- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

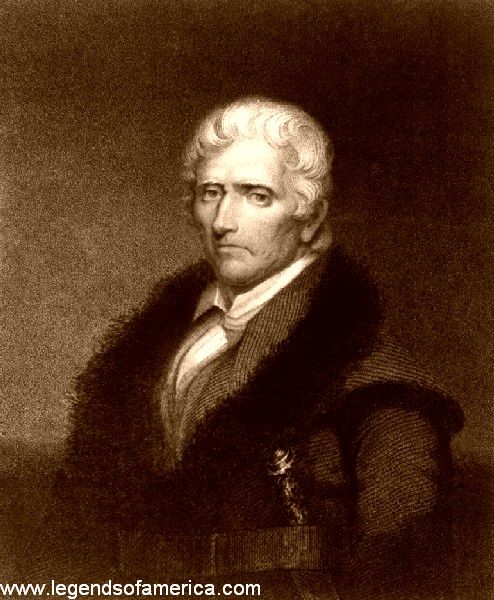

Essay on the Life of Daniel Boone

The Life of Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone is an American frontiersman, often considered to be the first of his kind, being the first to establish a settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains and living off the land there (Faragher, 350). He was the epitome of what Americans have come to think of as a pioneer and came a full century before the large expansions westward that most people associate with frontiersmen. Boone attained a level of fame within his own lifetime, his exploits being published throughout the United States and Europe. He was lofted to the status of American folk hero, and as such, many misconceptions about the actual events of his life exist.

Boone was born in Berks County, Pennsylvania near the city of Reading to Quaker parents, Squire and Sarah Boone who had emigrated from England. Boone was the sixth child of his family of eleven children and was raised in the Quaker tradition popular in Pennsylvania in the eighteenth century (Brown, 4). While considered to be eastern Pennsylvania by modern standards, Berks County was the edge of the American frontier in Boone’s childhood. He spent the first sixteen years of his life there, and it was where he learned the crafts of hunting and farming for survival. He also would have encountered members of the Lenape tribe, natives with whom the Quakers had good relations. He, in part, learned to hunt from members of the Lenape. It was at this time in his life that he supposedly shot a panther through the heart as it leapt at him, though this story cannot be verified and is widely considered to be a legend (Faragher, 9).

The remainder of Daniel Boone’s youth was spent in yet another frontier location of the time, Mocksville, North Carolina where his father moved the family in 1750. Boone received little formal education, spending his time and energy hunting to help provide for his family. Faragher explains that he learned to read and write on his own, often reading books on long hunting expeditions (55). This practice allowed him to become on par with most other literate men of his time.

Despite being raised in the pacifistic Quaker tradition, Boone volunteered to be apart of the Militia raised by British troops at the outset of the French and Indian War in 1754. He served as a wagoner alongside his cousin Daniel Morgan. Morgan would go on to become a United States general in the Revolutionary War, while Boone was destined to become the frontiersman known today. Boone was nearly killed in the Battle of Monongahela, sometimes referred to as Braddock’s Blunder after his general whom many people blamed for the attack. Regardless of whether or not the battle was a planned encounter that went poorly or an easily avoided ambush that the general marched right into, Boone was left with a poor opinion of the situation and complained about it for years after (Wallace, 17).

Boone returned home in 1756, long before the end of the war which lasted until 1763. There he married and started a family while living on his father’s property. This peace was short lived as the area was soon invaded by the Cherokee who had been allies of the British but were now in conflict with them. This forced the Boone’s to move out of their home, and caused Boone to return to militia life. He was known for his expeditions deep into Cherokee territory that took him beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains (Faragher, 62-63).

According to Faragher, these expeditions continued long after the fighting with the Cherokee had stopped, and Boone would go out on long hunting excursions for months at a time, collecting a large number of pelts and visiting locations westward that few white men had seen (66). It was during this time that Boone would mark trees and write in caves indicating that he had been there. For decades after, people would find messaged carved into trees that said things such as “D. Boon Cilled a. Bar on tree in the year 1760" meaning “D. Boone killed a bear…” Messages such as this could be found as far west as modern day Tennessee. A phenomenon of forgeries sprang up around these finds, and many fake Daniel Boone messages have been identified over the years, though many others have been authenticated (Faragher, 57-58).

