- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

Ephrata Cloister

William Penn (1644-1718) envisioned a diversified colony free of the shackles of European political and religious prejudices. His “Holy Experiment” became a laboratory where English Anglicans, Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, Welsh Quakers and French Huguenots were able to live together. It went so well that by the early 18th century immigrants from other areas, most notably Germany, began to flood into the colony. It wasn’t long until the colony was home to Reformed, Lutheran, Moravian, Schwenkfelder, Mennonite, Amish and German Baptist congregations.

Conrad Beissel

Beissel was born in March of 1691 in Eberbach am Neckar, Germany. His alcoholic father was a baker who died before Beissel’s birth and his mother died when he was only eight. He was raised by his older brothers and eventually he was apprenticed to a baker who also taught him how to play the violin.

As a young baker Beissel traveled throughout the region perfecting his skills. At the time Germany was almost 200 years post-Reformation and as Beissel traveled about, he became involved in Pietism, a movement to reform the state-supported Lutheran churches.

Beissel was meeting in small groups to read the bible and pray; however, these groups were not sanctioned by the church and the group members were found to be in conflict with the law. A conversion experience at the age of 27 led him to believe that celibacy was a prerequisite to holiness. Eventually Beissel’s religious beliefs caused him to be banished from Germany and in 1720 he immigrated to Boston and eventually moved on to Pennsylvania where William Penn offered freedom of conscience.

Conestoga Brethren Congregation

When Beissel came to Pennsylvania he settled in Germantown, just west of Philadelphia. In 1721 he organized a group of Seventh-Day Baptist monks into a colony in Lebanon County. Beissel’s sermons were more like tirades where he spoke in an almost trance-like state with his eyes closed and without referring to a bible. He claimed his revelations came directly from God. His attempt at a colony failed as his supporters slowly deserted him over the rigidity of his religious beliefs.

He then relocated to Conestoga, an area just east of present-day Lancaster and named by Penn for the Conestoga Indians, part of the Iroquoian nation that lived in the area. Once there he became a member of a Brethren group and was selected leader of the newly formed Conestoga Brethren Congregation in 1724.

Once again Beissel’s ideas had him at odds with some members of the congregation. His radical ideas as well as his promotion of celibacy led to a split within the congregation. Possibly due to his early life circumstances Beissel rejected the family unit as a natural institution. He also believed that the observance of a Saturday Sabbath separated the holy from the unholy and created a spirit of love and redemption. With the congregation turning against him, Beissel withdrew from the church.

Ephrata Cloister

In 1732 Beissel withdrew from Conestoga to northern Lancaster County to live the life of a hermit along the banks of the Cocalico Creek. Beissel always had the ability to attract followers and soon after his departure he was followed by those of a like-mind to his hermitage. At first it was mostly women and there was a great deal of turmoil created as wives left husbands to join Beissel and a life of celibacy.

What began as a small colony of devout individuals eventually became a thriving community of over 100 members supported by an estimated 200 family members by mid-century. Conrad Beissel was very much the center of the colony and he was directing the lives of Spiritual Virgins, Solitary Brethren and married couples pledged to celibacy based on his theology – a hybrid of pietism and mysticism. Beissel encouraged celibacy, Sabbath worship, Anabaptism, and the ascetic life but he also allowed families, limited industry and creative expression.

Beissel taught that all sex, even in marriage, was an abomination, an insult to God. Marriage was simply a means to procreate and avoid illicit sex. In order to secure salvation men and women must unite as celibate souls and live together only as friends. Only the Brethren and Sisters were seen as true believers but married couples, Householders, were allowed. Brethren and Sisters had to give up their worldly goods to the Cloister but Householders were allowed to maintain their farms and possessions.

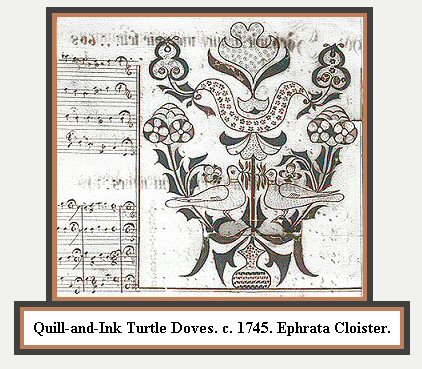

The community became known for its self-composed hymns, Germanic calligraphy and its complete publishing center which included a paper mill, printing office and bindery. Several prominent people joined the cloister: Conrad Weiser, a Lutheran elder, Peter Miller, a theologian and Frau Christopher Sauer, who deserted her printer husband to find peace on the banks of the Cocalico.

Way of Life

Ephrata is the Hebrew word for Bethlehem and Beissel was creating his utopia, a biblical city in the Pennsylvania wilderness. Ephrata Cloister was not only a prototype for later religious utopias; it was the first counterculture community in America. All of the structures were built according to specifications which can be found in the Scriptures: walls were one foot thick, no iron tools or nails were used, and door hinges were made of wood. Doorways were also very short and narrow so that everyone had to bow when entering a building or moving from room to room. In this way all were constantly reminded of their subservience to God and to maintain their path along the straight and narrow.

Although it would relax over time, at first life at Ephrata was stringently ascetic and monastic. Except for extremely special occasions they ate a vegetarian diet and drank only milk or water. There was only one meal served per day and they used wooden utensil and wooden plates. Males and females dressed identically: long, white Franciscan robes. They slept on wooden benches and used a block of wood as a pillow. They did not ride horses and had no use for either carts or plows.

They rose at 5:00 a.m. to begin their day of prayer and work. The day continued until midnight when they would meet as a group for two hours of worship, repentance, and communal contemplation. They would then rise at 5:00 a.m. to do it all again. At mealtime they listened to readings from the bible and every Friday night they were required to submit written descriptions of their spiritual state which Beissel would then read to the rest of the congregation on Saturday morning.

The commune produced an abundance of wheat, flax, and hemp and they had a viable vineyard. The Ephrata bakery was renowned in the area. They sold produce at local markets and as far away as Philadelphia and Wilmington. They operated two gristmills in addition to mills for linseed oil, paper and one for fulling cloth. The commune maintained a state-of-the-art printing facility that was one of the most important ones in the colonies. The Declaration of Independence was translated into seven languages and printed in Ephrata.

Contributions

The mystical poetry produced by the Ephrata Cloister was unsurpassed even by English writers. Its hand-decorated, illuminated manuscripts, or Frakturschriften, were masterpieces, exquisite expressions of spiritual devotion. The commune ran the largest printing and publishing operation this side of the Atlantic Ocean and produced the most important body of religious music in the colonies. Conrad Beissel wrote the first treatise on music in America.

Dissolution

With the death of Beissel in 1768 the society quickly declined. Beissel was succeeded by Peter Miller but it had been the charismatic personality of Beissel that had driven the commune to the successes it had achieved.

The monastic life no longer attracted followers and by 1813 the last of the celibate members died. The remaining members, the Householders, formed the German Seventh Day Baptist Church. Poorer members of the new congregation lived in the buildings of the commune and altered them to fit their needs.

By 1929 the remaining members of the congregation living at the Cloister disagreed with each other over the disposition of the site and its artifacts. In 1934 the courts revoked the original incorporation charter for the church and turned it over to a receiver. In 1941 the site, 28 acres and all buildings were sold to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Today the site is a National Historic Landmark administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

God's Acre