbows and took on knights with their longbows in the Greenwood.

As for the latter, it is interesting to note how many of the victories were influenced by massed archery long before English archery gained notoriety on French battlefields. King Henry III himself indirectly acknowledged the valuable role of the longbows in the Assize of Arms of 1252, which required all that "citizens, burgesses, free tenants, villeins and others from 15 to 60 years of age" should be armed, with a halberd or knife at the most, if they were very poor, but with a bow if they owned land worth more than £2. It is not inconceivable that he was thinking of the bows yielded by the men of the Weald, who used them to save his kingdom.

Louis would become King of France in 1223, but die of dysentery in 1226. His wife Blanche de Castille died in 1252, having been Regent of France twice before her death. Falkes de Breauté would spend a great number of years refusing to give back land which he had taken during the war. Eventually this led to the siege of Bedford Castle in 1224, mentioned in an earlier chapter. He died in exile in 1226. William Marshal died in 1219, Hubert de Burgh became de facto Regent of England, but managed to make enough political enemies to keep the remainder of his career ascending and descending on the wheel of fortune. The Warden of the Weald, Willikin, was paid a pension and made Sergeant of the Peace in 1241 (the predecessor of the current Provost Marshal of the Royal Military Police). He died in 1257, Holinshed’s final words on him a fitting epitath: "O Worthy man of English blood!"

Please Vote

Liked this? Please vote it up and leave behind a comment.Thanks.

CAN'T GET ENOUGH? A MORE DETAILED LOOK AT WILLIKIN OF THE WEALD HERE

- Stubborn Sussex: WILLIKIN OF THE WEALD

Stubborn Sussex is a series of articles exploring the motto 'Sussex wunt be druv' (Sussex will not be driven to do anything they don't like) in a historical context.