During his time serving in the militia as a wagoner in the French and Indian War, Boone had met a man named John Finley who had worked for the trans-Appalachian fur trade. Stories Finley told Boone first planted the seeds of interest in Boone for exploration of the areas west of the Appalachian Mountains. Boone did not act on this interest until over a decade when he happened to meet Finley again who rekindled his desire for exploration. This spurred Boone along with his brother, Squire, to ventured west of the Appalachian Mountains into Kentucky on one of their long hunting trips in 1767 (Faragher, 69-74).

Boone returned in 1769 to engage in a two year hunting expedition and exploit the opportunity before him. The native tribes had recently signed a treaty ceding Kentucky to the British and as such, the land was fertile with wild game and safe to explore. Boone was however captured by a group of Shawnee who did not acknowledge the authority of the treaty and considered Boone to be a poacher. His furs were confiscated and he was set free and told not to come back. Boone however did continue to hunt and in 1773 attempted moved with his family and with a number of other British colonists to start the first British settlement in Kentucky (Faragher, 89-90).

Tragedy struck the Boone family when Daniel’s son, James, was killed along with a number of other men from the exploration party by a group of Delaware, Shawnee, and Cherokee who believed they needed to send a message to the European settlers. Among those killed was Henry Russell, the son of William Russell who was the de facto leader of the expedition. Devastated by this loss, Daniel Boone along with the other potential settlers in his party abandoned their attempt at settlement and returned to east of the Appalachian Mountains (Faragher, 96).

These events lead into Dunmore’s War, fought between the forces of Lord Dunmore, the British Governor of Virginia, and the Shawnee Indians of the Ohio River Valley. Boone returned to his duty as a militiaman and helped in the effort by going on long expeditions to warn people who had not heard yet of the conflict that they needed to evacuate, and he defended the westernmost British occupied territory from Shawnee forces along the Clinch River. His exploits during the war lead to his promotion to militia captain and gained him notoriety among his fellow colonists (Lofaro, 44-48).

Following the short lived conflict, Judge Richard Henderson hired Boone to lead an trailblazing effort across the Cumberland Gap in the Appalachian Mountains and into Kentucky. This effort lead to the development of the famous Wilderness Road, which contributed greatly to Boone’s renown and is a large part of why people still know of him today. In 1775, following this expedition and assisting in the founding of settlements west of the Appalachians, Boone moved his family to the new town which he

had founded and named Boonesborough (Faragher, 75-76).

Once the revolutionary war began shortly after the final battle of Dunmore’s War, the militia turned on Lord Dunmore and both British and American forces were too preoccupied to properly offer protection to the settlers beyond the Appalachians. Native Americans saw this as an opportunity to expel these settlers. Over the following year, Natives were able to drive out many European settlers through raids of towns and frequent attacks on hunting parties, until those remaining numbered in the hundreds. Boonesborough was one of the fortified settlements that was able to survive in this time, though it remained under constant attack. It was in this time period that some of the most well known actions of Daniel Boone’s life occurred (Faragher, 130).

First among his heroics was the rescue of his own daughter and several other young girls who were captured by a raiding party of Native Americans. Boone took a group of men and tracked the Shawnee party for two days before catching up to them. He managed to ambush them when they paused to have a meal, and safely rescued his daughter and the other girls. This was a very celebrated moment in his life and lead to the dramaticized account in James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans (Faragher, 331).

During this time period, the British enlisted the help of the Natives in fighting the American forces and both parties found a mutually beneficial ally in each other. This increased the violence among the settlements throughout Kentucky as Chief Blackfish became involved in the conflict. Blackfish’s forces managed to injure Boone at one point in the fighting by shooting him through the ankle. Eventually, Blackfish was able to capture Boone while he was on a dangerous trip outside the safety of Boonesborough. Due to Blackfish’s raids, supplies were running low and the settlement needed salt to preserve the meat they already had. This necessitated the trip outside the fortified town during which Boone was captured (Faragher, 155-59).

What followed was a harrowing several months in which Boone gained the trust of Blackfish but also had to make it seem like he had not switched sides and supported the British. According to Bakeless (167) many of Boone’s men who were with him in captivity thought that Boone was sincere in his apparent change of heart. Chief Blackfish was not cruel, and in fact it was his people’s way to find a place in their society for prisoners of war. Boone and many of his men were forced to pass trials and then were inducted into Shawnee families, Boone being given the name Sheltowee meaning “Big Turtle.” Furthermore, Blackfish was open to Boone’s request upon capture that Blackfish not attack Boonesborough until the spring, since the women and children would not survive the trek back to Virginia during the Winter. Blackfish agreed to this, which bought Boone time to come up with a plan. Because of these actions, however, many of Boone’s men questioned his loyalty.

Boone’s opportunity to prove himself came in June of the following year when he learned that Blackfish was indeed planning to return to Boonesborough and capture the town. According to Lofaro (100-105) Boone managed to escape and race across the 160 mile distance in a matter of five days, both on horseback and on foot after the horse could go no further. Boone lead a raid across the Ohio river of the Shawnee there before Blackfish’s reinforcements arrived. This came as a surprise to the Shawnee who were expecting to be the aggressors. When Blackfish did arrive, Boone successfully defended his town against his former captor in a ten day standoff eventually proving victorious.

After defending himself from accusations brought up in a court martial against him and indeed proving himself not only innocent, but deserving of a promotion, Boone moved his family back out to Kentucky. During his captivity, they had fled, assuming he was dead. In this way, Boone’s fame continued to grow in the area and he was elected to Virginia’s general assembly (Lofaro, 105-106).

The Revolutionary War eventually spilled into the Ohio River Valley and pulled Boone back into his role as a militiaman. During these conflicts Boone lost his brother, Ned, and his son, Israel. Boone was even himself captured en route to take his place in the Virginia legislature by the British forces lead by Banastre Tarleton but was later released on parole (Faragher, 207-210).

Following the war, Boone moved to Maysville Kentucky, where he took on the role of a local businessman, owning a tavern and working as a land investor. Boone continued his work in the Virginia general assembly. By the time of his 50th birthday, he gained national renown when a historian named John Filson published his work The Discovery, Settlement And present State of Kentucke, which detailed the exploits of Daniel Boone. Though he had adopted a role set within civilization as opposed to the frontier, he still engaged in conflicts as a member of the militia against Native tribes contesting for land. His role was more diplomatic than in his early life and he actually helped negotiate peace between the two sides (Faragher, 235-37) This showed a changed in character from his younger self.

Boone found himself in financial trouble from his land speculating career. The market was too unpredictable and Boone held himself to a standard of ethics in business that precluded him from taking advantage of others, something which was deemed necessary to succeed as a land speculator. Faragher describes Boone as having “lacked the ruthless instincts that speculation demanded” (248). Escalating financial and legal trouble forced Boone to sell off his land and businesses and return to hunting. Eventually, he left Kentucky altogether.

Boone moved his family to Spanish Louisiana in what is now Missouri. This was technically an emigration as this region did not belong to the United States at the time. He was treated favorably by the spanish government and was appointed to the title of “syndic” in the area he lived, which gave him authority of a judge and a military commander, a responsibility in which he was said to behave in a fair and just manner (Faragher, 285-86). Following the Louisiana purchase in 1804, Boone lost his title of Syndic along with much of his land. Ten years later, the United States Congress listened to Boone’s petitions and granted him much of the land back, which he then sold to pay off his creditors (Faragher, 304).

The events near the end of Boone’s life are clouded by his legendary status. One account has him travelling as far west as the Yellowstone river, possibly at the age of seventy (Faragher, 295). Others claim he returned to Kentucky before his death to pay off the last of his creditors. According to Faragher (353), on September 26, 1820, Daniel Boone died at the age of 86 leaving behind a cultural legacy and archetype of the American Frontiersman.

Works Cited

Bakeless, John. Master of the Wilderness Daniel Boone. New York: Morrow, 1945. Print. Brown, Meredith Mason. Frontiersman: Daniel Boone and the Making of America. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2008. Print.

Faragher, John Mack. Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer.New York: Holt, 1992. Print. Wallace, Paul A. W. Daniel Boone in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg:Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1967. Print.

Lofaro, Michael A. Daniel Boone: An American Life. Lexington: University of Kentucky, 2003. Print.